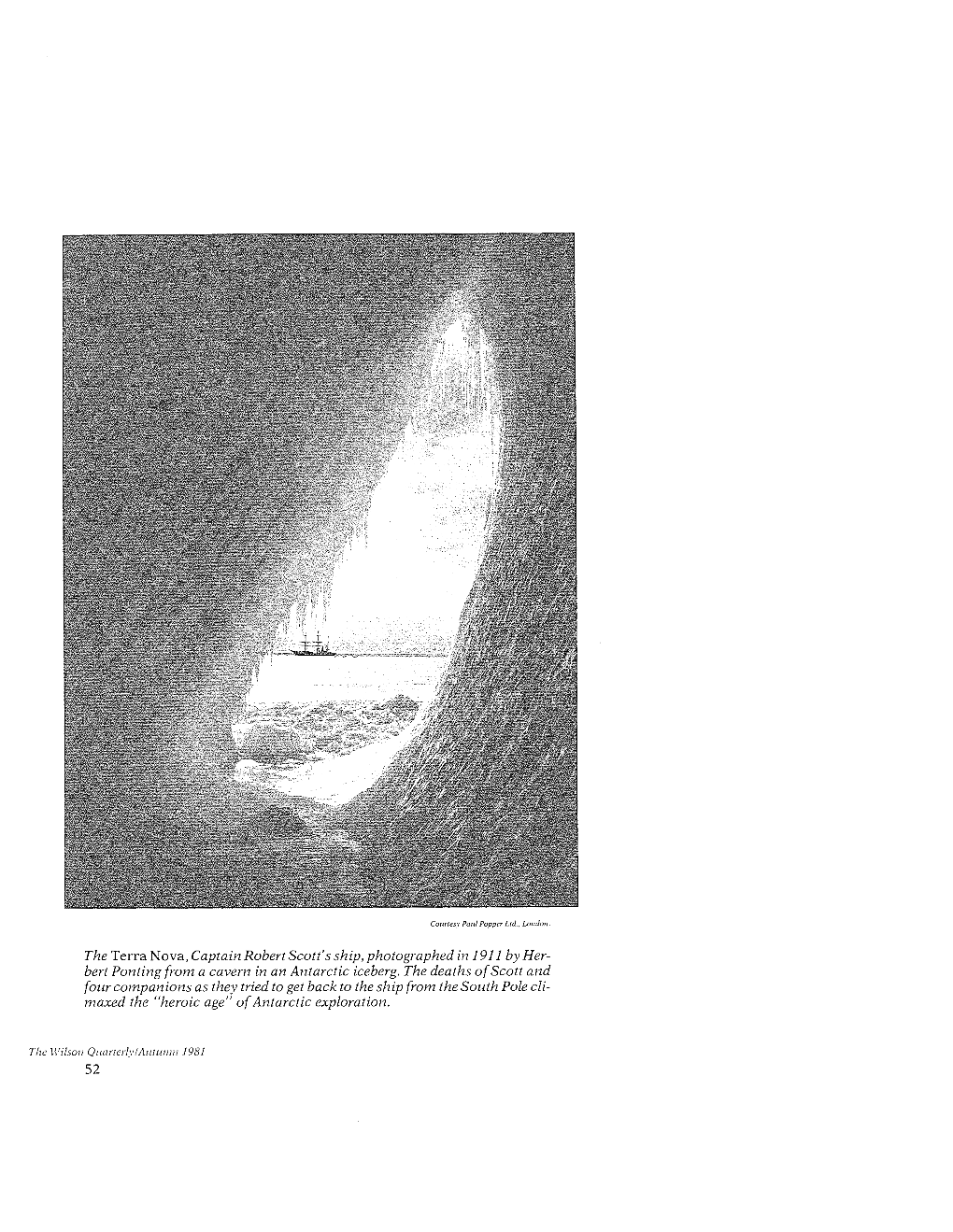

The Terra Nova, Captain Robert Scott's Ship, Photographed in 191 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map and Compass

UE CG 039-089 2018_UE CG 039-089 2018 2018-08-29 9:57 AM Page 56 MAP The north magnetic pole is not the same as the geographic North Pole, also known as AND COMPASS true north, which is the northern end of the axis around which the earth spins. In fact, the north magnetic pole currently lies Background Information approximately 800 mi (1300 km) south of the geographic North Pole, in northern A compass is an instrument that people use Canada. And because the north magnetic to find a direction in relation to the earth as pole migrates at 6.6 mi (10 km) per year, its a whole. The magnetic needle in the location is constantly changing. compass, which is the freely moving needle in the compass that has a red end, points The meridians of longitude on maps and north. More specifically, this needle points globes are based upon the geographic to the north magnetic pole, the northern North Pole rather than the north magnetic end of the earth’s magnetic field, which pole. This means that magnetic north, the can be imagined as lines of magnetism that direction that a compass indicates as north, leave the south magnetic pole, flow north is not the same direction as maps indicate around the earth, and then enter the north for north. Magnetic declination, the magnetic pole. difference in the angle between magnetic north and true north must, therefore, be Any magnetized object, an object with two taken into account when navigating with a oppositely charged ends, such as a magnet map and a compass. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Representations of Antarctic Exploration by Lesser Known Heroic Era Photographers

Filtering ‘ways of seeing’ through their lenses: representations of Antarctic exploration by lesser known Heroic Era photographers. Patricia Margaret Millar B.A. (1972), B.Ed. (Hons) (1999), Ph.D. (Ed.) (2005), B.Ant.Stud. (Hons) (2009) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science – Social Sciences. University of Tasmania 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date ii Abstract Photographers made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known photographers were the professionals, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of photographs were also taken on Belgian, German, Swedish, French, Norwegian and Japanese expeditions. These were taken by amateurs, sometimes designated official photographers, often scientists recording their research. Apart from a few Pole-reaching images from the Norwegian expedition, these lesser known expedition photographers and their work seldom feature in the scholarly literature on the Heroic Era, but they, too, have their importance. They played a vital role in the growing understanding and advancement of Antarctic science; they provided visual evidence of their nation’s determination to penetrate the polar unknown; and they played a formative role in public perceptions of Antarctic geopolitics. -

German Exploration of the Polar World: a History, 1870–1940, by David T. Murphy

394 • REVIEWS the derived surnames are Scandinavian. Following each VARJOLA, P. 1990. The Etholén Collection: The ethnographic of these three divisions is a long list of names. In Madsen’s Alaskan collection of Adolf Etholén and his contemporaries in home, the women spoke English and Russian, and the men the National Museum of Finland. Helsinki: National Board of spoke English, various European languages, and some- Antiquities. times multiple Native languages, raising questions (espe- cially when combined with essays by Jeff Leer and Lydia Karen Wood Workman Black) about multilingualism in the past. In what situa- 3310 East 41st Avenue tions were which language(s) used, and by whom? Multi- Anchorage, Alaska, U.S.A. ple language use is a foreign concept to many Americans, 99508 and perhaps we pay too little attention to its possibilities. So many people are involved in this volume that no one person using it could know all of them. One deficit is that GERMAN EXPLORATION OF THE POLAR WORLD: the essays have only self-identification of the authors. A HISTORY, 1870–1940. By DAVID T. MURPHY. Lin- This is also and more expectably the case of the nine coln, Nebraska, and London: University of Nebraska Alutiiq Elders in the final chapter, although there is a Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8032-3205-5. xii + 273 p., maps, listing of Alutiiq Elders, their places of birth and present b&w illus., notes, bib., index. Hardbound. US$49.95; residences (xi–xii), and the three editors are given very UK£37.95. brief biographical sketches (p. 265). A list of contributors would have been helpful. -

JOURNAL Number Six

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Six Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton MARCH 2012 1 Shackleton and a friend (Oliver Locker Lampson) in Cromer, c.1910. Image courtesy of Cromer Museum. 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Six March 2012 The Centennial season has arrived. Having celebrated Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition, courtesy of the ‘Matrix Shackleton Centenary Expedition’, in 2008/9, we now turn our attention to the events of 1910/12. This was a period when 3 very extraordinary and ambitious men (Amundsen, Scott and Mawson) headed south, to a mixture of acclaim and tragedy. A little later (in 2014) we will be celebrating Sir Ernest’s ‘crowning glory’ –the Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition 1914/17. Shackleton failed in his main objective (to be the first to cross from one side of Antarctica to the other). He even failed to commence his land journey from the Weddell Sea coast to Ross Island. However, the rescue of his entire team from the ice and extreme cold (made possible by the remarkable voyage of the James Caird and the first crossing of South Georgia’s interior) was a remarkable feat and is the reason why most of us revere our polar hero and choose to be members of this Society. For all the alleged shenanigans between Scott and Shackleton, it would be a travesty if ‘Number Six’ failed to honour Captain Scott’s remarkable achievements - in particular, the important geographical and scientific work carried out on the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions (1901-3 and 1910-12 respectively). -

The Centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’S Enduring Scientific Legacy and Ongoing Presence There”

Debate on 18 October: Scott Expedition to Antarctica and Scientific Legacy This Library Note provides background reading for the debate to be held on Thursday, 18 October: “the centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’s enduring scientific legacy and ongoing presence there” The Note provides information on Antarctica’s geography and environment; provides a history of its exploration; outlines the international agreements that govern the territory; and summarises international scientific cooperation and the UK’s continuing role and presence. Ian Cruse 15 October 2012 LLN 2012/034 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1.1 Geophysics of Antarctica ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Environmental Concerns about the Antarctic ......................................................... 2 2.1 Britain’s Early Interest in the Antarctic .................................................................... 4 2.2 Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration ....................................................................... -

AQUILA BOOKS Specializing in Books and Ephemera Related to All Aspects of the Polar Regions

AQUILA BOOKS Specializing in Books and Ephemera Related to all Aspects of the Polar Regions Winter 2012 Presentation copy to Lord Northcliffe of The Limited Edition CATALOGUE 112 88 ‘The Heart of the Antarctic’ 12 26 44 49 42 43 Items on Front Cover 3 4 13 9 17 9 54 6 12 74 84 XX 72 70 21 24 8 7 7 25 29 48 48 48 37 63 59 76 49 50 81 7945 64 74 58 82 41 54 77 43 80 96 84 90 100 2 6 98 81 82 59 103 85 89 104 58 AQUILA BOOKS Box 75035, Cambrian Postal Outlet Calgary, AB T2K 6J8 Canada Cameron Treleaven, Proprietor A.B.A.C. / I.L.A.B., P.B.F.A., N.A.A.B., F.R.G.S. Hours: 10:30 – 5:30 MDT Monday-Saturday Dear Customers; Welcome to our first catalogue of 2012, the first catalogue in the last two years! We are hopefully on schedule to produce three catalogues this year with the next one mid May before the London Fairs and the last just before Christmas. We are building our e-mail list and hopefully we will be e-mailing the catalogues as well as by regular mail starting in 2013. If you wish to receive the catalogues by e-mail please make sure we have your correct e-mail address. Best regards, Cameron Phone: (403) 282-5832 Fax: (403) 289-0814 Email: [email protected] All Prices net in US Dollars. Accepted payment methods: by Credit Card (Visa or Master Card) and also by Cheque or Money Order, payable on a North American bank. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Articles in Air Collected on Formvar films and Imaged by Scanning Electron Microscope

Open Access Atmos. Meas. Tech., 6, 3459–3475, 2013 Atmospheric www.atmos-meas-tech.net/6/3459/2013/ doi:10.5194/amt-6-3459-2013 Measurement © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Techniques A method for sizing submicrometer particles in air collected on Formvar films and imaged by scanning electron microscope E. Hamacher-Barth1, K. Jansson2, and C. Leck1 1Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Materials and Environmental Chemistry, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden Correspondence to: E. Hamacher-Barth ([email protected]) Received: 21 May 2013 – Published in Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss.: 19 June 2013 Revised: 4 November 2013 – Accepted: 7 November 2013 – Published: 10 December 2013 Abstract. A method was developed to systematically inves- area north of 80◦ before the aerosol particles were collected tigate individual aerosol particles collected onto a polyvinyl at the position of the icebreaker and are thus an appropriate formal (Formvar)-coated copper grid with scanning electron measure to characterize transformation processes of ambient microscopy. At very mild conditions with a low accelerat- aerosol particles. ing voltage of 2 kV and Gentle Beam mode aerosol particles down to 20 nm in diameter can be observed. Subsequent pro- cessing of the images with digital image analysis provides size resolved and morphological information (elongation, 1 Introduction circularity) on the aerosol particle population. Polystyrene nanospheres in the expected size range of the ambient aerosol Aerosol particles are ubiquitous in the troposphere and have a particles (20–900 nm in diameter) were used to confirm the major influence on global climate and climate change (IPCC, accuracy of sizing and determination of morphological pa- 2007). -

Public Information Leaflet HISTORY.Indd

British Antarctic Survey History The United Kingdom has a long and distinguished record of scientific exploration in Antarctica. Before the creation of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), there were many surveying and scientific expeditions that laid the foundations for modern polar science. These ranged from Captain Cook’s naval voyages of the 18th century, to the famous expeditions led by Scott and Shackleton, to a secret wartime operation to secure British interests in Antarctica. Today, BAS is a world leader in polar science, maintaining the UK’s long history of Antarctic discovery and scientific endeavour. The early years Britain’s interests in Antarctica started with the first circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent by Captain James Cook during his voyage of 1772-75. Cook sailed his two ships, HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure, into the pack ice reaching as far as 71°10' south and crossing the Antarctic Circle for the first time. He discovered South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands although he did not set eyes on the Antarctic continent itself. His reports of fur seals led many sealers from Britain and the United States to head to the Antarctic to begin a long and unsustainable exploitation of the Southern Ocean. Image: Unloading cargo for the construction of ‘Base A’ on Goudier Island, Antarctic Peninsula (1944). During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, interest in Antarctica was largely focused on the exploitation of its surrounding waters by sealers and whalers. The discovery of the South Shetland Islands is attributed to Captain William Smith who was blown off course when sailing around Cape Horn in 1819. -

Antarctica: at the Heart of It All

4/8/2021 Antarctica: At the heart of it all Dr. Dan Morgan Associate Dean – College of Arts & Science Principal Senior Lecturer – Earth & Environmental Sciences Vanderbilt University Osher Lifelong Learning Institute Spring 2021 Webcams for Antarctic Stations III: “Golden Age” of Antarctic Exploration • State of the world • 1910s • 1900s • Shackleton (Nimrod) • Drygalski • Scott (Terra Nova) • Nordenskjold • Amundsen (Fram) • Bruce • Mawson • Charcot • Shackleton (Endurance) • Scott (Discovery) • Shackleton (Quest) 1 4/8/2021 Scurvy • Vitamin C deficiency • Ascorbic Acid • Makes collagen in body • Limits ability to absorb iron in blood • Low hemoglobin • Oxygen deficiency • Some animals can make own ascorbic acid, not higher primates International scientific efforts • International Polar Years • 1882-83 • 1932-33 • 1955-57 • 2007-09 2 4/8/2021 Erich von Drygalski (1865 – 1949) • Geographer and geophysicist • Led expeditions to Greenland 1891 and 1893 German National Antarctic Expedition (1901-04) • Gauss • Explore east Antarctica • Trapped in ice March 1902 – February 1903 • Hydrogen balloon flight • First evidence of larger glaciers • First ice dives to fix boat 3 4/8/2021 Dr. Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjold (1869 – 1928) • Geologist, geographer, professor • Patagonia, Alaska expeditions • Antarctic boat Swedish Antarctic Expedition: 1901-04 • Nordenskjold and 5 others to winter on Snow Hill Island, 1902 • Weather and magnetic observations • Antarctic goes north, maps, to return in summer (Dec. 1902 – Feb. 1903) 4 4/8/2021 Attempts to make it to Snow Hill Island: 1 • November and December, 1902 too much ice • December 1902: Three meant put ashore at hope bay, try to sledge across ice • Can’t make it, spend winter in rock hut 5 4/8/2021 Attempts to make it to Snow Hill Island: 2 • Antarctic stuck in ice, January 1903 • Crushed and sinks, Feb. -

Cruise Reports

INSTITUTE OF OCEANOGRAPHIC SCIENCES - CRUISE REPORTS To purchase copies of these reports please email [email protected] in the first instance Some reports available electronically CR1 ROBERTS, D.G. & EDEN, R.A. 1974 £6 DE "Vickers Voyager" and "Pisces III" June - July 1973. Submersible investigations of the geology and benthos of the Rockall Bank. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Cruise Report No.1, 22pp. & figs. CR2 LAUGHTON, A.S. 1973 £8 RRS "Discovery" Cruise 54, 29th June - 15th August 1973. GLORIA studies of the mid-Atlantic Ridge (FAMOUS area) and the Azores - Gibraltar plate boundary. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Cruise Report No.2, 26pp. & figs. CR3 CREASE, J. & CARTWRIGHT, D.E. 1973 £3 RRS "Shackleton" Cruise 6, August - September 1973. ICES overflow survey 1973. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Cruise Report No.3, 13pp. & figs. CR4 CARTWRIGHT, D.E. 1974 £6 RRS "Discovery" Cruises 56 and 58, 30th October - 7th November and 5th December- 15th December 1973. International comparison of tidal pressure sensors, North Bay of Biscay. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Cruise Report No.4, 12pp. CR5 STRIDE, A.H. 1974 £6 RRS "Discovery" Cruise 55, September - October 1973. Geological reconnaissance with GLORIA and air-gun in the eastern Mediterranean. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Cruise Report No.5, 18pp. CR6 RUSBY, J.S.M. 1974 £6 RRS "Discovery" Cruise 57, 10th November - 1st December 1973. Current meter mooring and deep sea tide gauge recovery and long range sonar experiments (GLORIA). Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Cruise Report No.6, 9pp. CR7 EWING, J.A. 1974 o/p RRS "John Murray" Cruise 9, 5 September - 25 September 1973.