Subnational Government, Enshrined in the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interregional Diversity of Social Capital in the Context of Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Polish Voivodeships

sustainability Article Interregional Diversity of Social Capital in the Context of Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Polish Voivodeships Katarzyna Pawlewicz 1 and Adam Pawlewicz 2,* 1 Department of Socio-Economic Geography, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, 10-720 Olsztyn, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Agrotechnology, Agricultural Production Management and Agribusiness, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, 10-719 Olsztyn, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 May 2020; Accepted: 8 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: The relationship between social capital and sustainable development challenges is of special importance. However, social capital is a complex phenomenon that is analyzed in different contexts and cannot be investigated with the use of a single variable. Social capital is difficult to define, which is why the selection of variables for measuring social capital can be problematic. The aim of this study was to analyze variations in social capital at the regional level. The study was conducted in Poland, and it covered all 16 Polish voivodeships (regions) where social capital was evaluated based on five measures: civic engagement in political and social life, degree of selfless behavior, sense of security and social confidence, formation of social structures, and the observance of social norms (external factors), and attitudes (internal factors) that foster desirable social interactions. The correlations between the above measures were also determined. Composite indicators of the analyzed measures were developed with the use of the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method. The results were used to rank Polish voivodeships and group them into three classes based on the corresponding values of the adopted measures. -

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE NOVEMBER 17, 2016 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jan Grabowski THE INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. Wrong Memory Codes? The Polish “Blue” Police and Collaboration in the Holocaust In 2016, seventy-one years after the end of World War II, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated a long list of “wrong memory codes” (błędne kody pamięci), or expressions that “falsify the role of Poland during World War II” and that are to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly—and not by chance—the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry includes for the most part expressions linked to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes,” which they aspire to expunge from historical narrative, one finds, among others: “Polish genocide,” “Polish war crimes,” “Polish mass murders,” “Polish internment camps,” “Polish work camps,” and—most important for the purposes of this text—“Polish participation in the Holocaust.” The issue of “wrong memory codes” will from time to time reappear in this study. -

A Case Study: the Surroundings of the Eastern Part of the Former Airport Runway Rakowice-Czyżyny in Cracow

Bulletin of Geography. Socio–economic Series No. 27 (2015): 81–93 BULLETIN OF GEOGRAPHY. SOCIO–ECONOMIC SERIES DE journal homepages: http://www.bulletinofgeography.umk.pl/ http://wydawnictwoumk.pl/czasopisma/index.php/BGSS/index http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/bog ISSN 1732–4254 quarterly G Mechanisms of densification of the city in the neoliberal economy - a case study: the surroundings of the eastern part of the former airport runway Rakowice-Czyżyny in Cracow Dominika Hołuj1, CDFM, Artur Hołuj2, CDMR Cracow University of Economics, Rakowicka 27, 31-510 Kraków, Poland; 1Department of Economic and Social History, UNES- CO Chair for Heritage and Urban Studies; phone: +48 122 937 466; e-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author); 2De- partment of Regional Economy, Chair for Economy of Region and Spatial Engineering; phone: +48 122 935 314; e-mail: holuja@ uek.krakow.pl How to cite: Hołuj, D. and Hołuj, A., 2015: Mechanisms of densification of the city in the neoliberal economy - a case study: the surroundings of the eastern part of the former airport runway Rakowice-Czyżyny in Cracow. In: Szymańska, D. and Rogatka, K. editors, Bulle- tin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, No. 27, Toruń: Nicolaus Copernicus University, pp. 81–93. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ bog-2015-0006 Abstract. The article is a case study of land use planning in the surroundings of Article details: the eastern side of the runway of the former airport Rakowice-Czyżyny in Cra- Received: 5 December 2013 cow. The area was chosen because it is an example reflecting the history of many Revised: 22 April 2014 urban spaces that are well connected externally, well equipped in infrastructure, Accepted: 7 December 2014 and favourably located in the city. -

Financial Resources of Agricultural Manufacturers in Ukraine – Historical Experience and Its Modern Role in Enterprise Management

Education Excellence and Innovation Management: A 2025 Vision to Sustain Economic Development during Global Challenges Financial Resources of Agricultural Manufacturers in Ukraine – Historical Experience and Its Modern Role in Enterprise Management Oksana KRASNIKOVA, Poltava State Agrarian Academy, Poltava, Ukraine, [email protected] Iryna BORYSOVA, Poltava State Agrarian Academy, Poltava, Ukraine, [email protected] Antonina KALINICHENKO, University of Opole, Opole, Poland, [email protected] Anna BRZOZOWSKA, Czestochowa University of Technology, Czestochowa, Poland, [email protected] Abstract The use of historical experience is an important component of the modern economy reforming in Ukraine. The reforms of the second half of the 19 th to early 20 th century are of particular importance. As their immediate result was the creation of an extensive credit system for agricultural producers, which was very effective at that time. The article describes the main types of financial resources used by agricultural producers in Ukraine at the turn of the 19 th and 20 th century. The analysis of statistical data confirms the idea of the extraordinary vitality of small family-owned agricultural enterprises. In such places there has always been the possibility of replenishing a modest budget through both economic activity and handicraft industries, as well as loans of different origins. The use of historical experience can be extremely useful for increasing the competitiveness in both domestic and foreign markets. Keywords : Agricultural Sector, Agricultural Goods Producers, Budget, Financial Resources. Introduction The era of deep and comprehensive economic reforms in Russia, the beginning of which goes back to the period of the abolition of serfdom in 1861 is of considerable public interest. -

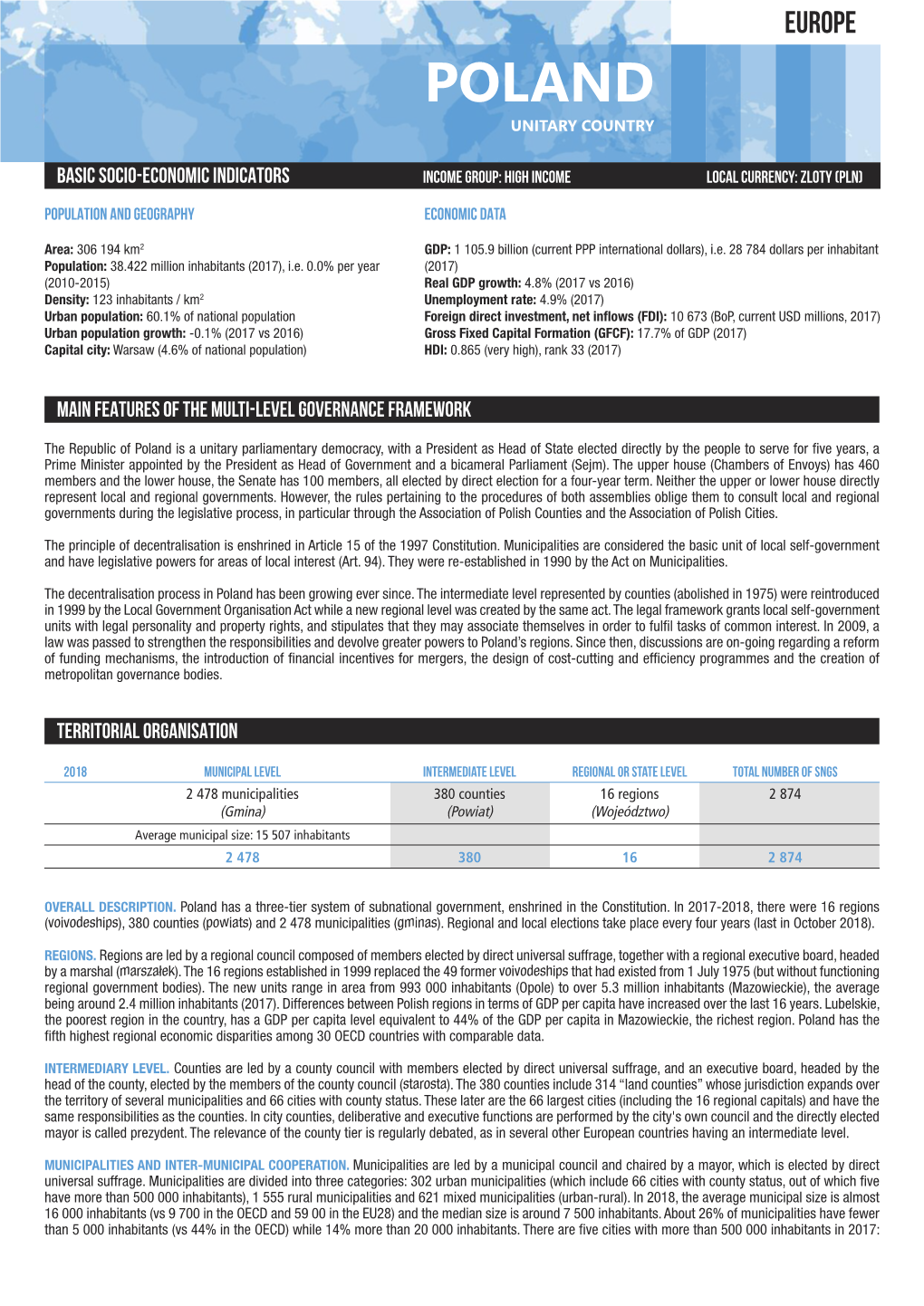

Poland Europe UNITARY COUNTRY

Poland EUROPe UNITARY COUNTRY Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - HIGH INCOME: OECD Local currency - Zloty (PLN) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 312 679 km2 GDP: 960.2 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 24 952 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), 38.484 REAL GDP GROWTH: 3.3% (2014 vs 2013) a decrease of 0.0% per year (2010-14) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 123 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 17 275 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 60.6% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 20% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Warsaw (4.5% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.843 (very high), rank 36 Sources: OECD, Eurostat, World Bank, UNDP, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government responsibilities MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 2 478 380 16 2 874 municipalities counties regions (gmina) (powiat) (województwo) Average municipal size: 15 530 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. Poland has a three-tier system of subnational government, enshrined in the Constitution ratified in 1997. The regional level (voivodeships) was created by the 1999 Local Government Organisation Act. The intermediate level is made up of counties which were abolished in 1975 and re-established in 1999. Among the counties, 314 are “rural counties” and 66 are urban municipalities with county status. Having more than 100 000 inhabitants, they exercise both municipal and county responsibilities. Municipalities, re-established in 1990, are divided into three categories: urban municipalities, rural municipalities and mixed municipalities. -

Societies East European Politics &

East European Politics & Societies http://eep.sagepub.com Leading the Way to Regionalization in Post-Communist Europe: An Examination of the Process and Outcomes of Regional Reform in Poland Jennifer A. Yoder East European Politics and Societies 2007; 21; 424 DOI: 10.1177/0888325407303786 The online version of this article can be found at: http://eep.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/21/3/424 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: American Council of Learned Societies Additional services and information for East European Politics & Societies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://eep.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://eep.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://eep.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/21/3/424 Downloaded from http://eep.sagepub.com at Glasgow University Library on January 9, 2009 Leading the Way to Regionalization in Post-Communist Europe: An Examination of the Process and Outcomes of Regional Reform in Poland Jennifer A. Yoder* This article examines Poland’s process of regionalization since the late 1990s. It identifies several factors that led Poland to introduce self-government at the regional level both earlier and to a greater extent than its neighbors in East Central Europe. The analysis then turns to the competences and financing of the Polish regions, or voivodeships. Although Poland has taken steps to decentralize, it remains a unitary state. Keywords: Poland; decentralization; regionalization; regions; self-government In 1998, the Poles elected members of new regional councils, fol- lowed by the Czechs in 2000, and the Slovaks in 2002. -

Transnational Labour Migration Between Poland and Germany: the Case of Upper Silesia

Centrum Stosunków Międzynarodowych Center for International Relations Reports&Analyses 4/06 Ewa Palenga-Möllenbeck Transnational Labour Migration between Poland and Germany: The Case of Upper Silesia The Report was written in cooperation with the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, within the framework of the project 'Transatlantic Security Challenges and Dillemas for the European Migration Policy', sponsored by the German Marshall Fund of the United States. CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS ul. Emilii Plater 25, 00-688 Warszawa TEL.: (22) 646 52 67, FAX: (22) 646 52 58 www.csm.org.pl, [email protected] Center for International Relations© Ewa Palenga-Möllenbeck Transnational Labour Migration between Poland and Germany: The Case of Upper Silesia 1. Introduction The relation of nation state and transnationalism can be considered as part of a broader discussion on the sovereignty of the nation state, which is faced with phenomena labelled “postnational”, “supernational”, “global”, “glocal” “local” and, finally, “transnational”. “Transnationalism”, conceived of as trans-border relations and involvements of nation-state citizens, is happening across, transversing the borders of “container-type” nation states and thus challenging their claims to sovereignty and loyalty. That said, transnational practices are not “fluid”, but, as Ewa Morawska (2001:196) never tires to emphasise, “place and time bounded”. The great majority of empirical studies on transnationalism (cf. Levitt et al. 2003: 568) show that nation-states and their policies do matter for forms and contents of transnationalism. National policies can even actively encourage the development of transnational practices. The case I would like to describe in this paper is an interesting example of this interaction between nation-state policy (specifically, dual citizenship), and transnational tendencies. -

Challenges of Regional Development in the Context of Population Ageing. Analysis Based on the Example of Opolskie Voivodeship

sustainability Article Challenges of Regional Development in the Context of Population Ageing. Analysis Based on the Example of Opolskie Voivodeship Krystian Heffner 1, Brygida Klemens 2,* and Brygida Solga 2 1 Faculty of Economics, University of Economics in Katowice, ul. 1 Maja 50, 40-287 Katowice, Poland; heff[email protected] 2 Faculty of Economics and Management, Opole University of Technology, ul. Luboszycka 7, 45-036 Opole, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-6064-48067 Received: 19 July 2019; Accepted: 16 September 2019; Published: 23 September 2019 Abstract: Demographic changes, primarily the problem of progressive ageing, are one of the key challenges to development in Poland. The Opolskie voivodeship belongs to the regions characterised by extremely unfavourable demographic phenomena. This is because some population changes here have a broader dimension than on average in Poland and in the EU. Thereby, they have far-reaching as well as complex economic and social consequences in the region. Due to the fact that demographic processes are determined in the long term, and it is extremely difficult to influence them in the short term, the adaptation of social and economic spheres and, at the same time, the use of specific opportunities resulting from these changes, seems a useful strategy for regional development policy. Therefore, in the context of senioral policy, complex, coherent and diversified activities in the sphere of growth of professional activity of elderly people, support for life-long learning, improvement of seniors’ living conditions, including the development of health infrastructure, and seniors’ integration in society prove to be necessary. -

Natural Values As a Factor in the Location of Residential Investments

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bernaciak, Arnold; Strzelecka, Natalia Article Natural values as a factor in the location of residential investments Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES) Provided in Cooperation with: Opole University Suggested Citation: Bernaciak, Arnold; Strzelecka, Natalia (2014) : Natural values as a factor in the location of residential investments, Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES), ISSN 2081-8319, Opole University, Faculty of Economics, Opole, Vol. 14, Iss. 2, pp. 149-162 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/178854 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu www.ees.uni.opole.pl ISSN paper version 1642-2597 ISSN electronic version 2081-8319 Economic and Environmental Studies Vol. -

Prezentacja Programu Powerpoint

African swine fever in Poland – update General Veterinary Inspectorate 11 December 2018 Update on epizootic situation in pigs ASF outbreaks in pigs in 2018 1 January – 23 November 2018: 109 ASF outbreaks in pigs The last outbreak was confirmed on 19 September in backyard holding in the area listed in Part III of the Annex to CID 2014/709/EU In total 213 outbreaks since the first one in 2014 Update on epizootic situation in wild boar ASF cases in wild boar in 2018 1 January – 10 December 2018: 2286 ASF cases in wild boar In total 3190 cases since the first one on 17 February 2014 (10 December 2018) The cases of the ASF, there were confirmed in Part 1 or in Part 2 near the border with Part I of the Annex of CID 2014/709/UE, last amendment CID 2018/1856 3143 case of ASF (2018/2239) 1 shot wild boar (female, 1 y.o.) confirmed on 30.11.18. (part 1, Lubelskie Region) The results from NVRI: RT-PCR- /Elisa+, IPT+. The distance from nearest case of ASF- app.19 km. (2542 case of ASF - 1 dead wild boar, confirmed on 17.07.2018; RT-PCR+) The proposal of changes of the Annex to CID 2014/709 Enlargement of part 2: - municipality Werbkowice in hrubieszowski district - municipality Tyszowce and - part of municipality of Łaszczów North from the road no. 852 in tomaszowski district. Enlargement of Part 1: - municipality Rachanie in tomaszowski district. 3170 case of ASF (2018/2266) 1 shot wild boar (female, 2 y.o.) confirmed on 05.12.18 (Warmińsko – Mazurskie Region, part 1) The results from NVRI: RT-PCR+ The distance from nearest case of ASF –app.14 km. -

Chapter 1. Urban Substructures As a Way to Build a Balanced Spatial

In: Urban Space: An Overview ISBN: 978-1-53617-481-6 Editor: Mia S. Johnsen © 2020 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 URBAN SUBSTRUCTURES AS A WAY TO BUILD A BALANCED SPATIAL AND FUNCTIONAL STRUCTURE OF CITIES Lidia Mierzejewska Faculty of Socio-Economic Geography and Spatial Management Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland ABSTRACT According to the tenets of sustainable development, the spatial structure of a city should be designed to enable satisfying the residents’ needs in the most effective and egalitarian way while saving its resources. These conditions are fulfilled by an urban spatial structure based on urban substructures. The term ‘urban substructure’ defines certain intra-urban, functional wholes operating according to the model of a nodal region. Morphologically, the substructure is composed of a core (sub-centre), concentrating goods and services meeting daily needs of inhabitants and the area of its influence. Built from substructures, an urban spatial and functional structure is polycentric, condensed around each sub-centre, demonstrating at the same time certain features of dispersion. The article aims to present the theoretical assumptions of the conception of urban 2 Lidia Mierzejewska substructures, historical examples of such substructures (jurydyki – former settlements in Poland outside a royal city, or beguinages, etc.) and also the benefits resulting from the creation of the spatial form of the city composed of substructures. The article is theoretical in character and relates to numerous theories and spatial development conceptions, including the conception of polycentricity. A polycentric spatial structure in various spatial scales has many advantages. There is still lack of approaches that would refer to the local scale of a city. -

The Łódź Atlas

THE ŁÓDŹ ATLAS a higher development standard at least for having trees planted on the sides, or for the neat Literature architectural designs of the buildings (Pasaż Meyera). One characteristic feature of the city’s B a d z i a k K., 1976, Geneza i rozwój łódzkiego węzła komunikacyjnego (do 1914 r.), Rocznik Łódzki, t. XXI (XXIV). development was that there were built up the street frontages, which practice had already Sheet V: Łódź in the high industrial period Bogusz A., 1993, Fabryczne Kluby Sportowe Łodzi , Muzeum Sportu i Turystyki, Łódź. commenced in the first half of 19th century, that the municipal rights granted to the artisan Bogusz A., 1992, Niemieckie Stowarzyszenia Sportowe Łodzi 1824–1939, Muzeum Sportu i Turystyki, V settlements did not at all envisage: first in the streets perpendicular to Piotrkowska Street, Łódź. Jacek Wesołowski and then in those parallel to it. In this way created were divided configurations of secondary Bogusz A., 1992, Żydowskie Stowarzyszenia Sportowe Łodzi 1897–1939, Muzeum Sportu i Turystyki, Łódź. Lasociń s k i D., B o n i s ł awski R., Koliń s k i M., 2001, Łódź – przewodnik, Piątek Trzynaste- building plots that were perpendicular to the original extended plots. One important central go, Łódź. city street that waited to be developed until the 1880’s was Dzika Street which the planners Dzieje Żydów w Łodzi 1820–1944. Wybrane problemy, 1991, red. W. P u ś i S. L i s z e w s k i, Łódź. In the period between 1850 and 1914 under study in this sheet V, Łódź evolved from tried to give a noble character by locating there a public park and a middle school building, Elektrownia Łódzka 1907–1932, 1932, Łódzkie Towarzystwo Elektryczne SA, Łódź.