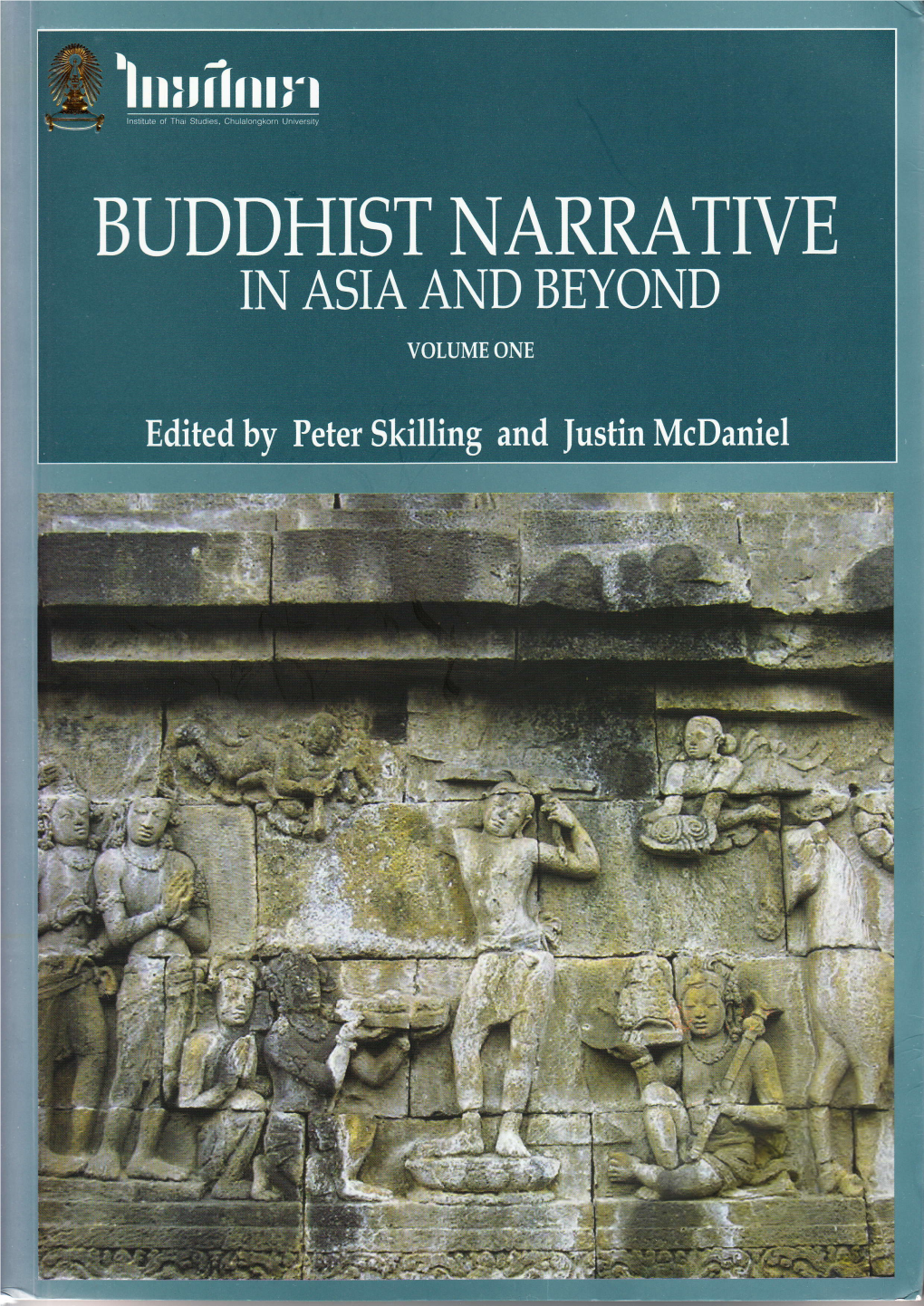

Māndhātar, the Universal Monarch, and the Meaning of Representations of the Cakravartin in the Amaravati School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANSWERED ON:25.11.2014 TOURIST SITES Singh Shri Rama Kishore

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TOURISM LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:403 ANSWERED ON:25.11.2014 TOURIST SITES Singh Shri Rama Kishore Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) whether tourist sites have been categorised grade-wise in the country and if so, the details thereof; (b) the details of tourist sites covered under Buddhist circuit and developed as world heritage tourist sites during the last three years and the current year; (c) whether the Government has any tourism related proposals for Vaishali in Bihar including financial assistance; and (d) if so, the details thereof? Answer MINISTER OF STATE FOR TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (DR. MAHESH SHARMA) (a): Madam. At present there is no grade wise categorization of tourist sites. (b): The Ministry of Tourism has identified following three circuits to be developed as Buddhist Circuits in the country with the help of Central Government/State Government/Private stake holders: Circuit 1: The Dharmayatra or the Sacred Circuit - This will be a 5 to 7 days circuit and will include visits to Gaya (Bodhgaya), Varanasi (Sarnath), Kushinagar, Piparva (Kapilvastu) with a day trip to Lumbini in Nepal. Circuit 2: Extended Dharmayatra or Extended Sacred Circuit or Retracing Buddha's Footsteps - This will be a 10 to 15 day circuit and will include visits to Bodhgaya (Nalanda, Rajgir, Barabar caves, Pragbodhi Hill, Gaya), Patna (Vaishali, Lauriya Nandangarh, Lauriya Areraj, Kesariya, Patna Museum), Varanasi (Sarnath), Kushinagar, Piparva (Kapilvastu, Shravasti, Sankisa) with a day trip to Lumbini in Nepal. Circuit 3: Buddhist Heritage Trails (State Circuits). i. Jammu and Kashmir - Ladakh, Srinagar (Harwan, Parihaspora) and Jammu (Ambaran). -

Ancient Universities in India

Ancient Universities in India Ancient alanda University Nalanda is an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India from 427 to 1197. Nalanda was established in the 5th century AD in Bihar, India. Founded in 427 in northeastern India, not far from what is today the southern border of Nepal, it survived until 1197. It was devoted to Buddhist studies, but it also trained students in fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, politics and the art of war. The center had eight separate compounds, 10 temples, meditation halls, classrooms, lakes and parks. It had a nine-story library where monks meticulously copied books and documents so that individual scholars could have their own collections. It had dormitories for students, perhaps a first for an educational institution, housing 10,000 students in the university’s heyday and providing accommodations for 2,000 professors. Nalanda University attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia and Turkey. A half hour bus ride from Rajgir is Nalanda, the site of the world's first University. Although the site was a pilgrimage destination from the 1st Century A.D., it has a link with the Buddha as he often came here and two of his chief disciples, Sariputra and Moggallana, came from this area. The large stupa is known as Sariputra's Stupa, marking the spot not only where his relics are entombed, but where he was supposedly born. The site has a number of small monasteries where the monks lived and studied and many of them were rebuilt over the centuries. We were told that one of the cells belonged to Naropa, who was instrumental in bringing Buddism to Tibet, along with such Nalanda luminaries as Shantirakshita and Padmasambhava. -

Changing Forms and Cultural Identity: Religious and Secular Iconographies

Changing Forms and Cultural Identity: Religious and Secular Iconographies VOL. 1 SOUTH ASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ART Papers from the 20th conference of the European Association for South Asian Archaeology and Art held in Vienna from 4th to 9th of July 2010 KLIMBURG-SALTER, DEBORAH & LINDA LOJDA (EDS). ! TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 7 Deborah Klimburg-Salter DB)<-.$%&E#.,6&.$,&F%-)"&?.";6&#$&!)8.B)&!:A=")6&:$&2-/"-=%& . 9 Chandreyi Basu +&G)"".'#%%.&>)B:)7&7"#8&+-:''-.%%"/&H&I=$&2."J=)5&I#B."&K-.":#%&#"&LLLM . 23 Marion Frenger ?.:%")N.&.$,&%-)&O.6%&2=,,-.6*&P$%)".'%:#$6&Q)%R))$&E.$,-/".&.$,&S#"%-)"$&P$,:. 29 Kurt A. Behrendt F$&%-)&S)')66:%N&K#$%)T%=.B:6.%:#$*&.&S.A.".,)(.%/&.$,&#%-)"&I)8:3$=,)&U#8)$&:$&E.$,-/".$& Representations of the Buddha’s Life . 41 Katia Juhel F$A#:$A&I%=,:)6&2#,-:6.%%(.&P8.A)"N&7"#8&E").%)"&E.$,-/".*&G="Q.$&F"$.8)$%.%:#$&:$&%-)& !#"8&U:$A),3V:#$&OB.J=)6& . 53 Carolyn Woodford Schmidt I;.$,.&:$&E.$,-/".*&+&W:$,=&E#,&:$&.&2=,,-:6%&D$(:"#$8)$%M . 71 Kirsten Southworth S#$32=,,-:6%&S."".%:()&I')$)6&.%&S.A."@=$.;#$,.& . 77 Monika Zin +XY.8.-/Q-.N.&+(.B#;:%)1(.".&:$&%-)&U)6%)"$&Z)''.$*&2=,,-:6%&O.%"#$.A)&.$,&G".,)&Q)%R))$&%-) [7%-&.$,&6:T%-&')$%="N&KD&& . 91 Pia Brancaccio Z)6:A$:$A&.&S)R&W#N6.\.&G)8<B)&:$&]."$.%.;.&&& . 99 Adam Hardy +&?.A$:[')$%&E=<%.&G)"".'#%%.&9/6=,)(.39:X^=&P8.A)&7"#8&%-)&Z.(:,&S.B:$&K#BB)'%:#$& . 119 Gouriswar Bhattacharya G-)&W:$,=&I'=B<%=")6&7"#8&O/-/"<="&>)'#$6:,)"),& . 131 Vincent Lefèvre [5] TABLE OF CONTENTS Ten Illustrated Leaves from a !"#$"%"&'()Manuscript in a Private European Collection . -

Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, Vol. 2, May 2012

VOLUME 2 (MAY 2012) ISSN: 2047-1076! ! Journal of the ! ! Oxford ! ! ! Centre for ! ! Buddhist ! ! Studies ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! The Oxford Centre for ! Buddhist Studies A Recognised Independent http://www.ocbs.org/ Centre of the University of Oxford! JOURNAL OF THE OXFORD CENTRE FOR BUDDHIST STUDIES May Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies Volume May : - Published by the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies www.ocbs.org Wolfson College, Linton Road, Oxford, , United Kingdom Authors retain copyright of their articles. Editorial Board Prof. Richard Gombrich (General Editor): [email protected] Dr Tse-fu Kuan: [email protected] Dr Karma Phuntsho: [email protected] Dr Noa Ronkin: [email protected] Dr Alex Wynne: [email protected] All submissions should be sent to: [email protected]. Production team Operations and Development Manager: Steven Egan Production Manager: Dr Tomoyuki Kono Development Consultant: Dr Paola Tinti Annual subscription rates Students: Individuals: Institutions: Universities: Countries from the following list receive discount on all the above prices: Bangladesh, Burma, Laos, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, ailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, In- donesia, Pakistan, all African Countries For more information on subscriptions, please go to www.ocbs.org/journal. Contents Contents List of Contributors Editorial. R G Teaching the Abhidharma in the Heaven of the irty-three, e Buddha and his Mother. A Burning Yourself: Paticca. Samuppāda as a Description of the Arising of a False Sense of Self Modeled on Vedic Rituals. L B A comparison of the Chinese and Pāli versions of the Bala Samyukta. , a collection of early Buddhist discourses on “Powers” (Bala). -

Association of Buddhist Studies

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 36 / 37 2013 / 2014 (2015) The Journal of the International EDITORIAL BOARD Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of KELLNER Birgit Buddhist Studies, Inc. As a peer- STRAUCH Ingo reviewed journal, it welcomes scholarly Joint Editors contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. JIABS is published yearly. BUSWELL Robert CHEN Jinhua The JIABS is now available online in open access at http://journals.ub.uni- COLLINS Steven heidelberg.de/index.php/jiabs. Articles COX Collett become available online for free 24 months after their appearance in print. GÓMEZ Luis O. Current articles are not accessible on- HARRISON Paul line. Subscribers can choose between VON HINÜBER Oskar receiving new issues in print or as PDF. JACKSON Roger Manuscripts should preferably be JAINI Padmanabh S. submitted as e-mail attachments to: KATSURA Shōryū [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, KUO Li-ying in two different formats: in PDF-format, LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or MACDONALD Alexander Open-Document-Format (created e.g. by Open Office). SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina SEYFORT RUEGG David Address subscription orders and dues, SHARF Robert changes of address, and business correspondence (including advertising STEINKELLNER Ernst orders) to: TILLEMANS Tom Dr. Danielle Feller, IABS Assistant-Treasurer, IABS Department of Slavic and South Asian Studies (SLAS) Cover: Cristina Scherrer-Schaub Anthropole University of Lausanne Font: “Gandhari Unicode” CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland designed by Andrew Glass E-mail: [email protected] (http://andrewglass.org/fonts.php) Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net © Copyright 2015 by the Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 65 per International Association of year for individuals and USD 105 per Buddhist Studies, Inc. -

Corporate Bodies in Early South Asian Buddhism: Some Relics and Their Sponsors According to Epigraphy

religions Article Corporate Bodies in Early South Asian Buddhism: Some Relics and Their Sponsors According to Epigraphy Matthew D. Milligan Department of Philosophy, Religion, and Liberal Studies, College of Arts and Sciences, Georgia College & State University, 231 W. Hancock St., Milledgeville, GA 31061, USA; [email protected] Received: 8 November 2018; Accepted: 12 December 2018; Published: 22 December 2018 Abstract: Some of the earliest South Asian Buddhist historical records pertain to the enshrinement of relics, some of which were linked to the Buddha and others associated with prominent monastic teachers and their pupils. Who were the people primarily responsible for these enshrinements? How did the social status of these people represent Buddhism as a burgeoning institution? This paper utilizes early Prakrit inscriptions from India and Sri Lanka to reconsider who was interested in enshrining these relics and what, if any, connection they made have had with each other. Traditional accounts of reliquary enshrinement suggest that king A´soka began the enterprise of setting up the Buddha’s corporeal body for worship but his own inscriptions cast doubt as to the importance he may have placed in the construction of stupa¯ -s and the widespread distribution of relics. Instead, as evidenced in epigraphy, inclusive corporations of individuals may have instigated, or, at the very least, became the torchbearers for, reliquary enshrinement as a salvific enterprise. Such corporations comprised of monastics as well as non-monastics and seemed to increasingly become more managerial over time. Eventually, culminating at places like Sanchi, the enshrinement of the corporeal remains of regionally famous monks partially supplanted the corporeal remains of the Buddha. -

Finding the “Early Medieval” in South Asian Archaeology

Finding the “Early Medieval” in South Asian Archaeology JASON D. HAWKES introduction The “early” or “premedieval” period exists as a well-established, if poorly defined, period in the study of South Asia’s past. Broadly accepted to have extended from around the seventh to thirteenth century c.e., the term “early medieval” has emerged in scholarship to define a particular phase of social and cultural development that mark it as being broadly distinguishable from the earlier ancient period that came before. Developments held to define the beginning of the early medieval include: the emergence of new political structures in both North and South India, a reorientation of exchange networks and urbanism across the subcontinent, and the crystallization of distinct regional cultures and identities manifest in the appearance of diverse litera- tures and arts. Yet, because these developments did not occur in the same way, or in- deed at the same time throughout the subcontinent, and with little consensus as to what marks the end of this early phase of the medieval and the start of the later medieval period that follows, the concept of the early medieval remains problematic (Singh 2011). Questions exist as to whether it should be deemed a definable period in its own right, central to which are wider questions about the meaning and validity of the term medieval in South Asian history. These issues have been the subject of much discussion. Yet, what is even more important, albeit rarely discussed, are the ways in which the early medieval is studied almost exclusively through documentary sources (involving texts and inscriptions) and monumental remains. -

The Looping Journey of Buddhism: from India to India

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-9, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in The Looping Journey of Buddhism: From India To India Jyoti Gajbhiye Former Lecturer in Yashwant Rao Chawhan Open University. Abstract: This research paper aims to show how were situated along the Indus valley in Punjab and Buddhism rose and fell in India, with India Sindh. retaining its unique position as the country of birth Around 2000 BC, the Aarya travelers and invaders for Buddhism. The paper refers to the notion that came to India. The native people who were the native people of India were primarily Buddhist. Dravidian, were systematically subdued and It also examines how Buddhism was affected by defeated. various socio-religious factors. It follows how They made their own culture called “vedik Buddhism had spread all over the world and again Sanskriti”. Their beliefs lay in elements such Yajna came back to India with the efforts of many social (sacred fire) and other such rituals. During workers, monks, scholars, travelers, kings and Buddha’s time there were two cultures “Shraman religious figures combined. It examines the Sanskriti” and “vedik Sanskriti”. Shraman Sanskrit contribution of monuments, how various texts and was developed by “Sindhu Sanskriti” which their translations acted as catalysts; and the believes In hard work, equality and peace. contribution of European Indologists towards Archaeological surveys and excavations produced spreading Buddhism in Western countries. The many pieces of evidence that prove that the original major question the paper tackles is how and why natives of India are Buddhist. Referring to an Buddhism ebbed away from India, and also what article from Gail Omvedt’s book “Buddhism in we can learn from the way it came back. -

Buddhism in the Northern Deccan Under The

BUDDHISM IN THE NORTHERN DECCAN UNDER THE SATAVAHANA RULERS C a ' & C > - Z Z f /9> & by Jayadevanandasara Hettiarachchy Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of London 1973* ProQuest Number: 10731427 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731427 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This study deals with the history of Buddhism in the northern Deccan during the Satavahana period. The first chapter examines the evidence relating to the first appearance of Buddhism in this area, its timing and the support by the state and different sections of the population. This is followed by a discussion of the problems surrounding the chronology of the Satavahana dynasty and evidence is advanced to support the ’shorter chronology*. In the third chapter the Buddhist monuments attributable to the Satavahana period are dated utilising the chronology of the Satavahanas provided in the second chapter. The inscriptional evidence provided by these monuments is described in detail. The fourth chapter contains an analysis and description of the sects and sub-sects which constituted the Buddhist Order. -

The Buddhist Cosmopolis: Universal Welfare, Universal Outreach, Universal Message

Journal of Buddhist Studies, Vol. XV, 2018 (Of-print) The Buddhist Cosmopolis: Universal Welfare, Universal Outreach, Universal Message Peter Skilling Published by Centre for Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka & The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong JOURNAL OF BUDDHIST STUDIES VOLUME XV CENTRE FOR BUDDHIST STUDIES, SRI LANKA & THE BUDDHA-DHARMA CENTRE OF HONG KONG DECEMBER 2018 © Centre for Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka & The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong ISBN 978-988-16820-1-7 Published by Centre for Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka & The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong with the sponsorship of the Glorious Sun Charity Group, Hong Kong (旭日慈善基金). EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Ratna Handurukande Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, University of Peradeniya. Y karunadasa Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, University of Kelaniya Visiting Professor, The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong. Oliver abeynayake Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, Buddhist and Pali University of Sri Lanka. Chandima Wijebandara Ph.D. Professor, University of Sri Jayewardenepura. Sumanapala GalmanGoda Ph.D. Professor, University of Kelaniya. Academic Coordinator, Nāgānanda International Institute of Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka. Toshiichi endo Ph.D. Visiting Professor, Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong. EDITOR Bhikkhu KL dHammajoti 法光 Director, The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong. CONTENTS On the Two Paths Theory: Replies to Criticism 1 Bhikkhu AnālAyo Discourses on the Establishments of Mindfulness (smṛtyupasthānas) Quoted in Śamathadeva’s Abhidharmakośapāyikā-ṭīkā 23 Bhikkhunī DhAmmADinnā -

AP Board Class 6 Social Science Chapter 20

Improve your learning Sculptures and Buildings 1) Brief the importance of languages. 20 2) How can you say that Aryabhata was the father of astronomy? CHAPTER 3) Differentiate between Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita. 4) Mention a few inventions in Mathematics. Archeologists digging very ancient cities of Indus Valley found some very nice stone and bronze sculptures besides seals carved on stones 5) Look at a currency note and write down difference scripts on them. Identify the and baked clay figurines. These were made some 4000 years ago. You language in which they are written. Is the same script used for different languages? can see some of their pictures here. You can see that these depict everything in a natural manner. We don’t know what they were used for. Which are they? 6) Refer to any general knowledge book and list out five great books in Telugu language and other languages. Project : Prepare a Flow Chart on the establishment of languages. Fig: 20.1. A small bust of a male person of Fig: 20.3. A bronze statue of a importance – was he a priest or a king? girl standing Fig: 20.2. A beautiful Harappan Fig: 20.4. A mother goddess figurine Seal showing a bull of terracotta. 170 Social Studies Free Distribution by Govt. of A.P. A little later the art of casting metal These pillars and the Lion Capital Portrait of Ashoka from Stupa. Look at the photo. You can see that figures spread to Maharashtra. Some very represent the power and majesty of the Kanaganahalli it is like a hemisphere (half ball) – just as exquisite bronze figures were found during Mauryan emperors. -

Aspects of Ancient Indian Art and Architecture

ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE M.A. History Semester - I MAHIS - 101 SHRI VENKATESHWARA UNIVERSITY UTTAR PRADESH-244236 BOARD OF STUDIES Prof (Dr.) P.K.Bharti Vice Chancellor Dr. Rajesh Singh Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Dr. S.K.Bhogal, Professor Dr. Yogeshwar Prasad Sharma, Professor Dr. Uma Mishra, Asst. Professor COURSE CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Shakeel Kausar Dy. Registrar Author: Dr. Vedbrat Tiwari, Assistant Professor, Department of History, College of Vocational Studies, University of Delhi Copyright © Author, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301