Quantifying Film and Television Tourism in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Tourism Action Plan

BUSINESS TOURISM ACTION PLAN Vision To increase the value of England's business tourism market by 5% year on year by 2020. Objectives 1. To maximise England's strong and competitive brand values in marketing it as a business tourism destination. 2. To leverage England's expertise in medicine/science, academia and industry to gain competitive advantage. 3. To ensure all England's facilities, products and services continue to meet market needs to increase England’s competitive success. 4. To ensure the importance of business tourism maintains a high profile with public and private sector stakeholders. What is Business Tourism? Business tourism includes visitors participating in the following activities: Association/Charity/Institute/Society Events Governmental meetings & conferences Corporate Events – dinners, product launches, conferences, awards etc Incentive travel Corporate hospitality Exhibitions & trade shows Independent business travellers Why take action on Business Tourism? Conferences, meetings and other business events play a vital role in economic, professional and educational development in England by providing important opportunities to communicate, educate, motivate and network. England leads the world in specialist areas of innovation such as biotechnology, digital media, genetics and nano-technologies. It also plays a pivotal role in finance, insurance and business services as well as having globally admired expertise in creative industries. This specialist expertise enables England to develop conferences and meetings contributing £15 billion in economic impact in 2009, plus exhibitions and trade shows worth £7.4 billion and a further £1 billion each from incentive travel and corporate hospitality (Source:BVEP). Additionally, trade transacted at exhibitions and other business meetings is conservatively estimated to be worth over £80 billion. -

Almatourism Special Issue N

AlmaTourism Special Issue N. 4, 2015: Beeton S., Cavicchi A., Not Quite Under the Tuscan Sun… the Potential of Film Tourism in Marche Region AlmaTourism Journal of Tourism, Culture and Territorial Development ___________________________________________________________ Not Quite Under the Tuscan Sun… the Potential of Film Tourism in Marche Region Beeton, S.* La Trobe University (Australia) Cavicchi, A.† University of Macerata (Italy) ABSTRACT The relationship between film and tourism is complex and at times often subtle – not all movies directly encourage tourism, but they can influence tourist images as well as provide additional aspects to the tourist experience. This conceptual paper considers the role that film can play to encourage and enhance tourism in the Marche Region of Italy. Based on theoretical knowledge developed to date, a process to develop film tourism product is proposed. Such a practical application of academic knowledge will also provide data with which to further develop theoretical models in the field. _________________________________________________________ Keywords: Film-induced tourism, Film Commission, Italy, Rural areas * E-mail address: [email protected] † E-mail address: [email protected] almatourism.unibo.it ISSN 2036-5195 146 This article is released under a Creative Commons - Attribution 3.0 license. AlmaTourism Special Issue N. 4, 2015: Beeton S., Cavicchi A., Not Quite Under the Tuscan Sun… the Potential of Film Tourism in Marche Region Introduction People have been visiting Italy for thousands of years, with the notion of the ‘Grand Tour’ of the 18th Century acknowledged as one of the antecedents of modern day tourism, while others argue persuasively that tourism was well established in that region far earlier, such as during the Roman Empire (Lomine, 2005). -

The Greater Manchester Strategy for the Visitor Economy 2014 - 2020 Introduction

The GreaTer ManchesTer sTraTeGy for The VisiTor econoMy 2014 - 2020 inTroducTion This strategy sets out the strategic direction for the visitor economy from 2014 through to 2020 and is the strategic framework for the whole of the Greater Manchester city-region: Bolton, Bury, Manchester, Oldham, Rochdale, Salford, Stockport, Tameside, Trafford, and Wigan. The strategy has been developed through consultation with members and stakeholders of Marketing Manchester, in particular with input from the Manchester Visitor Economy Forum who will be responsible for monitoring delivery of the identified action areas and progress against the targets set. Albert Square, Manchester 2 The Greater Manchester strategy for the Visitor economy 2014 - 2020 Policy conTexT Holcombe Hill, Bury Exchange Square, Manchester The strategic direction of tourism in Greater Manchester is Four interdependent objectives have been identified to informed by the following national and sub-regional documents: address the opportunities and challenges for England’s visitor economy: • Britain Tourism Strategy. Delivering a Golden Legacy: a growth strategy for inbound tourism • To increase England’s share of global visitor markets 2012 - 2020 (VisitBritain) • To offer visitors compelling destinations • England: A Strategic Framework for Tourism • To champion a successful, thriving tourism industry 2010 - 2020 (VisitEngland) • To facilitate greater engagement between the • Greater Manchester Strategy 2013 - 2020 visitor and the experience Stronger Together Visit Manchester is a key -

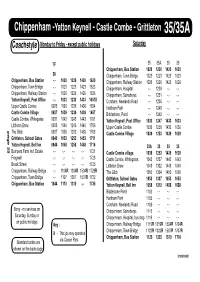

35/35A Key: Y

Chippenham - Kington St Michael 99 Monday to Friday - except public holidays Coachstyle Faresaver Service number 35 Chippenham, Bus Station -.- -.- 0920 1015 1115 1315 1415 -.- 1620 1745 Chippenham, Town Bridge 0718 0818 0923 1018 1118 1318 1418 1508 1623 1748 Chippenham, Railway Sation 0721 0821 0925R 1021R 1121R 1321R 1421R -.- 1626 1751 Sheldon School (school days only) -.- -.- -.- -.- -.- -.- -.- 1510 -.- -.- Monkton Park, Lady Coventry Road -.- -.- -.- 1023 1123 1323 1428 -.- -.- 1753R Chippenham, Railway Station 0721 0821 0925R 1025 1125 1325 -.- -.- 1626 1755 Bristol Road 0724 0824 0927 1027 1127 1327 -.- 1511 -.- 1757 Brook Street -.- 0825 0928 1028 1128 1328 -.- -.- -.- -.- Redland -.- 0826 0929 1029 1129 1329 -.- -.- -.- -.- page 64 Frogwell 0728R 0828 0931 1031 1131 1331 -.- -.- -.- -.- Bumpers Farm Industrial Estate 0730R 0830R 0933 1033 1133 1333 -.- -.- -.- -.- Cepen Park, Stainers Way 0732 -.- 0935 1035 1135 1335 -.- 1518 1636 1801 Morrisons Supermarket 0735 -.- 0938 1038 1138 1338 -.- 1521 1639 1804 Kington St Michael, bus shelter 0740 -.- 0943 1043 1143 1343 -.- 1526 1644y 1809R 35 Key: Kington St Michael, bus shelter 0745 0845 0945 1045 1145 1345 -.- 1545 -.- y - Bus continues Morrisons Supermarket 0752 0852 0952 1052 1152 1352 -.- 1552 -.- to Yatton Keynell Cepen Park, Stainers Way 0754 0854 0954 1054 1154 1354 -.- 1554 -.- Bumpers Farm Industrial Estate -.- 0856 0956 1056 1156 1356 -.- 1556 1721 Frogwell -.- 0858 0958 1058 1158 1358 -.- 1558 1723 See next page for Brook Street 0800 0900R 1000R 1100R 1200R 1400R -.- -

Great Chalfield, Wiltshire: Archaeology and History (Notes for Visitors, Prepared by the Royal Archaeological Institute, 2017)

Great Chalfield, Wiltshire: archaeology and history (notes for visitors, prepared by the Royal Archaeological Institute, 2017) Great Chalfield manor belonged to a branch of the Percy family in the Middle Ages. One of them probably had the moat dug and the internal stone wall, of which a part survives, built, possibly in the thirteenth century. Its bastions have the remains of arrow-slits, unless those are later romanticizing features. The site would have been defensible, though without a strong tower could hardly have been regarded as a castle; the Percy house was a courtyard, with a tower attached to one range, but its diameter is too small for that to have been much more than a staircase turret. The house went through various owners and other vicissitudes, but was rescued by a Wiltshire business-man, who employed W. H. Brakspear as architect (see Paul Jack’s contribution, below). It is now owned by the National Trust (plan reproduced with permission of NT Images). Security rather than impregnability is likely to have been the intention of Thomas Tropenell, the builder of most of the surviving house. He was a local man and a lawyer who acquired the estate seemingly on a lease, and subsequently and after much litigation by purchase, during the late 1420s/60s (Driver 2000). In the house is the large and impressive cartulary that documents these struggles, which are typical of the inter- and intra-family feuding that characterized the fifteenth century, even below the level of royal battles and hollow crowns. Tropenell was adviser to Lord Hungerford, the dominant local baron; he was not therefore going to build anything that looked like a castle to challenge nearby Farleigh. -

Hotels in Islington

Hotels in Islington Prepared for: LB Islington 1 By RAMIDUS CONSULTING LIMITED Date: 18th January 2016 Hotels in Islington Contents Chapter Page Management Summary ii 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 National trends 1 3.0 Tourism and hotel priorities in London & Islington 8 4.0 Tourism in London and Islington 15 5.0 Hotels in London and Islington 22 6.0 Conclusions 32 Figures 1 UK and overseas resident staying trips in England 2 2 Hotel rooms by establishment type 4 3 Hotel rooms built, 2003-12 4 4 Number of new build rooms, rebrands and refurbishments, 2003-12 5 5 New openings, 2003-12 5 6 Room occupancy rates in England and London 6 7 Volume and value of staying visitors to London 15 8 Purpose of trip to London 16 9 Share of oversea visitor trips, nights and spend by purpose of trip 16 10 Accommodation used 16 11 Airbnb listings in Islington 17 12 Map of Airbnb listings in Islington 18 13 Key attractions in London 20 14 Hotels in London, 2013 23 15 Current hotel development pipeline in Islington 25 16 Current estimates of visitor accommodation in Islington 26 17 Distribution of all types of accommodation in Islington 27 18 Visitor accommodation in Islington by capacity, December 2015 28 19 Visitor accommodation in Islington by category, December 2015 28 20 Average and total rooms in Islington by type, December 2015 29 21 Hotel/apart-hotel consents in Islington since 2001 29 22 Pipeline hotel projects in Islington 30 23 Pipeline apart-hotel projects in Islington 30 24 Location of pipeline projects in Islington 31 25 Community Infrastructure Levy rates in Islington 32 Annex 1 – Accommodation establishments in Islington 35 Annex 2 – Pipeline developments in Islington 38 Prepared for: LB Islington i By RAMIDUS CONSULTING LIMITED Date: 18th January 2016 Hotels in Islington Management Summary This report has been prepared as part of an Employment Land Study (ELS) for London Borough of Islington during July to December 2015. -

Film-Induced Tourism, the Case Study of ‘Game of Thrones’ TV Series

Film-Induced Tourism, The Case Study of ‘Game of Thrones’ TV series. Nikolaos Dimoudis SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION & LEGAL STUDIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Hospitality and Tourism Management January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece [1] Student Name: Nikolaos Dimoudis SID: 1109150010 Supervisor: Prof. Alkmini Gritzali I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work; I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece [2] Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MSc in Hospitality and Tourism Management at the International Hellenic University. This paper demonstrates the ability of television series as a promotional tool. Not only will the Film-induced tourism phenomenon will be explained, but also the profile of the film tourist will be outlined. A practical case study examines the impact of one of the most popular television series on its filming location, based on data collected from official tourism boards, companies who offer services or products related to a TV series and local accommodation companies. In this part I would like to thank Mrs. Gritzali for her support and guidance and those who responded to the research surveys helping me with my dissertation. Nikolaos Dimoudis 31/01/2018 [3] TAMPLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………....5 1. Theoretical Framework……………………………………………….6 1.1 History of Television………………………………………………6 1.2 History -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Culture, Heritage and Libraries

Public Document Pack Culture, Heritage and Libraries Committee Date: MONDAY, 28 OCTOBER 2013 Time: 11.30am Venue: COMMITTEE ROOMS, 2ND FLOOR, WEST WING, GUILDHALL Members: John Scott (Chairman) Robert Merrett Vivienne Littlechild (Deputy Sylvia Moys Chairman) Barbara Newman Christopher Boden Graham Packham Mark Boleat Alderman Dr Andrew Parmley Deputy Michael Cassidy Ann Pembroke Dennis Cotgrove Judith Pleasance Deputy Billy Dove Emma Price Deputy Anthony Eskenzi Deputy Gerald Pulman Kevin Everett Stephen Quilter Lucy Frew Deputy Richard Regan Ibthayhaj Gani Alderman William Russell Deputy the Revd Stephen Haines Deputy Dr Giles Shilson Brian Harris Mark Wheatley Tom Hoffman Alderman David Graves (Ex-Officio Wendy Hyde Member) Jamie Ingham Clark Deputy Catherine McGuinness (Ex- Deputy Alastair King Officio Member) Jeremy Mayhew Vacancy Enquiries: Matthew Pitt tel. no.: 020 7332 1425 [email protected] Lunch will be served in Guildhall Club at 1PM John Barradell Town Clerk and Chief Executive AGENDA Part 1 - Public Agenda 1. APOLOGIES 2. MEMBERS' DECLARATIONS UNDER THE CODE OF CONDUCT IN RESPECT OF ITEMS ON THE AGENDA 3. MINUTES To approve the public minutes of the meeting held on 1 July 2013. For Decision (Pages 1 - 6) 4. REPORT OF ACTION TAKEN BETWEEN MEETINGS Report of the Town Clerk. For Information (Pages 7 - 10) 5. GUILDHALL LIBRARY Presentation by the Head of Guildhall Library. For Information 6. CITY OF LONDON FESTIVAL - INTRODUCTION OF NEW DIRECTOR Verbal update by the Director of Culture, Heritage and Libraries. For Information 7. CITY OF LONDON FESTIVAL 2013 PROGRAMME Report of the Director of Culture, Heritage and Libraries. For Information (Pages 11 - 38) 8. -

The Natural History of Wiltshire

The Natural History of Wiltshire John Aubrey The Natural History of Wiltshire Table of Contents The Natural History of Wiltshire.............................................................................................................................1 John Aubrey...................................................................................................................................................2 EDITOR'S PREFACE....................................................................................................................................5 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................12 INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. CHOROGRAPHIA.................................................................................15 CHOROGRAPHIA: LOCAL INFLUENCES. 11.......................................................................................17 EDITOR'S PREFACE..................................................................................................................................21 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................28 INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. CHOROGRAPHIA.................................................................................31 CHOROGRAPHIA: LOCAL INFLUENCES. 11.......................................................................................33 CHAPTER I. AIR........................................................................................................................................36 -

Ancient Market Towns and Beautiful Villages

Ancient Market Towns and Beautiful Villages Wiltshire is blessed with a fantastic variety of historic market towns and stunning picturesque villages, each one with something to offer. Here are a sample of Wiltshire’s beautiful market towns and villages. Amesbury Nestling within a loop of the River Avon alongside the A303, just 1½ miles from Stonehenge, historic Amesbury is a destination not to be missed. With recent evidence of a large settlement from 8820BC and a breath-taking Mesolithic collection, Amesbury History Centre will amaze visitors with its story of the town where history began. Bradford on Avon The unspoilt market town of Bradford on Avon offers a mix of delightful shops, restaurants, hotels and bed and breakfasts lining the narrow streets, not to mention a weekly market on Thursdays (8am-4pm). Still a natural focus at the centre of the town, the ancient bridge retains two of its 13th century arches and offers a fabulous view of the hillside above the town - dotted with the old weavers' cottages – and the river bank flanked by 19th century former cloth mills. Calne Calne evolved during the 18th and 19th centuries with the wool industry. Blending the old with the new, much of the original Calne is located along the River Marden where some of the historic buildings still remain. There is also the recently restored Castlefields Park with nature trails and cycle path easily accessible from the town centre. Castle Combe Set within the stunning Wiltshire Cotswolds, Castle Combe is a classically quaint English village. Often referred to as the ‘prettiest village in England’, it has even been featured regularly on the big screen – most recently in Hollywood blockbuster ‘The Wolfman’ and Stephen Spielberg’s ‘War Horse’. -

English Tourism Factsheet

English Tourism factsheet An annual celebration of English tourism, English Tourism Week will take place from 22-31 May to highlight the importance, value and vast contribution the sector makes to the UK economy. We are honoured to have the patronage of HRH The Prince of Wales. Although the COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating impact on tourism in the UK and worldwide, continuing to affect both the domestic and international sectors, in 2019, tourism was one of England’s largest and most valuable industries. • £100.8bn was spent on tourism in England in 2019. This included 99m overnight domestic trips, 1.4bn domestic day trips and 36.1m inbound trips. • Pre-pandemic the industry supported 2.6m jobs in England. • Domestic tourism spend for Britain will reach just 67% of 2019 levels. • English destinations are a huge draw for overseas visits – in the first nine months of 2019 there were a record 12.6 million visits to English regions outside London. International visitors spent £6.25 billion across England’s regions during this period. • Domestic tourism in England is also driving growth and supporting jobs. In the first 11 months of 2019 there were 43 million domestic holiday trips in England, with these holidaymakers spending over £10 billion in the same period • Tourism delivers economic growth in every city, local authority, and region, benefitting local communities and the wider economy. Get involved in English Tourism Week The slogan this year is “Here for Tourism”. Visit EnglishTourismWeek.org to download the toolkit of assets to help you brand your activities and show you are here for tourism. -

Follyfields, Yatton Keynell, Chippenham, SN14

Follyfields, Yatton Keynell, Chippenham, SN14 7JS Detached Bungalow Ample scope for improving 4 Bedrooms 2 Receptions Fitted Kitchen Double Garage 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH Good Size Garden with views James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Sought after village Approximately 1,251 sq ft Price Guide: £380,000 ‘Situated on the edge of this highly sought after village yet within walking distance to amenities, a detached bungalow with ample scope for improving and extending’ The Property The property is set within a good sized only 4 miles away for a further range of Local Authority plot, approached through metal double facilities, and both Bath and Bristol are Follyfields is a detached bungalow situated gates and has ample private parking to the within a 30 minutes' drive. There are Wiltshire Council on the edge of the highly sought after front plus a double garage with power and frequent inter-city train services at village of Yatton Keynell within level storage over. The garden is arranged to the Chippenham and the M4 (Junction 18) is Council Tax Band walking distance to many amenities. The rear laid mostly to lawn with a large patio about 5 minutes' drive away providing property was built over 30 years ago by the and mature shrubs, and enjoys views across access to London, the south and the F £2,465 current owners constructed of stone with open pasture land. Midlands. rendered elevations under a tiled roof, and today offers ample scope for general Situation Directions updating and extending with a large attic providing potential for conversion to Yatton Keynell is an excellent and sought- From Chippenham, follow the A420 accommodation subject to planning.