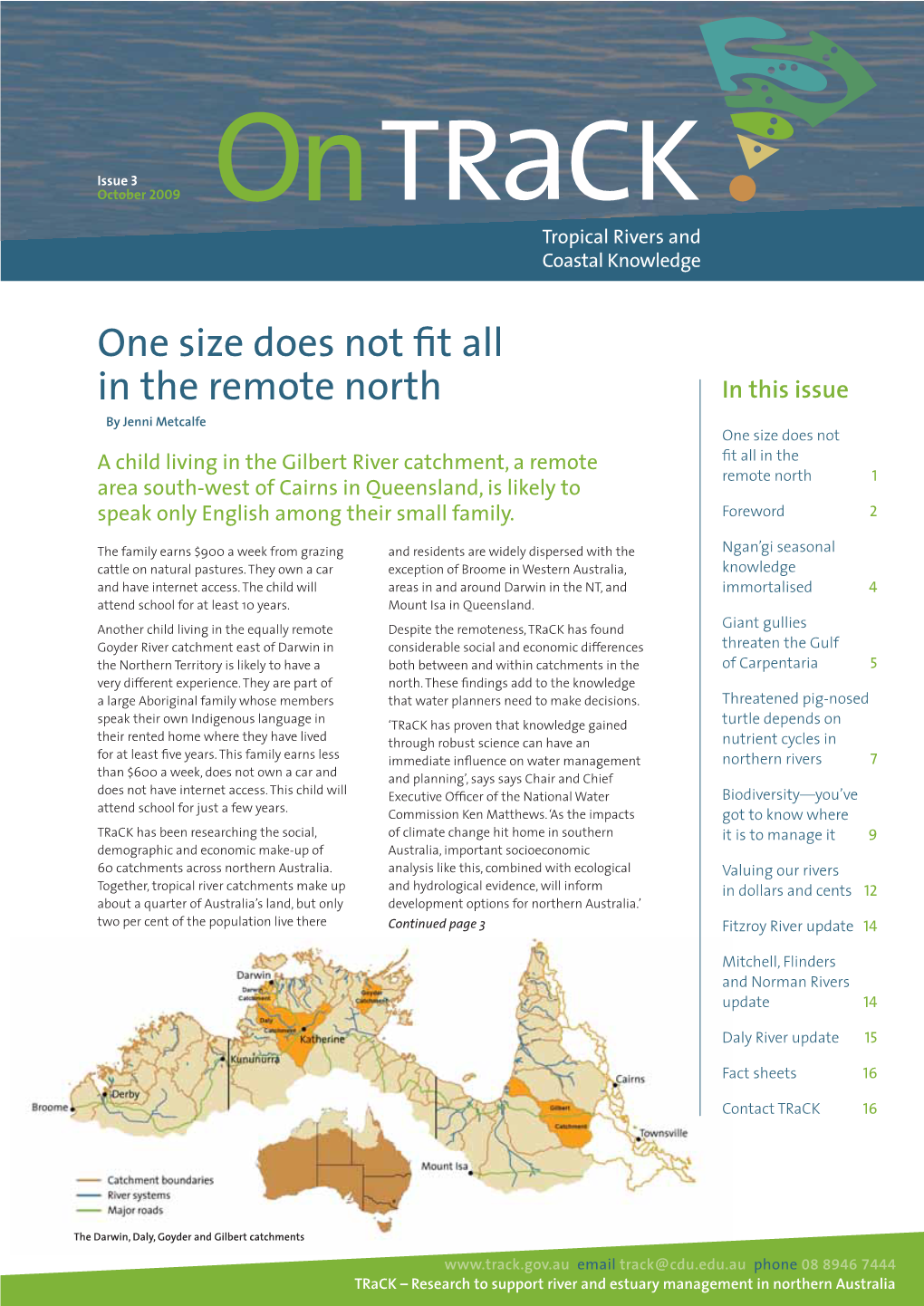

One Size Does Not Fit All in the Remote North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of a Voyage Around Arnhem Land in 1875

JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE AROUND ARNHEM LAND IN 1875 C.C. Macknight The journal published here describes a voyage from Palmerston (Darwin) to Blue Mud Bay on the western shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and back again, undertaken between September and December 1875. In itself, the expedition is of only passing interest, but the journal is worth publishing for its many references to Aborigines, and especially for the picture that emerges of the results of contact with Macassan trepangers along this extensive stretch of coast. Better than any other early source, it illustrates the highly variable conditions of communication and conflict between the several groups of people in the area. Some Aborigines were accustomed to travelling and working with Macassans and, as the author notes towards the end of his account, Aboriginal culture and society were extensively influenced by this contact. He also comments on situations of conflict.1 Relations with Europeans and other Aborigines were similarly complicated and uncertain, as appears in several instances. Nineteenth century accounts of the eastern parts of Arnhem Land, in particular, are few enough anyway to give another value. Flinders in 1802-03 had confirmed the general indications of the coast available from earlier Dutch voyages and provided a chart of sufficient accuracy for general navigation, but his contact with Aborigines was relatively slight and rather unhappy. Phillip Parker King continued Flinders' charting westwards from about Elcho Island in 1818-19. The three early British settlements, Fort Dundas on Melville Island (1824-29), Fort Wellington in Raffles Bay (1827-29) and Victoria in Port Essington (1838-49), were all in locations surveyed by King and neither the settlement garrisons nor the several hydrographic expeditions that called had any contact with eastern Arnhem Land, except indirectly by way of the Macassans. -

A New Freshwater Catfish (Pisces: Ariidae) from Northern Australia

Rec. West. Aust. Mus. 1988,14(1): 73-89 A new freshwater catfish (Pisces: Ariidae) from northern Australia PatriciaJ. Kailola* and Bryan E. Pierce* Abstract A new species of fork-tailed catfish is described on the basis of 31 specimens collected in northern Australia between the Fitzroy River (Western Australia) and the Mitchell River (Queensland). Arius midgleyi sp. novo grows to at least 1.3 m TL and is distinguished from other Australo-Papuan ariids by a combination of charac ters including snout shape, barbel length, eye size, tooth arrangement and gill raker number and position. Comparison is made with other ariid species occurring in northern Australian rivers, including the morphologically similar A. leptaspis (Bleeker). Introduction The Timor Sea and Gulf of Carpentaria drainage systems (Lake 1971) approx imately represent the Leichhardtian zoogeographic region of Whitley (1947). The rainfall pattern in this region is dominated by the wet monsoon (occurring within the period November to April). Most rivers here traverse a flat coastal plain about 15 km wide before reaching the sea (Lake 1971). These rivers commonly possess wide flood plains and low gradients, often contracting to a chain of waterholes during the dry season; some (Gregory River; Fitzroy to Daly Rivers) have reaches of rapids or very deep gorges. The average annual discharge from this region is 69000 billion litres (Lake 1971), most of it occurring during the wet season. Five of Australia's 18 species of fork-tailed catfishes (Ariidae) are common in this northern region, yet were overlooked by Whitley (1947) and Iredale and Whitley (1938). The members of this family, which is distributed circumglobally in the tropics and subtropics, may inhabit the sea, rivers within tidal influence, or fresh waters. -

Journal of J. G. Macdonald on an Expedition from Port Denison to The

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

Water Resources

Proposed Katherine to Gove Gas Pipeline Draft Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 7 Water Resources Contents 7 Water Resources ........................................................................................................................ 1 7.1 Description ................................................................................................................................... 1 7.1.1 Existing surface water resources .................................................................................... 1 7.1.2 Existing groundwater resources ...................................................................................... 3 7.2 Potential impacts of construction and operation .......................................................................... 7 7.2.1 Water extraction .............................................................................................................. 7 7.2.2 Physical changes to watercourses (including increased sedimentation) ...................... 11 7.2.3 Potential chemical contamination .................................................................................. 16 7.3 Mitigation responses and assessment of potential impacts ....................................................... 18 7.3.1 Environmental Management Plans ............................................................................... 18 7.4 Summary – predicted environmental outcomes ......................................................................... 19 Figures Figure 7-1: Surface water management areas -

Gapuwiyak Local Implementation Plan

LOCAL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN GAPUWIYAK The Lake Evella Story In the Dreamtime two men, Girrgirrwanga and Gurrulan, cut a large hollow tree for a Djalubu, a coffin, in preparation for a burial ceremony. The Djalubu was placed upright in the ground on the south west edge of the current lake. A cormorant of the Dhalwangu clan flew from Gan Gan towards Gapuwiayk and when it approached, its wings hit the water and turned it into a big lake. Gapuwiyak is the traditional land of the Gupapuyngu Liyalanimirr clan. © Commonwealth of Australia 2010 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney-General’s Department. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration. Attorney-General’s Department, Central Office, 3-5 National Circuit, Canberra ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca. Please be aware that this report may contain the images and names of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have passed away. Design by Sprout SIGNATORY PAGE We will all work together to Close the Gap. DAVE CHALMERS AO CSC NT STATE MANAGER Through respect and collaboration DEPARTMENT OF FAMILIES, HOUSING, COMMUNITY SERVICES AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS we will create a better future for all of our children. This Local Implementation Plan is our THE HON MALARNDIRRI MCCarthY, MLA Northern Territory MINISTER FOR INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT commitment to create a long lasting partnership between the people of Gapuwiyak and governments. -

Mackay Expedition to Arnhem Land, 1928

Mackay expedition to Arnhem Land, 1928 Once more the lure of ‘unexplored’ country and provided ‘much information’ on the country in prospects for pastoral and agricultural expansion Arnhem Land. It was probably Rogers who advised were the impetus for Donald Mackay’s Arnhem Land them against taking the buggy any further than Roper expedition in 1928. Again, Herbert Basedow and Bar. As Lovell had been hired to drive the buggy, his Frank Feast joined Mackay, along with Walter Sully, a services were no longer required and he departed. cinematographer, and CW Lovell, who was responsible On 5 May the party crossed the Roper River and for stores and equipment. They departed Sydney on headed north to the Wilton River, which it followed 3 April on the SS Marella, stopping at Brisbane where for several days. After passing Mount Marumba, they purchased a buggy, and arrived in Darwin on the expedition made for the Goyder River, passing 14 April. Two days later the party caught the train through low hills and eucalypt forests with occasional south to Katherine, where they took delivery of 26 paperbark thickets. Some time after crossing the horses and 6 mules, and Larry Coonan was engaged Goyder a hill was climbed to examine the lie of the to look after them. Two Aboriginal men, Barney and land. They decided to turn north-west. Prior to Deacon, were also hired to assist. Mackay’s expedition, only a few exploring parties had Basedow found the horses and mules initially travelled through the region, so a comprehensive problematic, noting ‘some exciting scenes when map was not available. -

Flood Watch Areas Arnhem Coastal Rivers Northern Territory River Basin No

Flood Watch Areas Arnhem Coastal Rivers Northern Territory River Basin No. Blyth River 15 Buckingham River 17 East Alligator River 12 Goomadeer River 13 A r a f u r a S e a Goyder River 16 North West Coastal Rivers Liverpool River 14 T i m o r S e a River Basin No. Adelaide River 4 below Adelaide River Town Arnhem Croker Coastal Daly River above Douglas River 10 Melville Island Rivers Finniss River 2 Island Marchinbar Katherine River 11 Milikapiti ! Island Lower Daly River 9 1 Elcho ! Carpentaria Coastal Rivers Mary River 5 1 Island Bathurst Nguiu Maningrida Galiwinku River Basin No. Island 12 ! ! Moyle River 8 ! Nhulunbuy 13 Milingimbi ! Yirrkala ! Calvert River 31 South Alligator River 7 DARWIN ! ! Howard " Oenpelli Ramingining Groote Eylandt 23 Tiwi Islands 1 2 Island 17 North West 6 ! 14 Koolatong River 21 Jabiru Upper Adelaide River 3 Coastal 15 Batchelor 4 Limmen Bight River 27 Wildman River 6 Rivers ! 16 7 21 McArthur River 29 3 5 ! Bickerton Robinson River 30 Island Daly River ! Groote Roper River 25 ! ! Bonaparte Coastal Rivers Bonaparte 22 Alyangula Eylandt Rosie River 28 Pine 11 ! 9 Creek Angurugu River Basin No. Coastal 8 Towns River 26 ! ! Kalumburu Rivers Numbulwar Fitzmaurice River 18 ! Walker River 22 Katherine 25 Upper Victoria River 20 24 Ngukurr 23 Waterhouse River 24 18 ! Victoria River below Kalkarindji 19 10 Carpentaria G u l f 26 Coastal Rivers ! o f ! Wyndham Vanderlin C a r p e n t a r i a ! 28 Kununurra West Island Island 27 ! Borroloola 41 Mount 19 Barnett Mornington ! ! Dunmarra Island Warmun 30 (Turkey 32 Creek) ! 29 Bentinck 39 Island Kalkarindji 31 ! Elliott ! ! Karumba ! 20 ! Normanton Doomadgee Burketown Fitzroy ! Crossing Renner ! Halls Creek ! Springs ! ! Lajamanu 41 Larrawa ! Warrego Barkly ! 40 33 Homestead QLD ! Roadhouse Tennant ! Balgo Creek WA ! Hill Camooweal ! 34 Mount Isa Cloncurry ! ! ! Flood Watch Area No. -

Flood Risk Management in Australia Building Flood Resilience in a Changing Climate

Flood Risk Management in Australia Building flood resilience in a changing climate December 2020 Flood Risk Management in Australia Building flood resilience in a changing climate Neil Dufty, Molino Stewart Pty Ltd Andrew Dyer, IAG Maryam Golnaraghi (lead investigator of the flood risk management report series and coordinating author), The Geneva Association Flood Risk Management in Australia 1 The Geneva Association The Geneva Association was created in 1973 and is the only global association of insurance companies; our members are insurance and reinsurance Chief Executive Officers (CEOs). Based on rigorous research conducted in collaboration with our members, academic institutions and multilateral organisations, our mission is to identify and investigate key trends that are likely to shape or impact the insurance industry in the future, highlighting what is at stake for the industry; develop recommendations for the industry and for policymakers; provide a platform to our members, policymakers, academics, multilateral and non-governmental organisations to discuss these trends and recommendations; reach out to global opinion leaders and influential organisations to highlight the positive contributions of insurance to better understanding risks and to building resilient and prosperous economies and societies, and thus a more sustainable world. The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics Talstrasse 70, CH-8001 Zurich Email: [email protected] | Tel: +41 44 200 49 00 | Fax: +41 44 200 49 99 Photo credits: Cover page—Markus Gebauer / Shutterstock.com December 2020 Flood Risk Management in Australia © The Geneva Association Published by The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics, Zurich. 2 www.genevaassociation.org Contents 1. -

Freshwater Fish and Aquatic Habitat Survey of Cape York Peninsula

CAPE YORK PENINSULA NATURAL RESOURCES ANALYSIS PROGRAM (NRAP) FRESHWATER FISH AND AQUATIC HABITAT SURVEY OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA B. W. Herbert, J.A. Peeters, P.A. Graham and A.E. Hogan Freshwater Fisheries and Aquaculture Centre Queensland Department of Primary Industries 1995 CYPLUS is a joint initiative of the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY (CYPLUS) Natural Resources Analysis Program FRESHWATER FISH AND AQUATIC HABITAT SURVEY OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA B. W. Herbert, J. A. Peeters, P.A. Graham and A.E. Hogan Freshwater Fisheries and Aquaculture Centre Queensland Department of Primary Industries 1995 CYPLUS is a joint initiative of the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments Final report on project: NRlO - FISH FAUNA SURVEY Recommended citation: Herbert, B.W., Peeters, J.A., Graham, P.A. and Hogan, A.E. (1995). 'Freshwater Fish and Aquatic Habitat Survey of Cape York Peninsula'. (Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy, Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland, Brisbane, Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories, Canberra, Queensland Department of Primary Industries, Brisbane.) Note: Due to the timing of publication, reports on other CYPLUS projects may not be fully cited in the REFERENCES section. However, they should be able to be located by author, agency or subject. ISBN 0 7242 6204 0 The State of Queensland and Commonwealth of Australia 1995. Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any means without the prior written permission of the Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland and the Australian Government Publishing Service. -

Supplementary Material Mitochondrial DNA Analyses of the Saltwater

10.1071/ZO12008_AC CSIRO 2012 Australian Journal of Zoology 2012, 60(1), 18-25 Supplementary Material Mitochondrial DNA analyses of the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) from the Northern Territory of Australia Naomi L. Luck1, Kristen C. Thomas1, Victoria E. Morin-Adeline1, Sophie Barwick1, Amanda Y. Chong1, Eliza L. Carpenter1, LinXiao Wan1, Cali E. Willet1, Shannan M. Langford- Salisbury1, Mary Abdelsayd1, Rachel A. Ang1, Sarah J. Atkinson1, Fabian G. Barcelo1, Melanie E. Booth1, Emma J. Bradbury1, Thomas L. Branighan1, Jennifer Brown1, Lesley E. Castillo1, Nichola D. Chandler1, Josephine Y. Chong1, Kimberly J. Collits1, Emma Cook1, Rachel E. Cruz1, Claire A. Farrugia1, Jessica L. Fletcher1, Sophie Fletcher1, Nicole S. Gamaliel1, Jessica F. Gurr1, Nathan J. Hallett1, Grace Hargreaves1, Teresa Harris1, Samantha Hollings1, Ryan L. Hopcroft1, Danielle Johinke1, Pippa L. Kern1, Jane L. Kiddell1, Kristen E. Kilby1, Borjana Kragic1, Jacqueline H. Kwan1, Joseph I. Lee1, Jennifer M. Liang1, Mette C. Lillie1, Belle C. Lui1, Sharon W. Luk1, Kwok H. Lun1, Kate L. Marshall1, Jolanta A. Marzec1, Kellie T. Masters1, Laura J. Mazurkijevic1, Jeremy Medlock1, Christopher Meoli1, Katrina M. Morris1,Yvonne H. Noh1, Hana Okazaki1, Tamara J. Orourke1, Elyssa M. Payne1, Dean J. Powell1, Antonia R. Quinlivan1, Thomas J. Reeves1, Kate L. Robson 1, Leah J. Royle1, Ryan Stevenson 1, Teigan Sellens1, ZiChen Sun1, Amanda L. Sutton1, Amelia Swan1, Jason M. Tang1, Jarrod E. Tinker1, Suzanne C. Tomlinson1, Tessa Wilkin1, Amanda L. Wright1, Sam 1 1 1 2 2,3 T. Xiao , Jessica Yang , Christine Yee , Weerachai Jaratlerdsiri , Sally R. Isberg , Lee Miles2, Damien Higgins2, Amanda Lane2, Jaime Gongora2* 1 1 Undergraduate student, Bachelor of Animal and Veterinary Bioscience, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney. -

A Compendium of Ecological Information on Australia's Northern

A Compendium of Ecological Information on Australia’s Northern Tropical Rivers REPORT 7 Freshwater Fish Damien BurrowsA AAustralian Centre for Tropical Freshwater Research, James Cook University, Townsville Queensland 4811 Australia Authors This report should be cited as follows: Burrows, D. 2008. In G.P. Lukacs and C.M. Finlayson (eds) 2008. A Compendium of Ecological Information on Australia’s Northern Tropical Rivers. Sub-project 1 of Australia’s Tropical Rivers – an integrated data assessment and analysis (DET18). A report to Land & Water Australia. National Centre for Tropical Wetland Research, Townsville, Queensland. Contact information NCTWR C/ Australian Centre for Tropical Freshwater Research James Cook University Townsville 4811 Queensland Australia Funding statement This project was funded by the Natural Heritage Trust Phase 2 (NHT2) and Land & Water Australia (LWA) as part of the Tropical Rivers Inventory and Assessment Project (TRIAP). Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the National Centre for Tropical Wetlands Research and its partners. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this report are factually correct, some essential data rely on the references cited and the NCTWR do not accept responsibility for the accuracy, currency or completeness of the contents of this report, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the report. Readers should exercise -

WATER RESOURCES of EAST ARNHEM LAND 660000Me Mort Point

680000mECape Wessel 700000mE (Rimbija Island) Low Point 8780000mN WATER RESOURCES OF EAST ARNHEM LAND 660000mE Mort Point Auster Point GROUNDWATER FEATURES: GENERAL FEATURES kilometres 0 2 4 6 8 10 20 30 40 kilometres Groundwater boundary Homeland name BLACK NUMBERED LINES ARE 10000 METRE INTERVALS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MAP GRID, ZONE 53 Bore Country name PROJECTION : UNIVERSAL TRANSVERSE MERCATOR Small spring, discharge up to 10 L/s Place name HORIZONTAL DATUM : AUSTRALIAN GEODETIC DATUM 1966 Stream gauging station - open, closed Jensen Bay GS 8260134 Stream gauging station number Sphink Head Widespread aquifer of poorly consolidated sandstone in the north-east and south; Rainfall station - open, closed limestone in the west and vuggy sandstone on Groote Eylandt. (Gedge Point) Large quantities of groundwater exist, sufficient for irrigation and industrial purposes. Rainfall station number Bore yields typically more than 10 L/s with a maximum of 50 L/s. R 8260053 operated by Water Resources Division 8760000mN High success rate expected. This aquifer provides the base flow for the major streams. Rainfall station number 640000mE (Marchinbar Island) YIRRKALA ANNUAL RAINFALL DR 014502 operated by Bureau of Meteorology 2500 Rainforest (may indicate groundwater discharge) Local aquifers in sand and fractured sandstone, siltstone, dolomite and volcanic rocks. 6 YEAR MOVING AVERAGE Stock and domestic quanities of groundwater are available at selected sites. Road 2000 Bore yields typically range from 0.5 to 5.0 L/s. Moderate success rate expected. Vehicle track (Red Point) Landing ground 1500 Narrow zones of high yielding sand aquifers occuring as valley infill in the north-east; Landing ground - disused thin, lateritised sandstone occurring across a dissected plateau, inthe north-west and Lagoon Bay hard sedimentary rocks and poorly consolidated sandstone in the south.