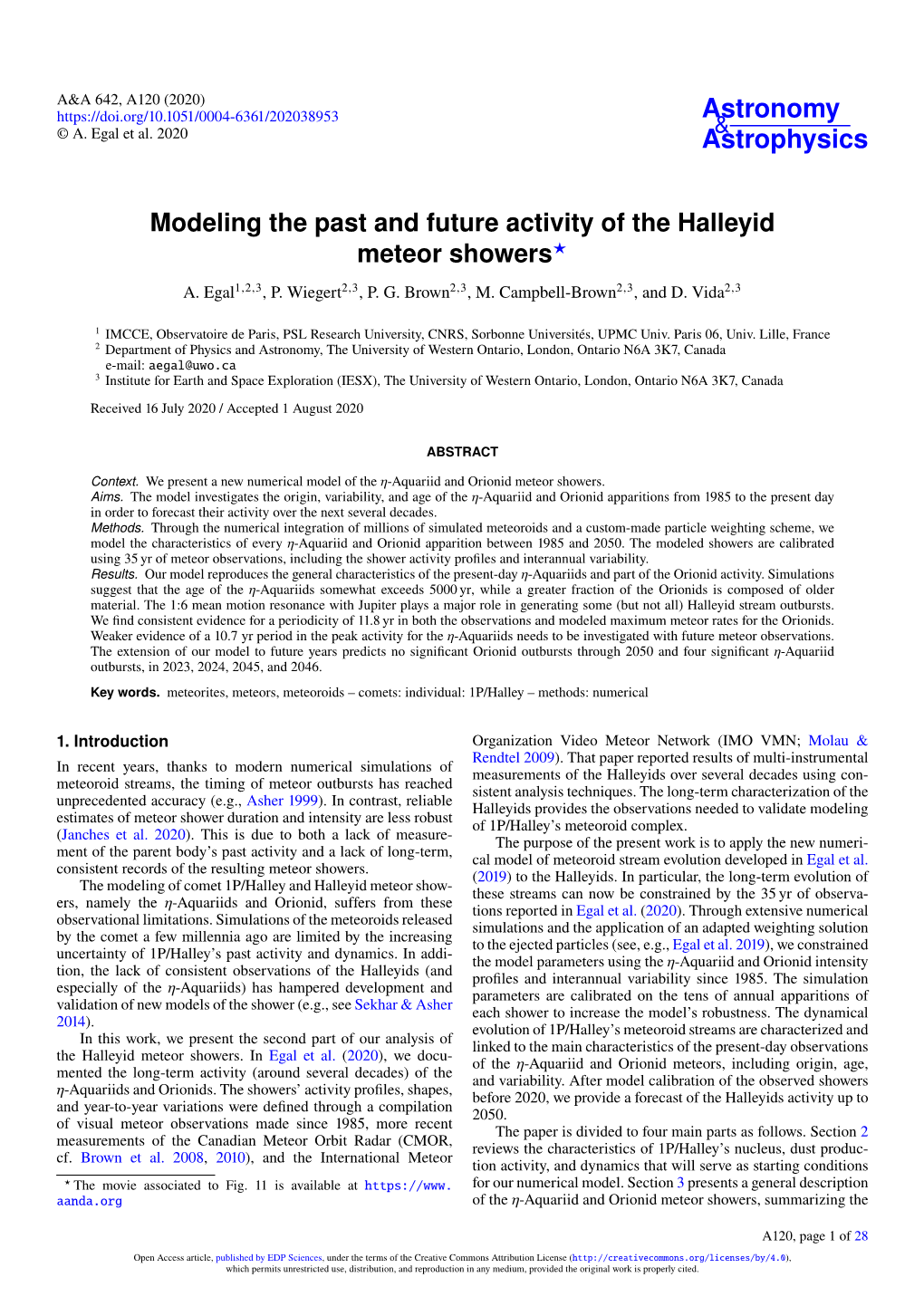

Modeling the Past and Future Activity of the Halleyid Meteor Showers? A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This Article in PDF Format

A&A 598, A40 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201629659 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics Separation and confirmation of showers? L. Neslušan1 and M. Hajduková, Jr.2 1 Astronomical Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, 05960 Tatranska Lomnica, Slovak Republic e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomical Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dubravska cesta 9, 84504 Bratislava, Slovak Republic e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 September 2016 / Accepted 30 October 2016 ABSTRACT Aims. Using IAU MDC photographic, IAU MDC CAMS video, SonotaCo video, and EDMOND video databases, we aim to separate all provable annual meteor showers from each of these databases. We intend to reveal the problems inherent in this procedure and answer the question whether the databases are complete and the methods of separation used are reliable. We aim to evaluate the statistical significance of each separated shower. In this respect, we intend to give a list of reliably separated showers rather than a list of the maximum possible number of showers. Methods. To separate the showers, we simultaneously used two methods. The use of two methods enables us to compare their results, and this can indicate the reliability of the methods. To evaluate the statistical significance, we suggest a new method based on the ideas of the break-point method. Results. We give a compilation of the showers from all four databases using both methods. Using the first (second) method, we separated 107 (133) showers, which are in at least one of the databases used. These relatively low numbers are a consequence of discarding any candidate shower with a poor statistical significance. -

In Situ Observations of Cometary Nuclei 211

Keller et al.: In Situ Observations of Cometary Nuclei 211 In Situ Observations of Cometary Nuclei H. U. Keller Max-Planck-Institut für Aeronomie D. Britt University of Central Florida B. J. Buratti Jet Propulsion Laboratory N. Thomas Max-Planck-Institut für Aeronomie (now at University of Bern) It is only through close spacecraft encounters that cometary nuclei can be resolved and their properties determined with complete confidence. At the time of writing, only two nuclei (those of Comets 1P/Halley and 19P/Borrelly) have been observed, both by rapid flyby missions. The camera systems onboard these missions have revealed single, solid, dark, lumpy, and elongated nuclei. The infrared systems gave surface temperatures well above the free sublimation tempera- ture of water ice and close to blackbody temperatures. The observed nuclei were much more similar than they were different. In both cases, significant topography was evident, possibly reflecting the objects’ sublimation histories. Dust emission was restricted to active regions and jets in the inner comae were prevalent. Active regions may have been slightly brighter than inert areas but the reflectance was still very low. No activity from the nightside was found. In this chapter, the observations are presented and comparisons are made between Comets Halley and Borrelly. A paradigm for the structure of cometary nuclei is also described that implies that the nonvolatile component defines the characteristics of nuclei and that high porosity, large- scale inhomogeneity, and moderate tensile strength are common features. 1. INTRODUCTION It is important to emphasize that prior to the spacecraft encounters with Comet 1P/Halley in 1986, the existence of The nuclei of most comets are too small to be resolved a nucleus was merely inferred from coarse observations. -

17. a Working List of Meteor Streams

PRECEDING PAGE BLANK NOT FILMED. 17. A Working List of Meteor Streams ALLAN F. COOK Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Cambridge, Massachusetts HIS WORKING LIST which starts on the next is convinced do exist. It is perhaps still too corn- page has been compiled from the following prehensive in that there arc six streams with sources: activity near the threshold of detection by pho- tography not related to any known comet and (1) A selection by myself (Cook, 1973) from not sho_m to be active for as long as a decade. a list by Lindblad (1971a), which he found Unless activity can be confirmed in earlier or from a computer search among 2401 orbits of later years or unless an associated comet ap- meteors photographed by the Harvard Super- pears, these streams should probably be dropped Sehmidt cameras in New Mexico (McCrosky and from a later version of this list. The author will Posen, 1961) be much more receptive to suggestions for dele- (2) Five additional radiants found by tions from this list than he will be to suggestions McCrosky and Posen (1959) by a visual search for additions I;o it. Clear evidence that the thresh- among the radiants and velocities of the same old for visual detection of a stream has been 2401 meteors passed (as in the case of the June Lyrids) should (3) A further visual search among these qualify it for permanent inclusion. radiants and velocities by Cook, Lindblad, A comment on the matching sets of orbits is Marsden, McCrosky, and Posen (1973) in order. It is the directions of perihelion that (4) A computer search -

Abstract Book

\ Abstract Book 50th ESLAB Symposium: “From Giotto to Rosetta” 14 – 18 March 2016 Leiden, The Netherlands 2 Table of Contents Programme .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Monday 14 March 2016 ............................................................................................................................ 5 Tuesday 15 March 2016 ............................................................................................................................ 7 Wednesday 16 March 2016 ...................................................................................................................... 9 Thursday 17 March 2016 ........................................................................................................................ 11 Friday 18 March 2016 ............................................................................................................................. 13 Poster Sessions........................................................................................................................................ 14 Abstracts .................................................................................................................................................... 23 Oral Presentations ............................................................................................................................... 23 Posters .................................................................................................................................................. -

Meteor Showers # 11.Pptx

20-05-31 Meteor Showers Adolf Vollmy Sources of Meteors • Comets • Asteroids • Reentering debris C/2019 Y4 Atlas Brett Hardy 1 20-05-31 Terminology • Meteoroid • Meteor • Meteorite • Fireball • Bolide • Sporadic • Meteor Shower • Meteor Storm Meteors in Our Atmosphere • Mesosphere • Atmospheric heating • Radiant • Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) 2 20-05-31 Equipment Lounge chair Blanket or sleeping bag Hot beverage Bug repellant - ThermaCELL Camera & tripod Tracking Viewing Considerations • Preparation ! Locate constellation ! Take a nap and set alarm ! Practice photography • Location: dark & unobstructed • Time: midnight to dawn https://earthsky.org/astronomy- essentials/earthskys-meteor-shower- guide https://www.amsmeteors.org/meteor- showers/meteor-shower-calendar/ • Where to look: 50° up & 45-60° from radiant • Challenges: fatigue, cold, insects, Moon • Recording observations ! Sky map, pen, red light & clipboard ! Time, position & location ! Recording device & time piece • Binoculars Getty 3 20-05-31 Meteor Showers • 112 confirmed meteor showers • 695 awaiting confirmation • Naming Convention ! C/2019 Y4 (Atlas) ! (3200) Phaethon June Tau Herculids (m) Parent body: 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann Peak: June 2 – ZHR = 3 Slow moving – 15 km/s Moon: Waning Gibbous June Bootids (m) Parent body: 7p/Pons-Winnecke Peak: June 27– ZHR = variable Slow moving – 14 km/s Moon: Waxing Crescent Perseid by Brian Colville 4 20-05-31 July Delta Aquarids Parent body: 96P/Machholz Peak: July 28 – ZHR = 20 Intermediate moving – 41 km/s Moon: Waxing Gibbous Alpha -

1950 Da, 205, 269 1979 Va, 230 1991 Ry16, 183 1992 Kd, 61 1992

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09684-4 — Asteroids Thomas H. Burbine Index More Information 356 Index 1950 DA, 205, 269 single scattering, 142, 143, 144, 145 1979 VA, 230 visual Bond, 7 1991 RY16, 183 visual geometric, 7, 27, 28, 163, 185, 189, 190, 1992 KD, 61 191, 192, 192, 253 1992 QB1, 233, 234 Alexandra, 59 1993 FW, 234 altitude, 49 1994 JR1, 239, 275 Alvarez, Luis, 258 1999 JU3, 61 Alvarez, Walter, 258 1999 RL95, 183 amino acid, 81 1999 RQ36, 61 ammonia, 223, 301 2000 DP107, 274, 304 amoeboid olivine aggregate, 83 2000 GD65, 205 Amor, 251 2001 QR322, 232 Amor group, 251 2003 EH1, 107 Anacostia, 179 2007 PA8, 207 Anand, Viswanathan, 62 2008 TC3, 264, 265 Angelina, 175 2010 JL88, 205 angrite, 87, 101, 110, 126, 168 2010 TK7, 231 Annefrank, 274, 275, 289 2011 QF99, 232 Antarctic Search for Meteorites (ANSMET), 71 2012 DA14, 108 Antarctica, 69–71 2012 VP113, 233, 244 aphelion, 30, 251 2013 TX68, 64 APL, 275, 292 2014 AA, 264, 265 Apohele group, 251 2014 RC, 205 Apollo, 179, 180, 251 Apollo group, 230, 251 absorption band, 135–6, 137–40, 145–50, Apollo mission, 129, 262, 299 163, 184 Apophis, 20, 269, 270 acapulcoite/ lodranite, 87, 90, 103, 110, 168, 285 Aquitania, 179 Achilles, 232 Arecibo Observatory, 206 achondrite, 84, 86, 116, 187 Aristarchus, 29 primitive, 84, 86, 103–4, 287 Asporina, 177 Adamcarolla, 62 asteroid chronology function, 262 Adeona family, 198 Asteroid Zoo, 54 Aeternitas, 177 Astraea, 53 Agnia family, 170, 198 Astronautica, 61 AKARI satellite, 192 Aten, 251 alabandite, 76, 101 Aten group, 251 Alauda family, 198 Atira, 251 albedo, 7, 21, 27, 185–6 Atira group, 251 Bond, 7, 8, 9, 28, 189 atmosphere, 1, 3, 8, 43, 66, 68, 265 geometric, 7 A- type, 163, 165, 167, 169, 170, 177–8, 192 356 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09684-4 — Asteroids Thomas H. -

Smithsonian Contributions Astrophysics

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS to ASTROPHYSICS Number 14 Discrete Levels off Beginning Height off Meteors in Streams By A. F. Cook Number 15 Yet Another Stream Search Among 2401 Photographic Meteors By A. F. Cook, B.-A. Lindblad, B. G. Marsden, R. E. McCrosky, and A. Posen Smithsonian Institution Astrophysical Observatory Smithsonian Institution Press SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ASTROPHYSICS NUMBER 14 A. F. cook Discrete Levels of Beginning Height of Meteors in Streams SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS CITY OF WASHINGTON 1973 Publications of the Smithsonian Institution Astrophysical Observatory This series, Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics, was inaugurated in 1956 to provide a proper communication for the results of research conducted at the Astrophysical Observatory of the Smithsonian Institution. Its purpose is the "increase and diffusion of knowledge" in the field of astrophysics, with particular emphasis on problems of the sun, the earth, and the solar system. Its pages are open to a limited number of papers by other investigators with whom we have common interests. Another series, Annals of the Astrophysical Observatory, was started in 1900 by the Observa- tory's first director, Samuel P. Langley, and was published about every ten years. These quarto volumes, some of which are still available, record the history of the Observatory's researches and activities. The last volume (vol. 7) appeared in 1954. Many technical papers and volumes emanating from the Astrophysical Observatory have appeared in the Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. Among these are Smithsonian Physical Tables, Smithsonian Meteorological Tables, and World Weather Records. Additional information concerning these publications can be obtained from the Smithsonian Institution Press, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. -

Backyard Astronomy Santa Fe Public Library

Backyard Astronomy Santa Fe Public Library Photo Credit: NASA, A Mess of Stars,08-10-2015 1. What will you need? 2. What am I looking at? 3. What you can See a. August 2020 b. September 2020 c. October 2020 4. Star Stories 5. Activities a. Tracking the Sunset/Sunrise b. Moon Watching c. Tracking the International Space Station d. Constellation Discovery 6. What to Read Backyard Astronomy Santa Fe Public Library What will you need? The most important things you will need are your curiosity, your naked eyes, and the ability to observe. You do not need fancy telescopes to begin enjoying the wonders of our amazing night skies. Here in Northern New Mexico, we are blessed with the ability to step out of our homes, look up, and see the Milky Way displayed above us without too much obstruction. Photo Credit: NASA, A Glimpse of the Milky Way, 12-13-2005 While the following Items can help you to begin exploring the wonders of the Universe, they are not required. These items include: 1. Binoculars 2. Telescope (a small inexpensive one is fine) 3. Star Chart Planisphere 4. Free Astronomy Apps for both iPhones and Androids There are several really good free apps that help you identify, locate, and track celestial objects. One that I use is Star Walk 2 but there are other good apps available. Backyard Astronomy Santa Fe Public Library What am I looking at? When you look up at night, what do you see? Probably more than you think! Below is a list of the Celestial Items you can see. -

Small Solar System Bodies As Granular Media D

Small Solar System Bodies as granular media D. Hestroffer, P. Sanchez, L Staron, A. Campo Bagatin, S. Eggl, W. Losert, N. Murdoch, E. Opsomer, F. Radjai, D. C. Richardson, et al. To cite this version: D. Hestroffer, P. Sanchez, L Staron, A. Campo Bagatin, S. Eggl, et al.. Small Solar System Bodiesas granular media. Astronomy and Astrophysics Review, Springer Verlag, 2019, 27 (1), 10.1007/s00159- 019-0117-5. hal-02342853 HAL Id: hal-02342853 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02342853 Submitted on 4 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Astron Astrophys Rev manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Small solar system bodies as granular media D. Hestroffer · P. S´anchez · L. Staron · A. Campo Bagatin · S. Eggl · W. Losert · N. Murdoch · E. Opsomer · F. Radjai · D. C. Richardson · M. Salazar · D. J. Scheeres · S. Schwartz · N. Taberlet · H. Yano Received: date / Accepted: date Made possible by the International Space Science Institute (ISSI, Bern) support to the inter- national team \Asteroids & Self Gravitating Bodies as Granular Systems" D. Hestroffer IMCCE, Paris Observatory, universit´ePSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Universit´e,Univ. -

HALLEY's COMET (Part II): Space Studies Vassili I. Moroz Space Research Institute Academy of Sciences of USSR Moscow 117810

HALLEY'S COMET (Part II): Space Studies Vassili I. Moroz Space Research Institute Academy of Sciences of USSR Moscow 117810, USSR ABSTRACT. An international armada of spacecraft encountered Comet Halley in March 1986. The present article gives a brief overview of this unique event during which a cometary nucleus was seen as a spatially resolved object for the first time. It is a very dark body, the shape is irregular and the structure is inhomogeneous; only the sunward side is active. Many parent molecules were identified in the coma, including complicated hydrocarbons. There was also organic matter in the comet dust particles. Extensive studies were made of the complicated plasma environment of the comet. 1. Cometary missions An impressive armada of spacecraft encountered Comet Halley in March 1986 (Fig. 1). The largest of them were Vega-1 and Vega-2. They had two goals: (1) studies of Venus by means of balloons and landers and (2) fly-by studies of Comet Halley. In June 1985 both spacecraft successfully delivered the landers and balloons at Venus, made a gravitational swing-by manoeuvre near this planet and were directed towards Comet Halley. The Vega mission was an international project. Although the spacecraft themselves were controlled by the Soviet Union, the scientific programme and the payloads were coordinated by the International Science and Technical Committee (CIST), representing scientific institutions in nine countries. Academician Sagdeev was the president of the CIST. Also the Giotto project was international. It was set up by the European Space Agency (ESA). Giotto was the first attempt of ESA to visit deep space. -

Analysis of Historical Meteor and Meteor Shower Records: Korea, China and Japan

Highlights of Astronomy, Volume 16 XXVIIIth IAU General Assembly, August 2012 c International Astronomical Union 2015 T. Montmerle, ed. doi:10.1017/S1743921314005079 Analysis of Historical Meteor and Meteor shower Records: Korea, China and Japan Hong-Jin Yang1, Changbom Park2 and Myeong-Gu Park3 1 Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, Korea email: [email protected] 2 Korea Institute for Advanced Study, Korea 3 Kyungpook National University, Korea Abstract. We have compiled and analyzed historical meter and meteor shower records in Ko- rean, Chinese, and Japanese chronicles. We have confirmed the peaks of Perseids and an excess due to the mixture of Orionids, north-Taurids, or Leonids through the Monte-Carlo test from the Korean records. The peaks persist for almostonethousandyears.Wehavealsoanalyzed seasonal variation of sporadic meteors from Korean records. Major features in Chinese meteor shower records are quite consistent with those of Korean records, particularly for the last millen- nium. Japanese records also show Perseids feature and Orionids/north-Taurids/Leonids feature, although they are less prominent compared to those of Korean or Chinese records. Keywords. meteors, meteor showers, historical records We have compiled and analyzed the meteor and meteor shower records in official Korean history books (Kim et al. 1145; Kim et al. 1451; Chunchugwan 1392-1863) dating from 57 B.C. to A.D. 1910, covering the Three Kingdoms period (from 57 B.C. to A.D. 918), Goryeo dynasty (from A.D. 918 to A.D. 1392), and Joseon dynasty (from A.D. 1392 to A.D. 1910). The books contain only a small number of meteor shower records in contrast to abundant meteor records. -

Occurrence and Altitude of the Non-Specular Long-Lived Meteor Trails During Meteor Showers at High Latitudes

EGU2020-1543 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-1543 EGU General Assembly 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Occurrence and altitude of the non-specular long-lived meteor trails during meteor showers at high latitudes Alexander Kozlovsky1, Renata Lukianova2, and Mark Lester3 1University of Oulu, Sodankyla Geophysical Observatory, Sodankyla, Finland ([email protected]) 2Space Research Institute, Moscow, Russia 3Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK Meteoroids entering the Earth’s atmosphere produce ionized trails, which are detectable by radio sounding. Majority of such radar detections are the echoes from cylindrical ionized trails, which occur if the radar beam is perpendicular to the trail, i.e., the reflection is specular. Typically such echoes detected by VHF radars last less than one second. However, sometimes meteor radars (MR) observe unusually long-lived meteor echoes and these echoes are non-specular (LLNS echoes). The LLNS echoes last up to several tens of seconds and show highly variable amplitude of the radar return. The LLNS echoes are received from the non-field-aligned irregularities of ionization generated along trails of bright meteors and it is believed that key role in their generation belongs to the aerosol particles arising due to fragmentation and burning of large meteoroids. The occurrence and height distributions of LLNS are studied using MR observations at Sodankylä Geophysical Observatory (SGO, 67° 22' N, 26° 38' E, Finland) during 2008-2019. Two parameters are analyzed: the percentage and height distribution of LLNS echoes. These LLNS echoes constitute about 2% of all MR detections.