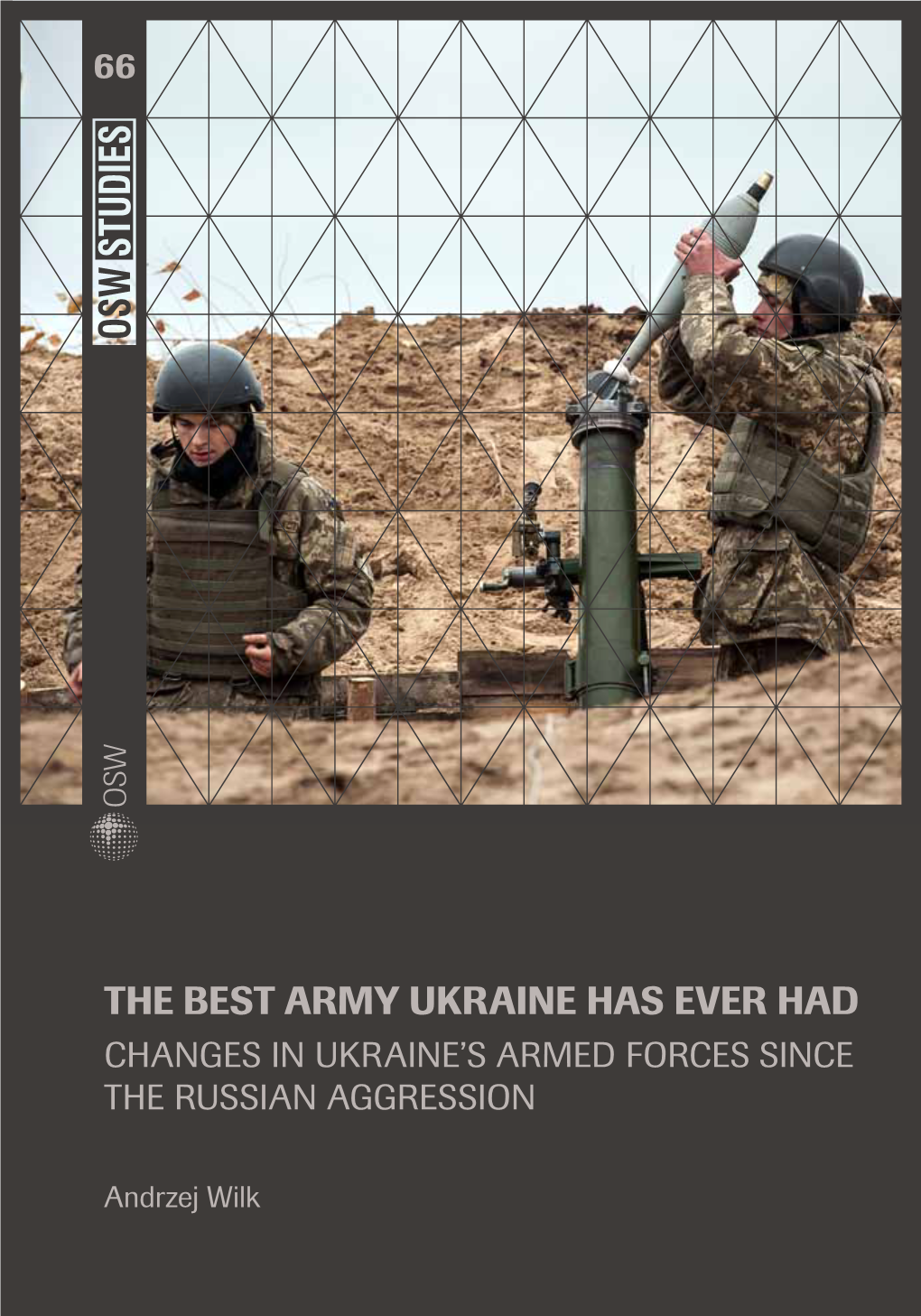

The Best Army Ukraine Has Ever Had Changes in Ukraine’S Armed Forces Since the Russian Aggression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dynamics of FM Frequencies Allotment for the Local Radio Broadcasting

DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING IN UKRAINE: 2015–2018 The Project of the National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine “Community Broadcasting” NATIONAL COUNCIL MINISTRY OF OF TELEVISION AND RADIO INFORMATION POLICY BROADCASTING OF UKRAINE OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING: 2015—2018 Overall indicators As of 14 December 2018 local radio stations local radio stations rate of increase in the launched terrestrial broadcast in 24 regions number of local radio broadcasting in 2015―2018 of Ukraine broadcasters in 2015―2018 The average volume of own broadcasting | 11 hours 15 minutes per 24 hours Type of activity of a TV and radio organization For profit radio stations share in the total number of local radio stations Non-profit (communal companies, community organizations) radio stations share in the total number of local radio stations NATIONAL COUNCIL MINISTRY OF OF TELEVISION AND RADIO INFORMATION POLICY BROADCASTING OF UKRAINE OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING: 2015—2018 The competitions held for available FM radio frequencies for local radio broadcasting competitions held by the National Council out of 97 FM frequencies were granted to the on consideration of which local radio stations broadcasters in 4 format competitions, were granted with FM frequencies participated strictly by local radio stations Number of granted Number of general Number of format Practical steps towards implementation of the FM frequencies competitions* competitions** “Community Broadcasting” project The -

JOURNAL O F E U R O P E a N E C O N O M Y Vol

58 JOURNAL O F E U R O P E A N E C O N O M Y Vol. 9 (№ 1). March 2010 Publication of Ternopil National Economic Universit y Macroeconomics Svitlana TSOHLA IMPROVEMENT OF THE QUALITY OF SERVICE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE HEALTH RESORT AND RECREATIONAL SECTOR OF UKRAINE Abstract The analysis of the satisfaction level of health resort rest is conducted. The «price-quality» econometric models for the rest homes and health resorts in order to define the service quality level for the health resort regions are devel- oped. The improvement trends of target-oriented development of resort and rec- reational sector are proved. Key words: Resort and recreational sector, satisfaction level, quality of service, price of services. JEL : Q26, O14. © Svitlana Tsohla, 2010. Tsohla Svitlana, Doctor of Science, Professor of Management and Marketing Department, Tavria National V. Vernadskyi University, Simferopol, Ukraine. J O U R N A L 59 OF EUROPEAN ECONOMY March 2010 General formulation of the problem and its connection with the important scientific or practical tasks The problem of quality assurance is universal in the modern world. The more successfully it is solved, the more effectually the any branch is developed. The concept of quality as a category, expressing the actual certainty of object concerning product is defined as a level of importance, the whole proper- ties of products, its possibilities to satisfy the certain social and personal needs. In accordance with the definition of International Organization for Stan- dardization, quality is the total of product properties and features, which makes it an ability to satisfy the conditional or envisaged needs. -

Promoting Civil Participation in Democratic Decision-Making

THE COE PROJECT ‘ PROMOTING CIVIL PARTICIPATION IN DEMOCRATIC OUR GOALS ARE TO HELP: DECISION-MAKING improve the legislation for effective civil participation IN UKRAINE ’ and civil society development; improve the mechanisms of WHO ARE WE? citizens and NGO impact on We are a Council of Europe project decision-making; that helps create an environment establish communication for stronger civil participation and between NGOs, citizens and citizen engagement in the decision- local authorities; making process at the local and national levels in accordance build up NGO capacity with the Council of Europe to advocate for changes and standards and international engage with public authorities best practices. in the decision-making process. WHAT HAVE WE ACHIEVED IN JUNE-AUGUST 2019? Conducted 2 workshops from the series of the Academy follow-up workshops “Civil participation: elements for strengthening the engagement between public authorities and community” – in partnership with the Kyiv City Council’s Centre for Public Communications and Information and Kyiv Civic Platform: • ‘Learn how to influence budget: finally, something else than participatory budgeting’ • ‘Public Spaces & Civic Engagement’ conducted a 4 day Summer Advocacy School: Doing analysis, facilitating and implementing changes with a view to enhancing advocacy and communi- cation competences of the activists in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts, where we: • exchanged experience with the city council of Lviv and jointly studied the importance of participatory budgeting as an effective -

Odessa Intercultural Profile

City of Odessa Intercultural Profile This report is based upon the visit of the CoE expert team on 30 June & 1 July 2017, comprising Irena Guidikova, Kseniya Khovanova-Rubicondo and Phil Wood. It should ideally be read in parallel with the Council of Europe’s response to Odessa’s ICC Index Questionnaire but, at the time of writing, the completion of the Index by the City Council is still a work in progress. 1. Introduction Odessa (or Odesa in Ukrainian) is the third most populous city of Ukraine and a major tourism centre, seaport and transportation hub located on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. Odessa is also an administrative centre of the Odessa Oblast and has been a multiethnic city since its formation. The predecessor of Odessa, a small Tatar settlement, was founded in 1440 and originally named Hacıbey. After a period of Lithuanian control, it passed into the domain of the Ottoman Sultan in 1529 and remained in Ottoman hands until the Empire's defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1792. In 1794, the city of Odessa was founded by decree of the Empress Catherine the Great. From 1819 to 1858, Odessa was a free port, and then during the twentieth century it was the most important port of trade in the Soviet Union and a Soviet naval base and now holds the same prominence within Ukraine. During the 19th century, it was the fourth largest city of Imperial Russia, and its historical architecture has a style more Mediterranean than Russian, having been heavily influenced by French and Italian styles. -

The History of Ukraine Advisory Board

THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE ADVISORY BOARD John T. Alexander Professor of History and Russian and European Studies, University of Kansas Robert A. Divine George W. Littlefield Professor in American History Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin John V. Lombardi Professor of History, University of Florida THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE Paul Kubicek The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findling, Series Editors Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kubicek, Paul. The history of Ukraine / Paul Kubicek. p. cm. — (The Greenwood histories of the modern nations, ISSN 1096 –2095) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 – 0 –313 – 34920 –1 (alk. paper) 1. Ukraine —History. I. Title. DK508.51.K825 2008 947.7— dc22 2008026717 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2008 by Paul Kubicek All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008026717 ISBN: 978– 0– 313 – 34920 –1 ISSN: 1096 –2905 First published in 2008 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48 –1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright materials in this book, but in some instances this has proven impossible. -

EURASIA Russia Fielding Two New Self-Propelled

EURASIA Russia Fielding Two New Self-Propelled Mortar Systems OE Watch Commentary: The accompanying excerpted article from Rossiyskaya Gazeta discusses Russian plans to field two new self-propelled mortar systems that are intended to support motorized rifle, airborne, and alpine infantry battalions. The 2S42 Lotos self-propelled mortar consists of a 2A60 120mm turret-mounted mortar mounted on a BMD- 4M airborne fighting vehicle chassis. The 2S41 Drok self- propelled mortar consists of 82mm turret-mounted mortar mounted on a Tayfun armored personnel carrier chassis. Russia already has self-propelled mortar systems in the inventory, including the 2S4 Tyulpan 240mm self-propelled mortar and the 2S23 Nona-SVK 120-mm battalion self- propelled gun, which functions as a hybrid mortar, gun, and howitzer. End OE Watch Commentary (Bartles) Russian Missile Troops and Artillery Emblem. Source: Russian government, via Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Medium_emblem_of_the_Russian_Missile_Troops_and_ Artillery.svg, Public domain “New self-propelled mortars designed for the Russian army -- the 2S42 Lotos self-propelled artillery gun and the 2S41 Drok wheeled self-propelled piece... are destined for the inventories of motorized rifle, air assault, and alpine infantry battalions.” Source: Aleksey Petrov and Yegor Badyanov, “Выстрелил и скрылся: зачем нужны новые самоходки “Лотос” и “Дрок” (Fire and Take Cover: Why the Need for the New Self-Propelled ‘Lotos’ and ‘Drok’),” Rossiyskaya Gazeta Online, 22 July 2019. https://rg.ru/2019/07/22/ vystrelil-i-skrylsia-zachem-nuzhny-novye-samohodki-lotos-i-drok.html Fire and Take Cover: Why the Need for the New Self-Propelled Lotos and Drok As we know, mortars are utilized as the basic means of delivering suppressive fire against enemy manpower, destroying an adversary’s concealed artillery positions, and hitting his military hardware. -

The Jews of Ukraine and Moldova

CHAPTER ONE THE JEWS OF UKRAINE AND MOLDOVA by Professor Zvi Gitelman HISTORICAL BACKGROUND A hundred years ago, the Russian Empire contained the largest Jewish community in the world, numbering about 5 million people. More than 40 percent—2 million of them—lived in Ukraine SHIFTING SOVEREIGNTIES and Bessarabia (the latter territory was subsequently divided Nearly a thousand years ago, Moldova was populated by a between the present-day Ukraine and Moldova; here, for ease Romanian-speaking people, descended from Romans, who of discussion, we use the terms “Bessarabia” and “Moldova” intermarried with the indigenous Dacians. A principality was interchangeably). Some 1.8 million lived in Ukraine (west of established in the territory in the fourteenth century, but it the Dniepr River) and in Bessarabia, and 387,000 made their did not last long. Moldova then became a tributary state of homes in Ukraine (east of the Dniepr), including Crimea. the Ottoman Empire, which lost parts of it to the Russian Thousands of others lived in what was called Eastern Galicia— Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. now Western Ukraine. After the 1917 Russian Revolution, part of Moldova lay Today the Jewish population of those areas is much reduced, within the borders of Romania. Eventually part of it became due to the cumulative and devastating impacts of World War I, the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) of Moldavia, the 1917 Russian Revolution, World War II and the Holocaust, a unit within the larger Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. massive emigration since the 1970s, and a natural decrease In August 1940, as Eastern Europe was being carved up resulting from a very low birth rate and a high mortality rate. -

Contours and Consequences of the Lexical Divide in Ukrainian

Geoffrey Hull and Halyna Koscharsky1 Contours and Consequences of the Lexical Divide in Ukrainian When compared with its two large neighbours, Russian and Polish, the Ukrainian language presents a picture of striking internal variation. Not only are Ukrainian dialects more mutually divergent than those of Polish or of territorially more widespread Russian,2 but on the literary level the language has long been characterized by the existence of two variants of the standard which have never been perfectly harmonized, in spite of the efforts of nationalist writers for a century and a half. While Ukraine’s modern standard language is based on the eastern dialect of the Kyiv-Poltava-Kharkiv triangle, the literary Ukrainian cultivated by most of the diaspora communities continues to follow to a greater or lesser degree the norms of the Lviv koiné in 1 The authors would like to thank Dr Lance Eccles of Macquarie University for technical assistance in producing this paper. 2 De Bray (1969: 30-35) identifies three main groups of Russian dialects, but the differences are the result of internal evolutionary divergence rather than of external influences. The popular perception is that Russian has minimal dialectal variation compared with other major European languages. Maximilian Fourman (1943: viii), for instance, told students of Russian that the language ‘is amazingly uniform; the same language is spoken over the vast extent of the globe where the flag of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics flies; and you will be understood whether you are speaking to a peasant or a university professor. There are no dialects to bother you, although, of course, there are parts of the Soviet Union where Russian may be spoken rather differently, as, for instance, English is spoken differently by a Londoner, a Scot, a Welshman, an Irishman, or natives of Yorkshire or Cornwall. -

Kiev 1941: Hitler's Battle for Supremacy in the East

Kiev 1941 In just four weeks in the summer of 1941 the German Wehrmacht wrought unprecedented destruction on four Soviet armies, conquering central Ukraine and killing or capturing three-quarters of a million men. This was the battle of Kiev – one of the largest and most decisive battles of World War II and, for Hitler and Stalin, a battle of crucial importance. For the first time, David Stahel charts the battle’s dramatic course and after- math, uncovering the irreplaceable losses suffered by Germany’s ‘panzer groups’ despite their battlefield gains, and the implications of these losses for the German war effort. He illuminates the inner workings of the German army as well as the experiences of ordinary soldiers, showing that with the Russian winter looming and Soviet resistance still unbroken, victory came at huge cost and confirmed the turning point in Germany’s war in the east. David Stahel is an independent researcher based in Berlin. His previous publications include Operation Barbarossa and Germany’s Defeat in the East (Cambridge, 2009). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 210.212.129.125 on Sat Dec 22 18:00:30 WET 2012. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139034449 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2012 Kiev 1941 Hitler’s Battle for Supremacy in the East David Stahel Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 210.212.129.125 on Sat Dec 22 18:00:30 WET 2012. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139034449 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2012 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107014596 c David Stahel 2012 This publication is in copyright. -

Yaroslav KICHUK Tetyana SHEVCHUK PUBLIC

Yaroslav KICHUK Tetyana SHEVCHUK PUBLIC MOVEMENT OF THE NATIONAL MINORITIES IN BUDZHAK POLIETHNIC SOCIETY AS A FACTOR OF INTERCULTURAL INTERACTION (PERIOD OF INDEPENDENT UKRAINE) - Abstract - The article deals with the revival of civil society institutions, cultural activities of national minorities and people-to-people diplomacy of national and cultural public organizations in Budzhak – the Ukrainian region, located between the Dniester and the Danube deltas, bordering on Romania and Moldova. A significant increase in ethnic consciousness, as well as a sharp focus of regional communities on the preservation and development of their national languages and cultural traditions has been observed in the territory of the Budzhak frontier since the late 1980s. The imperative for the development of the Ukrainian post-imperial transformational society in Budzhak has been the synergy of activities of the Albanian, Bulgarian, Gagauze, German, Greek, Jew, Polish, Romanian (Moldovan), Russian, Ukrainian etc. national minorities with the purpose of developing their language and culture (traditions, rituals and beliefs, art and song, folk crafts) and preserving the cultural identity of their ethnic groups. To gain mutual understanding in interethnic relations, the representatives of national diasporas, together with the local educational establishments, take great pains to create optimal conditions for the development of all national minorities, pay enormous attention to educational activities aimed at raising the historical memory of the peoples of Budzhak, promote intercultural dialogue and tolerance as necessary prerequisites for living in multicultural society. Keywords: national minorities; development of local communities; civil society institutions; national and cultural public organizations; non- Izmail State University of Humanities, Ukraine ([email protected]), ORCID: 0000-0003- 0931-1211. -

ОГОЛОШЕННЯ Про Проведення Відкритих Торгів UA-2020-07-15-001374-A

ОГОЛОШЕННЯ про проведення відкритих торгів UA-2020-07-15-001374-a Найменування замовника: Державна установа "Місцеві дороги Херсонщини" Purchasing body: STATE INSTITUTION «LOCAL ROADS OF KHERSON REGION» Категорія замовника: Legal person providing the needs of the state or territorial community Kind: Legal person providing the needs of the state or territorial community Ідентифікаційний код замовника в 43538115 ЄДР: National ID: 43538115 Місцезнаходження замовника: проспект Ушакова, будинок 47, місто Херсон, Херсонська область, 73000, Україна Контактна особа замовника, Веніслав Наталія Іванівна, [email protected], уповноважена здійснювати зв’язок з +380958246154 учасниками: Contact point: [email protected], +380958246154, Venislav Nataliia Вид предмета закупівлі: services Main procurement category: services Назва предмета закупівлі: Розроблення технічних документацій із землеустрою щодо встановлення (відновлення) меж земельних ділянок, здійснення державної реєстрації земельних ділянок в Державному земельному кадастрі під автомобільні дороги загального користування місцевого значення О220701 Новогригорівка-Новий Азов-Азовське, О220702 Новодмитрівка-Новоолексіївка, О220703 Петрівка- Сокологірне, О220704 /Р-47/ - Червоне, О220705 Чаплинка-Новотроїцьке-Рикове, О220706 Генічеськ- Стрілкове, О220707 Олексіївка-/М-18/ , О220709 Об’їзд центральної частини міста Генічеська, О220712 Приозерне-Генічеська Гірка, О220713 Бойове-Олексіївка , О220714 Новий Мир- Гордієнківці-Рикове, О220715 /М-18/-Ясна Поляна, О220717 Перекоп-Пчілка, О220718 Новодмитрівка- -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel