Why Did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report: Tough Choices Facing Florida's Governments

TOUGH CHOICES FACING FLORIDA’S GOVERNMENTS PATTERNS OF RESEGREGATION IN FLORIDA’S SCHOOLS SEPTEMBER 2017 Tough Choices Facing Florida’s Governments PATTERNS OF RESEGREGATION IN FLORIDA’S SCHOOLS By Gary Orfield and Jongyeon Ee September 27, 2017 A Report for the LeRoy Collins Institute, Florida State University Patterns of Resegregation in Florida’s Schools 1 Tough Choices Facing Florida’s Governments TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ..............................................................................................................................................................3 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................3 Patterns of Resegregation in Florida’s Schools .........................................................................................................4 The Context of Florida’s School Segregation.............................................................................................................5 Three Supreme Court Decisions Negatively Affecting Desegregation .......................................................................6 Florida Since the 1990s .............................................................................................................................................7 Overview of Trends in Resegregation of Florida’s Schools ........................................................................................7 Public School Enrollment Trend -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

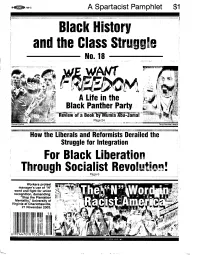

Black History and the Class Struggle

®~759.C A Spartacist Pamphlet $1 Black History i! and the Class Struggle No. 18 Page 24 ~iI~i~·:~:f!!iI'!lIiAI_!Ii!~1_&i 1·li:~'I!l~~.I_ :lIl1!tl!llti:'1!):~"1i:'S:':I'!mf\i,ri£~; : MINt mm:!~~!!)rI!t!!i\i!Ui\}_~ How the Liberals and Reformists Derailed the Struggle for Integration For Black Liberation Through Socialist Revolution! Page 6 VVorkers protest manager's use of "N" word and fight for union recognition, demanding: "Stop the Plantation Mentality," University of Virginia at Charlottesville, , 21 November 2003. I '0 ;, • ,:;. i"'l' \'~ ,1,';; !r.!1 I I -- - 2 Introduction Mumia Abu-Jamal is a fighter for the dom chronicles Mumia's political devel Cole's article on racism and anti-woman oppressed whose words teach powerful opment and years with the Black Panther bigotry, "For Free Abortion on Demand!" lessons and rouse opposition to the injus Party, as well as the Spartacist League's It was Democrat Clinton who put an "end tices of American capitalism. That's why active role in vying to win the best ele to welfare as we know it." the government seeks to silence him for ments of that generation from black Nearly 150 years since the Civil War ever with the barbaric death penaIty-a nationalism to revolutionary Marxism. crushed the slave system and won the legacy of slavery-,-Qr entombment for life One indication of the rollback of black franchise for black people, a whopping 13 for a crime he did not commit. The frame rights and the absence of militant black percent of black men were barred from up of Mumia Abu-Jamal represents the leadership is the ubiquitous use of the voting in the 2004 presidential election government's fear of the possibility of "N" word today. -

Mountain Republicans and Contemporary Southern Party Politics

Journal of Political Science Volume 23 Number 1 Article 2 November 1995 Forgotten But Not Gone: Mountain Republicans and Contemporary Southern Party Politics Robert P. Steed Tod A. Baker Laurence W. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Steed, Robert P.; Baker, Tod A.; and Moreland, Laurence W. (1995) "Forgotten But Not Gone: Mountain Republicans and Contemporary Southern Party Politics," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 23 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol23/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORGOTTEN BUT NOT GONE: MOUNTAIN REPUBLICANS AND CONTEMPORARY SOUTHERN PARTY POLITICS Robert P. Steed, The Citadel Tod A. Baker, The Citadel Laurence W. Moreland, The Citadel Introduction During the period of Democratic Party dominance of southern politics, Republicans were found mainly in the mountainous areas of western Virginia, western North Carolina, and eastern Tennessee and in a few other counties (e.g., the German counties of eas't central Te_xas) scattered sparsely in the region. Never strong enough to control statewide elections, Republicans in these areas were competitive locally, frequently succeeding in winning local offices. 1 As southern politics changed dramatically during the post-World War II period, research on the region's parties understandably focused on the growth of Republican support and organizational development in those geographic areas and electoral arenas historically characterized by Democratic control. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

From: What Brown V

The following is excerpted from: What Brown v. Board of Education Should Have Said: America's Top Legal Experts Rewrite America's Landmark Civil Rights Decision, Jack M. Balkin, ed. (New York University Press 2001), pp. 3-8. It appeared as an article in the Winter 2002 issue of the Yale Law Report. Brown as Icon In the half century since the Supreme Court's 1954 decision, Brown v. Board of Education has become a beloved legal and political icon. Brown is one of the most famous Supreme Court opinions, better known among the lay public than Marbury v. Madison, which confirmed the Supreme Court's power of judicial review, or McCulloch v. Maryland, which first offered an expansive interpretation of national powers under the Constitution. Indeed, in terms of sheer name recognition, Brown ranks with Miranda v. Arizona, whose warnings delivered to criminal suspects appear on every police show, or the abortion case, Roe v. Wade, which has been a consistent source of political and legal controversy since it was handed down in 1973. Even if Brown is less well known than Miranda or Roe, there is no doubt that it is the single most honored opinion in the Supreme Court's corpus. The civil rights policy of the United States in the last half century has been premised on the correctness of Brown, even if people often disagree (and disagree heatedly) about what the opinion stands for. No federal judicial nominee, and no mainstream national politician today would dare suggest that Brown was wrongly decided. At most they might suggest that the opinion was inartfully written, that it depended too much on social science literature, that it did not go far enough, or that it has been misinterpreted by legal and political actors to promote an unjust political agenda. -

Forgotten Heroes: Lessons from School Integration in a Small Southern Community Whitney Elizabeth Cate East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2012 Forgotten Heroes: Lessons from School Integration in a Small Southern Community Whitney Elizabeth Cate East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Cate, Whitney Elizabeth, "Forgotten Heroes: Lessons from School Integration in a Small Southern Community" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1512. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1512 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forgotten Heroes: Lessons from School Integration in a Small Southern Community _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History _____________________ by Whitney Elizabeth Cate December 2012 _____________________ Committee Chair, Dr. Elwood Watson Dr. Emmitt Essin Dr. David Briley Keywords: Integration, Segregation, Brown vs. Board of Education, John Kasper ABSTRACT Forgotten Heroes: Lessons from School Integration in a Small Southern Community by Whitney Elizabeth Cate In the fall of 1956 Clinton High School in Clinton, Tennessee became the first public school in the south to desegregate. This paper examines how the quiet southern town handled the difficult task of forced integration while maintaining a commitment to the preservation of law and order. -

Cooper V. Aaron and Judicial Supremacy

University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review Volume 41 Issue 2 The Ben J. Altheimer Symposium-- Article 11 Cooper v. Aaron: Still Timely at Sixty Years 2019 Cooper v. Aaron and Judicial Supremacy Christopher W. Schmidt Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Christopher W. Schmidt, Cooper v. Aaron and Judicial Supremacy, 41 U. ARK. LITTLE ROCK L. REV. 255 (2019). Available at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol41/iss2/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review by an authorized editor of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COOPER V. AARON AND JUDICIAL SUPREMACY Christopher W. Schmidt* “[T]he Federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution.” — Cooper v. Aaron (1958)1 “The logic of Cooper v. Aaron was, and is, at war with the basic principles of democratic government, and at war with the very meaning of the rule of law.” — Attorney General Edwin Meese III (1986)2 I. INTRODUCTION The greatest Supreme Court opinions are complex heroes. They have those attributes that make people recognize them as great: the strategic brilliance and bold assertion of the authority of judicial review in Marbury v. Madison;3 the common-sense refutation of the fallacies that justified racial segregation in Brown v. Board of Education;4 the recognition that something as fundamental as a right to privacy must be a part of our constitutional protections in Griswold v. -

Building a Progressive Center Political Strategy and Demographic Change in America

Building a Progressive Center Political Strategy and Demographic Change in America Matt Browne, John Halpin, and Ruy Teixeira April 2011 The “Demographic Change and Progressive Political Strategy” series of papers is a joint project organized under the auspices of the Global Progress and Progressive Studies programs and the Center for American Progress. The research project was launched following the inaugural Global Progress conference held in October 2009 in Madrid, Spain. The preparatory paper for that conference, “The European Paradox,” sought to analyze why the fortunes of European progressive parties had declined following the previous autumn’s sudden financial collapse and the global economic recession that ensued. The starting premise was that progressives should, in principle, have had two strengths going for them: • Modernizing trends were shifting the demographic terrain in their political favor. • The intellectual and policy bankruptcy of conservatism, which had now proven itself devoid of creative ideas of how to shape the global economic system for the common good. Despite these latent advantages, we surmised that progressives in Europe were struggling for three pri- mary reasons. First, it was increasingly hard to differentiate themselves from conservative opponents who seemed to be wholeheartedly adopting social democratic policies and language in response to the eco- nomic crisis. Second, the nominally progressive majority within their electorate was being split between competing progressive movements. Third, their traditional working-class base was increasingly being seduced by a politics of identity rather than economic arguments. In response, we argued that if progressives could define their long-term economic agenda more clearly— and thus differentiate themselves from conservatives—as well as establish broader and more inclusive electoral coalitions, and organize more effectively among their core constituencies to convey their mes- sage, then they should be able to resolve this paradox. -

A History of the Virginia Democratic Party, 1965-2015

A History of the Virginia Democratic Party, 1965-2015 A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation “with Honors Distinction in History” in the undergraduate colleges at The Ohio State University by Margaret Echols The Ohio State University May 2015 Project Advisor: Professor David L. Stebenne, Department of History 2 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Mills Godwin, Linwood Holton, and the Rise of Two-Party Competition, 1965-1981 III. Democratic Resurgence in the Reagan Era, 1981-1993 IV. A Return to the Right, 1993-2001 V. Warner, Kaine, Bipartisanship, and Progressive Politics, 2001-2015 VI. Conclusions 4 I. Introduction Of all the American states, Virginia can lay claim to the most thorough control by an oligarchy. Political power has been closely held by a small group of leaders who, themselves and their predecessors, have subverted democratic institutions and deprived most Virginians of a voice in their government. The Commonwealth possesses the characteristics more akin to those of England at about the time of the Reform Bill of 1832 than to those of any other state of the present-day South. It is a political museum piece. Yet the little oligarchy that rules Virginia demonstrates a sense of honor, an aversion to open venality, a degree of sensitivity to public opinion, a concern for efficiency in administration, and, so long as it does not cost much, a feeling of social responsibility. - Southern Politics in State and Nation, V. O. Key, Jr., 19491 Thus did V. O. Key, Jr. so famously describe Virginia’s political landscape in 1949 in his revolutionary book Southern Politics in State and Nation. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

Tennessee, the Solid South, and the 1952 Presidential Election

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 5-9-2020 Y'all Like Ike: Tennessee, the Solid South, and the 1952 Presidential Election Cameron N. Regnery University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Regnery, Cameron N., "Y'all Like Ike: Tennessee, the Solid South, and the 1952 Presidential Election" (2020). Honors Theses. 1338. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1338 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Y’ALL LIKE IKE: TENNESSEE, THE SOLID SOUTH, AND THE 1952 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION by Cameron N. Regnery A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford April 2020 Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Darren Grem __________________________________ Reader: Dr. Rebecca Marchiel __________________________________ Reader: Dr. Conor Dowling © 2020 Cameron N. Regnery ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents for supporting me both in writing this thesis and throughout my time at Ole Miss. I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Darren Grem, for helping me with both the research and writing of this thesis. It would certainly not have been possible without him.