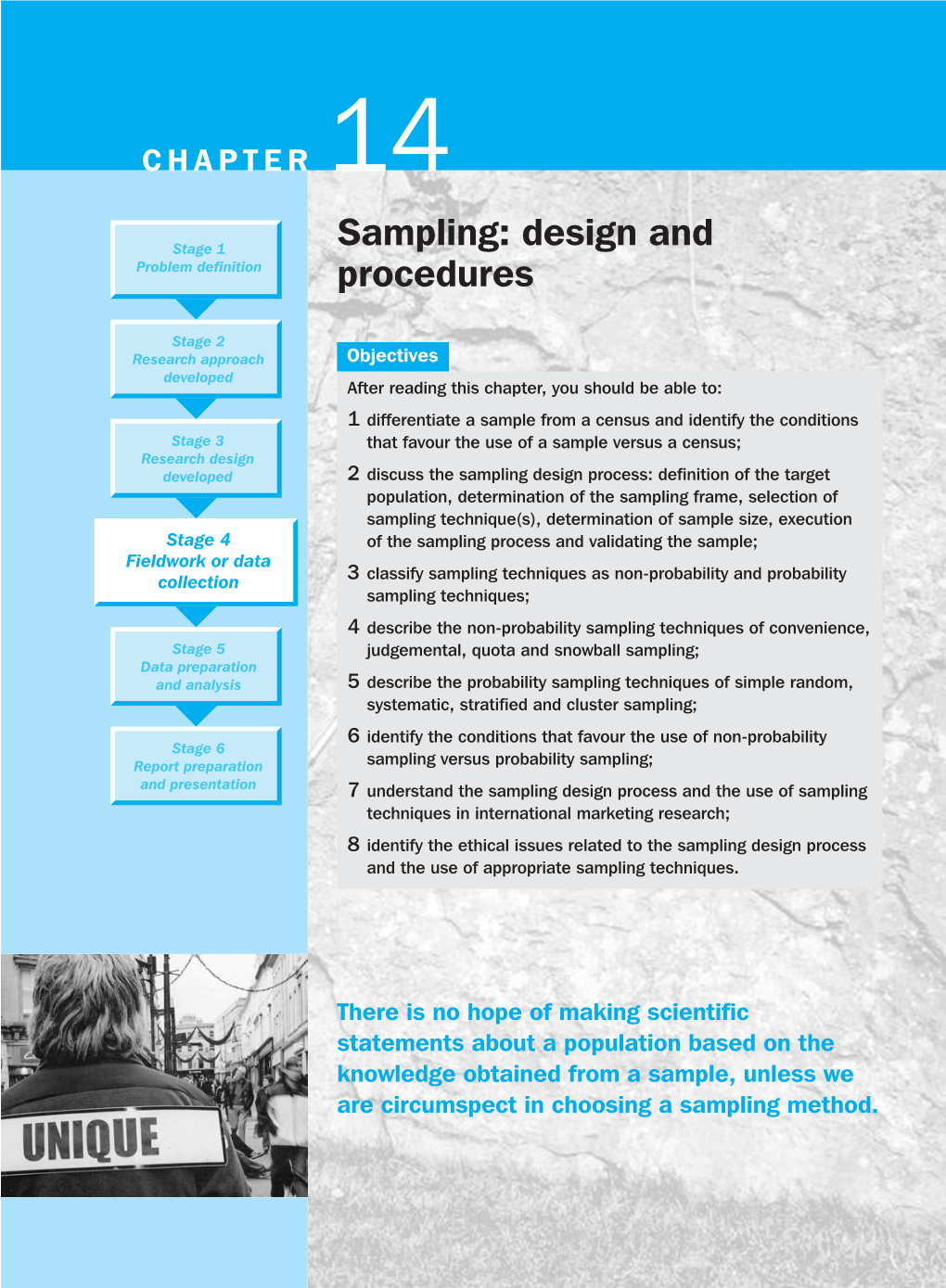

Sampling: Design and Procedures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sampling and Fieldwork Practices in Europe

www.ssoar.info Sampling and Fieldwork Practices in Europe: Analysis of Methodological Documentation From 1,537 Surveys in Five Cross-National Projects, 1981-2017 Jabkowski, Piotr; Kołczyńska, Marta Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Jabkowski, P., & Kołczyńska, M. (2020). Sampling and Fieldwork Practices in Europe: Analysis of Methodological Documentation From 1,537 Surveys in Five Cross-National Projects, 1981-2017. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 16(3), 186-207. https://doi.org/10.5964/meth.2795 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-74317-3 METHODOLOGY Original Article Sampling and Fieldwork Practices in Europe: Analysis of Methodological Documentation From 1,537 Surveys in Five Cross-National Projects, 1981-2017 Piotr Jabkowski a , Marta Kołczyńska b [a] Faculty of Sociology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland. [b] Department of Socio-Political Systems, Institute of Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Science, Warsaw, Poland. Methodology, 2020, Vol. 16(3), 186–207, https://doi.org/10.5964/meth.2795 Received: 2019-03-23 • Accepted: 2019-11-08 • Published (VoR): 2020-09-30 Corresponding Author: Piotr Jabkowski, Szamarzewskiego 89C, 60-568 Poznań, Poland. +48 504063762, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article addresses the comparability of sampling and fieldwork with an analysis of methodological data describing 1,537 national surveys from five major comparative cross-national survey projects in Europe carried out in the period from 1981 to 2017. -

ESOMAR 28 Questions

Responses to ESOMAR 28 Questions INTRODUCTION Intro to TapResearch TapResearch connects mobile, tablet and pc users interested in completing surveys with market researchers who need their opinions. Through our partnerships with dozens of leading mobile apps, ad networks and websites, we’re able to reach an audience exceeding 100 million people in the United States. We are focused on being a top-quality partner for ad hoc survey sampling, panel recruitment, and router integrations. Our technology platform enables reliable feasibility estimates, highly competitive costs, sophisticated quality enforcement, and quick-turnaround project management. Intro to ESOMAR ESOMAR (European Society for Opinion and Market Research) is the essential organization for encouraging, advancing and elevating market research worldwide. Since 1948, ESOMAR’s aim has been to promote the value of market and opinion research in effective decision-making. The ICC/ESOMAR Code on Market and Social Research, which was developed jointly with the International Chamber of Commerce, sets out global guidelines for self-regulation for researchers and has been undersigned by all ESOMAR members and adopted or endorsed by more than 60 national market research associations worldwide. Responses to ESOMAR 28 Questions COMPANY PROFILE 1) What experience does your company have in providing online samples for market research? TapResearch connects mobile, tablet and pc users interested in completing surveys with market researchers who need their opinions. Through our partnerships with dozens of leading mobile apps, ad networks and websites, we’re able to reach an audience exceeding 100 million people in the United States - we’re currently adding about 30,000 panelists/day and this rate is increasing. -

Esomar/Grbn Guideline for Online Sample Quality

ESOMAR/GRBN GUIDELINE FOR ONLINE SAMPLE QUALITY ESOMAR GRBN ONLINE SAMPLE QUALITY GUIDELINE ESOMAR, the World Association for Social, Opinion and Market Research, is the essential organisation for encouraging, advancing and elevating market research: www.esomar.org. GRBN, the Global Research Business Network, connects 38 research associations and over 3500 research businesses on five continents: www.grbn.org. © 2015 ESOMAR and GRBN. Issued February 2015. This Guideline is drafted in English and the English text is the definitive version. The text may be copied, distributed and transmitted under the condition that appropriate attribution is made and the following notice is included “© 2015 ESOMAR and GRBN”. 2 ESOMAR GRBN ONLINE SAMPLE QUALITY GUIDELINE CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE ................................................................................................... 4 2 DEFINITIONS .............................................................................................................................. 4 3 KEY REQUIREMENTS ................................................................................................................ 6 3.1 The claimed identity of each research participant should be validated. .................................................. 6 3.2 Providers must ensure that no research participant completes the same survey more than once ......... 8 3.3 Research participant engagement should be measured and reported on ............................................... 9 3.4 The identity and personal -

Lesson 3: Sampling Plan 1. Introduction to Quantitative Sampling Sampling: Definition

Quantitative approaches Quantitative approaches Plan Lesson 3: Sampling 1. Introduction to quantitative sampling 2. Sampling error and sampling bias 3. Response rate 4. Types of "probability samples" 5. The size of the sample 6. Types of "non-probability samples" 1 2 Quantitative approaches Quantitative approaches 1. Introduction to quantitative sampling Sampling: Definition Sampling = choosing the unities (e.g. individuals, famililies, countries, texts, activities) to be investigated 3 4 Quantitative approaches Quantitative approaches Sampling: quantitative and qualitative Population and Sample "First, the term "sampling" is problematic for qualitative research, because it implies the purpose of "representing" the population sampled. Population Quantitative methods texts typically recognize only two main types of sampling: probability sampling (such as random sampling) and Sample convenience sampling." (...) any nonprobability sampling strategy is seen as "convenience sampling" and is strongly discouraged." IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Sampling This view ignores the fact that, in qualitative research, the typical way of IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIII selecting settings and individuals is neither probability sampling nor IIIII convenience sampling." IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII It falls into a third category, which I will call purposeful selection; other (= «!Miniature population!») terms are purposeful sampling and criterion-based selection." IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII This is a strategy in which particular settings, persons, or activieties are selected deliberately in order to provide information that can't be gotten as well from other choices." Maxwell , Joseph A. , Qualitative research design..., 2005 , 88 5 6 Quantitative approaches Quantitative approaches Population, Sample, Sampling frame Representative sample, probability sample Population = ensemble of unities from which the sample is Representative sample = Sample that reflects the population taken in a reliable way: the sample is a «!miniature population!» Sample = part of the population that is chosen for investigation. -

Chapter 3: Simple Random Sampling and Systematic Sampling

Chapter 3: Simple Random Sampling and Systematic Sampling Simple random sampling and systematic sampling provide the foundation for almost all of the more complex sampling designs that are based on probability sampling. They are also usually the easiest designs to implement. These two designs highlight a trade-off inherent in all sampling designs: do we select sample units at random to minimize the risk of introducing biases into the sample or do we select sample units systematically to ensure that sample units are well- distributed throughout the population? Both designs involve selecting n sample units from the N units in the population and can be implemented with or without replacement. Simple Random Sampling When the population of interest is relatively homogeneous then simple random sampling works well, which means it provides estimates that are unbiased and have high precision. When little is known about a population in advance, such as in a pilot study, simple random sampling is a common design choice. Advantages: • Easy to implement • Requires little advance knowledge about the target population Disadvantages: • Imprecise relative to other designs if the population is heterogeneous • More expensive to implement than other designs if entities are clumped and the cost to travel among units is appreciable How it is implemented: • Select n sample units at random from N available in the population All units within the population must have the same probability of being selected, therefore each and every sample of size n drawn from the population has an equal chance of being selected. There are many strategies available for selecting a random sample. -

Intro Surveys for Honors Theses, 2009

PROGRAM ON SURVEY RESEARCH HARVARD UNIVERSITY ` Introduction to Survey Research ` The Survey Process ` Survey Resources at Harvard ` Sampling, Coverage, and Nonresponse ` Thinking About Modes April 14, 2009 ` Question Wording `Representation ◦The research design make inference to a larger population ◦Various population characteristics are represented in research data the same way there are present in population ◦Example: General population survey to estimate population characteristics Reporting `Realism Research Survey ◦A full picture of subjects emerges And ◦Relationships between multiple variables and multiple ways of looking at Methods the same variables can be studied Theories Analysis ◦Example: A qualitative case study to evaluate the nature of democracy in a small town with community meetings `Randomization ◦Variables which are not important in model are completely randomized ◦Effects of non-randomized variables can be tested ◦Example: Randomized clinical trial to test effectiveness of new cancer drug Integrated Example: Surveys and the Research Process Theories About Things `Good Measures: ◦Questions or measures impact your ability to study concepts ◦Think carefully about the underlying concepts a survey is trying to measure. Do the survey questions do a good job of capturing this? ◦The PSR Tip Sheet on Questionnaire Design contains good ideas on Concepts Population Validity External how to write survey questions. Specification Error ` Measures Sample Good Samples: ◦Samples give you the ability to generalize your findings Survey Errors ◦Think carefully about the population you are trying to generalize Internal Validity Internal your findings to. Does your sample design do a good job of Data Respondents representing these people? ◦The PSR Tip Sheet on Survey Sampling, Coverage, and Nonresponse contains thinks to think about in designing or evaluating a sample. -

R(Y NONRESPONSE in SURVEY RESEARCH Proceedings of the Eighth International Workshop on Household Survey Nonresponse 24-26 September 1997

ZUMA Zentrum für Umfragen, Melhoden und Analysen No. 4 r(y NONRESPONSE IN SURVEY RESEARCH Proceedings of the Eighth International Workshop on Household Survey Nonresponse 24-26 September 1997 Edited by Achim Koch and Rolf Porst Copyright O 1998 by ZUMA, Mannheini, Gerinany All rights reserved. No part of tliis book rnay be reproduced or utilized in any form or by aiiy means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any inforniation Storage and retrieval System, without permission in writing froni the publisher. Editors: Achim Koch and Rolf Porst Publisher: Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen (ZUMA) ZUMA is a member of the Gesellschaft Sozialwissenschaftlicher Infrastruktureinrichtungen e.V. (GESIS) ZUMA Board Chair: Prof. Dr. Max Kaase Dii-ector: Prof. Dr. Peter Ph. Mohlcr P.O. Box 12 21 55 D - 68072.-Mannheim Germany Phone: +49-62 1- 1246-0 Fax: +49-62 1- 1246- 100 Internet: http://www.social-science-gesis.de/ Printed by Druck & Kopie hanel, Mannheim ISBN 3-924220-15-8 Contents Preface and Acknowledgements Current Issues in Household Survey Nonresponse at Statistics Canada Larry Swin und David Dolson Assessment of Efforts to Reduce Nonresponse Bias: 1996 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) Preston. Jay Waite, Vicki J. Huggi~isund Stephen 1'. Mnck Tlie Impact of Nonresponse on the Unemployment Rate in the Current Population Survey (CPS) Ciyde Tucker arzd Brian A. Harris-Kojetin An Evaluation of Unit Nonresponse Bias in the Italian Households Budget Survey Claudio Ceccarelli, Giuliana Coccia and Fahio Crescetzzi Nonresponse in the 1996 Income Survey (Supplement to the Microcensus) Eva Huvasi anci Acfhnz Marron The Stability ol' Nonresponse Rates According to Socio-Dernographic Categories Metku Znletel anci Vasju Vehovar Understanding Household Survey Nonresponse Through Geo-demographic Coding Schemes Jolin King Response Distributions when TDE is lntroduced Hikan L. -

Lecture 8: Sampling Methods

Lecture 8: Sampling Methods Donglei Du ([email protected]) Faculty of Business Administration, University of New Brunswick, NB Canada Fredericton E3B 9Y2 Donglei Du (UNB) ADM 2623: Business Statistics 1 / 30 Table of contents 1 Sampling Methods Why Sampling Probability vs non-probability sampling methods Sampling with replacement vs without replacement Random Sampling Methods 2 Simple random sampling with and without replacement Simple random sampling without replacement Simple random sampling with replacement 3 Sampling error vs non-sampling error 4 Sampling distribution of sample statistic Histogram of the sample mean under SRR 5 Distribution of the sample mean under SRR: The central limit theorem Donglei Du (UNB) ADM 2623: Business Statistics 2 / 30 Layout 1 Sampling Methods Why Sampling Probability vs non-probability sampling methods Sampling with replacement vs without replacement Random Sampling Methods 2 Simple random sampling with and without replacement Simple random sampling without replacement Simple random sampling with replacement 3 Sampling error vs non-sampling error 4 Sampling distribution of sample statistic Histogram of the sample mean under SRR 5 Distribution of the sample mean under SRR: The central limit theorem Donglei Du (UNB) ADM 2623: Business Statistics 3 / 30 Why sampling? The physical impossibility of checking all items in the population, and, also, it would be too time-consuming The studying of all the items in a population would not be cost effective The sample results are usually adequate The destructive nature of certain tests Donglei Du (UNB) ADM 2623: Business Statistics 4 / 30 Sampling Methods Probability Sampling: Each data unit in the population has a known likelihood of being included in the sample. -

Survey Design

1 Survey Design Target population: The scope of ACES is to capture investment by all domestic, private, non-farm businesses, including agricultural non-farm business and businesses without employees. Investment made after applying for an Employer Identification Number (EIN) from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) but before having any payroll or receipts is also included. Major exclusions are foreign operations of U.S. businesses, businesses in the U.S. territories, government operations (including the U.S. Postal Service), agricultural production companies and private households. Sampling frame: ACES collects information at the company level. The records of how the company invests are maintained at the headquarters level, and not at the location of each physical operating location. Companies may elect to have divisions within the company report, but the sampling unit and tabulation unit will be the company. A company’s importance to the survey depends on their employment, payroll, and their business activity. The greater the number of employees or the larger the payroll, the more likely, in general, a company is to be selected in the sample. The influence that the amount of payroll has on the likelihood of selection is adjusted by the business activity such that two companies with similar payroll but in different business activities will not have the same likelihood of selection. This is done to improve the quality of the estimates from any particular ACES specific industry code for business activities. Estimates are from two distinct samples from distinct frames. The first frame collects in-scope companies with employees. Companies sampled from this frame will receive an ACE-1 form, and the frame and sample are the ACE-1 frame and sample, respectively. -

![Sampling and Household Listing Manual [DHSM4]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5729/sampling-and-household-listing-manual-dhsm4-1365729.webp)

Sampling and Household Listing Manual [DHSM4]

SAMPLING AND HOUSEHOLD LISTING MANuaL Demographic and Health Surveys Methodology This document is part of the Demographic and Health Survey’s DHS Toolkit of methodology for the MEASURE DHS Phase III project, implemented from 2008-2013. This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by MEASURE DHS/ICF International. [THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK] Demographic and Health Survey Sampling and Household Listing Manual ICF International Calverton, Maryland USA September 2012 MEASURE DHS is a five-year project to assist institutions in collecting and analyzing data needed to plan, monitor, and evaluate population, health, and nutrition programs. MEASURE DHS is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The project is implemented by ICF International in Calverton, Maryland, in partnership with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs, the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), Futures Institute, Camris International, and Blue Raster. The main objectives of the MEASURE DHS program are to: 1) provide improved information through appropriate data collection, analysis, and evaluation; 2) improve coordination and partnerships in data collection at the international and country levels; 3) increase host-country institutionalization of data collection capacity; 4) improve data collection and analysis tools and methodologies; and 5) improve the dissemination and utilization of data. For information about the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) program, write to DHS, ICF International, 11785 Beltsville Drive, Suite 300, Calverton, MD 20705, U.S.A. (Telephone: 301-572- 0200; fax: 301-572-0999; e-mail: [email protected]; Internet: http://www.measuredhs.com). -

STANDARDS and GUIDELINES for STATISTICAL SURVEYS September 2006

OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES FOR STATISTICAL SURVEYS September 2006 Table of Contents LIST OF STANDARDS FOR STATISTICAL SURVEYS ....................................................... i INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 SECTION 1 DEVELOPMENT OF CONCEPTS, METHODS, AND DESIGN .................. 5 Section 1.1 Survey Planning..................................................................................................... 5 Section 1.2 Survey Design........................................................................................................ 7 Section 1.3 Survey Response Rates.......................................................................................... 8 Section 1.4 Pretesting Survey Systems..................................................................................... 9 SECTION 2 COLLECTION OF DATA................................................................................... 9 Section 2.1 Developing Sampling Frames................................................................................ 9 Section 2.2 Required Notifications to Potential Survey Respondents.................................... 10 Section 2.3 Data Collection Methodology.............................................................................. 11 SECTION 3 PROCESSING AND EDITING OF DATA...................................................... 13 Section 3.1 Data Editing ........................................................................................................ -

The Rise of Survey Sampling

The rise of survey008uurveyey samplingsampli Jelke Bethlehem The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily refl ect the policies of Statistics Netherlands Discussion paper (09015) Statistics Netherlands The Hague/Heerlen, 2009 Explanation of symbols . = data not available * = provisional fi gure x = publication prohibited (confi dential fi gure) – = nil or less than half of unit concerned – = (between two fi gures) inclusive 0 (0,0) = less than half of unit concerned blank = not applicable 2005-2006 = 2005 to 2006 inclusive 2005/2006 = average of 2005 up to and including 2006 2005/’06 = crop year, fi nancial year, school year etc. beginning in 2005 and ending in 2006 2003/’04–2005/’06 = crop year, fi nancial year, etc. 2003/’04 to 2005/’06 inclusive Due to rounding, some totals may not correspond with the sum of the separate fi gures. Publisher Statistics Netherlands Henri Faasdreef 312 2492 JP The Hague Prepress Statistics Netherlands - Facility Services Cover TelDesign, Rotterdam Information Telephone .. +31 88 570 70 70 Telefax .. +31 70 337 59 94 Via contact form: www.cbs.nl/information Where to order E-mail: [email protected] Telefax .. +31 45 570 62 68 Internet www.cbs.nl ISSN: 1572-0314 © Statistics Netherlands, The Hague/Heerlen, 2009. Reproduction is permitted. ‘Statistics Netherlands’ must be quoted as source. 6008309015 X-10 The rise of survey sampling Jelke Bethlehem Summary: This paper is about the history of survey sampling. It describes how sampling became an accepted scientific method. From the first ideas in 1895 it took some 50 years before the principles of probabilit y sampling were widely accepted.