A Biodiversity Audit a Biodiversity Audit of the Tame and Trent River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

River Mease SAC Developer Contribution Scheme 2 Appendix

Appendix 1: Measures to be funded through the Developer Contributions Scheme 2 (DCS2) FINAL VERSION (June 2016) The need for DCS2 has been identified in response to the development allocations within the North West Leicestershire District Council Local Plan, which is currently being finalised. The Local Plan was subject to assessment under the Habitats Regulations1 and the Developer Contribution Scheme was identified as a key mechanism to provide NWLDC with the necessary confidence that development allocated within the catchment of the river will not be likely to have a significant effect on the River Mease SAC. The HRA of the Local Plan identified the need for DCS2 to deliver mitigation to facilitate the delivery of 1826 dwellings. On the basis of the estimated P loadings to the river from receiving works provided in E&F of DCS2, an estimate of phosphate contributions from these dwellings represents an increased loading of 329g P/day. Of critical importance to the development of DCS2, is an agreement which has been reached since the development and implementation of DCS1. Following recent discussions between Natural England, the Environment Agency and Severn Trent Water, the following statement has been issued. Severn Trent, Environment Agency and Natural England have assessed the options to meet the SAC conservation objectives in relation to flow and phosphate, and agree that pumping sewage effluent from Packington and Measham sewage works out of the Mease catchment is the most effective long term solution. The primary reason to move flow out of the River Mease catchment would be to ensure the SAC flow targets are met. -

Lichfield District Council

Register of Buildings of Special Local Interest Alrewas Conservation Area (23) Church Road Outbuilding to front of Cranfield House Buildings adjacent to Gaskells Bridge Cotton Close Numbers 24-30 (former mill) Furlong Lane 20b Heron Court Numbers 3, 4 and 5 Swallow Court Numbers 3, 4 and 5 Kings Bromley Road Jaipur Restaurant13 Barns adjacent to Navigation Cottage Main Street War Memorial 57 60 100 (Coates Butchers) Building adjacent to number 168 170 Mays Walk Numbers 1, 2 and 3 Park Road Outbuildings to Number 4 6 Essington House Farm and outbuildings Post Office Road 1 (Post Office) The Crown PH Wellfield Road Alrewas Village Hall Clifton Campville Conservation Area (1) Church Street Clifton Campville Village Hall Colton Conservation Area (44) Bellamour Way, (North side) St Mary’s Primary School Elm Cottage Forge House The Forge Smithy Williscroft Place, numbers 1-8 inclusive The Greyhound PH Colton Lodge Cuckoo Barn Cypress Cottage High House Bellamour Way, (South side) Lloyds Cottages, numbers 1 & 2 Rose Villa Cottages, numbers 1 & 2 Lucy Berry Cottage War Memorial School House School Cottage Clerks House Oldham Cottages, numbers 1 to 8 inclusive The Coach House The Old Rectory High Street, Number 2 (Aspley House) Hollow Lane, The Cottages, numbers 1 & 2 Martlin Lane Martlin Cottages, numbers 1, 2, 3 & 4 . Elford (46) Road Name Property Name/Number Brickhouse Lane 1 New Cottage Burton Road The Mount Hill Cottage Elford House (including numbers 1, 2, 3 & 4 Elford House, East Wing, Elford House and West Wing Elford House) Elford Lodge -

Action for Nature

Action for Nature A Strategic Approach to Biodiversity, Habitat and the Local Environment for Leicestershire County Council Published June 2021 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Guiding Principles of our Approach 4 3. Legislative and Policy Context 5 4. Biodiversity and Natural Capital 18 5. Opportunities for Delivering the Biodiversity Objectives 28 6. Development and Implementation of the Delivery Plan 31 Appendix 1: Glossary of Terms 34 Appendix 2: Priority Habitats and Species in Leicestershire 37 Appendix 3: National Character Areas of Leicestershire 38 Appendix 4: Accessible Countryside & Woodland in 42 Leicestershire Appendix 5: Larger versions of maps used in document 44 Appendix 6: Sources of data 50 Action for Nature A Strategic Approach to Biodiversity, Habitat and the Local Environment for Leicestershire County Council 1. Introduction Working together for the benefit of everyone: Leicestershire County Council’s Strategic Plan 2018 to 20221 commits the Council to being ‘a carbon neutral organisation by 2030, to use natural resources wisely and to contribute to the recovery of nature’. The Council’s Environment Strategy 2018-20302, provides the vision behind this commitment: ‘We will minimise the environmental impact of our own activities and will improve the wider environment through local action. We will play our full part to protect the environment of Leicestershire., We will tackle climate change and embed environmental sustainability into what we do.’ This vision is supported by several aims and objectives that -

Rural Settlement Sustainability Study 2008

Rural Settlement Sustainability Study 2008 June 2008 Rural Settlement Sustainability Study 2008 Contents 1 Aims of the Study 3 2 Background to Rural Sustainability 5 3 Definition of Rural Settlements 9 4 Definition of Rural Services 11 5 Delivery of Rural Services 13 6 Inter-Relationship Between Rural Settlements & Urban Areas 15 7 Primary Services, Facilities & Jobs 17 8 Key Local Services & Facilities 19 9 Rural Accessibility 25 10 Sustainable Rural Settlement Summary 29 Appendices 1 Rural Settlements: Population & Dwellings i 2 Rural Transport: Car Ownership by Settlement iii 3 Sustainability Matrix: Access, Services & Facilities v June 2008 1 Aims of the Study 1.1 This report has been prepared to assist in the development of policies for sustainable development within Lichfield District. Information provided within the document will inform the preparation of a Core Strategy for the District as part of the Local Development Framework, in particular in the consideration of potential development locations within the District and an overall spatial strategy for longer term development having regard to principles of sustainability. 1.2 In his report on the Public Examination into the District Council’s first submitted Core Strategy (withdrawn 2006), the Inspector concluded that although there were proposed housing allocations within some of the District’s rural settlements, there was a lack of evidence in relation to the suitability of villages in the District to accommodate growth. He considered that the relative sustainability of different settlements should have been assessed as part of the preparation of the Core Strategy. He indicated that an assessment of the sustainability of rural settlements would ensure that the scale and location of development outside the District’s two main towns was driven by overall sustainability considerations, rather than simply the availability of previously developed land. -

Annual Monitoring Report 2011

Annual Monitoring Report 2011 December 2011 Annual Monitoring Report 2011 1 Lichfield District within the West Midlands Region 3 2 Executive Summary 4 3 Introduction 12 4 Business Development 25 5 Housing 34 6 Environmental Quality 46 7 Historic Environment 58 8 Transport & Local Services 61 9 Community Engagement 68 10 Significant Effect Indicators 72 A Local Plan Saved Policies 75 Glossary 79 December 2011 1 Lichfield District within the West Midlands Region Lichfield District Council Stoke-on-Trent Burton upon Trent Stafford Rugeley Shresbury LICHFIELD DISTRICT Telford Tamworth Wolverhampton Bridgenorth Dudley Birmingham Lichfield DistricCtov eCntry ouncil Kidderminster Bromsgrove Warwick Worcester Hereford Lichfield District Council "(C) Crown Copyright - Lichfield District Council. Licence No: 100017765. Dated 2009" Map 1.1 Lichfield District within the West Midlands December 2011 3 Annual Monitoring Report 2011 2 Executive Summary 2.1 The 2011 Lichfield District Annual Monitoring Report (AMR) covers the period 1st April 2010 - 31st March 2011 and monitors the success of the District Council's policies in relation to a series of indicators. The purpose of this report is to identify any trends within the District which will help the Authority understand what is happening within the District now, and what could happen in the future. 2.2 This report covers a range of topic areas to provide a picture of the social, environmental and economic geography of Lichfield District. The monitoring process is hugely important to the planning process as it provides a review of any successes or failures, so that the authority can assess how policies are responding to the issues within the District. -

Fradley Locator Map Curborough Hilliards Cross Streethay Alrewas Orgreave Elford FRADLEY

Unit 1, Common Lane Fradley Park, Fradley Nr Lichfield Tel: +44 (0) 1543 444 120 Staffordshire Fax: +44 (0) 1543 444 287 WS13 8NQ A523 Stoke-on A610 -Trent TRAVEL INFORMATION Motorway Map A52 A530 A6 Whitchurch Ashbourne A5 Newcastle- 2 8 From Derby & Burton-on-Trent: A50 under-Lyme A3 Derby Continue along the A38 through Burton-on-Trent towards 53 A515 A Uttoxeter A52 A Stone Lichfield. Continue past Alrewas and the petrol station on the Market 519 A50 8 A50 right. Exit along the slip road and over the A38 following signs for Drayton A453 9 A51 4 Stafford Burton A A51 A 514 Fradley Park. Continue over the first roundabout, and right at the 4 upon Trent A 4 next. When you reach the mini roundabout turn right. Amethyst is 2 Newport Swadlincote A518 M A Rugeley 6 34 8 Fradley 3 A512 straight ahead. A A42 A51 A4 1 From Lichfield: 9 Cannock A5 4 Lichfield Telford 1 A5 Coalville Continue along the A38 towards Burton-on-Trent. Continue past A4 A5190 A44 A A5 M6 T signs for the A5192 & A5127. When you reach Hillards Cross, 46 M54 OL 4 L 7 Wolverhampton Brownhills Tamworth turn left towards Fradley Park. Continue over the first roundabout, Much 7 A5 A4 Wenlock Walsall A444 and right at the next. When you reach the mini roundabout turn A458 Hinckley A454 Dudley right. Amethyst is straight ahead. A38 A4 A458 6 Ledbur Bridgnorth BIRMINGHAM 4 6 Nuneaton 42 A The nearest Train Station is Lichfield Trent Valley and is a short M6 A442 9 taxi ride from Amethyst. -

Mease/Sence Lowlands

Character Area Mease/Sence 72 Lowlands Key Characteristics hedgerows have been diminished and sometimes removed. In the many areas of arable cultivation the hedgerow trees, which ● Gently-rolling landform of low rounded hills and comprise mainly ash and oak, are patchily distributed. The valleys. greatest extent of treecover comes from the large parklands at Gopsall Park, Market Bosworth, Thorpe Constantine and ● Flat land along river valleys. Shenton which often contain imposing mansions. ● Extensive, very open areas of arable cultivation. ● Strongly rectilinear hedge pattern of late enclosure, often dominating an open landscape. ● Tree cover confined to copses, spinneys, intermittent hedgerow trees and parks. ● Scattered large parks with imposing mansions. ● Small red-brick villages, often on hilltop sites and with prominent church spires. ● Ridge and furrow and deserted settlements. ● Isolated 19th century farmsteads. Landscape Character This area comprises the land hugging the western and southern flanks of the Leicestershire and South Derbyshire OB COUSINS/COUNTRYSIDE AGENCY OB COUSINS/COUNTRYSIDE Coalfield. The Trent valley forms its western boundary R between Burton upon Trent and Tamworth. From there Gently rolling clay ridges and shallow river valleys are framed by a eastwards it has a boundary with the Arden. On its south strongly rectilinear hedge pattern containing extensive areas of arable cultivation. eastern boundary this area merges with the Leicestershire Vales. Small villages, generally on the crests of the low ridges, are the most prominent features in the landscape other than The claylands surrounding the Mease and Sence fall unfortunately-sited pylons. Red brick cottages and houses southwards towards the valleys of the rivers Anker and with slate or pantile roofs cluster around spired churches Trent and are characterised by extensive areas of arable and, occasionally, timber framed buildings are to be seen in cultivation with low, sparse hedges and few hedgerow trees. -

Go Wild in the Tame Valley Wetlands

Tame Valley Wetlands in the Tame Valley Wetlands! An Educational Activity & Resource Pack Written and illustrated by Maggie Morland M.Ed. for TVWLPS ©2016 2 Contents Notes for Teachers & Group Leaders Page About the Tame Valley Wetlands Landscape Partnership Scheme 6 Introduction to this Educational Resource Pack 10 The Tame Valley Wetlands and the National Curriculum 11 Health and Safety – Generic Risk Assessment 12 Information Pages 20 Things you may not know about The River Tame 16 The Tame Valley Wetlands Landscape Partnership Scheme Area 18 Tame Valley Wetlands - A Timeline 19 A Countryside Code 22 Love Your River – Ten Point Plan (Warwickshire Wildlife Trust) 25 Places to Visit in the Tame Valley Wetlands Area 26 Activity Pages 1 Where does the river come from and go to? - (source, tributaries, confluence, 33 settlement, maps ) 2 Why does the river sometimes flood? - (water supply, rainfall, urban runoff, make a river 35 model) 3 When and how has the Tame Valley Wetlands area changed over time? - (local history, using timeline, river management, environmental change, mineral extraction, power 37 generation, agriculture, defence, transport, water supply, food, natural resources, industry) 4 How is the Tame Valley Wetlands area used now? - (Land use, conservation) 38 5 How can I be a naturalist and study habitats like John Ray? – (Explore habitats using all your senses, observation, recording, sketching, classification, conservation) 39 6 Food chain and food web games – (food chains/webs) 43 7 What lives in, on and by the Tame Valley -

River Basin Management Plan Humber River Basin District Annex C

River Basin Management Plan Humber River Basin District Annex C: Actions to deliver objectives Contents C.1 Introduction 2 C. 2 Actions we can all take 8 C.3 All sectors 10 C.4 Agriculture and rural land management 16 C.5 Angling and conservation 39 C.6 Central government 50 C.7 Environment Agency 60 C.8 Industry, manufacturing and other business 83 C.9 Local and regional government 83 C.10 Mining and quarrying 98 C.11 Navigation 103 C.12 Urban and transport 110 C.13 Water industry 116 C.1 Introduction This annex sets out tables of the actions (the programmes of measures) that are proposed for each sector. Actions are the on the ground activities that will implemented to manage the pressures on the water environment and achieve the objectives of this plan. Further information relating to these actions and how they have been developed is given in: • Annex B Objectives for waters in the Humber River Basin District This gives information on the current status and environmental objectives that have been set and when it is planned to achieve these • Annex D Protected area objectives (including programmes for Natura 2000) This gives details of the location of protected areas, the monitoring networks for these, the environmental objectives and additional information on programmes of work for Natura 2000 sites. • Annex E Actions appraisal This gives information about how we have set the water body objectives for this plan and how we have selected the actions • Annex F Mechanisms for action This sets out the mechanisms - that is, the policy, legal, financial and voluntary arrangements - that allow actions to be put in place The actions are set out in tables for each sector. -

Chapter Eight: a Lost Way of Life – Farms in the Parish

Chapter Eight: A lost way of life – farms in the parish Like everywhere else in England, the farms in Edingale parish have consolidated, with few of the post-inclosure farms remaining now as unified businesses. Of the 13 farms listed here post-inclosure, only three now operate as full-time agricultural businesses based in the parish (ignoring the complication of Pessall Farm). While for more than 200 years, these farms were far and away the major employers in the parish, full-time non-family workers now account for fewer than ten people. Where this trend will finally end is hard to predict. Farms in Oakley As previously mentioned, the historic township of Oakley was split between the Catton and Elford estates. In 1939, a bible was presented to Mrs Anson, of Catton Hall, from the tenants and staff of the estate, which lists Mansditch, Raddle, Pessall Pitts, The Crosses, Donkhill Pits and Oakley House farms among others. So the Catton influence on Oakley extended well into the twentieth century. Oakley House, Oakley The Croxall registers record that the Haseldine family lived at Oakley, which we can presume to be Oakley House. The last entry for this family is 1620 and the registers then show two generations of the Dakin family living there: Thomas Dakin who died in 1657, followed by his son, Robert . Thomas was listed as being churchwarden of Croxall in 1626 and in 1633. Three generations of the Booth family then lived at Oakley House. John Booth, born in 1710, had seven children. His son George (1753-1836 ) married Catherine and they had thirteen children, including Charles (1788-1844) who married Anna Maria. -

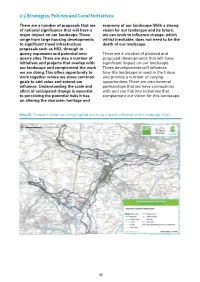

2.5 Strategies, Policies and Local Initiatives

2.5 Strategies, Policies and Local Initiatives There are a number of proposals that are economy of our landscape. With a strong of national significance that will have a vision for our landscape and its future, major impact on our landscape. These we can work to influence change, which range from large housing developments whilst inevitable, does not need to be the to significant travel infrastructure death of our landscape. proposals such as HS2, through to quarry expansion and potential new There are a number of planned and quarry sites. There are also a number of proposed developments that will have initiatives and projects that overlap with significant impact on our landscape. our landscape and complement the work These developments will influence we are doing. This offers opportunity to how the landscape is used in the future work together where we share common and provide a number of varying goals to add value and extend our opportunities. There are also external influence. Understanding the scale and partnerships that we have connections effect of anticipated change is essential with and can link into initiatives that to perceiving the potential risks it has complement our vision for this landscape. on altering the character, heritage and Map 26. Transport infrastructure highlighted as having a spatial influence on the landscape (LUC) 95 2.5.1 High Speed 2 (HS2) The planned route of HS2 cuts across at a level of detail sufficient to assess the landscape from Hilliard’s Cross, the actual impact of what is proposed, running north-west across the project depending as that impact does on the area for around 6.1km and exiting it quality, safety and convenience of both at Pipe Ridware. -

STAFFORDSHIRE. 145 • ((M.TTON Lis A

IDIRECTORY.J CRO.X.TON. STAFFORDSHIRE. 145 • ((M.TTON lis a. tolWili!!bip and small scattered village on Letters through Burton-upon-Trent arrive at 8 a.m. The rthe ::rreat, 6~ miles south from Burton-upon-Trent, and nearest money order office is at '\Valton-on-'frent &; 1 Ii ·s~west bom .Qroxall station, in the Burton-upon telegraph office at Walton. Letter bag called for at . Tre:nt nnion and panish (}f Croxall. Catton township bad 5-30 • a. chapel of its own, ser'Ved by the vicars of Croxall from •the time most prdbably ·of the Norman Conqnest, till OAKLEY is a township of the parish of Croxall. An , about 1750 a. d. when it was destroyed; portions of the iron bridge of three arches, on stone abutments, called ·fabric, a structure of La.ter Perpendicular date, are still Chetwynd Bridge, built in r824, crosses the river Tame. in existence in the Hall grounds, as well as a font, part on the high road from Alrewas, about a mile south-east • of a window &c. The ebapel, which stands near the Hall, of the Lichfield and Burton road. Howard Francis Paget was built as a &~~ of ease to the parish church, and esq. J.P. of Elford, and Henry Anson-Horton esq. of replaces an ancient Norman structure. There are 120 Catton Hall, are the principal landowners. The soil is sittings. Catton Hall is a noble mansion of brick, plea- a rich loam; subsoil. various. The chief crops are wheat. santly l'iitua.ted in a 'fine park of 92 acres.