Treatment of Cachexia in the Elderly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MMC International BV

M.M.C. International Steroid Substances Steroid Test A Colour Steroid Test B Colour Steroid Test B Colour with UV Light Stanozolol/ Oxandrolone Test Clenbuterol/ Oxymetholone Test Ephedrine Test Alfadolone Orange Yellow Nil - - - Androsterone Orange Yellow White - - - Beclometasone Brown–yellow Orange Nil - - - Betamethasone Orange–brown Pink–Orange Nil - - - Boldenone Base (Equipoise, Ganabol) (pure powder) Warm red after 2 min. Dark Orange after 2 min. Bright Light Orange - - - Boldenone Undecanoate (oil) Dark brownish-red Dark Red Bright Light Orange - - - Boldenone Undecylenate (oil) Orange - Light Brown Dark Orange → Brown Bright Light Orange-Yellow - - - Carbenoxolone (CBX) Orange Yellow Yellow - - - Cholesterol Violet Orange White - - - Clenbuterol (Spiropent, Ventipulmin) - - - - Purple - Dark brown with yellow-green on the Dark brown with yellow-green on the Clomiphene (Androxal, Clomid, Omifin) Nil Dark brown to black No reaction Dark brown to black sides of the ampoule sides of the ampoule Cortisone Orange Yellow Green - - - Desoxycortone Blue–black Yellow Yellow - - - Dexamethasone Yellow Orange–pink Nil - - - Dienestrol Yellow Orange–red Nil - - - Diethylstilbestrol (DES) Orange (→yellow–green) Nil - - - Dimethisterone Brown–green Orange–red Yellow - - - Drostanolone Propionate (Masteron) (oil) Bright green Yellow-Orange Orange - - - Dydrogesterone (Duphaston) - Orange Green-Yellow - - - Enoxolone Orange Yellow Green-Yellow - - - Ephedrine (also for Pseudo- and Nor-Ephedrine) - - - - - Orange Estradiol (Oestradiol) Orange -

Interactions of Nandrolone and Psychostimulant Drugs on Central Monoaminergic Systems. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Research 30

Sanna Kailanto Sanna Kailanto Interactions of Nandrolone Sanna Kailanto and Psychostimulant Drugs RESEARCH Interactions of Nandrolone and RESEARCH Psychostimulant Drugs on Central on Central Monoaminergic Monoaminergic Systems Systems Monoaminergic Systems Monoaminergic Central on Drugs Psychostimulant and Nandrolone of Interactions This study had four main aims. First, it aimed to explore the effects of nandrolone decanoate on dopaminergic and serotonergic activities in rat brains. Second, it set out to assess whether nandrolone pre-exposure modulates the acute neurochemical and behavioral effects of psychostimulant drugs in experimental animals. A third aim was to investigate if AAS-pretreatment-induced changes in brain reward circuitry are reversible. Finally, the study was also intended to evaluate the role of androgen receptors in nandrolone’s ability to modulate the dopaminergic and serotonergic effects of stimulants. The results of the study show that AAS pretreatment inhibits the reward- related neurochemical and behavioral effects of amphetamine, MDMA and cocaine in experimental animals. Given that LMA, stereotyped behavior and accumbal outflow of DA and 5-HT are all related to reward, this study suggests that nandrolone, at tested doses, significantly affects the rewarding properties of stimulant drugs. Furthermore, it seems that these effects could be long- lasting and that the ability of nandrolone to modulate reward-related effects of stimulants depends on AR or ER activation. .!7BC5<2"HIFILD! National Institute for Health and Welfare P.O. Box 30 (Mannerheimintie 166) FI-00271 Helsinki, Finland Telephone: +358 20 610 6000 30 ISBN 978-952-245-258-0 www.thl.fi 30 2010 30 Sanna Kailanto Interactions of Nandrolone and Psychostimulant Drugs on Central Monoaminergic Systems Academic dissertAtIoN To be presented with the permission of the Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, for public examination in the Arppeanum auditorium, Helsinki University Museum, Snellmaninkatu 3, Helsinki, on April 29nd, at 12 o’clock noon. -

Identification of Steroid Esters in Cattle Hair at Ultra-Trace Levels

Application Note Identification of Steroid Esters in Cattle Hair at Ultra-Trace Levels Emmanuelle Bichon, Lauriane Rambaud, Stephanie Christien, Aurélien Béasse, Stephanie Prevost, Fabrice Monteau, Bruno Le Bizec, Peter Hancock Waters Corporation Abstract The aim of this study is to address some of the analytical challenges previously described when analyzing a wide range of steroid esters (boldenone, nandrolone, estradiol, and testosterone) in cattle hair. Benefits ■ Unambiguous determination of steroid esters at ng/g level in cattle hair ■ Method is five times faster than the established GC-MS/MS method, with all esters included in a single run ■ Provides an efficient and additional confirmatory method to overcome any inconclusive urine analyses ■ Allows the potential to improve the detection of all banned substances in cattle hair by reducing matrix interference ■ Provides the ability to detect and identify compounds for a long time after administration Introduction The safety of our food supply can no longer be taken for granted. As the world changes and populations continue to grow, so will the responsibility of organizations to meet the demand of safe food supplies. One route of human exposure to veterinary substances is through the food chain as a result of malpractice or illegal activities. The steroid esters are one group of substances causing concern, which might still be used as growth promoting agents, but are now forbidden from use in breeding animals in the European Union.1 No residues of these anabolic substances should -

NICODOM IR Drugs, 1463 Spectra

NICODOM IR Drugs, 1463 spectra The infrared spectral library „NICODOM IR Drugs“ is an advanced collection of 1463 FTIR (ATR) digital spectra of drugs and related compounds. Typical information about the sample contains: Code Name Synonyms (up to 10 different synonyms) CAS Number Molecular weight Chemical Formula Manufacturer Example of included information: Code: DG0001 Name: Acebutolol Hydrochloride CAS: 34381-68-5 Formula: C18H29ClN2O4 Molecular weight: 372.891, Synonyms:N-[3-acetyl-4-(2-hydroxy-3-[isopropylamino]propoxy)phenyl]]-butanamide Manufacturer: Sigma The library includes spectra of analytical drug standards, street drugs and other helping substances. This FTIR spectral library can be purchased separatelly or as a part of cost effective library package “NICODOM IR Toxic/Hazardous Package, 7313 spectra“. The Nicodom FTIR spectra of toxic and hazardous compounds were collected using the FTIR Spectrometer Nexus 670 ™ (Thermo) and the Miracle™ single bounce ATR accessory (Pike Technologies) equipped by Diamond, ZnSe, or Si crystals. The Nicodom spectral library of polymers features resolution of 4cm-1 in the spectral range 600-4000 cm-1, measurement time 1 minute, the instrument was purged by dried air. The complete information is available in the full library version (not available in the demo list of compounds) The last library update has been done 2011, the Nicodom IR Libraries include many new substances which came to market during the last decade. This FTIR spectra library is available as digital searchable library compatible with your spectroscopic software. Also it can be delivered with SEARCH software or in *.pdf format. To download the list of spectra, to download a free demo library compatible with your software, to check the format compatibility as well as for pricelist, ordering info and information about all NICODOM IR/NIR Libraries and other NICODOM products please visit our webpage. -

RNA Sequencing in the Development of Cancer-Cachexia" (2017)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 RNA Sequencing in the Development of Cancer- Cachexia Thomas Allen Blackwell University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Cancer Biology Commons, Community Health and Preventive Medicine Commons, and the Kinesiology Commons Recommended Citation Blackwell, Thomas Allen, "RNA Sequencing in the Development of Cancer-Cachexia" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2434. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2434 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RNA Sequencing in the Development of Cancer-Cachexia A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Kinesiology by Thomas Blackwell Oklahoma State University Bachelor of Science in Health Education and Promotion, 2015 August 2017 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________ Dr. Nicholas Greene Thesis Director ____________________________ ____________________________ Dr. Tyrone Washington Dr. Walter Bottje Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Introduction: Cancer is a major public health problem in the U.S. and the world. In 2013 there were an estimated 1,660,290 new cases of cancer in the U.S. Cancer-Cachexia (CC) is a common effect of many cancers, and is directly responsible for 20-40% of cancer-related deaths. The mechanisms that control the development of CC are not well understood. Most investigations of CC focus on the post-cachectic state and do not examine the progression of the condition. -

Interactions of Nandrolone and Psychostimulant Drugs on Central Monoaminergic Systems

Sanna Kailanto Sanna Kailanto Interactions of Nandrolone Sanna Kailanto and Psychostimulant Drugs RESEARCH Interactions of Nandrolone and RESEARCH Psychostimulant Drugs on Central on Central Monoaminergic Monoaminergic Systems Systems Monoaminergic Systems Monoaminergic Central on Drugs Psychostimulant and Nandrolone of Interactions This study had four main aims. First, it aimed to explore the effects of nandrolone decanoate on dopaminergic and serotonergic activities in rat brains. Second, it set out to assess whether nandrolone pre-exposure modulates the acute neurochemical and behavioral effects of psychostimulant drugs in experimental animals. A third aim was to investigate if AAS-pretreatment-induced changes in brain reward circuitry are reversible. Finally, the study was also intended to evaluate the role of androgen receptors in nandrolone’s ability to modulate the dopaminergic and serotonergic effects of stimulants. The results of the study show that AAS pretreatment inhibits the reward- related neurochemical and behavioral effects of amphetamine, MDMA and cocaine in experimental animals. Given that LMA, stereotyped behavior and accumbal outflow of DA and 5-HT are all related to reward, this study suggests that nandrolone, at tested doses, significantly affects the rewarding properties of stimulant drugs. Furthermore, it seems that these effects could be long- lasting and that the ability of nandrolone to modulate reward-related effects of stimulants depends on AR or ER activation. .!7BC5<2"HIFILD! National Institute for Health and Welfare P.O. Box 30 (Mannerheimintie 166) FI-00271 Helsinki, Finland Telephone: +358 20 610 6000 30 ISBN 978-952-245-258-0 www.thl.fi 30 2010 30 Sanna Kailanto Interactions of Nandrolone and Psychostimulant Drugs on Central Monoaminergic Systems Academic disSertAtIoN To be presented with the permission of the Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, for public examination in the Arppeanum auditorium, Helsinki University Museum, Snellmaninkatu 3, Helsinki, on April 29nd, at 12 o’clock noon. -

Pros and Cons Controversy on Molecular Imaging and Dynamic

Open Access Archives of Biotechnology and Biomedicine Research Article Pros and Cons Controversy on Molecular Imaging and Dynamics of Double- ISSN Standard DNA/RNA of Human Preserving 2639-6777 Stem Cells-Binding Nano Molecules with Androgens/Anabolic Steroids (AAS) or Testosterone Derivatives through Tracking of Helium-4 Nucleus (Alpha Particle) Using Synchrotron Radiation Alireza Heidari* Faculty of Chemistry, California South University, 14731 Comet St. Irvine, CA 92604, USA *Address for Correspondence: Dr. Alireza Abstract Heidari, Faculty of Chemistry, California South University, 14731 Comet St. Irvine, CA 92604, In the current study, we have investigated pros and cons controversy on molecular imaging and dynamics USA, Email: of double-standard DNA/RNA of human preserving stem cells-binding Nano molecules with Androgens/ [email protected]; Anabolic Steroids (AAS) or Testosterone derivatives through tracking of Helium-4 nucleus (Alpha particle) using [email protected] synchrotron radiation. In this regard, the enzymatic oxidation of double-standard DNA/RNA of human preserving Submitted: 31 October 2017 stem cells-binding Nano molecules by haem peroxidases (or heme peroxidases) such as Horseradish Peroxidase Approved: 13 November 2017 (HPR), Chloroperoxidase (CPO), Lactoperoxidase (LPO) and Lignin Peroxidase (LiP) is an important process from Published: 15 November 2017 both the synthetic and mechanistic point of view. Copyright: 2017 Heidari A. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative -

甾体STEROIDS Testerone Series Nandrolone Series

武汉红禾杉生物科技有限公司 Wuhan Recedar Biotechnology Co., Ltd Tel: +86-027-59208096 E-mail: [email protected] 甾体 STEROIDS Testerone Series Product Name CAS No. 睾丸素 Testosterone Base 58-22-0 庚酸睾酮 Testosterone Enanthate 315-37-7 醋酸睾酮 Testosterone Acetate 1045-69-8 混合睾酮 Testosterone Sustanon 100 / 混合睾酮 Testosterone Sustanon 250 / 环戊丙酸睾酮 Testosterone Cypionate 58-20-8 苯丙酸睾酮 Testosterone Phenylpropionate 1255-49-8 异己酸睾酮 Testosterone Isocaproate 15262-86-9 癸酸睾酮 Testosterone Decanoate 5721-91-5 丙酸睾酮 Testosterone Propionate 57-85-2 十一酸睾酮 Testosterone Undecanoate 5949-44-0 甲基睾丸素 17-Methyltestosterone 58-18-4 4-氯去氢甲基睾酮 4-Chlorodehydromethyltestosterone 2446-23-3 醋酸氯睾酮 Clostebol Acetate 855-19-6 美雄诺龙 Mestanolone 521-11-9 雄诺龙 Stanolone 521-18-6 美睾酮(甲氢睾酮) Mesterolone 1424-00-6 氟甲睾酮 Fluoxymesterone 76-43-7 11-酮睾酮 11-Keto-Testosterone(Adrenosterone) 564-35-2 1-环戊丙酸睾酮 1-Test Cyp,Dihydroboldenone Cypiona 1-睾酮 1-Testosterone 196-56-5 17 羟基-17 甲基雄甾 2 烯 3 酮 17Beta-Hydroxy-17-Methylandrosta-4 1039-17-4 6-氯睾酮 Hexadrone Nandrolone Series Product Name CAS No. 诺龙 Nandrolone 434-22-0 癸酸诺龙 Nandrolone Decanoate(DECA) 360-70-3 苯丙酸诺龙 Nandrolone 62-90-3 Phenylpropionate(NPP,Durabolin) 环戊丙酸诺龙 Nandrolone Cypionate 601-63-8 丙酸诺龙 Nandrolone Propionate 7207-92-3 [email protected] Skype: live:kayy0613 Phone(Whatsapp): +8613164631693 武汉红禾杉生物科技有限公司 Wuhan Recedar Biotechnology Co., Ltd Tel: +86-027-59208096 E-mail: [email protected] Trenbolone Series Product Name CAS No. 群勃龙 Trenbolone Base 10161-33-8 群勃龙醋酸酯 Trenbolone Acetate 10161-34-9 群勃龙庚酸酯 Trenbolone Enanthate / 甲基群勃龙 Methyltrienolone 965-93-5 群勃龙环己甲基碳酸酯 Trenbolone Hexahydrobenzyl Carbonate(Parabolan) 23454-33-3 替勃龙 Tibolone 5630-53-5 Boldone Series Product Name CAS No. -

Nandrolone Decanoate, Behaviour and Brain: Animal Experimental Studies

NANDROLONE DECANOATE, BEHAVIOUR AND BRAIN: ANIMAL EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES by Ann-Sophie Lindqvist Doctoral Dissertation Department of Psychology, Göteborg University, Sweden, 2004 Dedicated to Roger DOCTORAL DISSERTATION AT GÖTEBORG UNIVERSITY 2004 Lindqvist, A-S. (2004). Nandrolone Decanoate, Behaviour and Brain: animal experimental studies. Department of Psychology, Göteborg University, Sweden. Abstract: Abuse of anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) has been linked to psychiatric and physiological complications in humans. Studies have further found a relationship between AAS abuse and abuse of alcohol and other drugs. The main objective of this animal experimental thesis was to examine to what extent the AAS compound nandrolone decanoate (ND; Deca-Durabol® [15 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks]) induces behavioural and physiological changes in sexually mature male rats, when compared to oil-treated control rats. One aim was to investigate if ND stimulates establishment of dominance in a provocative and competitive test situation and if ND enhances reactivity towards physical provocations. Fleeing and freezing behaviours in response to a threatening stimulus were further studied. Another aim was to investigate whether ND stimulates voluntary ethanol consumption and if ND alters behavioural tolerance to ethanol. The results showed that ND stimulated dominance in a competitive and provocative situation, enhanced reactivity to physical provocations and decreased fleeing and freezing responses. ND treatment further increased ethanol consumption and induced behavioural tolerance to ethanol. This thesis also studied if ND- induced reactivity towards physical provocations and ethanol intake were altered when combining ND treatment with physical activity. It was found that physical exercise accentuated the enhancing effects of ND on reactivity and to some degree on ethanol intake. -

Norethisterone Acetate Loestradiol at Four Application Sites

Nandrolone/Norethisterone 2119 fluid retention or adverse effect on renal function or serum-lipids. Pharmacopoeias. In Eur. (see p.vii). Mex.: Evra; Neth.: Evra; Norw.: Evra; Philipp.: Evra; Pol.: Evra; Port.: In these reports, intramuscular doses of nandrolone decanoate Ph. Eur. 6.2 (Nomegestrol Acetate). A white or almost white Evra; Rus.: Evra (Евра); S.Afr.: Evra; Singapore: Evra; Spain: Evra; Swed.: have ranged from 100 mg once every 2 weeks4 up to 600 mg crystalline powder. Practically insoluble in water; soluble in al- Evra; Switz.: Evra; Thai.: Evra; UK: Evra; USA: Ortho Evra; Venez.: Evra. weekly,2 and treatment has generally been given for 12 to 24 cohol; freely soluble in acetone. Protect from light. weeks. Profile Norethandrolone (BAN, rINN) ⊗ 1. Gold J, et al. Safety and efficacy of nandrolone decanoate for Nomegestrol acetate is a progestogen structurally related to pro- treatment of wasting in patients with HIV infection. AIDS 1996 17α-Ethyl-17β-hydroxyestr-4-en-3-one; 17β-Hydroxy-19-nor- 10: 745–52. gesterone (p.2125) that has been used in the treatment of men- 2. Sattler FR, et al. Effects of pharmacological doses of nandrolone strual disorders and as the progestogen component of menopau- 17α-pregn-4-en-3-one; Noretandrolona; Noréthandrolone; decanoate and progressive resistance training in immunodefi- sal HRT (p.2071). Typical oral doses are 5 mg daily for 10 to 14 Norethandrolonum. cient patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J days of a 28-day cycle. A subdermal implant is under investiga- Норэтандролон Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84: 1268–76. tion as a long-acting progestogen-only contraceptive. -

Application of COSMO-SAC to Solid Solubility in Pure and Mixed Solvent Mixtures for Organic Pharmacological Compounds

Application of COSMO-SAC to Solid Solubility in Pure and Mixed Solvent Mixtures for Organic Pharmacological Compounds Paul Eric Mullins Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Chemical Engineering Dr. Y. A. Liu, Chair Dr. Richey M. Davis Dr. Amadeu K. Sum 24 January 2007 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: COSMO, COSMO-SAC, Solubility, Pharmaceutical, Mixed Solvent Application of COSMO-SAC to Solid Solubility in Pure and Mixed Solvent Mixtures for Organic Pharmacological Compounds Paul Eric Mullins Dr. Y. A. Liu, Chair Abstract In this work, we present two open literature databases, the VT-2005 Sigma Profile Database and the VT-2006 Solute Sigma Profile Database, that contain sigma profiles for 1,645 unique compounds. A sigma profile is a molecular-specific distribution of the surface-charge density, which enables the application of solvation-thermodynamic models to predict vapor- liquid and solid-liquid equilibria, and other properties. The VT-2005 Sigma Profile Database generally focuses on solvents and small molecules, while the VT-2006 Solute Sigma Profile Database primarily consists of larger, pharmaceutical-related solutes. We design both of these databases for use with the conductor-like screening model – segment activity coefficient (COSMO-SAC), a liquid-phase activity-coefficient model. The databases contain the necessary information to perform binary and multicomponent VLE and SLE predictions. We offer detailed tutorials and procedures for use with our programs so the reader may also use their own research on our research group website (www.design.che.vt.edu). -

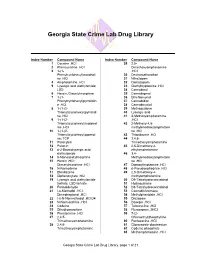

Compound Name

Georgia State Crime Lab Drug Library Index Number Compound Name Index Number Compound Name 1 Cocaine .HCl 29 2,5- 2 Phencyclidine .HCl Dimethoxyamphetamine 3 1-(1- .HCl Phenylcyclohexyl)morpholi 30 Dextromethorphan ne .HCl 31 Nitrazepam 4 Amphetamine .HCl 32 Clonazepam 5 Lysergic acid diethylamide; 33 Diethyltryptamine .HCl LSD 34 Cannabinol 6 Heroin; Diacetylmorphine 35 Cannabigerol 7 1-(1- 36 Ethchlorvynol Phenylcyclohexyl)pyrrolidin 37 Cannabidiol e .HCl 38 Cannabicyclol 8 1-(1-(2- 39 Methaqualone Thienyl)cyclohexyl)pyrrolidi 40 Lysergic acid ne .HCl 41 4-Methoxyamphetamine 9 1-(1-(2- .HCl Thienyl)cyclohexyl)morphol 42 2-Methoxy-4,5- ine .HCl methylenedioxyamphetami 10 1-(1-(2- ne .HCl Thienyl)cyclohexyl)piperidi 43 Thioridazine .HCl ne; TCP 44 3,4,5- 11 Psilocybin Trimethoxyamphetamine 12 Psilocin 45 2,5-Dimethoxy-4- 13 d-2-Bromolysergic acid ethylamphetamine diethylamide 46 3,4- 14 6-Monoacetylmorphine Methylenedioxyamphetami 15 Heroin .HCl; ne .HCl Diacetylmorphine .HCl 47 Dipropyltryptamine .HCl 16 N-Norcodeine 48 d-Pseudoephedrine .HCl 17 Etonitazene 49 2,5-Dimethoxy-4- 18 Diphenoxylate .HCl methylamphetamine 19 Lysergic acid diethylamide 50 D9-Tetrahydrocannabinol tartrate; LSD tartrate 51 Hydroquinone 20 Formaldehyde 52 D8-Tetrahydrocannabinol 21 l-a-Methadol .HCl; 53 Cannabichromene Dimepheptanol .HCl 54 Methylphenidate .HCl 22 l-a-N-Normethadol .HClO4 55 Diazepam 23 N-Normorphine .HCl 56 Doxepin .HCl 24 Codeine 57 Tetracycline .HCl 25 Dihydromorphine 58 Flurazepam .2HCl 26 Phentermine .HCl 59 7-(2- 27 2,4,5- Chloroethyl)theophylline