Healthy Ageing – a Challenge for Europe Union Member States and EFTA-EEA Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Determinants of Healthy Ageing in European Countries

Open Access Journal of Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine ISSN: 2575-8543 Research Article OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med Volume 4 Issue 5 - February 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Wim JA van den Heuvel DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2019.04.555649 Determinants of Healthy Ageing in European countries Wim JA van den Heuvel1* and Marinela Olaroiu2 1Share Research Institute, University Medical Centre, Netherlands 2Foundation Research and Advice in Care for Elderly (RACE), Heggerweg 2a, Netherlands Submission: January 24, 2019; Published: February 26, 2019 *Corresponding author: Wim JA van den Heuvel, Share Research Institute, University Medical Centre, Netherlands Abstract Background and Objectives: The concept of healthy ageing is still at debate, although healthy ageing is recognized as an important policy objective internationally. Evidence of which determinants or policies at country level may affect healthy ageing is lacking. This study explores level indicates the proportion of citizens at risk for poverty and access to services. Social cohesion at national level describes the extent to whichthe relationship citizens are between willing vulnerability,to accept each social other. cohesion, Resilience and at nationalresilience, level and includes healthy nationalageing in resources 31 European for citizens, countries. which Vulnerability may support at nationalthem to overcome adverse events. Research Design and Methods: This comparative study includes data from 2013 or 2014, based on validated, comparable international data sets, i.e. Eurostat and European Social Survey. Healthy ageing describes how many years a person is expected to live in good perceived health. Healthy ageing combines life expectancy with self-perceived health. Vulnerability, social cohesion and resilience are assessed using 10 indicators,Results: selected Mean healthy from the ageing mentioned in the 31data European sets. -

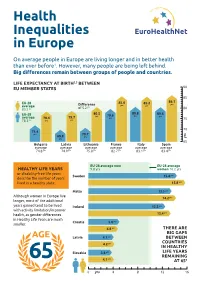

Health Inequalities in Europe (JAHEE)

90 85 86.1 yrs 85.2 85.6 EU-28 yrs yrs Difference yrs average of 5.2 83.5 yrs 80 80.6 80.8 80.5 EU-28 yrs yrs 79.6 yrs yrs 78.4 79.7 average 75 Health yrs yrs 78.3 yrs 70 71.4 yrs 70.7 69.8 yrs Inequalities yrs yrs 65 Spain Italy France Bulgaria Latvia Lithuania average average average average average average in Europe yrs yrs yrs yrs yrs yrs 83.4 83.1 82.7 74.8 74.9 75.8 On average people in Europe are living longer and in better health than ever before1. However, many people are being left behind. Big differences remain between groups of people and countries. LIFE EXPECTANCY AT BIRTH2,3 BETWEEN EU MEMBER STATES 90 85 86.1 EU-28 85.6 85.2 yrs Difference yrs yrs average yrs 83.5 yrs of 5.2 80 EU-28 80.5 80.8 80.6 yrs 79.6 yrs yrs average 78.4 79.7 yrs 75 78.3 yrs yrs yrs 70 71.4 yrs 70.7 69.8 yrs yrs yrs 65 Bulgaria Latvia Lithuania France Italy Spain average average average average average average 74.8 yrs 74.9 yrs 75.8 yrs 82.7 yrs 83.1 yrs 83.4 yrs EU-28 average men EU-28 average HEALTHY LIFE YEARS 9.8 yrs women 10.2 yrs or disability-free life years Sweden 15.4 yrs describe the number of years lived in a healthy state. -

Programme Book Is Printed on FSC Mix Paper

9th European Public Health Conference OVERVIEW PROGRAMME All for Health, WEDNESDAY 9 NOVEMBER THURSDAY 10 NOVEMBER FRIDAY 11 NOVEMBER SATURDAY 12 NOVEMBER 09:00 – 17:00 08:30 – 12:00 8:30 – 9:30 8:30 – 9:30 Pre-conferences Pre-conferences Parallel session 4 Parallel session 8 Health for All 9:40-10:40 9:40 – 10:40 Plenary 2 Parallel session 9 10:30 10:00 10:40 10:40 Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break 10th European Public Health Conference 2017 11th European Public Health Conference 2018 11:10-12:40 11:10 – 12:40 Stockholm, Sweden Ljubljana, Slovenia Parallel session 5 Parallel session 10 PROGRAMME 12:30 12:00 12:40 - 14:00 12:40 Lunch for pre-conference Lunch for pre-conference Lunch break Lunch break delegates only delegates only Lunch symposiums Join the Networks 13:00 – 13:40 14:00 – 15:00 13:40 – 14:40 Opening ceremony Plenary 3 Plenary 5 13:50 – 14:50 15:10 – 16:10 14:40 – 15:25 Parallel session 1 Parallel session 6 Closing ceremony Sustaining resilient Winds of Change: towards new ways 15:00 – 16:00 and healthy communities of improving public health in Europe Plenary 1 15:00 16:00 16:10 1 November - 4 November 2017 28 November - 1 December 2018 Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break Coffee/tea break Stockholmsmässan, Stockholm Cankarjev Dom, Ljubljana 16:30 – 17:30 16:40 – 17:40 Parallel session 2 Parallel session 7 #ephstockholm #eph2018 17:40 – 18:40 17:50 – 18:50 Parallel session 3 Plenary 4 19:30 – 22:00 19:30 – 23:59 Welcome reception Conference dinner 9 - 12 November 2016 www.ephconference.eu @ephconference -

Eurohealthnet Flyer

EuroHealthNet Ofice Rue de la loi, 67 B-1040 Brussels, Belgium tel. +32 2 235 03 20 fax. +32 2 235 03 39 Email: [email protected] Learn more about EuroHealthNet and its work: www.eurohealthnet.eu www.inequalities.eu www.health-gradient.eu www.equitychannel.net EuroHealthNet for a healthier Europe between and within countries What is EuroHealthNet? We pursue our goals through various projects in which EuroHealthNet has an active role as leader, coordinator or partner. EuroHealthNet is a not for profit network for public health, health promotion and disease prevention in Europe. We offer a valuable platform for information, The main topics of our projects are: advice, policy and advocacy on health-related issues at EU-Level. • Promoting health and equity • Determinants of health and health inequalities • Health in All Policies What is our mission? Some of our latest projects include: Our mission is to improve health and equity for people. The DETERMINE initiative establishes an EU Consortium for Action on the Socio-economic Determinants of In particular, EuroHealthNet works to: Health which aims to take forward the work of the WHO Commission on the SDH in an EU context. • Monitor relevant policy developments at EU level and in member countries www.health-inequalities.org • Manage and develop themed working groups, The GRADIENT research project addresses health which form a basis for advocacy work in the field inequalities among families and children with the aim of influencing policy-makers to take necessary steps to • Disseminate, share and transfer information and expertise reduce the health gradient. www.health-gradient.eu • Coordinate projects between members and with the European Commission The aim of equitychannel.net is to use innovative • Maintain an effective dialogue with EU institutions communications to stimulate and support changes in and other international organisations policies at international, national and local levels, and to help bring about greater health equity for all. -

Mental Health Services in the Community

Mental Health Services in the Community [Typ hier] Funded by the European Union in the frame of the 3rd EU Health Programme (2014-2020) Funded by the European Union in the frame of the 3rd EU Health Programmeme (2014-2020) This brochure was produced under the EU Health Programme (2014-2020) in the frame of a service contract with the Executive Agency (Chafea) acting under the mandate from the European Commission. The content of this brochure represents the views of the contractor and is its sole responsibility; it can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or Chafea or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and/or Chafea do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this brochure, nor do they accept responsibility for any use made by third parties thereof. This brochure represents the Deliverable 11b of the EU Compass Consortium under the service contract number 2014 71 03 on “Further development and implementation of the ‘EU Compass for Action on Mental Health and Well-being’”. The EU Compass is a tender commissioned by the European Commission and Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency and is implemented by a consortium led by the Trimbos Institute in the Netherlands, together with the NOVA University of Lisbon, the Finnish Association for Mental Health and EuroHealthNet under the supervision and in close cooperation with the “Group of Governmental Experts on Mental Health and Well-being”. Acknowledgements This brochure has been prepared by Bethany Hipple Walters, Jan Heijdra Suasnábar, and Ionela Petrea. -

The Gradient Evaluation Framework

THE GRADIENT EVALUATION FRAMEWORK A European framework for designing and evaluating policies and actions to level-up the gradient in health inequalities GEF among children, young people and their families Tackling the Professor John Kenneth Davies Dr Nigel Sherriff ii n n hh e e a a l l t t h h THE GRADIENT EVALUATION FRAMEWORK GEF Copyright © remains with the author(s) on behalf of the Gradient Consortium and the publisher. Published by the University of Brighton © University of Brighton, 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. www.health-gradient.eu The Gradient Project is co-funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (EC Grant Agreement No. 223252). Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on its behalf is liable for any use of the information contained in this publication. Davies, J.K. and Sherriff, N.S. (2012). The gradient evaluation framework (GEF): A European framework for designing and evaluating policies and actions to level-up the gradient in health inequalities among children, young people and their families. Brighton: University of Brighton. Project Coordinator Tackling the ii n n hh e e a a l l t t h h CONTENTS ABOUT THE GRADIENT PROJECT 2 USING THIS GEF PACK 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES 5 SECTION -

Childhood, Health Inequalities, and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

Childhood, health inequalities, and vaccine-preventable diseases Factsheet 1 THE MEASLES VACCINE HAS SAVED >20 million lives WORLDWIDE SINCE 2000. 1 in 10 Vaccination is a highly cost effective health intervention. It saves millions of people from certain infectious diseases, disability, and death each year. Vaccines protect health and children in the European region wellbeing and support the achievement of the remain vulnerable to potentially life- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)². threatening diseases as they have not received a basic set of vaccinations Europe is a world leader in controlling vaccine usually delivered in infancy9. preventable diseases3. However, there were outbreaks of measles and cases of diphtheria, pertussis, and Inequalities in access to childhood mumps in Europe in 2016, 2017, and 2018. immunisation persist. Like other medical Measles cases in Europe tripled between interventions, vaccination is subject to the 2017 and 20184. social gradient10, contributing to health inequalities11. Wealth distribution, maternal The mid-term review of the WHO/Europe education, place of residence, the sex of Vaccination Plan 2015-2020 found that the the child, and poverty are linked to levels region is not on track to reach its goal of of vaccination coverage12,13. It is important verification of measles and rubella elimination, to consider these factors when designing and is at risk of not reaching vaccination universal vaccination programmes that coverage targets5. respond to the needs of low socio-economic groups. Less than 0.5% of GDP is allocated to disease prevention programs and vaccine expenditure fall below 0.5% of healthcare spending in many of the European countries6. -

EQUINET WEBINAR SERIES on Equality, Diversity, and Non-Discrimination in Healthcare

EQUINET WEBINAR SERIES on Equality, Diversity, and Non-Discrimination in Healthcare Tackling systemic inequalities for a more egalitarian access to healthcare services 22, 24, 28, 30 June 2021 3. Healthcare services and systemic equality: Unpacking challenges 28/06/2021, 10.00-12.30 CEST A recent Eurobarometer survey showed that healthcare was by far the most important issue for the future of Europe according to Europeans. However, equality in the field of healthcare, despite its centrality to wellbeing, remains a relatively under-examined field in the work of equality bodies compared to fields such as employment or education. This is reflected by the lack of EU wide legislation that would cover the field of healthcare in national anti-discrimination legislation across all grounds, which indirectly affects the mandates of equality bodies throughout Europe. Due to these limitations, the mandates and powers of equality bodies among European countries greatly varies. The findings of the forthcoming Equinet perspective ‘Equality, Diversity, and Non-Discrimination in Healthcare’ prepared by Niall Crowley, points to obstacles faced by equality bodies in the field of healthcare. These barriers are for instance linked to the design of national healthcare systems, which often face an overall lack of resources and an uneven geographical spread of services, directly affecting access for the most marginalised groups. Other obstacles identified in Equinet’s perspective include the inherent complexity of healthcare systems requiring particular expertise from equality bodies and the power imbalances between patient and provider. The perspective points to the lack of attention to equality within healthcare systems signalling the lack of organisational equality infrastructures, capacity, and policies in healthcare provider organisations. -

Green Paper on Ageing Eurohealthnet’S Consultation Input, December 2020

Roadmap towards a European Commission’s Green Paper on Ageing EuroHealthNet’s consultation input, December 2020 In the context of demographic and socio-economic changes, particularly those related to ageing, key functions of public health - health promotion and prevention – should be central to European and national efforts to assess, prepare and act in a timely way to keep people healthy. To ensure the sustainability and affordability of health and social protection systems, it will be increasingly important that people can stay active and contribute to society for longer. The European Commission report on the impact of demographic changei correctly highlights regional inequalities in health outcomes and abilities to absorb the impact of demographic change. Future work on demographics must also address social and economic inequalities within countries and regions. We do not all age equally; people with lower levels of education and low-status jobs suffer more from the negative aspects of ageing more than others, and experience those aspects earlier. Europe will need a highly skilled and adaptable workforce in the future, however, the needs of those who cannot or have more difficulties up- or re-skill cannot be ignored if the EU does not wish to exacerbate existing inequalities and social instability. In recent years, a focus on rising healthcare costs – mostly due to the ageing population and the rise in non- communicable and chronic conditions, especially in high-income countries, has dominated the policy debate, whereas health as an investment for economic return has largely been absent from the discussion. This has been a focus for EuroHealthNet’s efforts in this field. -

The European Partnership for Health Equity and Wellbeing

EuroHealthNet. The European Partnership for Health Equity and Wellbeing Our Mission • Reducing Health Inequalities • Improve health - determinants of health Our Approach • Life course • Determinants of health • Sustainable Development Goals Where next? • Engagement EU policy • Funding • Integrating equity Opportunities for engagement • New Commissioner Portfolio and New • AIM: to have the Green Paper on Ageing prevention of • EPSCO conclusions and decade of Healthy frailty on EU & Ageing MS political agenda’s and • European Semester cycle in 2020 continue • Input to Action Plan on European Pillar cooperation Social Rights • Take forward SDGs 3 Opportunities for Engagement • Steering Group on Promotion and Prevention – continued funding for ADVANTAGE best actions • AIM: to maintain frailty high on EU & • Provide recommendations to ESF+ MS political programme committee and health agenda’s and working group continue cooperation • Make use of European Structural Support Services (25 billion) to reform long term care – MS applications every October 4 Funding Regional Development and Cohesion Policy • Policy Objective 4: A More Social Europe delivering on • Multiannual the European Pillar of Social Rights Financial European Social Fund Plus (101.2 billion) Framework 2021- 2027 – What is in • ESF +, including EU Health Programme and at least 25% there to fund will be allocated to fostering social inclusion further action on InvestEU – 4th policy window on social measures and preventing inequality frailty? HorizonEurope – taking forward SDGs and 5 mission areas Digital health? – beware of digital divide and health literacy among frail people 5 Financing Health Promoting Services An information guide Social Impact Investing Reduction in loneliness, Worcestershire, UK • Social Impact Costs £330,000 each year to support up to 430 Bonds older people (c. -

Healthy Ageing Project Healthy Ageing Be a Particularly Rapid Increase in the Number of Aims to Promote Healthy Ageing Among People People Aged 80 Years and Older

BY 2025 ABOUT one-third of Europe’s popula- Co-funded by the European Commission, the tion will be aged 60 years and over and there will three-year (2004–2007) Healthy Ageing project Healthy Ageing be a particularly rapid increase in the number of aims to promote healthy ageing among people people aged 80 years and older. The countries aged 50 years and over. It involves ten coun- A CHALLENGE FOR EUROPE of Europe must develop strategies to meet this tries, the World Health Organisation (WHO), the challenge. Promoting good health and active European Older People’s Platform (AGE) and societal participation among the older citizens EuroHealthNet. The goal is exchange of know- HEALTHY AGEING – will be crucial in these strategies. ledge and experience among the European TheHealthy Ageing – a Challenge for Europe Union Member States and EFTA-EEA countries. report presents an overview of interventions The main aims have been to review and analyse on ageing and health. It includes suggested existing data on health and ageing, to produce a recommendations to decision makers, NGOs report with recommendations and to develop and practitioners on how to get into action to a comprehensive strategy for implementation of promote healthy ageing among the growing the report findings and the recommendations. number of older people. The report also presents different countries’ A CHALLENGE FOR EUROPE policies/strategies for older people’s health, summaries of reviews on the effectiveness of interventions for later life, and a number of ex- amples on good practice projects promoting healthy ageing. Data about the health of older people is presented. -

Statement by Eurohealthnet at the 66Th Session of WHO Regional

Statement by EuroHealthNet at the 66th session of WHO Regional Committee for Europe on the topic: ‘Health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its relation to Health 2020’ (agenda item 5a) The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development offers new opportunities for health promotion to improve governance and ensure sustainable policy making while implementing its values, principles and approaches in a new global context. We welcome the initiative to support action in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and link with Health 2020 Strategy. Much needs to be done and can be facilitated by the UN Agenda 2030 which requires transformative processes to be undertaken globally and nationally to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Our extensive partnerships consist of (sub) national public health and health promotion authorities as well as of research institutes and strategic partners from other sectors. Many of our members are involved in developing and implementing the SDGs and also the WHO Health 2020 Strategy in their own countries or regions. As the leading European Partnership for improving health, equity and wellbeing, EuroHealthNet contributes with knowledge and experience, and shares our vision on what we want health promotion to achieve by 2030. We would like to highlight three priorities in relation with the proposed topic: 1. We need to move forward by promoting health in a rapidly changing world. We need to draw shared values regarding equity and well-being in modern settings while adapting continuously and acting on the realities we face. Equity, social justice, well-being and reducing health inequalities while building sustainable health systems are at the heart of Health 2020.