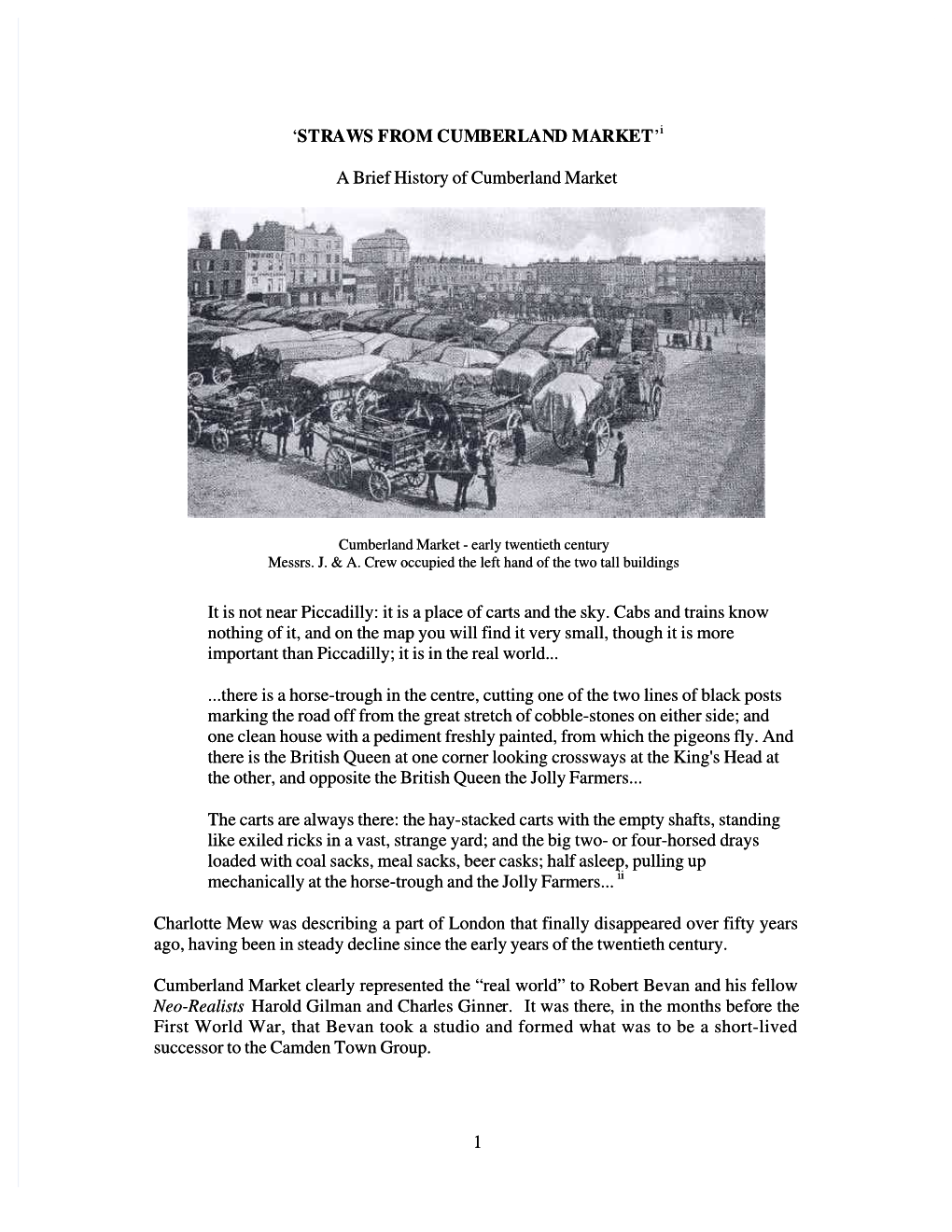

A Brief History of Cumberland Market It Is Not Near Piccadilly: It Is a Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auckland City Art Gallery

Frances Hodgkins 14 auckland city art gallery modern european paintings in new Zealand This exhibition brings some of the modern European paintings in New Zealand together for the first time. The exhibition is small largely because many galleries could not spare more paintings from their walls and also the conditions of certain bequests do not permit loans. Nevertheless, the standard is reasonably high. Chronologically the first modern movement represented is Impressionism and the latest is Abstract Expressionism, while the principal countries concerned are Britain and France. Two artists born in New Zealand are represented — Frances Hodgkins and Raymond Mclntyre — the former well known, the latter not so well as he should be — for both arrived in Europe before 1914 when the foundations of twentieth century painting were being laid and the earlier paintings here provide some indication of the milieu in which they moved. It is hoped that this exhibition may help to persuade the public that New Zealand is not devoid of paintings representing the serious art of this century produced in Europe. Finally we must express our sincere thanks to private owners and public galleries for their generous response to requests for loans. P.A.T. June - July nineteen sixty the catalogue NOTE: In this catalogue the dimensions of the paintings are given in inches, height before width JANKEL ADLER (1895-1949) 1 SEATED FIGURE Gouache 24} x 201 Signed ADLER '47 Bishop Suter Art Gallery, Nelson Purchased by the Trustees, 1956 KAREL APPEL (born 1921) Dutch 2 TWO HEADS (1958) Gouache 243 x 19i Signed K APPEL '58 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by the Contemporary Art Society, 1959 JOHN BRATBY (born 1928) British 3 WINDOWS (1957) Oil on canvas 48x144 Signed BRATBY JULY 1957 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by Auckland Gallery Associates, 1958 ANDRE DERAIN (1880-1954) French 4 LANDSCAPE Oil on canvas 21x41 J Signed A. -

Charles Ginner, A.R.A

THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com Charles Ginner, A.R.A. (Cannes 1878 – 1952 London) St. Just in Cornwall – A landscape with cottages Signed ‘C. GINNER’ (lower left) Pen and ink and watercolour on paper 9 ¾ x 11 ¾ in. (25 x 30 cm.) Provenance Gifted by the Artist to Mrs. Frank Rutter. The Fine Art Society, 1985. Henry Wyndham Fine Art Ltd, London. Private Collection. Exhibited London, St George's Gallery, Charles Ginner and Randolph Schwabe, March 1926 (details untraced). London, The Fine Art Society, Charles Ginner, 7th - 25th October 1985, cat. no.13, illustrated. Literature Charles Ginner, List of Paintings, Drawings, etc. of Charles Ginner, Book II, 1919-1924, p. 135. Primarily a townscape and landscape painter, Charles Ginner grew up in France where his father, a doctor, practised, but settled in London in 1910. He was heavily influenced by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin and Paul Cézanne. In 1909, Ginner visited Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he held his first one-person show, which helped to introduce post-Impressionism to South America. Thos Agnew & Sons Ltd, registered in England No 00267436 at 21 Bunhill Row, London EC1Y 8LP VAT Registration No 911 4479 34 THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com He was a friend of Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore and through them was drawn into Walter Sickert’s circle, becoming a founder member of the Camden Town Group in 1911 and the London Group in 1913. -

100 Years of the London Group the English Are an Essentially

Moving with the times: 100 years of the London Group The English are an essentially conservative people, their suspicion of anything new or innovative, unless it can be seen to have an immediate usefulness or purpose, innate. The arts, whose lifeblood depends on precisely those qualities, have not been immune to its effects, as the current plight of the arts in the school curriculum makes only too plain while the history of the visual arts in England, certainly over the last two hundred years or more and probably since the Reformation, has been dogged by its influence. The response has nearly always been the determination of a small group of artists to set up new societies or artistic groupings; first and foremost, of course, there was the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768 and, in the 19thC., when that institution had slipped back into full-blown academic conservatism, there were first the Pre-Raphaelites and then, in 1886, the New English Art Club on hand to stir things up once again. Indeed the history of English Modernism could, from this point on, almost be written in terms of constant reaction and renewal through such associations of artists, culminating in that heady period, just before the First World War when the flurry of new artistic associations stirred up by the response of younger artists to the Modernist revelations of Roger Fry’s two great French Post-Impressionist exhibitions of 1910 and 1912 – the Camden Town Group, the Fitzroy Street Group and the Allied Artists’ Association in particular - in their turn reacted against the by now largely establishment New English. -

Art Era Timeline 3 Early 20Th C – Modern

1 Art Movement Timeline Early 20th C Centuryentury till the start of Modern Art Time Line Art Movement Description Artists & examples Late 19th/ Early 20th Century Design Britain, Late 19th Arts and Crafts The Arts and Crafts Century Movement was a celebration of individual design and craftsmanship, William Morris , a book designer, 18341834----18961896 spearheaded the William Morris movement. He also produced stained glass, textiles and wallpaper and was a painter and writer. © Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com 04/2010 2 Late 19th Century to Art Nouveau Art Nouveau is an Early 20th Century elegant decorative art style characterized by intricate patterns of curving lines. Its origins somewhat 18601860----19391939 rooted in the British Alphonse Mucha Arts and Crafts Movement of William Morris , 18721872----18981898 Aubrey Beardsley 18621862----19181918 Gustav Klimt Louis Comfort Tiffany . 18481848----19331933 © Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com 04/2010 3 1880's to 1920's The Golden Age of The Golden Age of European artists: Illustration Illustration was a period of unprecedented excellence in book and magazine 18451845----19151915 illustration. Walter Crane Advances in technology permitted accurate and inexpensive reproduction of art. The public demand for new graphic art grew in this time. Edmund Dulac 18821882----19531953 18721872----18981898 Aubrey Beardsley 18671867----19391939 Arthur Rackham 18861886----19571957 © Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com 04/2010 4 The Golden Age of Kay Nielsen . Illustration American artists: 18531853----19111911 Howard Pyle 18821882----19451945 N.C. Wyeth 18701870----19661966 Maxfield Parrish 18771877----19721972 Frank Schoonover 18521852----19111911 Edwin Austin Abbey . © Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com 04/2010 5 1920's to 1930's Art Deco Art Deco is an elegant style of decorative art, design and architecture which began as a Modernist reaction against the Art 18981898----19801980 Nouveau style. -

Scarica La Lista in Formato

Artinvest2000, i principali movimenti artistici. http://www.artinvest2000.com Dalla lettera A alla G ASTRATTISMO Astrattismo tendenza artistica del XX Secolo. Abbandonando la rappresentazione mimetica del mondo esterno, trova in generale le sue ragioni nella riflessione sulle specificità della ricerca formale e della percezione visiva. Parallelamente allo sviluppo di una speculazione estetica tra positivismo e spiritualismo (K. Fiedler, Origine dell'attività artistica, 1887; W. Worringer, Astrazione e empatia, 1908), molti artisti tendono alla rifondazione del proprio campo d'azione attraverso lo studio degli elementi formali che costituiscono le fondamenta sintattiche del linguaggio visivo, innescando un processo di sempre più radicale semplificazione e scomposizione delle forme. Una tendenza del genere, complicata dall'interesse per il meccanismo dei procedimenti percettivi, sposta progressivamente in secondo piano o elimina del tutto ogni preoccupazione rappresentativa. Sono soprattutto il "Sintetismo" e il decorativismo simbolista e la stilizzazione "Art nouveau" carica di suggestioni irrazionali e vitalistiche. ad alimentare il terreno culturale sul quale, attorno al 1910, si sviluppano diverse tendenze astratte nell'ambito dei movimenti d'avanguardia tedesco, russo, ceco e ungherese. Loro antecedenti immediati sono i due grandi movimenti innovatori dell'inizio del secolo, "Fauvisme" e "Cubismo". A questa duplice matrice formale si collegano i due modi principali dell'astrattismo, entrambi cresciuti nella ricerca di un ordine e di -

The EY Exhibition. Van Gogh and Britain

Life & Times Exhibition The EY Exhibition and his monumental Van Gogh and Britain London: a Pilgrimage. Tate Britain, London, Whistler’s Nocturnes 27 March 2019 to 11 August 2019 and Constable’s country landscapes also made a VINCENT IN LONDON considerable impression London seems to have been the springboard on him. Yet he did not for Vincent van Gogh’s creative genius. He start painting until he trained as an art dealer at Goupil & Cie in had unsuccessfully tried The Hague, coming to the company’s Covent his hand at teaching and Garden office in 1873, aged 20. He lodged in preaching. South London, initially in Brixton, and for a He returned to the short time stayed at 395 Kennington Road, Netherlands at the age of just a few minutes from my old practice 23, where, in 1880, after in Lambeth Walk. He soaked up London further unsatisfactory life and loved to read Zola, Balzac, Harriet forays into theology and Beecher Stowe, and, above all, Charles missionary work, his Dickens. This intriguing exhibition opens art dealer brother Theo movingly with a version of L’Arlésienne encouraged him to start (image right), in which Dickens’s Christmas drawing and painting. Stories and Uncle Tom’s Cabin lie on the Van Gogh’s earliest table. paintings were almost He became familiar with the work of pastiches of Dutch British illustrators and printmakers, and landscape masters, but, as he absorbed Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), L’Arlésienne, 1890. Oil paint on canvas, 650 × also that of Gustav Doré (below is van 540 mm. -

“Uproar!”: the Early Years of the London Group, 1913–28 Sarah Macdougall

“Uproar!”: The early years of The London Group, 1913–28 Sarah MacDougall From its explosive arrival on the British art scene in 1913 as a radical alternative to the art establishment, the early history of The London Group was one of noisy dissent. Its controversial early years reflect the upheavals associated with the introduction of British modernism and the experimental work of many of its early members. Although its first two exhibitions have been seen with hindsight as ‘triumphs of collective action’,1 ironically, the Group’s very success in bringing together such disparate artistic factions as the English ‘Cubists’ and the Camden Town painters only underlined the fragility of their union – a union that was further threatened, even before the end of the first exhibition, by the early death of Camden Town Group President, Spencer Gore. Roger Fry observed at The London Group’s formation how ‘almost all artist groups’, were, ‘like the protozoa […] fissiparous and breed by division. They show their vitality by the frequency with which they split up’. While predicting it would last only two or three years, he also acknowledged how the Group had come ‘together for the needs of life of two quite separate organisms, which give each other mutual support in an unkindly world’.2 In its first five decades this mutual support was, in truth, short-lived, as ‘Uproar’ raged on many fronts both inside and outside the Group. These fronts included the hostile press reception of the ultra-modernists; the rivalry between the Group and contemporary artists’ -

The Centenary Open Installtion View, View, Installtion 2013 Is Now Over, and There Has Been a Record- Breaking Number of Entries This Year

e The London Group s CENTENARY OPEN 2013 14 May-7 June 2013 a e l e , Peter Clossick , Peter r Across The Road In 1930 the roof garden of London’s famous department store Selfridges was given over to a London Group sculpture exhibition where prestigious members such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth exhibited alongside the work of emerging artists. This is just one inclusive show in the s illustrious 100-year history of The London Group, the UK’s longest running artists’ collective. The London Group have a long tradition of supporting the work of emerging artists through their s flagship event, the biennial open. Historically, these shows were seen as exhibiting opportunities for visual makers who had been thought of as minority status artists: young art students, women artists and those making work without commercial gallery patronage. The golden age for the open submission came after the war. These exhibitions were huge. In the e November 1952 exhibition, 360 works came from open submission. Again in the 1980s the shows had very high status again with three large exhibitions at the Royal College of Art Gulbenkian Galleries. The 1990s Opens were held at the Concourse Gallery in the Barbican Centre with the Artsinform CoBiennialmmunicatio n1995s Ltd. Open Exhibition selected by five guest selectors, Robin Klassnik, Angela Flowers, r t. +44 (0)1273 488996 w. www.artsinJenniform.co .Lomax,uk Louisa Buck and William Ling. The last Open was held in 2011 and had a positive e. [email protected] on the careers of its winners as ever: Pipe Passage, 151b High Stret, Lewes, East Sussex, BN7 1XU Company No: 06392254 p “Winning the Arcadia Missa Prize was an honour and great surprise. -

Interior Scene, Attributed to an Unknown

The Courtauld Institute of Art Painting Pairs: Art History and Technical Study Interior Scene, by an unknown artist (after Harold Gilman) Chloé D’Hondt, MA History of Art Luz Vanasco, Postgraduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings 2018 – 2019 Table of contents LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT ................................................................................ 4 INTERIOR SCENE: INTRODUCTORY REMARKS ......................................................... 5 HAROLD GILMAN ................................................................................................................ 7 COMPARATIVE VISUAL ANALYSIS .............................................................................. 10 MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUE ....................................................................................... 13 HAROLD GILMAN ............................................................................................................................................. 13 INTERIOR SCENE VS. HAROLD GILMAN ........................................................................................................... 16 Support ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Ground ........................................................................................................................................................ -

The Camden Town Group Teachers' Pack

13 FEBRUARY – 5 MAY 2008 THE CAMDEN TOWN GROUP TEACHER & STUDENT NOTES BY SARA PAPPWORTH MODERN PAINTERS: THE CAMDEN TOWN GROUP Introduction The Camden Town Group was formed in 1911. Its artists employed a wide variety of styles but shared a common desire to explore everyday subjects using consciously modern painting techniques. This exhibition at Tate Britain provides the first major survey of the Camden Town Group for more than twenty years. It focuses on the key themes of their work and examines their lasting impact. The impetus for the Camden Town Group’s formation was Roger Fry’s highly influential exhibition Manet and the Post- Impressionists (1910–1911), where avant-garde continental artists, such as Gauguin, Van Gogh and Cézanne, were seen in Britain for the first time. This heralded a new spirit in British painting in which The Camden Town Group, briefly, led the way. Camden artists pursued greater modernism of style and subject matter. Many, such as Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, adopted the Post-Impressionists’ use of vivid, bright, pulsating colours, which were applied in dabs of thick, matt paint. They also displayed a strong awareness of the decorative potential of simplified forms and the startling impact of unpredictable compositions. Their subject matter challenged Edwardian propriety with its vision of gritty urban interiors, music halls, prostitutes, cityscapes and suburbia. They embraced the lives of ordinary, humdrum humanity, without the moral comment or specific narratives of Victorian convention. London in 1911 was a city of change in which the foundations of modern urban living were being established. -

Paul Gauguin: Monotypes

Paul Gauguin: Monotypes Paul Gauguin: Monotypes BY RICHARD S. FIELD published on the occasion of the exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art March 23 to May 13, 1973 PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART Cover: Two Marquesans, c. 1902, traced monotype (no. 87) Philadelphia Museum of Art Purchased, Alice Newton Osborn Fund Frontispiece: Parau no Varna, 1894, watercolor monotype (no. 9) Collection Mr. Harold Diamond, New York Copyright 1973 by the Philadelphia Museum of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-77306 Printed in the United States of America by Lebanon Valley Offset Company Designed by Joseph Bourke Del Valle Photographic Credits Roger Chuzeville, Paris, 85, 99, 104; Cliche des Musees Nationaux, Paris, 3, 20, 65-69, 81, 89, 95, 97, 100, 101, 105, 124-128; Druet, 132; Jean Dubout, 57-59; Joseph Klima, Jr., Detroit, 26; Courtesy M. Knoedler & Co., Inc., 18; Koch, Frankfurt-am-Main, 71, 96; Joseph Marchetti, North Hills, Pa., Plate 7; Sydney W. Newbery, London, 62; Routhier, Paris, 13; B. Saltel, Toulouse, 135; Charles Seely, Dedham, 16; Soichi Sunami, New York, 137; Ron Vickers Ltd., Toronto, 39; Courtesy Wildenstein & Co., Inc., 92; A. J. Wyatt, Staff Photographer, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Frontispiece, 9, 11, 60, 87, 106-123. Contents Lenders to the Exhibition 6 Preface 7 Acknowledgments 8 Chronology 10 Introduction 12 The Monotype 13 The Watercolor Transfer Monotypes of 1894 15 The Traced Monotypes of 1899-1903 19 DOCUMENTATION 19 TECHNIQUES 21 GROUPING THE TRACED MONOTYPES 22 A. "Documents Tahiti: 1891-1892-1893" and Other Small Monotypes 24 B. Caricatures 27 C. The Ten Major Monotypes Sent to Vollard 28 D. -

Complete Dissertation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository Table of Contents Page Title page 2 Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1 A brief biography of E J Power 8 Chapter 2 Post-war collectors of contemporary art. 16 Chapter 3 A Voyage of Discovery – Dublin, London, Paris, Brussels, 31 Copenhagen. Chapter 4 A further voyage to American and British Abstraction and Pop Art. 57 Conclusion 90 List of figures 92 Appendices 93 Bibliography 116 1 JUDGEMENT BY EYE THE ART COLLECTING LIFE OF E. J. POWER 1950 to 1990 Ian S McIntyre A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF EAST ANGLIA September 2008 2 Abstract Ian S McIntyre 2008 JUDGEMENT BY EYE The art collecting life of E J Power The thesis examines the pattern of art collecting of E J Power, the leading British patron of contemporary painting and sculpture in the period after the Second World War from 1950 to the 1970s. The dissertation draws attention to Power’s unusual method of collecting which was characterised by his buying of work in quantity, considering it in depth and at leisure in his own home, and only then deciding on what to keep or discard. Because of the auto-didactic nature of his education in contemporary art, Power acquired work from a wide cross section of artists and sculptors in order to interrogate the paintings in his own mind. He paid particular attention to the works of Nicolas de Stael, Jean Dubuffet, Asger Jorn, Sam Francis, Barnett Newman, Ellsworth Kelly, Francis Picabia, William Turnbull and Howard Hodgkin.