Beauvoir/Iribarren/Dodera Simone, Mujer Partida—A Shared Monologue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Thursday Volume 618 8 December 2016 No. 78 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 8 December 2016 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2016 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 349 8 DECEMBER 2016 350 Mr Speaker: I call James Cleverly. Not here. I assume House of Commons the hon. Gentleman was notified of the intended grouping. In that case, where on earth is the fella? Thursday 8 December 2016 Robert Neill (Bromley and Chislehurst) (Con): On the train. The House met at half-past Nine o’clock Mr Speaker: No doubt. PRAYERS Seema Kennedy: Can my hon. and learned Friend tell me a bit more about what the Crown Prosecution [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Service is doing to prosecute this type of offence in the north-west of England? Oral Answers to Questions The Solicitor General: I note my hon. Friend’s interest as a north-west MP, and I am happy to tell her that under the new modern slavery offence, eight charges ATTORNEY GENERAL were laid in the north-west region and eight offences in the Mersey-Cheshire region, plus other offences under older legislation, in the past year. Only last month three The Attorney General was asked— people were convicted of modern-day slavery and human Modern Slavery trafficking in Liverpool and were sentenced to a total of seven years and three months’ imprisonment. 1. Andrew Stephenson (Pendle) (Con): What steps the Government are taking to increase the number of Mr David Hanson (Delyn) (Lab): Many of the prosecutions for modern slavery. -

Rhodes Career Services Swine Flu Difffcult to Detect In

Vol. XCVI. NO. 7 The Why Hitler? Ask Professor ou’wester Hat eld. SNovember 11, 2009 e Weekly Student Newspaper of Rhodes College See Page 4 Rhodes Career Services Bill barely passes By Jasmine Gilstrap 103 and a new seminar titled Making It Counts “Ulti- Staff Writer mate Money Skills: College.” and sparks debate e question of what a one wants to be when “ e seminar was created to educate and empower they grow up is asked at an early age and is repeated college students to develop smart money management By Nene Baff ord was voted against 258-176. throughout years of education. Rhodes’ Career Services skills. is program prepares students with an under- News Editor Will Obama agree with the fi rst aids those who know the answer to the question as well standing of appropriate credit card use, student bank- e health care reform bill, amendment? Obama suggests that he as those in need of guidance. ing options, how to develop and follow a budget, and known as e Aff ordable Health Care is not comfortable with the abortion Career Services assists students with the career the importance of saving and emphasizes the impor- for America Act, was recently passed restrictions because they are chang- development process through self-assessment, career tance of how the choices students make about money in the House of Representatives, but ing the “status quo” on abortion and exploration, and career decision making. By providing while in college can have a direct impact on their future not without some minor issues. e limiting women’s insurance choices. -

EMORIES of Rour I EARS SERVICE

Under the Stars '"'^•Slfc- and Bars ,...o».... MEMORIEEMORIES OF FOUrOUR YI :EAR S SERVICE WITH TiaOR OGLETHORPES OF Jy WAWER A. CI^ARK, •,-'j-^j-rj,--:. j^rtrr.:f-'- H <^1 OR, MEMORIES OF FOUR YEARS SERVICE AVITH THE OGLETHORPES, OF AUGUSTA, GEORGIA BY WALTER A. CLARK, ORDERLY SERGEANT. AUGUSTA, GA Chronicle Printing Company. DEDICATION To the surviving members of the Oglethorpes, with whom I shared the dangers and hardships of soldier life and to the memory of those who fell on the firing line, or from ghostly cots in hospital Avards, with fevered lip and wasted forms, "drifted out on the unknown sea that rolls round all the Avorld," these memories are tenderly and afifectionatelv inscribed bv their old friend and comrade. PREFACE. For the gratification of my old comrades and in grate- hil memory of their constant kindness during all our years of comradeship these records have been written. The Avriter claims no special qualification for the task save as it may lie in the fact that no other survivor of the Company has so large a fund of material from which to draw for such a purpose. In addition to a war journal, whose entries cover all my four years service, nearly every letter Avritten by me from camp in those eventful years has been preserved. WHiatever lack, therefore, these pages may possess on other lines, they furnish at least a truth ful portrait of what I saw and felt as a soldier. It has beeen my purpose to picture the lights rather than the shadoAvs of our soldier life. -

Top Administrator Suspended for Alleged Discrimination Cable

A dark alley Not exactly the pla d want to meet THE CHRONICLE Anth-mvHonl-.nq'r e brilliant killer, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 1991 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA VOL. 86, NO. 102 Top administrator suspended for alleged discrimination By MICHAEL SAUL The investigation began after a tive statements in June 1990. down for the job on this basis," A top University administrator confidential source leaked a Brodie approved the investiga the transcript continued. "I see has been suspended for one memo from Harry Wyatt, di tion and the recommendations not much else I can do but month for allegedly violating the rector of planning and design for for punishment Monday evening. respect my supervisor's wishes University's non-discrimination the Medical Center, to the In "Mr. Nelson said that he was and turn him down." policy. dependent, a local weekly paper. uncomfortable with some of Mr. Nelson who has worked at the University officials announced Wyatt's position is subordinate to Burritt's mannerisms and felt University since 1972 was un Wednesday that Larry Nelson, Nelson's, and although Wyatt that there was a possibility that available for comment. assistant vice chancellor for was part of the interview and he was a homosexual," according Nelson does not feel he is health affairs and planning, will decision process, Nelson made to an excerpt from Wyatt's in guilty of discriminating, said face a one month suspension the final decision. ternal memo, published Feb. 20 Leonard Beckum, a member of without pay in addition to other Independent reporter Barry in the Independent. -

Annie Lennox OBE

Annie Lennox OBE Iconic Singer, Songwriter, Dedicated Acvist & Campaigner "You just decide what your values are in life and what you are going to do, and then you feel like you count, and that makes life worth living. It makes my life meaningful." Annie Lennox is one of the world's most renowned singer songwriters, formerly with the Eurythmics. She is celebrated as an innovator, an icon and a symbol of enduring excellence. Annie's music career is peerless with over 80 million record sales to date. TOPICS: IN DETAIL: Aid for Africa In 2007 Annie released her album, Songs of Mass Destrucon to crical acclaim. Fighting Aids The album featured SING a song featuring 23 of the world's most successful Why I am an HIV/AIDS Activist female superstars, invited by Annie to appear on the record to help draw Human Rights aenon to the HIV AIDS pandemic. The SING campaign connues to raise funds and awareness. In addion to the SING campaign, Annie is an Ambassador LANGUAGES: for UNAIDS, Oxfam, Nelson Mandela's 46664 Campaign, Amnesty Internaonal, The Brish Red Cross, London as well as supporng numerous other She presents in English. organisaons. In 2011 Annie received an OBE for her outstanding work and dedicaon as a humanitarian across the world. WHAT SHE OFFERS YOU: The most successful female Brish pop musician in history, Annie Lennox uses her unique voice to fight sgma and bring about change. A reless campaigner against HIV/AIDS in South Africa and its impact on women's and children's lives, she openly shares her experiences in South Africa and her fight against the HIV/ AIDS epidemic at presgious worldwide events. -

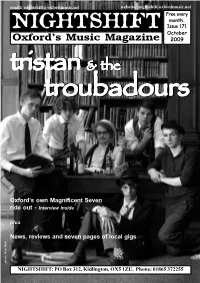

Issue 171.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 171 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 tristantristantristantristan &&& thethethe troubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadours Oxford’s own Magnificent Seven ride out - Interview inside plus News, reviews and seven pages of local gigs photo: Marc West photo: Marc NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THIS MONTH’S OX4 FESTIVAL will feature a special Music Unconvention alongside its other attractions. The mini-convention, featuring a panel of local music people, will discuss, amongst other musical topics, the idea of keeping things local. OX4 takes place on Saturday 10th October at venues the length of Cowley Road, including the 02 Academy, the Bullingdon, East Oxford Community Centre, Baby Simple, Trees Lounge, Café Tarifa, Café Milano, the Brickworks and the Restore Garden Café. The all-day event has SWERVEDRIVER play their first Oxford gig in over a decade next been organised by Truck and local gig promoters You! Me! Dancing! Bands month. The one-time Oxford favourites, who relocated to London in the th already confirmed include hotly-tipped electro-pop outfit The Big Pink, early-90s, play at the O2 Academy on Thursday 26 November. The improvisational hardcore collective Action Beat and experimental hip hop band, who signed to Creation Records shortly after Ride in 1990, split in outfit Dälek, plus a host of local acts. Catweazle Club and the Oxford Folk 1999 but reformed in 2008, still fronted by Adam Franklin and Jimmy Festival will also be hosting acoustic music sessions. -

Annie Lennox OBE Speaker Profile

Annie Lennox OBE Iconic Singer, Songwriter, Dedicated Activist & Campaigner CSA CELEBRITY SPEAKERS Annie Lennox is one of the world's most renowned singer songwriters, formerly with the Eurythmics. She is celebrated as an innovator, an icon and a symbol of enduring excellence. Annie's music career is peerless with over 80 million record sales to date. "You just decide what your values are in life and what you are going to do, and then you feel like you count, and that makes life worth living. It makes my life meaningful." Im Einzelnen Sprachen In 2007 Annie released her album, Songs of Mass Destruction to She presents in English. critical acclaim. The album featured SING a song featuring 23 of the world's most successful female superstars, invited by Annie to Möchten Sie mehr erfahren? appear on the record to help draw attention to the HIV AIDS Für ausführlichere Informationen rufen Sie uns bitte an oder pandemic. The SING campaign continues to raise funds and schicken Sie uns eine E-Mail. awareness. In addition to the SING campaign, Annie is an Ambassador for UNAIDS, Oxfam, Nelson Mandela's 46664 Wie können Sie die Rednerin buchen? Campaign, Amnesty International, The British Red Cross, London Per Telefon oder E-Mail. as well as supporting numerous other organisations. In 2011 Annie received an OBE for her outstanding work and dedication Beglaubigungsschreiben as a humanitarian across the world. 2011 Ihre Vorträge Annie received an OBE in the New Year's Honours List for her humanitarian work The most successful female British pop musician in history, Annie Women For Women International Making a Difference Award Lennox uses her unique voice to fight stigma and bring about The Daily Record "Entertaining Hero Award" change. -

Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Mhishi, Lennon Chido (2017) Songs of migration : experiences of music, place making and identity negotiation amongst Zimbabweans in London. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/26684 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Songs of Migration: Experiences of Music, Place Making and Identity Negotiation Amongst Zimbabweans in London Lennon Chido Mhishi Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Anthropology and Sociology 2017 Department of Anthropology and Sociology SOAS, University of London 1 I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

“Pop Artists Should BE Judged on Their Work, Not Their Lifestyle”

MOTION: SEPTEMBER 2009 POP “PoP ARTISTS ARTISTS SHOULD BE NAOMI TODD JUDGED ON THEIR WORK, NOT THEIR LIFesTYLE” DEBATING MATTERS DEBATOPITING MATTERCS GUIDETOPICS GUIDEwww.debatingmatters.comS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 of 7 NOTES Michael Jackson’s death in 2009 prompted much discussion over Introduction 1 how the pop-star should be remembered – as ‘Wacko Jacko’, the Key terms 1 tabloid figure famed for his erratic behaviour, extreme plastic surgery and accusations of child abuse, or as an extraordinary The pop artists debate in context 2 talent who produced an exceptional body of work over his Essential reading 4 musical career? [Ref: The Times]. The question is whether pop artists should be judged on their work, or on their behaviour and Backgrounders 5 lifestyle. Whilst many artists are celebrated for the work they produce, the coverage given to the likes of Pete Doherty and Amy Organisations 5 Winehouse suggests that their work is but the support act to In the news 6 their many personal dramas. [Ref: Independent] Is this focus on lifestyle damaging? Is it a necessary side-effect of many artists’ alleged status as role models for the young and impressionable? Are pop stars today victims of a celebrity culture, or do they have themselves to blame for becoming a part of it? Does focus on an artist’s lifestyle damage their work? KEY TERMS Celebrity culture Private Life The nature of fame Andy Warhol and the cult(ure) of personality DEBATING MATTERS © ACADEMY OF IDEAS LTD 2009 TOPIC POP ARTISTS: DEBATING MATTERS GUIDES “Pop artists should be judged on their work, not their lifestyle” WWW.DEBATINGMATTERS.COM THE POP ARTISTS DEBATE IN CONTEXT 2 of 7 NOTES Does focus on an artist’s lifestyle damage their Role models? work? One reason for the scrutiny of artists’ lifestyles is that they The death of Michael Jackson has also prompted debate over are widely regarded as role models for young people. -

Hail the Queen

ThE QLIEEN? BY TAMARA WINFREY HARRIS ILLUSTRATIONS RYIRANA DOUER What do our perceptions of Bejonce'sfeminism say about us? Who run the world? If entertainment domination is the litmus test, then all hail Queen Bey. Beyoncé. She who, in the last few months alone, whipped her golden lace-front and shook her booty fiercely enough to zap the power in the Superdome (electrical relay device, bah!); produced, directed, and starred in Life Is Buta Dream, HBO's most-watched documentary in nearly a decade; and launched the Mrs. Carter Show—the must-see concert of the summer. Beyoncé's success would seem to offer many reasons But some pundits are hesitant to award the for feminists to cheer. The performer has enjoyed singer feminist laurels. For instance, Anne Helen record-breaking career success and has taken con- Petersen, writer for the blog Celebrity Gossip, trol of a multimillion-dollar empire in a male-run Academic Style (and Bitch contributor), says, industry, while being frank about gender inequities "What bothers me—what causes such profound and the sacrifices required of women. She employs ambivalence—is the way in which [Beyoncé has] an all-woman band of ace musicians—the Sugar been held up as an exemplar of female power and, Mamas—that she formed to give girls more musical by extension, become a de facto feminist icon.... role models. And she speaks passionately about the Beyoncé is powerful. F-cking powerful. And that, power of female relationships. in truth, is what concerns me." SUMMER.13 I ISSUE NO.59 bítCh I 29 Petersen says the singer's lyrical feminism In a January 2013 Guardian article titled "Beyoncé: Being Photographed in Your swings between fantasy ("Run the World [Girls]") Underwear Doesn't Help Feminism," writer Hadley Freeman blasts the singer for posing and "bemoaning and satirizing men's inability to in the February issue of GQ "nearly naked in seven photos, including one on the cover in commit to monogamous relationships" ("Single which she is wearing a pair of tiny knickers and a man's shirt so cropped that her breasts Ladies"). -

AIDS, Orphan Care and the Family in Lesotho by Mary Ellen Block A

Infected Kin: AIDS, Orphan Care and the Family in Lesotho by Mary Ellen Block A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Social Work and Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elisha P. Renne, Co-Chair Associate Professor Karen M. Staller, Co-Chair Professor Gillian Feeley-Harnik Associate Professor Letha Chadiha Lecturer Holly Peters-Golden © Mary Ellen Block 2012 Ho bana le baholisi ba bona . ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I dedicate this dissertation to the babies and caregivers ( ho bana le baholisi ba bona ) of Mokhotlong who helped reveal to me the many challenges of the AIDS orphan crisis, and without whom this work would not be possible. From my earliest days in Mokhotlong, they opened their homes to me and shared with me their most personal and painful stories for reasons I cannot begin to imagine. People willingly and cheerfully gave me their time, entry into their private spaces and their friendship, and for that I am truly humbled and grateful. The MCS staff deserves special mention. The safe home bo’m’e (house mothers) were always welcoming, friendly and ready to laugh at my attempts at humor in Sesotho. I am particularly indebted to the outreach workers with whom I spent countless hours driving around the Lesotho countryside chatting, sleeping, and asking obvious and countless questions. For their knowledge, time and patience I am forever in their debt. To my trusted, wonderful and delightful research assistant, Ausi Ntsoaki, who drove hundreds of miles with me on the back of my dirt bike, who spent painstaking hours transcribing interviews with me, and who made every day in the field not only easier, but truly enjoyable. -

25 Years of the London Jazz Festival

MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay Published in Great Britain in 2017 by University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK as part of the Impact of Festivals project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, under the Connected Communities programme. impactoffestivals.wordpress.com ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book is an output of the Arts and Humanities Research Council collaborative project The Impact of Festivals (2015-16), funded under the Connected Communities Programme. The authors are grateful for the research council’s support. At the University of East Anglia, thanks to project administrators CONTENTS Rachel Daniel and Jess Knights, for organising events, picture 1 FOREWORD 50 CHAPTER 4. research, travel and liaison, and really just making it all happen JOHN CUMMING OBE, THE BBC YEARS: smoothly. Thanks to Rhythm Changes and CHIME European jazz DIRECTOR, EFG LONDON 2001-2012 research project teams for, once again, keeping it real. JAZZ FESTIVAL 50 2001: BBC RADIO 3 Some of the ideas were discussed at jazz and improvised music 3 INTRODUCTION 54 2002-2003: THE MUSIC OF TOMORROW festivals and conferences in London, Birmingham, Cheltenham, 6 CHAPTER 1. 59 2004-2007: THE Edinburgh, San Sebastian, Europe Jazz Network Wroclaw and THE EARLY YEARS OF JAZZ FESTIVAL GROWS Ljubljana, and Amsterdam. Some of the ideas and interview AND FESTIVAL IN LONDON 63 2008-2011: PAST, material have been published in the proceedings of the first 7 ANTI-JAZZ PRESENT, FUTURE Continental Drifts conference, Edinburgh, July 2016, in a paper 8 EARLY JAZZ FESTIVALS 69 2012: FROM FEAST called ‘The role of the festival producer in the development of jazz (CULTURAL OLYMPIAD) in Europe’ by Emma Webster.