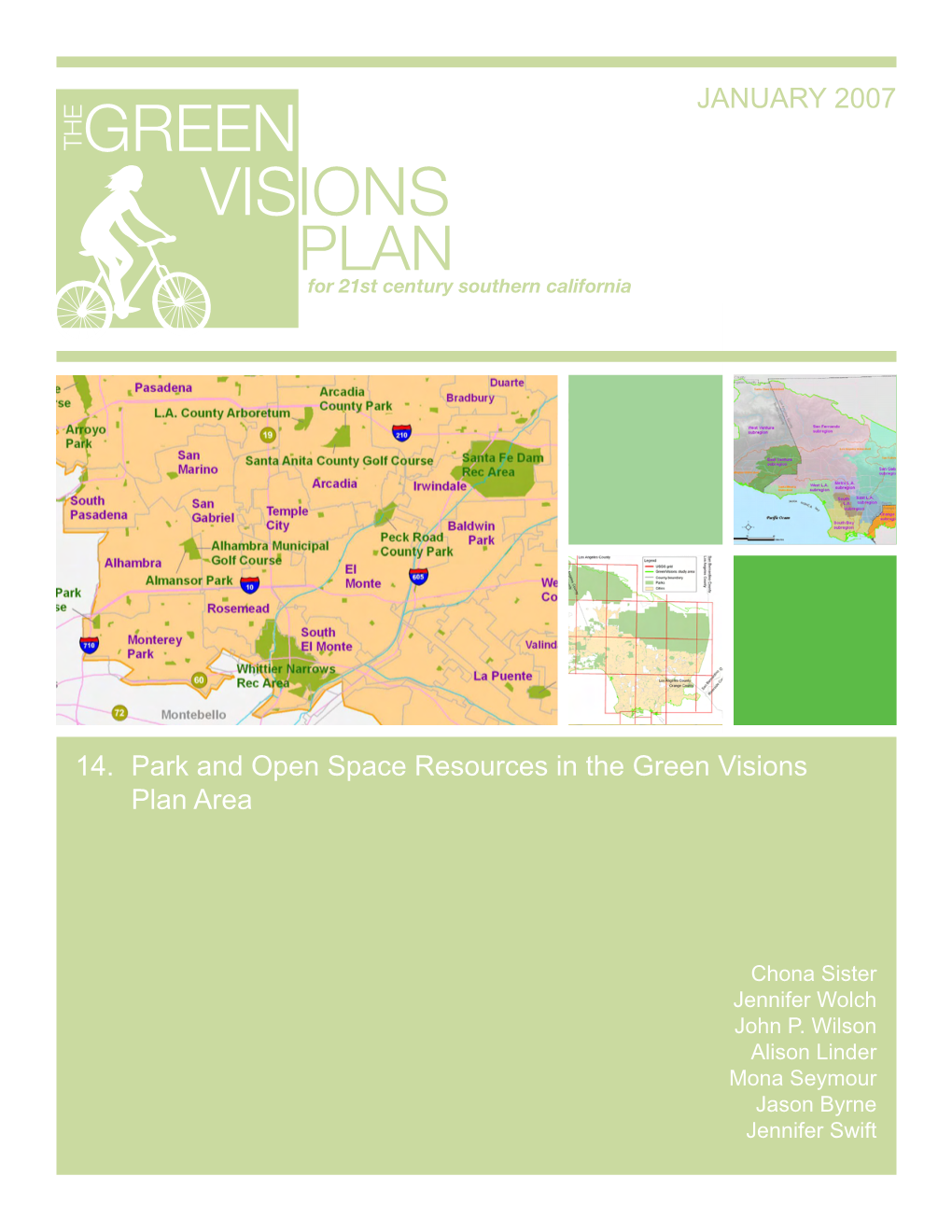

14. Park and Open Space Resources in the Green Visions Plan Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Tick Collection Results

Los Angeles County West Vector Control District 2021 TICK COLLECTION RESULTS Date Collection Location # of Ticks Result 1/5/21 Malibu Creek State Park - Mott Road 0 N/A 1/5/21 Malibu Creek State Park - Chaparral Trail 1 Negative 1/5/21 Tapia State Park - Spur Trail 4 Negative 1/5/21 Tapia State Park - Lower End Trail 0 N/A 1/6/21 Solstice Canyon Park - South Loop 0 N/A 1/6/21 Solstice Canyon Park - North Loop 0 N/A 1/7/21 Topanga State Park - Dead Horse Trail 5 Negative 1/7/21 Topanga State Park - Musch Trail 6 Negative 1/7/21 Will Rogers State Park - Backbone Trail 7 Negative 1/7/21 Will Rogers State Park - Betty Rogers Trail 7 Negative 1/8/21 Sullivan Canyon Park - Flood Control Trail 8 Negative 1/8/21 Sullivan Canyon Park - Canyon Trail 11 Negative 1/8/21 Franklin Canyon. Park - Hastain Trail 2 Negative 1/8/21 Franklin Canyon Park - Ranch Trail 3 Negative 1/11/21 Cheseboro Canyon - Modelo Trail 0 N/A 1/11/21 Paramount Ranch - Coyote Trail 0 N/A 1/12/21 Rocky Oaks State Park - Overlook Trail 0 N/A 1/12/21 Latigo Canyon - Eastside Backbone Trail 0 N/A 1/13/21 Malibu Creek State Park - Cage Creek Trail 3 Negative 1/13/21 Malibu - Piuma Backbone Trail 62 Negative 1/13/21 Palos Verdes Estates - Bluff Cove 7 Negative 1/13/21 Palos Verdes Estates - Apsley Path 1 Negative 1/13/21 Rolling Hills Estates - George F. -

GC 1359 CRA/LA Original Art on Paper Collection

GC 1359 CRA/LA Collection of Original Art on Paper Repository: Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Span Dates: 1981-2008; bulk is 2006-2008 Extent: 98 Pieces (3 ov boxes, mc and loose pieces) Language: English Conditions Governing Use: Permission to publish, quote or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder Conditions Governing Access: Research is by appointment only Preferred Citation: CRA/LA Collection of Original Art on Paper. Seaver Center for Western History Research, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Related Holdings: P-257 Chris Morland; P-258 Paul Slaughter Abstract: The CRA/LA Collection of Original Art on Paper consists primarily of photographs particularly silver gelatin and ambrotype prints. Watercolor and pastel; mixed media; linocut and block print; letterpress, serigraph; and cel vinyl on acetate. Subject matter and locale covers the city of Los Angeles, California. Seaver Center for Western History Research Scope and Content: The CRA/LA Collection of Original Art on Paper consists primarily of photographs particularly silver gelatin and ambrotype prints. Watercolor and pastel; mixed media; linocut and block print; letterpress, serigraph; and cel vinyl on acetate. Subject matter and locale covers the city of Los Angeles, California. Artists are William Acedo, Joyce Campbell, Carlos Figueroa, Cliff Garten, Daniel Gonzales, Raul Guerrero, Milano Kazanjian, Michael G. Levine, Chris Morland, Sonia Romero, John Smith, Neal Taylor with Elaine Fuess Parks, Pat Warner, and Ernesto Yerena. Background Note: The CRA/LA, a Designated Local Authority donated artwork to various southern California cultural institutions that were previously owned by the now-dissolved former agency, the Community Redevelopment Agency of the City of Los Angeles. -

Doggin' America's Beaches

Doggin’ America’s Beaches A Traveler’s Guide To Dog-Friendly Beaches - (and those that aren’t) Doug Gelbert illustrations by Andrew Chesworth Cruden Bay Books There is always something for an active dog to look forward to at the beach... DOGGIN’ AMERICA’S BEACHES Copyright 2007 by Cruden Bay Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Cruden Bay Books PO Box 467 Montchanin, DE 19710 www.hikewithyourdog.com International Standard Book Number 978-0-9797074-4-5 “Dogs are our link to paradise...to sit with a dog on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boring - it was peace.” - Milan Kundera Ahead On The Trail Your Dog On The Atlantic Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Gulf Of Mexico Beaches 6 Your Dog On The Pacific Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Great Lakes Beaches 0 Also... Tips For Taking Your Dog To The Beach 6 Doggin’ The Chesapeake Bay 4 Introduction It is hard to imagine any place a dog is happier than at a beach. Whether running around on the sand, jumping in the water or just lying in the sun, every dog deserves a day at the beach. But all too often dog owners stopping at a sandy stretch of beach are met with signs designed to make hearts - human and canine alike - droop: NO DOGS ON BEACH. -

FY17-18 Park Fee Annual Report

FOR INFORMATION ONLY CITY OF LOS ANGELES Department of Recreation and Parks November 7, 2018 TO: Board of Recreation and Parks Commissioners FROM: Michael A. Shull, General Manager SUBJECT: PARK FEE ANNUAL REPORT FOR FISCAL YEAR 2017-2018 SUMMARY On September 7, 2016, the City Council approved the new Park Dedication and Fee Update Ordinance (Park Fee Ordinance), Ordinance No. 184,505, and approved a Resolution relative to a General Plan Amendment to amend the Public Recreation Plan of the Service Systems Element of the City of Los Angeles General Plan. The Park Fee Ordinance implemented a new development impact fee that requires all new residential dwelling units to dedicate land, or pay a fee in-lieu, or provide a combination of land dedication and fee payment, for the purpose of acquiring, expanding, and improving park and recreational facilities for new residents. Pursuant to Los Angeles Municipal Code Section 12.33 1.2, within 180 days after the last day of each fiscal year, the Department of Recreation and Parks (RAP) shall report on each of the park and recreational facilities on which fees were committed in the last fiscal year ·and the appropriate date by which construction of the park and recreational facilities will commence and maintain accounts and prepare reports in accordance with the Mitigation Fee Act ( Government Code Section 66000 et seq.). Section 66006 of the Mitigation Fee Act requires that each local agency that imposes developmental impact fees prepare an annual report providing specific information on those fees. Section 66001 of the Mitigation Fee Act also requires that the local agency makes findings every five years with respect to the purpose and nexus of the imposed fee, the sources and amounts of all of funding anticipated to complete financing in incomplete improvements and the approximate dates on which the previously identified funding is expected to be deposited into the appropriate account or fund. -

Travel Summary

Travel Summary – All Trips and Day Trips Retirement 2016-2020 Trips (28) • Relatives 2016-A (R16A), September 30-October 20, 2016, 21 days, 441 photos • Anza-Borrego Desert 2016-A (A16A), November 13-18, 2016, 6 days, 711 photos • Arizona 2017-A (A17A), March 19-24, 2017, 6 days, 692 photos • Utah 2017-A (U17A), April 8-23, 2017, 16 days, 2214 photos • Tonopah 2017-A (T17A), May 14-19, 2017, 6 days, 820 photos • Nevada 2017-A (N17A), June 25-28, 2017, 4 days, 515 photos • New Mexico 2017-A (M17A), July 13-26, 2017, 14 days, 1834 photos • Great Basin 2017-A (B17A), August 13-21, 2017, 9 days, 974 photos • Kanab 2017-A (K17A), August 27-29, 2017, 3 days, 172 photos • Fort Worth 2017-A (F17A), September 16-29, 2017, 14 days, 977 photos • Relatives 2017-A (R17A), October 7-27, 2017, 21 days, 861 photos • Arizona 2018-A (A18A), February 12-17, 2018, 6 days, 403 photos • Mojave Desert 2018-A (M18A), March 14-19, 2018, 6 days, 682 photos • Utah 2018-A (U18A), April 11-27, 2018, 17 days, 1684 photos • Europe 2018-A (E18A), June 27-July 25, 2018, 29 days, 3800 photos • Kanab 2018-A (K18A), August 6-8, 2018, 3 days, 28 photos • California 2018-A (C18A), September 5-15, 2018, 11 days, 913 photos • Relatives 2018-A (R18A), October 1-19, 2018, 19 days, 698 photos • Arizona 2019-A (A19A), February 18-20, 2019, 3 days, 127 photos • Texas 2019-A (T19A), March 18-April 1, 2019, 15 days, 973 photos • Death Valley 2019-A (D19A), April 4-5, 2019, 2 days, 177 photos • Utah 2019-A (U19A), April 19-May 3, 2019, 15 days, 1482 photos • Europe 2019-A (E19A), July -

Community Health Needs Assessment 2019

Community Health Needs Assessment 2019 Sherman Oaks Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment, 2019 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 12 METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 Primary Data ....................................................................................................................................................... 13 Secondary Data ................................................................................................................................................... 13 HOSPITAL AREA DEFINITION .................................................................................................................................. 15 COMMUNITY PROFILE ............................................................................................................................................ 16 Demographic Data .............................................................................................................................................. 16 HEALTH STATUS IN SERVICE PLANNING AREA AND COMPARISON AREAS ............................................................. 22 Cancers .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Linkage Design for the Santa Monica-Sierra Madre Connection. Produced by South Coast Wildlands, Idyllwild, CA

South Coast Missing Linkages Project: A Linkage Design for the SanSantatatata MonicaMonica----SierraSierra Madre Connection © Andrew M. Harvey VisualJourneys.net Prepared by: Kristeen Penrod Clint R. Cabañero Dr. Paul Beier Dr. Claudia Luke Dr. Wayne Spencer Dr. Esther Rubin Dr. Raymond Sauvajot Dr. Seth Riley Denise Kamradt South Coast Missing Linkages ProjectProject:::: A Linkage Design for the SanSantata Monica ––– Sierra Madre Connection Prepared by: Kristeen Penrod Clint R. Cabañero Dr. Paul Beier Dr. Claudia Luke Dr. Wayne Spencer Dr. Esther Rubin Dr. Raymond M. Sauvajot Dr. Seth Riley Denise Kamradt June 2006 This report was made possible with financial support from the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, California State Parks, National Park Service, Resources Legacy Fund Foundation, The Wildlands Conservancy, The Resources Agency, U.S. Forest Service, California State Parks Foundation, Environment Now, Zoological Society of San Diego, and the Summerlee Foundation. Results and information in this report are advisory and intended to assist local jurisdictions, agencies, organizations, and property owners in making decisions regarding protection of ecological resources and habitat connectivity in the area. Produced by South Coast Wildlands: Our mission is to protect, connect anandd restore the rich natural heritage of thethe South CoCoastast Ecoregion through the establishment of a system of connected wildlands. Preferred Citation: Penrod, K., C. Cabañero, P. Beier, C. Luke, W. Spencer, E. Rubin, R. Sauvajot, S. Riley, and D. Kamradt. 2006. South Coast Missing Linkages Project: A Linkage Design for the Santa Monica-Sierra Madre Connection. Produced by South Coast Wildlands, Idyllwild, CA. www.scwildlands.org, in cooperation with National Park Service, Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, California State Parks, and The Nature Conservancy. -

March 13, 2015 To: Honorable Council Members

FORM GEN. 160 (Rev. 6-80) CITY OF LOS ANGELES INTER-DEPARTMENTAL CORRESPONDENCE Date: March 13, 2015 To: Honorable Council Members From: Gary Lee Moore, City Engineer Bureau of Engineering Subject: CITY SIDEWALK REPAIR PROGRAM STATUS UPDATE NO. 1 (COUNCIL FILE 14-0163-S4) This document is prepared in response to the CF 14-0163-S4 relative to the City Sidewalk Repair Program. Specifically, Council instructed the Bureau of Engineering (BOE) to report back on the status of implementation of the Sidewalk Repair Program, including any required policies, hiring of employees, utilization of contractors and amount of sidewalk repairs completed. Program Progress On February 3, 2015, the City Council approved implementation of a FY 2014-2015 Sidewalk Repair Program for repair of sidewalks adjacent to City facilities. BOE was established as the Program Manager. A kickoff meeting was held on February 9, 2015, and subsequent meetings have been held on a weekly basis. The meetings are well attended and include the Mayor’s Office, Board of Public Works (BPW), Bureau of Contract Administration (BCA), Bureau of Street Lighting (BSL), Bureau of Street Services (BSS), City Administrative Officer (CAO), Chief Legislative Analyst (CLA), Department of Recreation and Parks (RAP) and the Department of Transportation (DOT). BOE appreciates the participation and collaborative efforts that have taken place to start the Program, and the cooperation has allowed us to accomplish a great deal in a relatively short time frame. On February 10, 2015, BOE immediately began assessment of the list of City Facilities that were provided by each Department as requested by the CAO. -

Surveyla Survey Report Template

Historic Resources Survey Report San Pedro Community Plan Area Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources Prepared by: July 2012 Table of Contents Project Overview 1 SurveyLA Methodology Summary 1 Project Team 3 Survey Area 3 Designated Resources 9 Community Plan Area Survey Methodology 11 Summary of Findings 13 Summary of Property Types 13 Summary of Contexts and Themes 14 For Further Reading 31 Appendices Appendix A: Individual Resources Appendix B: Non-Parcel Resources Appendix C: Historic Districts & Planning Districts SurveyLA San Pedro Community Plan Area Project Overview This historic resources survey report (“Survey Report”) has been completed on behalf of the City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning’s Office of Historic Resources (OHR) for the SurveyLA historic resources survey of the San Pedro Community Plan Area (CPA). This project was undertaken from September 2011 to July 2012 by Historic Resources Group (HRG). This Survey Report provides a summary of the work completed, including a description of the survey area; an overview of the field methodology; a summary of relevant contexts, themes and property types; and complete lists of all surveyed resources. This Survey Report is intended to be used in conjunction with the SurveyLA Field Results Master Report (“Master Report”) which provides a detailed discussion of SurveyLA methodology and explains the terms used in this report and associated appendices. In addition, a Survey Results Map has been prepared which graphically illustrates the boundaries of the survey area and the location and type of all resources identified during the field surveys. -

Pacific Coast SNPL 2012 Breeding Survey with WA OR CA

2012 Summer Window Survey for Snowy Plovers on U.S. Pacific Coast with 2005-2011 Results for Comparison. Note: blanks indicate no survey was conducted. Total Adults 2012 Adult Breakdown REGION SITE OWNER 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 male fem. sex? Grays Harbor Copalis Spit State Parks 00000 00 00 0 Conner Creek State Parks 00000 00 00 0 Damon Point/Oyhut S. Parks, D. Nat R. F & W 500000 00 00 0 County Total 500000 00 00 0 Pacific Midway Beach Private, State Parks 23 25 22 12 16 18 22 11 65 0 Graveyard Shoalwater Indian Tribe 10 0 0 2 11 0 Leadbetter Point NWR USFWS, State Parks 9 42282926201215 10 4 1 South Long Beach Private 00000 County Total 32 67 50 42 42 38 34 28 17 10 1 Washington Total 37 67 50 42 42 38 34 28 17 10 1 Clatsop Fort Stevens State Park (Clatsop Spit) ACOE, OPRD 0 0 0 0 1 00 1 Necanicum Spit OPRD 0000 0 01 00 1 County Total 000000 02 00 2 Tillamook Nehalem Spit OPRD 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 00 0 Bayocean Spit ACOE 00000 00 00 0 Netarts Spit OPRD 000000 00 00 0 Sand Lake Spit (S) USFS 000000 00 00 0 Nestucca Spit OPRD 0000 0 0 00 0 County Total 000000 00 00 0 Lane Baker Beach/Sutton Creek USFS 0200 1 00 00 0 Sutton Cr./Siuslaw River N Jetty USFS 0 0 0 0 00 0 Siuslaw River S Jetty to Siltcoos USFS 4 40 0 Siltcoos Spits N & S USFS 11 18 16 11 17 18 18 22 11 10 1 County Total 11 20 16 11 17 19 18 26 15 10 1 Douglas Siltcoos-Tahkenitch (Dunes Overlook) USFS 9 2 19 7 6 19 39 42 22 20 0 Tahkenitch Spit N & S USFS 515035132716 11 0 Umpqua River S Jetty to Tenmile Spit USFS 0 11 10 12 57 0 County Total 14 3 24 7 20 24 62 81 43 38 0 Coos Tenmile Spits USFS 13 15 27 24 24 36 13 16 88 0 Coos Bay N Spit BLM, ACOE 27 27 26 30 41 38 39 52 35 17 0 Whiskey Run to Coquille River OPRD 0000 00 00 0 Bandon State Park to New River OPRD, Private, BLM 22 12 15 8 14 40 16 14 95 0 County Total 62 54 68 62 79 114 68 82 52 30 0 Curry New River to Floras Lake BLM, Private, County 13 14 17 25 24 1 20 15 96 0 Blacklock Point to Sixes River (C. -

A G E N D a S P E C I a L M E E T I N G BOARD of RECREATION and PARK COMMISSIONERS of the CITY of LOS ANGELES Monday, May

A G E N D A S P E C I A L M E E T I N G BOARD OF RECREATION AND PARK COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES Monday, May 17, 2010 at 9:30 a.m. EXPO Center (Formerly known as L.A. Swim Stadium) Community Hall Room 3980 S. Menlo Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90037 EVERY PERSON WISHING TO ADDRESS THE COMMISSION MUST COMPLETE A SPEAKER’S REQUEST FORM AT THE MEETING AND SUBMIT IT TO THE COMMISSION EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT PRIOR TO THE BOARD’S CONSIDERATION OF THE ITEM. PURSUANT TO COMMISSION POLICY, COMMENTS BY THE PUBLIC ON AGENDA ITEMS WILL BE HEARD ONLY AT THE TIME THE RESPECTIVE ITEM IS CONSIDERED, FOR A CUMULATIVE TOTAL OF UP TO FIFTEEN (15) MINUTES FOR EACH ITEM. ALL REQUESTS TO ADDRESS THE BOARD ON PUBLIC HEARING ITEMS MUST BE SUBMITTED PRIOR TO THE BOARD’S CONSIDERATION OF THE ITEM. COMMENTS BY THE PUBLIC ON ALL OTHER MATTERS WITHIN THE SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION OF THE BOARD WILL BE HEARD DURING THE “PUBLIC COMMENTS” PERIOD OF THE MEETING. EACH SPEAKER WILL BE GRANTED TWO MINUTES, WITH FIFTEEN (15) MINUTES TOTAL ALLOWED FOR PUBLIC PRESENTATION. 1. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES: Approval of the Minutes of the Meeting of May 5, 2010 2. GENERAL MANAGER’S REPORTS: 10-120 Rancho Cienega Sports Complex - Agreement with the Rob Dyrdek Foundation for a Gift Consisting of the Design and Construction of Skate Plaza Improvements, and the Naming of the Skate Plaza in Memory of Charmette Bonpua 10-121 Proposition 84 Statewide Park Program - Donation Agreement between the Department of Recreation and Parks and the Trust for Public Land of the Acquisition, Development, -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map