DISSECTING the CRIMINAL CORPSE Staging Post-Execution Punishment in Early Modern England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissection: a Fate Worse Than Death

Res Medica, Volume 21, Issue 1 Page 1 of 8 HISTORICAL ARTICLE Dissection: a fate worse than death Elizabeth F. Pond Year 3, MBBS Hull York Medical School Correspondence email: [email protected] Abstract The teaching of Anatomy in medical schools has significantly declined, and doubts have been raised over whether or not doctors of today are fully equipped with anatomical knowledge required to practice safely. The history of anatomy teaching has changed enormously over centuries, and donating your body to medical science after death is very different today, compared with the body snatching and exhumations of the 18th and 19th centuries. With stories of public outcry, theft and outright murder, the history of anatomical education is a fascinating one. History has made an abundance of significant anatomical discoveries, is it not fundamental that medical students today are aware of the great lengths that our peers went to in order to obtain such pioneering discoveries? Copyright Royal Medical Society. All rights reserved. The copyright is retained by the author and the Royal Medical Society, except where explicitly otherwise stated. Scans have been produced by the Digital Imaging Unit at Edinburgh University Library. Res Medica is supported by the University of Edinburgh’s Journal Hosting Service: http://journals.ed.ac.uk ISSN: 2051-7580 (Online) ISSN: 0482-3206 (Print) Res Medica is published by the Royal Medical Society, 5/5 Bristo Square, Edinburgh, EH8 9AL Res Medica, 2013, 21(1):61-67 doi: 10.2218/resmedica.v21i1.180 Pond, EF. Dissection: a fate worse than death Res Medica 2013, 21(1), pp.61-67 doi:10.2218/resmedica.v21i1.180 Pond EF. -

Workbook on Security: Practical Steps for Human Rights Defenders at Risk

WORKBOOK ON SECURITY: PRACTICAL STEPS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS AT RISK FRONT LINE DEFENDERS WORKBOOK ON SECURITY: PRACTICAL STEPS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS AT RISK FRONT LINE DEFENDERS Published by Front Line 2011 Front Line Grattan House, 2nd Floor Temple Road Blackrock Co Dublin Ireland Phone: +353 1 212 3750 Fax: +353 1 212 1001 Copyright © 2011 Front Line Cover illustration: Dan Jones This Workbook has been produced for the benefit of human rights defenders and may be quoted from or copied so long as the source/authors are acknowledged. Copies of this Workbook are available free online at www.frontlinedefenders.org (and will be available in English, Arabic, French, Russian and Spanish) To order a Workbook, please contact: [email protected] or write to us at the above address Price: €20 plus post and packing ISBN: 978-0-9558170-9-0 Disclaimer: Front Line does not guarantee that the information contained in this Workbook is foolproof or appropriate to every possible circumstance and shall not be liable for any damage incurred as a result of its use. Written by Anne Rimmer, Training Coordinator, Front Line and reviewed by an invaluable team of human rights defenders: Usman Hamid, International Centre for Transitional Justice and Kontras, Indonesia, Ana Natsvlishvili, Georgia and a HRD from the Middle East (name withheld for security reasons). Acknowledgements: This Workbook is based on the concepts introduced in the Protection Manual for Human Rights Defenders, Enrique Eguren/PBI BEO, and the updated New Protection Manual for Human Rights Defenders, Enrique Eguren and Marie Caraj, Protection International. We are grateful to Protection International for permission to reproduce extracts from the New Protection Manual for Human Rights Defenders. -

Alumni @ Large

Colby Magazine Volume 98 Issue 2 Summer 2009 Article 10 July 2009 Alumni @ Large Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Recommended Citation (2009) "Alumni @ Large," Colby Magazine: Vol. 98 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol98/iss2/10 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. alumni at large 1920s-30s Meg Bernier Boyd Colby College Reunion at Reunion Office of Alumni Relations Waterville, ME 04901 1940 Ernest C. Marriner Jr. [email protected] 1941 Meg Bernier Boyd [email protected] 1942 Meg Bernier Boyd [email protected] Margaret Campbell Timberlake keeps active by line dancing every week and going on occasional trips. Y Walter Emery has travel plans of his own. In early fall he hopes to motor to New Brunswick to visit relatives, and, later in the year, he heads for Chapel Hill, N.C., to celebrate Thanksgiving with his niece and nephew. 1944 Josephine Pitts McAlary [email protected] PHOTO BY JIM EVANS We have made it to our 65th reunion! No Janet Deering Bruen ’79, left, and Betsy Powley Wallingford ’54 embrace during the parade of classes at small accomplishment. As I write this I have Reunion 2009, June 4-7. A reunion photo gallery is online at www.colby.edu/reunion. no idea how many of the Class of 1944 will make it to the June reunion. -

EL SALVADOR the Spectre of Death Squads

EL SALVADOR The spectre of death squads INTRODUCTION The spectre of death squads has come back to the fore of public life in El Salvador with the recent appearance of clandestine groups such as the Fuerza Nacionalista Mayor Roberto D’Aubuisson (FURODA), Nationalist Force Major Roberto D’Aubuisson. Their attacks, including death threats against public figures, media people and religious leaders among others have caused growing concern and outrage at national and international level. Death squads and paramilitary groups were responsible for the systematic secret murder, torture and “disappearance” of suspected government opponents during the 1980s and early 1990s and benefitted from total impunity. There was the hope that they would be held accountable and cease to exist as a result of the 1992 Peace Accords and corresponding commitments by the Salvadorean authorities and support of the international community to improve the human rights situation. There was, in fact, a gleam of hope after the end of the war when there was a significant decrease in the number of serious human rights violations, particularly “disappearances”. But death threats by clandestine groups against political and other activists persisted, and sporadic killings and attempted assassinations bearing the hallmarks of death squads were carried out after the signing of the accords. Amnesty International believes that the threat of a return of death squads in El Salvador will only be removed when a special investigation into their activities - both past and present - is carried out, and all those found responsible are brought to justice. BACKGROUND The Chapultepec Accords, signed on 16 January 1992, ended 12 years of armed conflict between the government and the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN), a non-governmental entity. -

AVMA Guidelines for the Depopulation of Animals: 2019 Edition

AVMA Guidelines for the Depopulation of Animals: 2019 Edition Members of the Panel on Animal Depopulation Steven Leary, DVM, DACLAM (Chair); Fidelis Pharmaceuticals, High Ridge, Missouri Raymond Anthony, PhD (Ethicist); University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, Alaska Sharon Gwaltney-Brant, DVM, PhD, DABVT, DABT (Lead, Companion Animals Working Group); Veterinary Information Network, Mahomet, Illinois Samuel Cartner, DVM, PhD, DACLAM (Lead, Laboratory Animals Working Group); University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama Renee Dewell, DVM, MS (Lead, Bovine Working Group); Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Patrick Webb, DVM (Lead, Swine Working Group); National Pork Board, Des Moines, Iowa Paul J. Plummer, DVM, DACVIM-LA (Lead, Small Ruminant Working Group); Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Donald E. Hoenig, VMD (Lead, Poultry Working Group); American Humane Association, Belfast, Maine William Moyer, DVM, DACVSMR (Lead, Equine Working Group); Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine, Billings, Montana Stephen A. Smith, DVM, PhD (Lead, Aquatics Working Group); Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia Andrea Goodnight, DVM (Lead, Zoo and Wildlife Working Group); The Living Desert Zoo and Gardens, Palm Desert, California P. Gary Egrie, VMD (nonvoting observing member); USDA APHIS Veterinary Services, Riverdale, Maryland Axel Wolff, DVM, MS (nonvoting observing member); Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW), Bethesda, Maryland AVMA Staff Consultants Cia L. Johnson, DVM, MS, MSc; Director, Animal Welfare Division Emily Patterson-Kane, PhD; Animal Welfare Scientist, Animal Welfare Division The following individuals contributed substantively through their participation in the Panel’s Working Groups, and their assistance is sincerely appreciated. Companion Animals—Yvonne Bellay, DVM, MS; Allan Drusys, DVM, MVPHMgt; William Folger, DVM, MS, DABVP; Stephanie Janeczko, DVM, MS, DABVP, CAWA; Ellie Karlsson, DVM, DACLAM; Michael R. -

Stillbirth and Intrauterine Fetal Death: Factors Affecting Determination of Cause Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Stillbirth and intrauterine fetal death: factors affecting determination of cause of death at autopsy J. Man*†, J. C. Hutchinson*†, A.E.P. Heazell‡, M. Ashworth*, S. Levine § and N. J. Sebire*† *Department of Histopathology, Camelia Botnar Laboratories, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK; †University College London, Institute of Child Health, London, UK; ‡Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Manchester University, Manchester, UK; §Department of Histopathology, St George’s Hospital, London, UK Correspondence to: Prof. N. J. Sebire, Department of Histopathology, Level 3 Camelia Botnar, Laboratories, Great Ormond Street Hospital, Great Ormond Street, London WC1N 3JH, UK (e-mail: [email protected]) Short title: Cause of stillbirth and IUFD KEYWORDS: ethnicity; maternal age; miscarriage; obesity; stillbirth 1 +A: Abstract Objectives There have been many attempts to classify cause of death in stillbirth, all such systems being subjective, allowing for significant observer bias, making accurate comparisons between systems challenging. The aim of this study was to examine factors relating to determination of cause of death by using a large dataset from two specialist centres, in which observer bias has been reduced by objectively classifying findings and assigning causes of death based on predetermined criteria. Methods Detailed autopsy reports from intrauterine fetal deaths (IUFD) during 2005- 2013 in the second and third trimesters were reviewed and findings entered into a specially designed database, in which cause of death (CoD) was assigned using predefined objective criteria. Data regarding CoD categories and factors affecting determination of CoD were analysed through queries and statistical tests run using Microsoft Access, Excel, Graph Pad Prism and StatsDirect, with Mann–Whitney U-test and comparison of proportions testing as appropriate. -

Talking Books Catalogue

Aaronovitch, Ben Rivers of London My name is Peter Grant and until January I was just another probationary constable in the Metropolitan Police Service. My only concerns in life were how to avoid a transfer to the Case Progression Unit and finding a way to climb into the panties of WPC Leslie May. Then one night, I tried to take a statement from a man who was already dead. Ackroyd, Peter The death of King Arthur An immortal story of love, adventure, chivalry, treachery and death brought to new life for our times. The legend of King Arthur has retained its appeal and popularity through the ages - Mordred's treason, the knightly exploits of Tristan, Lancelot's fatally divided loyalties and his love for Guenever, the quest for the Holy Grail. Adams, Jane Fragile lives The battered body of Patrick Duggan is washed up on a beach a short distance from Frantham. To complicate matters, Edward Parker, who worked for Duggan's father, disappeared at the same time. Coincidence? Mac, a police officer, and Rina, an interested outsider, don't think so. Adams,Jane The power of one Why was Paul de Freitas, a games designer, shot dead aboard a luxury yacht and what secret was he protecting that so many people are prepared to kill to get hold of? Rina Martin takes it upon herself to get to the bottom of things, much to the consternation of her friend, DI McGregor. ADICHIE, Chimamanda Ngozi Half of a Yellow Sun The setting is the lead up to and the course of Nigeria's Biafra War in the 1960's, and the events unfold through the eyes of three central characters who are swept along in the chaos of civil war. -

The 9Th SIDS International Conference Program and Abstracts

Program and Abstracts The 9th SIDS The9th International Conference SIDS International June 1-4 2006 in YOKOHAMA Conference June 1-4 2006 in YOKOHAMA www.sids.gr.jp Co-sponsored by The Japan SIDS Research Society and SIDS Family Association Japan Meeting with the International Stillbirth Alliance (ISA) and the International Society for the Study and Prevention of Infant Deaths (ISPID) Program and Abstracts Secretariat PROTECTING LITTLE LIVES, PROVIDING A GUIDING LIGHT FOR FAMILIES General lnquiry : SIDS Family Association Japan 6-20-209 Udagawa-cho, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-0042, Japan Phone/Fax : +81-3-5456-1661 Email : [email protected] Registration Secretariat : c/o Congress Corporation Kosai-kaikan Bldg., 5-1 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-8481, Japan Phone : +81-3-5216-5551 Fax : +81-3-5216-5552 Email : [email protected] Federation of Pharmaceutical WAM Manufacturers' Associations of JAPAN The 9th SIDS International Conference Program and Abstracts Table of Contents Welcome .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Greeting from Her Imperial Highness Princess Takamado ................................ 2 Thanks to our Sponsors!.............................................................................................................. 3 Access Map ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Floor Plan ............................................................................................................................................... -

Bury St Edmunds Walking Tour Final

Discovering Bury St Edmunds: A Walking Guide A step by step walking guide to Bury St Edmunds; estimated walking time: 2 hours Originally published: http://www.burystedmunds.co.uk/bury-st-edmunds-walk.html Bury St Edmunds is a picturesque market town steeped in history. Starting in the Ram Meadow car park, the following walk takes you on a circular route past the town's main sights and shops, with a few curios thrown in for good measure. At a leisurely pace it should take approximately 2 hours to complete. Bury St Edmunds car parks charge every day of the week, but are cheaper on Sundays. There are public toilets at the car park. A market takes over the centre of town every Wednesday and Saturday throughout the year. Abbot's Bridge From the car park, face the cathedral tower in the distance, and head through the courtyard of the Fox pub and out on to Mustow Street. Cross the road and turn right to find Abbot's Bridge, which dates back to the 12th century, and originally linked Eastgate Street with the Abbey's vineyard on the opposite bank of the river Lark. Beside this, you can still see the Keeper's cell, from which he would have operated the portcullis which protected the Abbey from unwanted visitors. The Aviary A little further along Mustow Street, enter the Abbey gardens on your left. The information board in front of you includes the current opening hours of the Abbey grounds, which vary with the changing seasons. Head straight up the path, and fork right at the first opportunity, you will find the aviary, and beyond this duck under the archway to enter the sensory garden. -

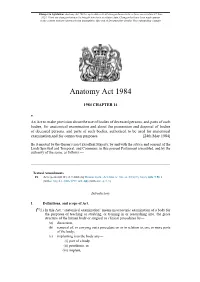

Anatomy Act 1984 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 21 June 2021

Changes to legislation: Anatomy Act 1984 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 21 June 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Anatomy Act 1984 1984 CHAPTER 14 F1 An Act to make provision about the use of bodies of deceased persons, and parts of such bodies, for anatomical examination and about the possession and disposal of bodies of deceased persons, and parts of such bodies, authorised to be used for anatomical examination,and for connection purposes. [24th May 1984] Be it enacted by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— Textual Amendments F1 Act repealed (E.W.) (1.9.2006) by Human Tissue Act 2004 (c. 30), ss. 59(8)(9), 60(2), Sch. 7 Pt. 1 (with s. 58); S.I. 2006/1997, art. 3(2) (with arts. 4, 7, 8) Introductory 1 Definitions, and scope of Act. [F2(1) In this Act, “anatomical examination” means macroscopic examination of a body for the purposes of teaching or studying, or training in or researching into, the gross structure of the human body or surgical or clinical procedures by— (a) dissection, (b) removal of, or carrying out a procedure on or in relation to, one or more parts of the body, (c) implanting into the body any— (i) part of a body, (ii) prosthesis, or (iii) implant, 2 Anatomy Act 1984 (c. -

Human Remains and Identification

Human remains and identification HUMAN REMAINS AND VIOLENCE Human remains and identification Human remains Human remains and identification presents a pioneering investigation into the practices and methodologies used in the search for and and identification exhumation of dead bodies resulting from mass violence. Previously absent from forensic debate, social scientists and historians here Mass violence, genocide, confront historical and contemporary exhumations with the application of social context to create an innovative and interdisciplinary dialogue. and the ‘forensic turn’ Never before has a single volume examined the context of motivations and interests behind these pursuits, each chapter enlightening the Edited by ÉLISABETH ANSTETT political, social, and legal aspects of mass crime and its aftermaths. and JEAN-MARC DREYFUS The book argues that the emergence of new technologies to facilitate the identification of dead bodies has led to a ‘forensic turn’, normalizing exhumations as a method of dealing with human remains en masse. However, are these exhumations always made for legitimate reasons? And what can we learn about societies from the way in which they deal with this consequence of mass violence? Multidisciplinary in scope, this book presents a ground-breaking selection of international case studies, including the identification of corpses by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the resurfacing ANSTETTand of human remains from the Gulag and the sites of Jewish massacres from the Holocaust. Human remains -

Opy of BO Much of the Said Plans, Sections, and Books

5046 «opy of BO much of the said plans, sections, and cham, Altringham, Hale, Halebarns, Ashley, Ring- books of reference as relates to each of the way, Ring way-within-Hale, Lindow, Northcliffe, parishes hereinbefore mentioned, from, in, through, Bollin-cum-Norcliff, Mobberley, Wilmslow, Ful- or into which the said railways, branch railway, shaw, Pownall F6e, Styal, Stanilands, Morley, ferry, and works will pass or be situate, will be Bollin Fee, Hough and Deanmw, all in the county deposited with the parish clerk of each such of Chester. parish.—Dated this fifth day of November 1845, And also to make and maintain a branch rail- Savery, Clark, and Co., Bristol, Solicitors. way, with all proper works and conveniences con- nected therewith and approaches thereto, diverging in an easterly direction from the said in- Lancashire, Cheshire, and Staffordshire Junction tended main line of railway firstly herein- Railway. before-mentioned, at a point in the township of Carington, in the parish of Bowdon, in the OTICE is hereby given, that application ia county of Chester, and terminating at and by a N intended to be made to Parliament in the junction with the Manchester and Birmingham ensuing session, for an Act or Acts to make and Railway, at a point in the township of Cheadle maintain a railway, with all proper works and Moseley, in the parish of Cheadle, in the county conveniences connected therewith, and approaches of Chester, there to communicate with the branch thereto, commencing by a junction with, or from railway from the said Manchester