EXPLORING CHINATOWN Past and Present This Booklet Was Produced in Conjunction with a EDGED BETWEEN Tour Held on April 17, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail Banking Announcement

Frequently asked questions 26 May 2021 What the repositioning of the HSBC USA Wealth and Personal Banking business means for our customers, here and abroad Why did HSBC take this action? In February 2020, we set out a plan to shift our business strategy in the United States to maximize the connection between our clients and our world-class international network. Our primary business will be a wholesale bank focused on the international needs of clients. We are renewing our emphasis on the US$5 trillion international wealth management opportunity from globally mobile and affluent individuals in the United States. Is HSBC exiting the United States? No, HSBC is not exiting its US business. We aim to be the leading international bank in the United States and are focused on what we do best – connecting Americans to a world of opportunity and bringing cross-border business and investment to the United States. We will continue to provide banking services not only to our wholesale banking clients, but also to our Premier, Jade and Private Banking customers. I have personal accounts at HSBC and I’m in the United States. How will these agreements affect me? Upon completion of the transactions, the accounts of in-scope customers will be transferred to Citizens or Cathay Bank. We thank those customers for their business and will ensure the transfer occurs with as minimum disruption as possible. Premier, Jade, Private Banking and other clients who will remain HSBC customers are in the process of being transitioned to one of our new 20-25 Wealth Centers. -

Pft Pittsburgh Picks! Aft Convention 2018

Pittsburgh Federation of Teachers PFT PITTSBURGH PICKS! AFT CONVENTION 2018 Welcome to Pittsburgh! The “Front Door” you see above is just a glimpse of what awaits you in the Steel City during our national convention! Here are some of our members’ absolute favorites – from restaurants and tours, to the best views, shopping, sights, and places to see, and be seen! Sightseeing, Tours & Seeing The City Double Decker Bus Just Ducky Tours Online booking only Land and Water Tour of the ‘Burgh Neighborhood and City Points of Interest Tours 125 W. Station Square Drive (15219) Taste of Pittsburgh Tours Gateway Clipper Tours Online booking only Tour the Beautiful Three Rivers Walking & Tasting Tours of City Neighborhoods 350 W. Station Square Drive (15219) Pittsburgh Party Pedaler Rivers of Steel Pedal Pittsburgh – Drink and Don’t Drive! Classic Boat Tour 2524 Penn Avenue (15222) Rivers of Steel Dock (15212) City Brew Tours Beer Lovers: Drink and Don’t Drive! 112 Washington Place (15219) Culture, Museums, and Theatres Andy Warhol Museum Pittsburgh Zoo 117 Sandusky Street (15212) 7370 Baker Street (15206) Mattress Factory The Frick Museum 500 Sampsonia Way (15212) 7227 Reynolds Street (15208) Randyland Fallingwater 1501 Arch Street (15212) Mill Run, PA (15464) National Aviary Flight 93 National Memorial 700 Arch Street (15212) 6424 Lincoln Highway (15563) Phipps Conservatory Pgh CLO (Civic Light Opera) 1 Schenley Drive (15213) 719 Liberty Avenue 6th Fl (15222) Carnegie Museum Arcade Comedy Theater 4400 Forbes Avenue (15213) 943 Penn Avenue (15222) -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

Cathay General Bancorp Contact: Heng W

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For: Cathay General Bancorp Contact: Heng W. Chen 777 N. Broadway (626) 279-3652 Los Angeles, CA 90012 CATHAY GENERAL BANCORP AND ASIA BANCSHARES INC. COMPLETE MERGER LOS ANGELES – August 3, 2015 – Cathay General Bancorp (NASDAQ: CATY), the holding company for Cathay Bank, announced today that it completed its merger with Asia Bancshares, Inc. at the end of the day on July 31, 2015. As a result of the transaction, Asia Bancshares, Inc. has been merged with and into Cathay General Bancorp, and Asia Bank has been merged with and into Cathay Bank. The completion of the merger results in a combined financial institution with total assets of approximately $12.4 billion and deposits of approximately $9.8 billion, 57 branches operating in nine states, and a presence in three overseas locations. Under the terms of the merger, Cathay General Bancorp is issuing 2.58 million shares of its common stock and paying $57.0 million in cash for all of the issued and outstanding shares of Asia Bancshares stock, valuing the merger at approximately $139.9 million, based on Cathay General Bancorp’s closing price on July 31, 2015. Based on properly and timely submitted and accepted elections, the stock consideration of 3.2134 shares of Cathay common stock per share of Asia Bancshares was over-subscribed by Asia Bancshares shareholders and subject to proration. As a result, approximately 36% of the shares of Asia Bancshares that were subject to stock elections will receive cash consideration of $86.76 per share of Asia Bancshares. Asia Bancshares shareholders who elected cash and those shareholders who failed to submit elections on a timely basis will receive cash consideration of $86.76 per share of Asia Bancshares. -

Chinatown and Urban Redevelopment: a Spatial Narrative of Race, Identity, and Urban Politics 1950 – 2000

CHINATOWN AND URBAN REDEVELOPMENT: A SPATIAL NARRATIVE OF RACE, IDENTITY, AND URBAN POLITICS 1950 – 2000 BY CHUO LI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor D. Fairchild Ruggles, Chair Professor Dianne Harris Associate Professor Martin Manalansan Associate Professor Faranak Miraftab Abstract The dissertation explores the intricate relations between landscape, race/ethnicity, and urban economy and politics in American Chinatowns. It focuses on the landscape changes and spatial struggles in the Chinatowns under the forces of urban redevelopment after WWII. As the world has entered into a global era in the second half of the twentieth century, the conditions of Chinatown have significantly changed due to the explosion of information and the blurring of racial and cultural boundaries. One major change has been the new agenda of urban land planning which increasingly prioritizes the rationality of capital accumulation. The different stages of urban redevelopment have in common the deliberate efforts to manipulate the land uses and spatial representations of Chinatown as part of the socio-cultural strategies of urban development. A central thread linking the dissertation’s chapters is the attempt to examine the contingent and often contradictory production and reproduction of socio-spatial forms in Chinatowns when the world is increasingly structured around the dynamics of economic and technological changes with the new forms of global and local activities. Late capitalism has dramatically altered city forms such that a new understanding of the role of ethnicity and race in the making of urban space is required. -

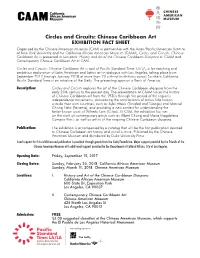

Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean

Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean Art EXHIBITION FACT SHEET Organized by the Chinese American Museum (CAM) in partnership with the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University and the California African American Museum (CAAM), Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean Art is presented in two parts: History and Art of the Chinese Caribbean Diaspora at CAAM and Contemporary Chinese Caribbean Art at CAM. Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean Art is part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, a far-reaching and ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles, taking place from September 2017 through January 2018 at more than 70 cultural institutions across Southern California. Pacific Standard Time is an initiative of the Getty. The presenting sponsor is Bank of America. Description: Circles and Circuits explores the art of the Chinese Caribbean diaspora from the early 20th century to the present day. The presentation at CAAM traces the history of Chinese Caribbean art from the 1930s through the period of the region’s independence movements, showcasing the contributions of artists little known outside their own countries, such as Sybil Atteck (Trinidad and Tobago) and Manuel Chong Neto (Panama), and providing a new context for understanding the better-known work of Wifredo Lam (Cuba). At CAM, the exhibition focuses on the work of contemporary artists such as Albert Chong and Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, as well as artists of the ongoing Chinese Caribbean diaspora. Publication: The exhibition is accompanied by a catalog that will be the first publication devoted to Chinese Caribbean art history and visual culture. -

Theory of the Beautiful Game: the Unification of European Football

Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54, No. 3, July 2007 r 2007 The Author Journal compilation r 2007 Scottish Economic Society. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main St, Malden, MA, 02148, USA THEORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL GAME: THE UNIFICATION OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL John Vroomann Abstract European football is in a spiral of intra-league and inter-league polarization of talent and wealth. The invariance proposition is revisited with adaptations for win- maximizing sportsman owners facing an uncertain Champions League prize. Sportsman and champion effects have driven European football clubs to the edge of insolvency and polarized competition throughout Europe. Revenue revolutions and financial crises of the Big Five leagues are examined and estimates of competitive balance are compared. The European Super League completes the open-market solution after Bosman. A 30-team Super League is proposed based on the National Football League. In football everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team. FSartre I Introduction The beauty of the world’s game of football lies in the dynamic balance of symbiotic competition. Since the English Premier League (EPL) broke away from the Football League in 1992, the EPL has effectively lost its competitive balance. The rebellion of the EPL coincided with a deeper media revolution as digital and pay-per-view technologies were delivered by satellite platform into the commercial television vacuum created by public television monopolies throughout Europe. EPL broadcast revenues have exploded 40-fold from h22 million in 1992 to h862 million in 2005 (33% CAGR). -

The Chinese in Hawaii: an Annotated Bibliography

The Chinese in Hawaii AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY by NANCY FOON YOUNG Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii Hawaii Series No. 4 THE CHINESE IN HAWAII HAWAII SERIES No. 4 Other publications in the HAWAII SERIES No. 1 The Japanese in Hawaii: 1868-1967 A Bibliography of the First Hundred Years by Mitsugu Matsuda [out of print] No. 2 The Koreans in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Arthur L. Gardner No. 3 Culture and Behavior in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Judith Rubano No. 5 The Japanese in Hawaii by Mitsugu Matsuda A Bibliography of Japanese Americans, revised by Dennis M. O g a w a with Jerry Y. Fujioka [forthcoming] T H E CHINESE IN HAWAII An Annotated Bibliography by N A N C Y F O O N Y O U N G supported by the HAWAII CHINESE HISTORY CENTER Social Science Research Institute • University of Hawaii • Honolulu • Hawaii Cover design by Bruce T. Erickson Kuan Yin Temple, 170 N. Vineyard Boulevard, Honolulu Distributed by: The University Press of Hawaii 535 Ward Avenue Honolulu, Hawaii 96814 International Standard Book Number: 0-8248-0265-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-620231 Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Copyright 1973 by the Social Science Research Institute All rights reserved. Published 1973 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi ABBREVIATIONS xii ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 1 GLOSSARY 135 INDEX 139 v FOREWORD Hawaiians of Chinese ancestry have made and are continuing to make a rich contribution to every aspect of life in the islands. -

FY 19 4Th Quarter & FYE Lender Ranking

LOS ANGELES DISTRICT OFFICE 7(a) and 504 Lender Ranking Report Fiscal Year 2019 - Q4 (10/1/18 - 9/30/19) 7(a) Loan Program 504 Loan Program 1 U.S. Bank, National Association 184 $23,757,600 67 Mega Bank 5 $1,672,000 1 CDC Small Business Finance Corporation* 94 $98,783,000 2 JPMorgan Chase Bank, National Association 174 $44,541,500 68 PCR Small Business Development*++ 5 $821,000 2 Business Finance Capital*++ 92 $109,382,000 3 Bank of Hope++ 167 $60,333,000 69 Poppy Bank 4 $8,690,000 3 California Statewide Certified Development* 84 $67,087,000 4 Wells Fargo Bank, National Association 155 $36,193,900 70 Wallis Bank 4 $7,542,000 4 Mortgage Capital Development Corporation 38 $39,865,000 5 First Home Bank 104 $22,494,000 71 BBVA USA 4 $5,926,300 5 Advantage Certified Development Corporation 15 $17,387,000 6 East West Bank++ 61 $33,406,500 72 Pacific Mercantile Bank 4 $4,927,000 6 Southland Economic Development Corporation 14 $14,297,000 7 Pacific City Bank++ 60 $50,311,500 73 Pacific Western Bank++ 4 $4,165,000 7 So Cal CDC++ 11 $22,780,000 8 CDC Small Business Finance Corporation* 55 $8,763,500 74 OneWest Bank, A Division of 4 $4,013,000 8 AMPAC Tri-State CDC, Inc. 10 $7,235,000 9 MUFG Union Bank, National Association 50 $75,482,600 75 IncredibleBank 4 $2,123,600 9 Coastal Business Finance++ 6 $3,666,000 10 Hanmi Bank++ 50 $30,864,000 76 Kinecta FCU++ 4 $862,000 10 Enterprise Funding Corporation 2 $2,980,000 11 Commonwealth Business Bank++ 47 $38,305,000 77 Montecito Bank & Trust++ 4 $503,900 11 San Fernando Valley Small Business Development++ 2 $1,046,000 12 Celtic Bank Corporation 44 $14,667,300 78 Meadows Bank 3 $5,091,000 12 Superior California Economic Development 1 $2,111,000 13 Independence Bank 40 $5,725,000 79 Banner Bank 3 $2,175,000 13 Capital Access Group, Inc. -

Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago During the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 Samuel C. King Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Recommended Citation King, S. C.(2019). Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5418 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 by Samuel C. King Bachelor of Arts New York University, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Lauren Sklaroff, Major Professor Mark Smith, Committee Member David S. Shields, Committee Member Erica J. Peters, Committee Member Yulian Wu, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Abstract The central aim of this project is to describe and explicate the process by which the status of Chinese restaurants in the United States underwent a dramatic and complete reversal in American consumer culture between the 1890s and the 1930s. In pursuit of this aim, this research demonstrates the connection that historically existed between restaurants, race, immigration, and foreign affairs during the Chinese Exclusion era. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1959-03-03

,......, .. Report On SUI Presiclent VI,.II M. H~ rejlOrts on the pad y .... at SUI in a ..... rt Mriu .... Inni ... hi- 01 owon day on pa.. t. Serving The State University of Iowa and the People of Iowa City Five Cents a CIIPY Iowa city, towa. TUeSiGy. March 3. 1959 I Pro es aste oonwar ,• • • ata I'te Igna S n oar it Play Written Just To Provide Successful Belly Laughs: Author Sederholm Cape Firing By KAY KRESS associate prof sor or dramatic art. Staff Wrlt.r who is directing "Beyond Our Con· trol," ha added physical move· At Midnight " 'Beyond Our Control,' said its TINV TUBES WITH BIG RESPONSIBILITIES-Sil. or .pecl.lly sm.ller count,,. is enc.sed in le.d. to hllp scl.ntlsts to det.rmlne m nt lind slaging which add to how much shieldin, will be needed to pr.vl... .ar. P.... II. fer ~uthor, Fred Sederholm, "was writ the com dy effect. constructed lI.illlt' counters .board Pion", IV Is dr.matically ten simply to provide an audience All Four Stages Indinled by pencil .Iong side. Within the moon,sun probe th. the first m.n in sp.ce.-Ooily lowon Pheto, with several hours of belly Sed rholm aid he con Iders a Ignite Okay laughter." farce the mo t diCCicult to act be· cau e an actor can never "feel" II By JIM DAVIS "The play," he continued, "mere· comedy part. He must depend up· St.ff Write,. * * * ly presents a series oC, (! hope), on technique and concentrate on humorous incidents involving a 1300-Pound delivering lin . -

Minority Banks in New York City: Is the Community Reinvestment Act Relevant?

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 25 Issue 3 Volume 25, Spring 2011, Issue 3 Article 4 Minority Banks in New York City: Is the Community Reinvestment Act Relevant? Tarry Hum Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINORITY BANKS IN NEW YORK CITY: IS THE COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT RELEVANT? TARRY HUM, PH.D.* INTRODUCTION The United States has a long history of minority banks formed to meet the credit needs of populations excluded from mainstream financial institutions. Minority banks continue to be a prominent part of locally- based economic landscapes, but their record in individual asset building (e.g., homeownership) and community economic development is uneven at best. A recent example is Massachusetts-based OneUnited Bank, established by African Americans to underwrite the revitalization of urban poor neighborhoods. A long time advocate of minority banks, Congresswoman Maxine Waters is now a focus of a Congressional ethics committee inquiry on charges that she used her influence to arrange a meeting between OneUnited Bank representatives and US Treasury Department officials. While the media has covered extensively Congresswoman Waters' close personal ties to OneUnited Bank, what may be of greater consequence for African American communities is the nominal number of bank loans for community improvement.' In addition to an uneven role in community development, the demographic composition of minority banks has transformed in the past decades.