Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob's Pillow Rolls out 2020 Season

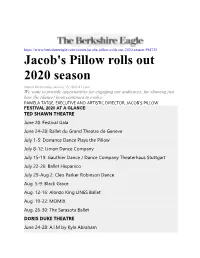

https://www.berkshireeagle.com/stories/jacobs-pillow-rolls-out-2020-season,594735 Jacob's Pillow rolls out 2020 season Posted Wednesday, January 15, 2020 4:15 pm We want to provide opportunities for engaging our audiences; for showing just how the (dance) form continues to evolve.” PAMELA TATGE, EXECUTIVE AND ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, JACOB'S PILLOW FESTIVAL 2020 AT A GLANCE TED SHAWN THEATRE June 20: Festival Gala June 24-28: Ballet du Grand Theatre de Geneve July 1-5: Dorrance Dance Plays the Pillow July 8-12: Limon Dance Company July 15-19: Gauthier Dance / Dance Company Theaterhaus Stuttgart July 22-26: Ballet Hispanico July 29-Aug 2: Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Aug. 5-9: Black Grace Aug. 12-16: Alonzo King LINES Ballet Aug. 19-22: MOMIX Aug. 26-30: The Sarasota Ballet DORIS DUKE THEATRE June 24-28: A.I.M by Kyle Abraham July 1-5: Dorrance Dance Plays the Pillow July 8-12: CONTRA-TIEMPO July 15-19: Duets from Quebec July 22-26: Dance Heginbotham July 29-Aug. 2: Malavika Sarukkai — Thari - The Loom Aug. 5-9: LAVA Companía de Danza Aug. 12-16: Brian Brooks Moving Company Aug. 19-23: Liz Lerman Aug. 26-30: Aszure Barton & Artists By The Berkshire Eagle BECKET — Four programs involving world premieres, three companies making Jacob's Pillow debuts, the return appearances of five companies, and work developed at Pillow Lab highlight Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival 2020, which begins June 24 and runs through Aug. 30 in the Ted Shawn and Doris Duke theaters. The season also will present new commissions, anniversary celebrations, Pillow-exclusive engagements, U.S. -

2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020

® 2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020 Report Summary The following is a report on the gender distribution of choreographers whose works were presented in the 2019-2020 seasons of the fifty largest ballet companies in the United States. Dance Data Project® separates metrics into subsections based on program, length of works (full-length, mixed bill), stage (main stage, non-main stage), company type (main company, second company), and premiere (non-premiere, world premiere). The final section of the report compares gender distributions from the 2018- 2019 Season Overview to the present findings. Sources, limitations, and company are detailed at the end of the report. Introduction The report contains three sections. Section I details the total distribution of male and female choreographic works for the 2019-2020 (or equivalent) season. It also discusses gender distribution within programs, defined as productions made up of full-length or mixed bill works, and within stage and company types. Section II examines the distribution of male and female-choreographed world premieres for the 2019-2020 season, as well as main stage and non-main stage world premieres. Section III compares the present findings to findings from DDP’s 2018-2019 Season Overview. © DDP 2019 Dance DATA 2019 - 2020 Season Overview Project] Primary Findings 2018-2019 2019-2020 Male Female n/a Male Female Both Programs 70% 4% 26% 62% 8% 30% All Works 81% 17% 2% 72% 26% 2% Full-Length Works 88% 8% 4% 83% 12% 5% Mixed Bill Works 79% 19% 2% 69% 30% 1% World Premieres 65% 34% 1% 55% 44% 1% Please note: This figure appears inSection III of the report. -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers: a Critical Look at the Leading Cause of Non-Traumatic Dance Injuries

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2018 The psychosocial effects of compensated turnout on dancers: a critical look at the leading cause of non-traumatic dance injuries Rachel Smith University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Rachel, "The psychosocial effects of compensated turnout on dancers: a critical look at the leading cause of non-traumatic dance injuries" (2018). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers 1 The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers: A Critical Look at the Leading Cause of Non-Traumatic Dance Injuries Rachel Smith Departmental Honors Thesis University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Department of Health and Human Performance Examination Date: March 22, 2018 ________________________________ ______________________________ Shewanee Howard-Baptiste Burch Oglesby Associate Professor of Exercise Science Associate Professor of Exercise Science Thesis Director Department Examiner ________________________________ Liz Hathaway Assistant Professor of Exercise -

Margaret Barbieri Conservatory Summer Intensive

The Sarasota Ballet – Margaret Barbieri Conservatory Summer Intensive 27 June - 30 July 2016 Strengthen Technique - Learn Legendary Repertoire - Develop Artistry Faculty to include: - Iain Webb, Director of The Sarasota Ballet - Margaret Barbieri, Assistant Director of The Sarasota Ballet - Nancie Woods, Principal of The Conservatory - Renowned Guest Faculty to be announced at a later date The Pre-Professional Summer Intensive is a 5-week program (27 June - 30 July 2016) for ages 12 - 18. Younger students should have at least 3 years of serious ballet training and ladies must be en pointe. Information about tuition and housing will be available soon. Audition dates and locations are listed below. The Junior Summer Intensive is a 3-week program (11 July - 30 July 2016) for ages 9 - 11. Participation in all 3 weeks is mandatory and students should have at least 2 years of serious ballet training. There is no housing available for Junior Summer Intensive students. Auditions for the Junior Summer Intensive will be held in Sarasota only (see below); out of town students can send a video audition, with letter stating that their parent/guardian will be acccompanying them for the 3-week summer session. Audition Schedule There is a $25 audition fee. Please bring a headshot and 1st arabesque photo. Sarasota - 3 January 2016 Junior Summer Intensive Registration: 1:30 PM - 2:00 PM; Audition 2:00 PM - 3:15 PM Pre-Professional Summer Intensive Registration: 3:30 PM - 4:00 PM; Audition 4:00 PM - 5:30 PM The Sarasota Ballet - Margaret Barbieri Conservatory, -

There's Even More to Explore!

Background artwork: SPECIAL COLLECTIONS UCHICAGO LIBRARY Kaplan and Fridkin, Agit No. 2 MUSIC THEATER ART MUSIC THEATER LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC MUSIC MUSIC / FILM LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC University of Chicago Presents University Theater/Theater and Performance Studies The University of Chicago Library Symphony Center Presents Goodman Theatre University of Chicago Presents Roosevelt University Rockefeller Chapel University of Chicago Presents TOKYO STRING QUARTET THEATER 24 PLAY SERIES: GULAG ART Orchestra Series CHEKHOv’S THE SEAGULL LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN PAciFicA QUARTET: 19TH ANNUAL SILENT FiLM LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN BY MARiiNskY ORCHESTRA FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 A CLOUD WITH TROUSERS THROUGH DECEMBER 2010 OCTOber 16 – NOVEMBER 14, 2010 BY PACIFICA QUARTET SHOSTAKOVICH CYCLE WITH ORGAN AccomPANimENT: MAsumi RosTAD, VioLA, AND (FORMERLY KIROV ORCHESTRA) Mandel Hall, 1131 East 57th Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2010, 8 PM The Joseph Regenstein Library, 170 North Dearborn Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 16, 2 PM SUNDAY OCTOBER 17, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM AELITA: QUEEN OF MARS AMY BRIGGS, PIANO th nd chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 First Floor Theater, Reynolds Club, 1100 East 57 Street, 2 Floor Reading Room Valery Gergiev, conductor Goodmantheatre.org, 312.443.3800 Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street SUNDAY OCTOBER 31, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM Jay Warren, organ SATURDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2 PM 5706 South University Avenue Lib.uchicago.edu Denis Matsuev, piano Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2010, 8 PM Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street Mozart: Quartet in C Major, K. 575 As imperialist Russia was falling apart, playwright Anton SUNDAY JANUARY 30, 2011, 2 AND 7 PM ut.uchicago.edu TUESDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2010, 8 PM Rockefeller Chapel, 5850 South Woodlawn Avenue Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 Lera Auerbach: Quartet No. -

Nicolle Greenhood Major Paper FINAL.Pdf (4.901Mb)

DIVERSITY EN POINTE: MINIMIZING DISCRIMINATORY HIRING PRACTICES TO INCREASE BALLET’S CULTURAL RELEVANCE IN AMERICA Nicolle Mitchell Greenhood Major paper submitted to the faculty of Goucher College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arts Administration 2016 Abstract Title of Thesis: DIVERSITY EN POINTE: MINIMIZING DISCRIMINATORY HIRING PRACTICES TO INCREASE BALLET’S CULTURAL RELEVANCE IN AMERICA Degree Candidate: Nicolle Mitchell Greenhood Degree and Year: Master of Arts in Arts Administration, 2016 Major Paper Directed by: Michael Crowley, M.A. Welsh Center for Graduate and Professional Studies Goucher College Ballet was established as a performing art form in fifteenth century French and Italian courts. Current American ballet stems from the vision of choreographer George Balanchine, who set ballet standards through his educational institution, School of American Ballet, and dance company, New York City Ballet. These organizations are currently the largest-budget performing company and training facility in the United States, and, along with other major US ballet companies, have adopted Balanchine’s preference for ultra thin, light skinned, young, heteronormative dancers. Due to their financial stability and power, these dance companies set the standard for ballet in America, making it difficult for dancers who do not fit these narrow characteristics to succeed and thrive in the field. The ballet field must adapt to an increasingly diverse society while upholding artistic integrity to the art form’s values. Those who live in America make up a heterogeneous community with a blend of worldwide cultures, but ballet has been slow to focus on diversity in company rosters. -

The Social-Psychological Outcomes of Dance Practice: a Review

DOI:10.2478/v10237-011-0067-ySport Science Review, vol. XX, No. 5-6, December 2011 The Social-Psychological Outcomes of Dance Practice: A Review Alexandros MALKOGEORGOS* • Eleni ZAGGELIDOU* Evagelos MANOLOPOULOS* • George ZAGGELIDIS* ance involvement among the youth has been described in many Dterms. Studies regarding the effects of dance practice on youth show different images. Most refer that dance enhanced personal and social opportunities, increased levels of socialization and characteristic behavior among its participants. Socialization in dance differs according to dance forms, and a person might become socialized into them not only in childhood and adolescence but also well into adulthood and mature age. The aim of the present review is to provide an overview of the major findings of studies concerning the social-psychological outcomes of dance practice. This review revealed that a considerable amount of researches has been conducted over the years, revealed positive social- psychological outcomes of dance practice, in a general population, as well as specifically for adults or for adolescents. According to dance form the typical personality profile of dancers, danc- ers being introverted, relatively high on emotionality, strongly achievement motivated and exhibiting less favorable self attitudes. It is proposed that a better understanding of the true nature of the social-psychological outcomes of dance practice can be provided if specific influential factors are taken into account in future research (i.e., participants’ characteristics, type of guidance, social context and structural qualities of the dance). Keywords: dance, youth, personality traits, socialization Introduction Dance can be performed at home or at a park, without any equipment, alone or in a group, is a choreographed routine of movements usually performed to music. -

Bruhn, Erik (1928-1986) Erik Bruhn (Second from Left) Visiting Backstage at by John Mcfarland the New York City Ballet

Bruhn, Erik (1928-1986) Erik Bruhn (second from left) visiting backstage at by John McFarland the New York City Ballet. The group included (left Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. to right) Diana Adams, Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Bruhn, Violette Verdy, Sonia Arova, and Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Rudolph Nureyev. Erik Bruhn was the premier male dancer of the 1950s and epitomized the ethereally handsome prince and cavalier on the international ballet stage of the decade. Combining flawless technique with an understanding of modern conflicted psychology, he set the standard by which the next generation of dancers, including Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Peter Schaufuss, and Peter Martins, measured their success. Born on October 3, 1928 in Copenhagen, Bruhn was the fourth child of Ellen Evers Bruhn, the owner of a successful hair salon. After the departure of his father when Erik was five years old, he was the sole male in a household with six women, five of them his seniors. An introspective child who was his mother's favorite, Erik was enrolled in dance classes at the age of six in part to counter signs of social withdrawal. He took to dance like a duck to water; three years later he auditioned for the Royal Danish Ballet School where he studied from 1937 to 1947. With his classic Nordic good looks, agility, and musicality, Bruhn seemed made for the August Bournonville technique taught at the school. He worked obsessively to master the technique's purity of line, lightness of jump, and clean footwork. Although Bruhn performed the works of the Royal Danish Ballet to perfection without any apparent effort, he yearned to reach beyond mere technique. -

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 Pm

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 pm Photo:Photo: Benoit © Paul Lemay Kolnik 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PETER MARTINS ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATOR JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH THE DANCERS PRINCIPALS ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING CHASE FINLAY ABI STAFFORD SOLOIST UNITY PHELAN CORPS DE BALLET MARIKA ANDERSON JACQUELINE BOLOGNA HARRISON COLL CHRISTOPHER GRANT SPARTAK HOXHA RACHEL HUTSELL BAILY JONES ALEC KNIGHT OLIVIA MacKINNON MIRIAM MILLER ANDREW SCORDATO PETER WALKER THE MUSICIANS ARTURO DELMONI, VIOLIN ELAINE CHELTON, PIANO ALAN MOVERMAN, PIANO BALLET MASTERS JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH CRAIG HALL LISA JACKSON REBECCA KROHN CHRISTINE REDPATH KATHLEEN TRACEY TOURING STAFF FOR NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES COMPANY MANAGER STAGE MANAGER GREGORY RUSSELL NICOLE MITCHELL LIGHTING DESIGNER WARDROBE MISTRESS PENNY JACOBUS MARLENE OLSON HAMM WARDROBE MASTER MASTER CARPENTER JOHN RADWICK NORMAN KIRTLAND III 3 Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop Photo © Paul Kolnik for all of your instrument, EVENT SPONSORS accessory, and service needs! RICHARD AND MARY JO STANLEY ELLIE AND PETER DENSEN ALLYN L. MARK IOWA HOUSE HOTEL SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Season Sponsor! Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop for all of your instrument, accessory, and service needs! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! THE PROGRAM IN THE NIGHT Music by FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Choreography by JEROME ROBBINS Costumes by ANTHONY DOWELL Lighting by JENNIFER TIPTON OLIVIA MacKINNON UNITY PHELAN ABI STAFFORD AND AND AND ALEC KNIGHT CHASE FINLAY ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING Piano: ELAINE CHELTON This production was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. -

Miami City Ballet 37

Miami City Ballet 37 MIAMI CITY BALLET Charleston Gaillard Center May 26, 2:00pm and 8:00pm; Martha and John M. Rivers May 27, 2:00pm Performance Hall Artistic Director Lourdes Lopez Conductor Gary Sheldon Piano Ciro Fodere and Francisco Rennó Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra 2 hours | Performed with two intermissions Walpurgisnacht Ballet (1980) Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Music Charles Gounod Staging Ben Huys Costume Design Karinska Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Katia Carranza, Renato Penteado, Nathalia Arja Emily Bromberg, Ashley Knox Maya Collins, Samantha Hope Galler, Jordan-Elizabeth Long, Nicole Stalker Alaina Andersen, Julia Cinquemani, Mayumi Enokibara, Ellen Grocki, Petra Love, Suzette Logue, Grace Mullins, Lexie Overholt, Leanna Rinaldi, Helen Ruiz, Alyssa Schroeder, Christie Sciturro, Raechel Sparreo, Christina Spigner, Ella Titus, Ao Wang Pause Carousel Pas de Deux (1994) Choreography Sir Kenneth MacMillan Music Richard Rodgers, Arranged and Orchestrated by Martin Yates Staging Stacy Caddell Costume Design Bob Crowley Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Jennifer Lauren, Chase Swatosh Intermission Program continues on next page 38 Miami City Ballet Concerto DSCH (2008) Choreography Alexei Ratmansky Music Dmitri Shostakovich Staging Tatiana and Alexei Ratmansky Costume Design Holly Hynes Lighting Design Mark Stanley Dancers Simone Messmer, Nathalia Arja, Renan Cerdeiro, Chase Swatosh, Kleber Rebello Emily Bromberg and Didier Bramaz Lauren Fadeley and Shimon Ito Ashley Knox and Ariel Rose Samantha -

Inflectional Marking on Terminological Borrowings in Classical Ballet

Beyond Philology No. 15/2, 2018 ISSN 1732-1220, eISSN 2451-1498 Beyond dance: Inflectional marking on terminological borrowings in classical ballet FRANČIŠKA LIPOVŠEK Received 3.11.2017, received in revised form 1.02.2018, accepted 28.02.2018. Abstract Most classical ballet terminology comes from French. English and Slovene adopt the designations for ballet movements without any word-formational or orthographic modifications. This paper presents a study into the behaviour of such unmodified borrowings in written texts from the point of view of inflectional marking. The research involved two questions: the choice between the donor-language and recipient-language marking and the placement of the inflection in syntactically complex terms. The main point of interest was the marking of number. The research shows that only Slovene employs native inflections on the borrowed terms while English adopts the ready-made French plurals. The behaviour of the terms in Slovene texts was further examined from the points of view of gender/case marking and declension class assignment. The usual placement of the inflection is on the postmodifier closest to the headword. Key words classical ballet, terminology, borrowing, inflectional marking, English, Slovene 42 Beyond Philology 15/2 Poza tańcem: Fleksyjne znakowanie zapożyczeń w terminologii klasycznego baletu Abstrakt Większość klasycznej terminologii baletowej pochodzi z języka fran- cuskiego. Angielski i słoweński przyswajają nazwy baletowe bez żad- nych modyfikacji słowotwórczych lub ortograficznych. W artykule przedstawiono badanie takich niezmodyfikowanych zapożyczeń w tekstach pisanych z punktu widzenia fleksyjnego znakowania. Ba- dania obejmowały dwie kwestie: wybór pomiędzy oznaczeniem języka źródłowego a języka odbiorcy oraz fleksja w terminach składniowo złożonych.