Urban Waterways Newsletter Issue 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments Received

PARKS & OPEN SPACE ELEMENT (DRAFT RELEASE) LIST OF COMMENTS RECEIVED Notes on List of Comments: ⁃ This document lists all comments received on the Draft 2018 Parks & Open Space Element update during the public comment period. ⁃ Comments are listed in the following order o Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions o Comments from Local & Regional Agencies o Comments from Interest Groups o Comments from Interested Individuals Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE National Capital Region 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. IN REPLY REFER TO: Washington, D.C. 20242 May 14, 2018 Ms. Surina Singh National Capital Planning Commission 401 9th Street, NW, Suite 500N Washington, DC 20004 RE: Comprehensive Plan - Parks and Open Space Element Comments Dear Ms. Singh: Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments on the draft update of the Parks and Open Space Element of the Comprehensive Plan for the National Capital: Federal Elements. The National Park Service (NPS) understands that the Element establishes policies to protect and enhance the many federal parks and open spaces within the National Capital Region and that the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) uses these policies to guide agency actions, including review of projects and preparation of long-range plans. Preservation and management of parks and open space are key to the NPS mission. The National Capital Region of the NPS consists of 40 park units and encompasses approximately 63,000 acres within the District of Columbia (DC), Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia. Our region includes a wide variety of park spaces that range from urban sites, such as the National Mall with all its monuments and Rock Creek Park to vast natural sites like Prince William Forest Park as well as a number of cultural sites like Antietam National Battlefield and Manassas National Battlefield Park. -

Junior Ranger Program, National Capital Parks-East

National Park Service Junior Ranger Program U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. National Capital Parks-East Maryland Table of Contents 2. Letter from the Superintendent 3. National Park Service Introduction 4. National Capital Parks-East Introduction 5. How to Become an Official Junior Ranger 6. Map of National Capital Parks-East 7. Activity 1: National Capital Parks-East: Which is Where? 8. Activity 2: Anacostia Park: Be a Visitor Guide 9. Activity 3: Anacostia Park: Food Chain Mix-Up 10. Activity 4: Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: Create a Timeline 11. Activity 5: Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: Cinquain Poems 12. Activity 6: Fort Dupont Park: Be an Environmentalist 13. Activity 7: Fort Dupont Park: Be a Biologist 14. Activity 8: Fort Washington Park: Be an Architect 15. Activity 9: Fort Washington Park: The Battle of Fort Washington 16. Activity 10: Federick Douglass National Historic Site: Create Your Dream House 17. Activity 11: Frederick Douglass National Historic Site: Scavenger Hunt Bingo 18. Activity 12: Greenbelt Park: Recycle or Throw Away? 19. Activity 13: Greenbelt Park: Be a Detective 20. Activity 14: Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens: What am I? 21. Activity 15: Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens: Be a Consultant 22. Activity 16: Langston Golf Course: Writing History 23. Activity 17: Langston Golf Course: Be a Scientist 24. Activity 18: Oxon Hill Farm: Be a Historian 25. Activity 19: Oxon Hill Farm: Where Does Your Food Come From? 26. Activity 20: Piscataway Park: What’s Wrong With This Picture? 27. Activity 21: Piscataway Park: Be an Explorer 28. -

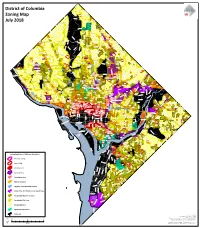

Pending Zoning Ac Ve PUD Pending PUD Campus Plans Downtown

East Beach Dr NW Beach North Parkway Portal District of Columbia Eastern Ave NW R-1-A Portal Dr NW Parkside Dr NW Kalmia Rd NW 97-16D Zoning Map 32nd St NW RA-1 12th St NW Wise Rd NW MU-4 R-1-B R-2 16th St NW R-2 76-3 Geranium St NW July 2018 Pinehurst Parkway Beech St NW Piney Branch Portal Aberfoyle Pl NW WR-1 RA-1 Alaska Ave NW WR-2 Takoma MU-4"M Worthington St NW WR-3 Dahlia St NW MU-4 WR-4 NC-2 R-1-A WR-6 RA-1 Utah Ave NW 31st Pl NW WR-6 MU-4 WR-5 RA-1 WR-7 Sherrill Dr NW WR-8 WR-3 MU-4 WR-5 Aspen St NW Nevada Ave NW Stephenson Pl NW Oregon Ave NW 30th St NW RA-2 4th St NW R-2 Van Buren St NW 2nd St NW Harlan Pl NW Pl Harlan R-1-B Broad Branch Rd NW Luzon Ave NW R-2 Pa�erson St NW Tewkesbury Pl NW 26th St NW R-1-B Chevy Tuckerman St NE Chase NW Pl 2nd Circle MU-3 Sheridan St NW Blair Rd NW Beach Dr NW R-3 MU-3 MU-3 MU-4 R-1-B Mckinley St NW Fort Circle Park 14th St NW Morrison St NW PDR-1 1st Pl NE 05-30 R-2 R-2 RA-1 MU-4 RA-4 Missouri Ave NW Peabody St NW Francis G. RA-1 04-06 Lega�on St NW Newlands Park RA-2 (Little Forest) Eastern Ave NE Morrow Dr NW RA-3 MU-7 Oglethorpe St NE Military Rd NW 2nd Pl NW 96-13 27th St NW Kanawha St NW Fort Slocum Friendship Heights Nicholson St NW Park MU-7 MU-5A R-2 R-2 "M Fort R-1-A NW St 9th Reno Rd NW Glover Rd NW Circle 85-20 R-3 Fort MU-4 R-2 NW St 29th Park MU-5A Circle Madison St NW MU-4 Park R-3 R-1-A RF-1 PDR-1 RA-2 R-8 RA-2 06-31A Fort Circle Park Linnean Ave NW R-16 MU-4 Rock Creek Longfellow St NW Kennedy St NE R-1-B RA-1 MU-4 RA-4 Ridge Rd NW Park & Piney MU-4 R-3 MU-4 Kennedy St NW -

Known Wetlands Within the District of Columbia

Government of District 36 of Columbia District Department of the of the Environment Water Quality Division 1200 First St. NE, 5th Floor Washington, DC 20002 (202) 535-2190 46 47 48 40 38 4 3 37 11 5 41 6 1 10 8 39 12 7 14 17 2 15 13 9 16 42 44 18 19 45 43 20 21 22 23 26 24 27 Key to Features 29 25 30 31 32 28 Wetlands Waterbodies 33 34 Known Wetlands within the Note: 1. Delineation based on 1996 field reconnaissance 2. Wetland boundaries shown are intended for District of Columbia planning purposes and do not reflect jurisdiction 35 under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act. Identified by Number 3. Wetlands shown do not include the Potomac and Anacostia open water areas. Source: District of Columbia Wetland Conservation Plan, 1997 3036Miles Projection: UTM spheroid Clarke 1866 Zone: 18 Date: January, 2001 The following is a list of the KNOWN wetlands in the District of Columbia based on the District of Columbia Wetland Conservation Plan (1997). There are many wetlands within the city that are not listed here including the open water areas of the Potomac and Anacostia. Wetland Location ADC Grid Longitude Latitude No. 1 Beaverdam Creek at Kenilworth Courts 11-D11 76-56'-38"/56'06" 38-54'-56"/54'-39" 2 Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens 11-B,C12 76-57'-00"/56'-28" 38-54'-54"/54'-30" 3 Fort Lincoln New Town between Rt. 50 and 11-C9 76-56'-39" 38-55'-02" Fort Lincoln cemetery 4 Fort Lincoln between Rt. -

Anacostia Great Outdoors Factsheet (PDF)

Anacostia’s Great Outdoors: Fact Sheet Connecting People and the Anacostia removal of more than 20 acres of landfill. Additionally, the In partnership with the federal government, the District of project included: planting 85,000 wetland plants, reforesting Columbia and State of Maryland are working to restore the 14 acres of land, creating 20 acres of tidal wetland, and Anacostia River and provide safe and convenient means for preserving four acres of habitat along the Anacostia River. people to access the Anacostia River and enjoy the outdoors. Connecting DC and Maryland The Anacostia Riverwalk Trails will link together hundreds of Maryland, the District, and the U.S. Department of miles of regional trails; including the Fort Circle Trail (DC), the Transportation are working to design and build the critical Bladensburg Trail (MD), the Rock Creek Trail (DC and MD), the Kenilworth Gardens Section, which will connect the Maryland Mount Vernon Trail (VA) and the C&O Canal Trail (DC and and District Anacostia Riverwalk Trail Networks. Design is 65 MD). These connections will also provide access to the East percent complete and construction will begin in 2012. Coast Greenway, a network of trails linking Maine to Florida. Maryland is providing an additional $1 million from the Cycle Maryland Bikeways Program to build this critical connection. Anacostia Riverwalk Trail - DC With 12 miles already in place and a total of 20 miles planned, New Cycle Maryland Bicycle Funding Programs the Anacostia Riverwalk trail in Washington, DC will connect Today, Governor O’Malley announced two new bicycle sixteen waterfront neighborhoods to Anacostia Park and the funding programs to move forward his Cycle Maryland Anacostia River. -

Anacostia Park Temporary Art Installation

Delegated Action of the Executive Director PROJECT NCPC FILE NUMBER Temporary Public Art Installation in 7808 Anacostia Park, Section D Located along the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail, NCPC MAP FILE NUMBER and Anacostia Drive, SE 8.10(38.00)44390 Washington, DC ACTION TAKEN Approve as requested SUBMITTED BY United States Department of the Interior REVIEW AUTHORITY National Park Service Approval Per 40 U.S.C. § 8722(b)(1) and (d) The National Park Service, National Capital Parks – East (NACE), in collaboration with the 11th Street Bridge Park (a project of Building Bridges Across the River at THEARC) and the Ward 8 Arts and Culture Council, has submitted preliminary and final site development plans for a temporary art installation located in Anacostia Park, Section D along the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail and Anacostia Drive in southeast, Washington, DC. The project will entail the installation of four pieces of art located between the John Philip Sousa/Pennsylvania Avenue, SE Bridge and the 11th Street Bridge, with one art work located to the southwest of the 11th Street Bridge. The area is an active recreational zone, and the artwork will be a focal point for the visitors who use the trail. The art sculptures are intended to be in use for three years following installation. After this period, the art installation will be removed. The purpose of the project is to celebrate the Anacostia River, its history, ecology and communities that live alongside its banks. Designed by local high school students and artists, the art work includes four themes: flora and fauna of the Anacostia River; early Native American presence; the Navy Yard; and the African American experience. -

Washington's Waterfront Study

WASHINGTON’S WATERFRONTS Phase 1 December 1999 The Georgetown Waterfront Anacostia Park’s West Bank Potomac River r Rive Anacostia The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Washington Navy Yard and Southeast Waterfront National Capital Planning Commission Southwest Waterfront Anacostia Park’s East Bank 801 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Suite 301 Bolling Anacostia Waterfront Washington, D.C. 20576 tel 202 482-7200 fax 202 482-7272 An Analysis of Issues and Opportunities Along the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers www.ncpc.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION.............................................2 A. Overview B. Study Origin C. Study Process D. Study Goals E. Study Area II. THE WATERFRONT.......................................4 A. Regional Context B. Area Description C. Existing Conditions D. Land Use E. Transportation F. Urban Image III. WATERFRONT ISSUES..............................12 A. Identification of Concerns B. Planning Issues C. Opportunities D. Development Guidelines E. Implementation Tools IV. THE WATERFRONT PLAN.........................16 Recommended Outline V. CONCLUSION.............................................17 VI. APPENDIX..................................................18 1 7. Develop a waterfront redevelopment zone in areas 2. Enhance public access to the river. I. INTRODUCTION where major new development is proposed and ensure that existing maritime uses are protected. 3. Protect the natural setting of the valued open spaces A. Overview along the rivers. 8. Establish public transportation where needed and This document was developed to study the waterfront as a resource encourage the development of adequate parking in 4. Identify opportunities for attracting additional river- that belongs to all of the people of the United States and to the resi- redeveloped areas. related activities that can aid in revitalizing the District's dents of the District of Columbia. -

WASHINGTON, D.C. Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage

WASHINGTON, D.C. Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage . LWCF Funded Places in Washington, D.C. LWCF Success in Washington, D.C. The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has provided funding to help protect some of Washington, D.C.’s most special places and ensure Federal Program recreational access for hiking, cycling, fishing and other outdoor Ford’s Theatre NHS activities. Washington, D.C. has received approximately $18 million in FDR Memorial LWCF funding over the past five decades, protecting places such as the National Capital Parks-East Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Mary McLeod Bethune NHS, and Mary McLeod Bethune NHS National Capital Parks-East. Federal Total $4,200,000 LWCF state assistance grants have further supported hundreds of projects across Washington, D.C.’s local parks including Mitchell Park State Program Playground, Randall Recreation Center, and the East Potomac Park Total State Grants $13,800,000 Swimming Pool. Total $18,000,000 Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens Visitors and residents of Washington, D.C. experience the natural habitat of the area at the beautifully preserved Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens. This wetland helps mitigate pollution, reduces flood damage, and alleviates risks from climate change. As part of the National Capital Parks East, this park which has hiking trails, boardwalks, and comprehensive environmental education resources, has received a portion of the $2.5 million of LWCF awarded to the District’s network of parks. In addition to many events over the year, members of the D.C. Garden Club plant thousands of lotus each spring, a one-of-a-kind spectacle that draws visitors from across town and around the world. -

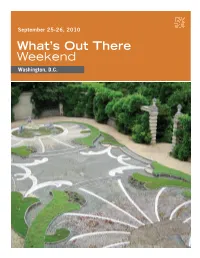

What's out There Weekend

September 25-26, 2010 What’s Out There Weekend Washington, D.C. September 2010 Dear TCLF Visitor, Welcome to What’s Out There Weekend! The materials in this booklet will tell you all you need to know about engaging in this exciting event, the first in a series which we hope to continue in other cities throughout the United States. On September 25-26 in Washington, D.C., TCLF will host What’s Out There Weekend, providing residents and visitors an opportunity to discover and explore more than two dozen free, publicly accessible sites in the nation’s capital. During the two days of What’s Out There Weekend, TCLF will offer free tours by expert guides. Washington, D.C. has one of the nation’s great concentrations of designed landscapes – parks, gardens and public spaces – laid out by landscape architects or designers. It’s an unrivaled legacy that stretches back more than 200 years and includes Pierre L’Enfant’s plan for the city, Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr.’s design for the U.S. Capitol grounds and Dan Kiley’s plaza at the National Gallery of Art. Throughout the weekend, expert guides will lead tours that shed new light on some of the city’s most iconic landscapes and introduce you to places you may not have known before. TCLF’s goal is to make visible these sites and their stories just like the capital city’s great buildings, monuments and memorials. The What’s Out There Weekend initiative dovetails with the web-based What’s Out There (WOT), the first searchable database of the nation’s historic designed landscapes. -

Civilian Conservation Corps Activities in The

CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS ACTIVITIES IN THE HABS DC-858 NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION OF THE NATIONAL PARK DC-858 SERVICE National Capital Parks-Central Washington District of Columbia WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS ACTIVITIES IN THE NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HABS No. DC-858 Location: Washington, District of Columbia; Arlington County, Prince William County, and Alexandria, Virginia; Prince George's County and Frederick County, Maryland. Present Owner: National Capital Region, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior Present Occupant: Various park units in the National Capital Region Present Use: Park and recreational facilities Significance: The Civilian Conservation Corps activities in the National Capital Region of the National Park Service illustrate the important role of this program in employing out-of-work youth to create a national recreation infrastructure during the 1930s. The National Capital Region work represents a mix of rural and urban projects indicative of CCC initiatives in metropolitan areas. While not as well-known as the rustic architecture built by the CCC for national parks in wilderness areas, the Washington-area CCC camps participated in many types of construction and tasks including parkways, picnic groves, erosion control, playgrounds, athletic fields, historical restorations, and Recreational Demonstration Area camping facilities. Many of these projects formed the basis for later expansion of recreational amenities in the National Capital Region. Historians: Lisa Pfueller Davidson (overview narrative), James A. Jacobs (inventory methodology) Project Information: This overview history and a detailed site inventory were undertaken by the Historic American Buildings Survey program of the National Park Service (NPS), Paul Dolinsky, Chief (HABS) and John A. -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Marconi

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2007 Marconi Memorial, US Reservation 309 A Rock Creek Park - DC Street Plan Reservations Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Marconi Memorial, US Reservation 309 A Rock Creek Park - DC Street Plan Reservations Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. In addition, for landscapes that are not currently listed on the National Register and/or do not have adequate documentation, concurrence is required from the State Historic Preservation Officer or the Keeper of the National Register. -

National Capital Parks and Is Not Field for the Nature Student

NATIONAL CAPITAL t PARKS UNITED STATES Page National DEPARTMENT OF THE Rock Creek Park .8 INTERIOR Anacostia and Fort Dupont OPEN Capital Parks J. A. Krug, Secretary Parks 8 ALL YEAR WASHINGTON Meridian Hill Park 9 19 49 Prince William Forest Park THE MALL and Catoctin Park . 9 FROM THE CAPITOL NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Newton B. Drury, Director Parkway 9 C 0?iT EDIT S Mount Vernon Memorial HE PARKS of the National ated on the remaining reservations Highway 9 Capital embrace 750 reser from time to time, the most impor The Washington Monument vations totaling approxi tant being Lafayette, Judiciary, (Cover) T Roaches Run Waterfowl mately 42,000 acres of land in the Franklin, and Garfield Parks. Sanctuary 10 District of Columbia and its environs, The original areas donated for Page including the Chesapeake & Ohio streets were exceedingly wide and Early History 3 Kenilworth Aquatic Canal, which extends from Washing permitted the establishment of parks, ton to Cumberland, Md. The park circles, and triangles at intersections. Gardens 10 The Mall 4 system was established under author From such areas came Lincoln, Smaller Parks 10 ization of act of July 16, 1790, and Stanton, Farragut, McPherson, Mar The Washington has remained under continuous Fed ion, and Mount Vernon Parks; Famous Circles 11 eral control for a period of 159 years. Washington, Dupont, Scott, Thomas, Monument 4 On August 10, 1933, it became a unit and Logan Circles; and many small The White House ... 5 Additional Units of the of the National Park Service. reservations. As the Capital grew in size and The President's Park 5 System 12 EARLY HISTORY importance, additional park areas were acquired including East and The Lincoln Memorial 6 Historic Structures .