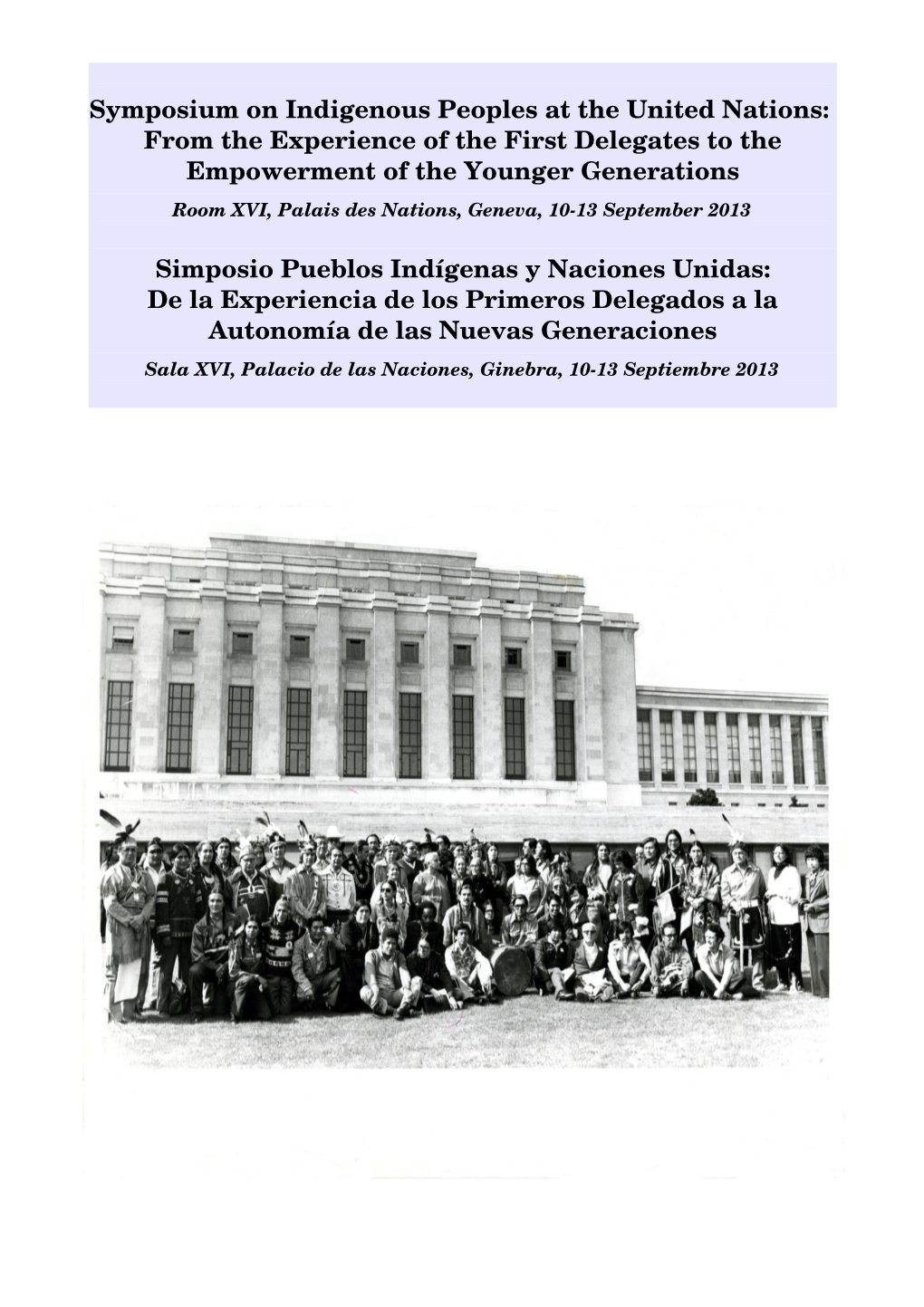

Simposio Pueblos Indígenas Y Naciones Unidas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natives Enter Mainstream Politics

Whoa! I said whoaaaaa... Dennis Samson of Hobbema twisted this critter sunshine and payoffs for the winners. down in 14 seconds flat, fast enough to grab fourth rounds are acknowledged as one of the place money. Samson and a whole mess of fin . -t in roe; ountry and the Indian rodeo circuit cowboys converged at Hobbema's Panee rodeo a ayytibr Afro -titors together for renewed grounds for the annual Spring Bust Out Rodeo. fr - ndshUonN I :t.'Ai .mpetition. The event got off wet and windy but wound up with 1Weft6 Te sty, Windspeaker Jat 2 7 rü Natives enter mainstream politics TERRY LUSTY, WiMSpeaker BY TERRY LUSTY Windspeaker Correspondent What a week it's been for Murial Stanley -Venne, Mike Cardinal and Willie Littlechild. The politicians have been nominated to represent their respective parties in separate elections. The first occurred June 11 when Muriel Stanley - Venne won the New Financial records Democratic nomination for the Yellowhead federal rid- ing currently held by PC kept Joe Clarke. from public In winning the NDP nom- ination for Yellowhead, BY DOROTHY SCHREIBER berships will be taken away Stanley -Venne will be out and LESLEY CROSSINGHAM "until we get rid of all the to unseat federal member troublemakers...there's no of Parliament Joe Clarke. law stating we have to put President of the Metis Stanley -Venne says she up with troublemakers." does not feel intimidated by Association Larry Des - Edson Local 44 president Clarke who is a meules has revoked mem- seasoned Sharon Johnstone and veteran when it comes to berships from individuals three of her members had requesting a look at the politics. -

Ermineskin Newsletter May 24, 2019 Neyâskweyâhk Acimowin Opiniyâwewipîsim Nîstanaw-Newosâp Akimaw Anohc ᓀᔮᐢᑫᐧᔮᐦᐠ ᐊᒋᒧᐊᐧᐣ ᐅᐱᓂᔮᐁᐧᐃᐧᐲᓯᒼ ᓃᐢᑕᓇᐤ-ᓀᐅᐧᓵᑊ ᐊᑭᒪᐤ ᐊᓄᐦᐨ

Neyâskweyâhk Acimowin Opiniyâwewipîsim Nîstanaw-Newosâp Akimaw Anohc Ermineskin Newsletter May 24, 2019 Neyâskweyâhk Acimowin Opiniyâwewipîsim Nîstanaw-Newosâp Akimaw Anohc ᓀᔮᐢᑫᐧᔮᐦᐠ ᐊᒋᒧᐊᐧᐣ ᐅᐱᓂᔮᐁᐧᐃᐧᐲᓯᒼ ᓃᐢᑕᓇᐤ-ᓀᐅᐧᓵᑊ ᐊᑭᒪᐤ ᐊᓄᐦᐨ Hide Tanning with Flora Northwest and Don Johnson ay 10, 2019 - M Flora North- west and Don John- son were teaching MESC students from the Maskwacis Out- reach School how to prepare hide at the Ermineskin Cree Lan- guage department. Flora was working with a scraper that has been handed down in her family for around 250 years (pictured bot- tom, second from left). She received it from her mother-in- law, Annie Cardinal, in the late 80s. It was passed down from older women to younger women, who typically “They fleshed it, we’re probably going to finish this to- kept it for 50 years. This is the first time she took it day,” said Flora. Don Johnson said that they already out to use it. Flora and Don were out with the stu- had the brains ready to process the hide afterward. dents for 3 days, and the third day they were all out The brains are traditionally used in the processing of scraping the fur off of the hide they had been working hide and Don is glad to reintroduce the youth of on. “We have 6-7 students, Marty Street provided the Maskwacis to traditional activities like hide-tanning. hide.” “I can show [them] how to make hide pouches,” said There will be further classes available to MESC students Don. “Passing it on to them, I’m 72 years old, this is who are participating in the land-based learning classes. -

Sponsorship Package.Indd

2017 NORTH AMERICAN INDIGENOUS GAMES SPONSORSHIP PACKAGE JULY 16 - 23, 2017 | TORONTO, ONTARIO WELCOME TO 2017 NAIG JULY 16-23, 2017 FUNDED BY SUPPORTED BY HOSTED BY NORTH AMERICAN INDIGENOUS GAMES 2017 1 One of the largest sporting and cultural gatherings of WHO Indigenous Peoples from across North America, celebrating 2017 the unifying power of sport. 2017 NAIG is hosting a prestigious multi-sport and cultural event celebrating Indigenous heritage, diversity over 8 NAIG WHAT days, featuring 14 sport categories. WHEN July 16-23, 2017 FACT World-class sport venues • Humber College including: • McMaster University WHERE • Allan A. Lamport • Toronto International Regatta Course Trap & Skeet Club • Don Valley Golf Course • Toronto Pan Am SHEET • Gaylord Powless Sports Centre Arena & Iroquois • Turner Park (Hamilton) Lacrosse Arena • University of Toronto • Hamilton Angling and Scarborough Hunting Association • York University To showcase Unity, Sport, Youth and Heritage between WHY First Nations, Métis and non-Indigenous communities. SPORTS INCLUDE: 2 NORTH AMERICAN INDIGENOUS GAMES 2017 PARTICIPATING TEAMS Alberta British Columbia California Colorado Connecticut Eastern Door and the North Florida Manitoba New Brunswick Newfoundland and Labrador New York Northwest Territories Nova Scotia Nunavut Ontario Prince Edward Island Saskatchewan Washington Wisconsin Yukon (With over 5000 athletes, coaches and offi cials, and more than 2000 volunteers participating) SPONSOR OPPORTUNITIES Custom sponsor packages available based on goals and budget. ADVERTISING AND MARKETING NAIG’S With a marketing budget of over $600,000, the 2017 NAIG Host Society can generate signifi cant COMMITMENT media attention for elite level sponsors. #ALLONE The North American Indigenous Games will unite individuals and communities across North America through sport to celebrate our past (heritage), present (unity) and future (youth). -

A Comparison of the Native Casino Gambling Policy in Alberta and Saskatchewan

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Alberta Gambling Research Institute Alberta Gambling Research Institute 1996-10 Time to deal : a comparison of the Native casino gambling policy in Alberta and Saskatchewan Skea, Warren H. University of Calgary http://hdl.handle.net/1880/540 Thesis Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY, •> Time to Deal: A Comparison of the Native Casino Gambling ..'•".' -' Policy in Alberta and Saskatchewan _ • by Warren H. Skea A DISSERTATION • SUBMIfTED TO" THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUPIES ," \' ' - FULFILLMENT_OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEEARTMENT OF S9CIOLOQY » fc ."*•-•"•'•.-.--•.• -•' * ' ' ' * * •\ ' \. CALGARY-,^- ALBERTA - *. OCTOBER, 1996 * r -. ft **- " * ••*' ; -* * r * * :•'• -r? :' ' ' /'—^~ (ctWarren H, Skea 1996 W/ ' V National Library Btoliotheque national 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 WeWnflton StrMt 395. rue Welington Ottawa ON K1AON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 • Canada your tit Varf q The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence .allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque rationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of his/her thesis by any means vendre des copies de sa these de and in any form or format, making quelque maniere et sous quelque , this thesis available to interested forme que ce soit pour mettre des persons. exemplaires.de cette these a la disposition des personnes interessees. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in his/her thesis. Neither droit d'auteur qui protege sa these. -

Translating Indigeneity at the University of Alberta Anne Malena and Julie Tarif

Document generated on 09/26/2021 10:46 p.m. TTR Traduction, terminologie, rédaction Translating Indigeneity at the University of Alberta Anne Malena and Julie Tarif Minorité, migration et rencontres interculturelles : du binarisme à la Article abstract complexité Over the last few years there has been an attempt to redress the asymmetrical Minority and Migrant Intercultural Encounters: From Binarisms to relations between Canada’s First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people, and the Complexity non-Indigenous people in Canada. Post-secondary education plays a prominent Volume 31, Number 2, 2e semestre 2018 role in this endeavour and many institutions across Canada are currently working on innovative ways to make their environment more inclusive, or URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065568ar what is called “Indigenizing” the academy. This study focuses on how the University of Alberta (Edmonton) is meeting this challenge and argues that a DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1065568ar form of activist translation needs to be an important part of this endeavour in order to redress damages caused by colonialism. See table of contents Publisher(s) Association canadienne de traductologie ISSN 0835-8443 (print) 1708-2188 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Malena, A. & Tarif, J. (2018). Translating Indigeneity at the University of Alberta. TTR, 31(2), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065568ar Tous droits réservés © Anne Malena et Julie Tardif, 2019 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

1219 Head: Tabling Returns and Reports Point of Order Insulting Language the Speaker: the Hon

May 4, 2004 Alberta Hansard 1209 Legislative Assembly of Alberta Mr. Speaker, among the Queen’s Golden Jubilee Citizenship Medal recipients for 2003 are Samantha Saretsky from Lacombe Title: Tuesday, May 4, 2004 1:30 p.m. composite high school in Lacombe, Alberta. Samantha is accompa- Date: 2004/05/04 nied by her parents, Tony and Marilyn Saretsky. She is currently [The Speaker in the chair] attending the University of Saskatchewan, or was until about the end of April, in political studies. She was joined today by the hon. head: Prayers Member for Lacombe-Stettler, the chair of the Standing Policy Committee on Justice and Government Services. The Speaker: Good afternoon. We also have Laura Abday from Edmonton’s Jasper Place high Let us pray. We give thanks for the bounty of our province: our school. She is currently attending the University of Alberta in land, our resources, and our people. We pledge ourselves to act as atmospheric sciences. She was joined today by the hon. Member for good stewards on behalf of all the people of this province. Amen. Edmonton-McClung, the Minister of Economic Development. Please be seated. We have Evan Wisniewski from Hairy Hill, Alberta, graduating from the Two Hills high school. Evan is here with his parents, Orest head: Introduction of Visitors and Rosemarie Wisniewski. He is studying engineering at the The Speaker: Hon. members, I’m honoured today to introduce you University of Alberta. He was joined today by the hon. Member for to a group of 15 former Members of Parliament from British Vegreville-Viking, the Minister of Transportation. -

Inside This Week

INSIDE THIS WEEK Feds sue province over Lubicon claim "Tell them Willie xiy is here!" BY DOROTHY SCHREIBER before there have been any Hobbema's Littlechild Windspeaker Staff Writer meaningful negotiations." itit.,seeking PC The federal government minution. See PROVINCIAL filed a statement of claim in 'Page 2. Federal legal action the Courts of Queens against Alberta and the Bench in Calgary on May Lubicon Indians may.-not 17 proposing the band leave the band any choice receive 45 square miles of but to assert jurisdiction land (117 square km) and over the disputed land says declaring the province in Chief Bernard Ominayak. breach of its obligations to "Their goal is to tie us up provide the Lubicon people in the courts and delay and with a reserve under the 1 delay," says the Cree chief 1930 Constitution Act. indicating the recent lawsuit In a prepared statement is pushing the band closer the minister of Indian to taking control over a Affairs Bill McKnight said 16,000 square km area negotiations with the band under Aboriginal claim by and the province "proved n:- the band. impossible...and in the LOOKS COMPLEX ENOUGH! Samson boxer He says the band made absence of prospects for a This youngster, Gary Starr, is getting an early start in a difficult and exacting ith Nepoose is only the decision earlier this negotiated settlement this :ask performing the hoop dance. The 16- year -old demonstrated his talents last e of many winners year but decided to put can only be achieved with ekend at a Hobbema powwow to raise gas money to get home on. -

2020 Ermineskin Cree Nation Chief Election Special Edition Newsletter Friday, August 7, 2020

2020 Ermineskin Cree Nation Chief Election Special Edition Newsletter Friday, August 7, 2020 Reasons to Vote in the Upcoming Election If you think you are too small to make a difference, try to sleep in 1. Your Vote is Your Voice. Be Heard! a closed room with a mosquito - African Proverb 2. People we elect make huge decisions that shape our lives daily. Always vote for principle, 3. People in much of the world envy our ability to though you may vote alone, you may cherish the sweet- vote freely. est reflection that your vote 4. Vote the change you want to see in the world! is never lost - John Quincy Ad- 5. Change will not take place without political ams If you don’t vote, you participation. lose the right to com- 6. Every Election is determined by the people plain - George Carlin who show up. Bad officials are elected 7. Voting allows you to express your feelings and by good citizens who opinions about current leaders don’t vote- George Nathan Laurelle White Good afternoon everyone, it is a pleasure to you have to ask for permission when they be here and address everyone and your con- were put here on the reserve, they weren’t al- cerns. First of all I want to thank some of the lowed to leave. You had to ask for permission. elders I have spoken to regarding running and When we were put here, you could not sell their encouragement to me. First one is Willie your cattle, you could not sell anything with- littlechild when I went to speak to him, he out permission, you could not hire a lawyer to liked what I have to say and he encouraged defend you, and we had men from this com- me to continue going forth. -

Dene Woman Faces Risks, Gets Law Degree Have to Be Licenced - to Place the Native and Hard - to -Place Children Much by Keith Matthew A.H

August 12, 198 ., Volume 6 No. 2 Kids win, mothers lose, with new law By Patrick Michell that Native children are Windspeaker Correspondent protected from agencies attempting to place them EDMONTON, Alta. with non -Native families, but points out that a fight Although social workers could erupt between a are opposed to 'it, Native mother and her Alberta's Native children band. may benefit from recent An adoption agency amendments allowing for approached by a pregnant private adoption in the Native woman wishing to province, said a university surrender her unborn child professor. would have to notify the The recent amendments woman's band. d game expertise offer Native children slated "And at that point, the Vermilion's 4 for adoption more protec- band would presumably be Though the competition was fierce and players had bicentennial celebrations August -7. For more the tion than non -Native chil- able to say, 'Well here is to concentrate especially hard, old timers Alphonse coverage of celebrations see pages 10 and 11. dren, says Gayle Gilchrist what we think should be Scha -sees and Patrick Scha -sees managed to nab second Photo by Terry James, associate social wel- done on behalf of the child. place. The games were a popular attraction at Fort Lusty fare professor at the "The woman would still University of Calgary. have the choice, but she could say that 'I will go still "Both INSIDE THIS WEEK in the new act go ahead,' but the band and under the new amend- could also contest it," said ments, Native children are Melsness. -

Beyond the Hill Fall15.Pdf

Muskoka Reception Muskoka, Ontario, Aug 30 - Sept 1, 2015 Photos by Susan Simms and Gina Chambers Relaxing on the Hon. Paul and Sandra Hellyer’s dock during the CAFP reception in Muskoka. Ed Harper, Nanette Zwicker and Hon. Trevor Hon. Peter Milliken examines a beautiful John and Julia Murphy at Muskoka Boat Eyton at Dr. Bethune Interpretation Centre. handmade canoe. & Heritage Centre Ron and Marlene Catterall, Carol Shepherd and Serge Ménard. Norwegian Ambassador Mona Brother at Little Norway Memorial. Page 2 Beyond the Hill • Fall 2015 Beyond the Hill • Fall 2015 Page 3 Beyond the Hill Canadian Association of Former Parliamentarians Volume 12, Issue No. 1 FALL 2015 CONTENTS Reception in Vancouver 26 Regional Meeting in Muskoka 2 Photo by Susan Simms Photos by Susan Simms and Gina Chambers It Seems to me: Social media has CAFP News 4 the power to change everything 27 How the President sees it 5 By Dorothy Dobbie By Hon. Andy Mitchell Magna Carta turns 800 28 Executive Director’s Report 6 By Harrison Lowman By Jack Silverstone Former MP takes on leadership of Distinguished Service Award 7 Alberta’s Wildrose Party 30 Story by Scott Hitchcox, By Hayley Chazan photos by Harrison Lowman Prayer Breakfast still strong after 50 years 31 CAFP Memorial Service 8 By Scott Hitchcox Story by Harrison Lowman, photos by Neil Valois Photography Where are they now? 32 By Hayley Chazan, Scott Hitchcox Chief Willie Littlechild brings Truth and and Harrison Lowman Reconciliation to the AGM 10 By Scott Hitchcox Former B.C. Premier awarded Courage Medal 34 By Hayley Chazan All good news at this year’s AGM 12 Story by Scott Hitchcox How it works 35 AGM Policy Conference 16 By Hon. -

May 7, 2021 Dear School Council Member, It Gives Me Great Pleasure

May 7, 2021 Dear School Council Member, It gives me great pleasure to extend to you for the first time ever an invitation to join our Spring General Assembly for the Public School Boards’ Association of Alberta. Due to the COVID pandemic we have been holding our meetings virtually and have been able to offer Boards a special rate to attend. Your attendance would be included with your Board’s registration and, as such, there would be no additional cost for your attendance. Many of PSBAA’s trustees have attended your Association’s AGM and we thought you might appreciate an invitation to attend one of our meetings. With an election on the horizon and many “things” going on in education today we thought it would be an opportune time to have you join us to get a glimpse of some of what we do outside of our board rooms to support Public Education. On June 3rd • Our researcher, Curtis Riep, will provide commentary on his research paper, A Review of K-12 Education Funding in Alberta. • PSBAA Special Recognition Awards ceremony. • Presentation by Doug Griffiths, author of 13 Ways. He will address The Arrival of the Inevitable. On June 4th • We begin the day by highlighting four of the wonderful programs of choice offered by our member Boards. • We complete the SGA with Chief Willie Littlechild, a Cree lawyer and Chief, former Grand Chief of the Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations, former Member of Parliament, residential school survivor and former commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, who will speak on his involvement in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and his experience in a residential school. -

Inter Indigenous Resource Development

International Organization of Indigenous Resource Development An NGO in consultative status to the United Nations Economic and Social Council COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sub Commission of Prevention of Descrimination and Protection of Minorities Working Group on Indigenous Peoples Seventeenth Session. 26-30 July 1999 United Nations, Geneva RE: AGENDA ITEM 8; CONSIDERATION OF THE FINAL REPORT OF THE SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR OF THE SUB-COMMISSION ON TREATIES Thank you. This is a joint statement of the Four Cree Nations of Hobbema. IOIRD, Paul Nakoda Nation. Confederacy of Treaty 6 Chiefs. Grand Council of Crees, the Treaty 4 Secretariat, the International Indian Treaty Council. Indigenous World Association and Movimiento de la Juventud Kuna. Madame Chairperson, as this is the International Year of Older Persons we would like to acknowledge all our elders, those who have gone onto their spirit journey and those who we are still blessed with today. It was they who kept mother earth for us. It was they who negotiated the Treaty for us for which we are eternally grateful. They were and still are our Treaty Keepers. Thank you again Professor Miguel Alfonso Martinez for your Decade of work. As you know, while we meet here, there is also a Cree Nation Gathering back home on the Ermineskin Cree Nation and your Report is being discussed. Prior to that the Assembly of First Nations, at a meeting with the National Congress of American Indians in Vancouver (July 20-23/99) passed a Resolution moved by Chief Gerry Ermineskin (Treaty 6) and seconded by Chief Delburt Wapass, (Thunderchild) (Treaty 6), to approve the UN INTERNATIONAL TREATY STUDY Resolution as follows: Resolution No.