Growing up in Kelvington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup Calgary Flames Edmonton Oilers St. Louis Blues 2 Flames logo 50 Oilers logo 98 Blues logo 3 Flames uniform 51 Oilers uniform 99 Blues uniform 4 Mike Vernon 52 Grant Fuhr 100 Greg Millen 5 Al MacInnis 53 Charlie Huddy 101 Brian Benning 6 Brad McCrimmon 54 Kevin Lowe 102 Gordie Roberts 7 Gary Suter 55 Steve Smith 103 Gino Cavallini 8 Mike Bullard 56 Jeff Beukeboom 104 Bernie Federko 9 Hakan Loob 57 Glenn Anderson 105 Doug Gilmour 10 Lanny McDonald 58 Wayne Gretzky 106 Tony Hrkac 11 Joe Mullen 59 Jari Kurri 107 Brett Hull 12 Joe Nieuwendyk 60 Craig MacTavish 108 Mark Hunter 13 Joel Otto 61 Mark Messier 109 Tony McKegney 14 Jim Peplinski 62 Craig Simpson 110 Rick Meagher 15 Gary Roberts 63 Esa Tikkanen 111 Brian Sutter 16 Flames team photo (left) 64 Oilers team photo (left) 112 Blues team photo (left) 17 Flames team photo (right) 65 Oilers team photo (right) 113 Blues team photo (right) Chicago Blackhawks Los Angeles Kings Toronto Maple Leafs 18 Blackhawks logo 66 Kings logo 114 Maple Leafs logo 19 Blackhawks uniform 67 Kings uniform 115 Maple Leafs uniform 20 Bob Mason 68 Glenn Healy 116 Alan Bester 21 Darren Pang 69 Rolie Melanson 117 Ken Wregget 22 Bob Murray 70 Steve Duchense 118 Al Iafrate 23 Gary Nylund 71 Tom Laidlaw 119 Luke Richardson 24 Doug Wilson 72 Jay Wells 120 Borje Salming 25 Dirk Graham 73 Mike Allison 121 Wendel Clark 26 Steve Larmer 74 Bobby Carpenter 122 Russ Courtnall 27 Troy Murray -

Nhl Morning Skate – Nov

NHL MORNING SKATE – NOV. 25, 2018 SATURDAY’S RESULTS Home Team in Caps Washington 5, NY RANGERS 3 TORONTO 6, Philadelphia 0 Boston 3, MONTREAL 2, Buffalo 3, DETROIT 2 (SO) Chicago 5, FLORIDA 4 (OT) NY ISLANDERS 4, Carolina 1 PITTSBURGH 4, Columbus 2 Winnipeg 8, ST. LOUIS 4 COLORADO 3, Dallas 2 VEGAS 6, San Jose 0 Vancouver 4, LOS ANGELES 2 LAINE BREAKS RECORDS WITH FIRST FIVE-GOAL GAME IN NEARLY EIGHT YEARS Patrik Laine became the first NHL player in nearly eight years to score five goals in a game, setting franchise records for most in a game and calendar month to take sole possession of the League lead this season (19). He has scored 16 times since returning to his native Finland for the 2018 NHL Global Series on Nov. 1 - where he scored his first of three hat tricks this month. * Laine tallied the 57th performance of five or more goals in a NHL regular-season game – the 17th by a visiting player - and first since Detroit’s Johan Franzen on Feb. 2, 2011 at OTT. The only other player to score five goals in a game since 1997-98 is Marian Gaborik, on Dec. 20, 2007 vs. NYR. * Laine (20 years, 219 days) is the third different player in League history to score five goals in a game before his 21st birthday, joining Don Murdoch (Oct. 12, 1976: 19 years, 353 days) and Wayne Gretzky, who accomplished the feat twice (Feb. 18, 1981: 20 years, 23 days; and Dec. 30, 1981: 20 years, 338 days). -

AN HONOURED PAST... and Bright Future an HONOURED PAST

2012 Induction Saturday, June 16, 2012 Convention Hall, Conexus Arts Centre, 200 Lakeshore Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan AN HONOURED PAST... and bright future AN HONOURED PAST... and bright future 2012 Induction Saturday, June 16, 2012 Convention Hall , Conexus Arts Centre, 200 Lakeshore Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan INDUCTION PROGRAM THE SASKATCHEWAN Master of Ceremonies: SPORTS HALL OF FAME Rod Pedersen 2011-12 Parade of Inductees BOARD OF DIRECTORS President: Hugh Vassos INDUCTION CEREMONY Vice President: Trent Fraser Treasurer: Reid Mossing Fiona Smith-Bell - Hockey Secretary: Scott Waters Don Clark - Wrestling Past President: Paul Spasoff Orland Kurtenbach - Hockey DIRECTORS: Darcey Busse - Volleyball Linda Burnham Judy Peddle - Athletics Steve Chisholm Donna Veale - Softball Jim Dundas Karin Lofstrom - Multi Sport Brooks Findlay Greg Indzeoski Vanessa Monar Enweani - Athletics Shirley Kowalski 2007 Saskatchewan Roughrider Football Team Scott MacQuarrie Michael Mintenko - Swimming Vance McNab Nomination Process Inductee Eligibility is as follows: ATHLETE: * Nominees must have represented sport with distinction in athletic competition; both in Saskatchewan and outside the province; or whose example has brought great credit to the sport and high respect for the individual; and whose conduct will not bring discredit to the SSHF. * Nominees must have compiled an outstanding record in one or more sports. * Nominees must be individuals with substantial connections to Saskatchewan. * Nominees do not have to be first recognized by a local satellite hall of fame, if available. * The Junior level of competition will be the minimum level of accomplishment considered for eligibility. * Regardless of age, if an individual competes in an open competition, a nomination will be considered. * Generally speaking, athletes will not be inducted for at least three (3) years after they have finished competing (retired). -

Weekend with a Legend

Weekend with a Legend Participate in the Ultimate Hockey Fan Experience and spend the weekend playing with some of hockey’s greatest Legends. This experience will allow you to draft your favorite hockey Legend to become apart of your team for the weekend. This means they will play in all of your scheduled tournament games, hang-out in the dressing room sharing stories of their careers, and take in the nightlife with the team. All you have to do is select a player from the list below or request a player that you don’t see and we will do our best to accommodate your group with the 100+ other Legends that have participated in our events. Golden Legends- starting @ $365cdn/ per person (based on a team of 20). $7,300/ per team. Al Iafrate (Toronto Maple Leafs) Gary Leeman (Toronto Maple Leafs) Chris “Knuckles” Nilan (Montreal Canadiens) John Scott (Arizona Coyotes) Bob Sweeney (Boston Bruins) Natalie Spooner (Canadian Olympic Team) Andrew Raycroft (Toronto Maple Leafs) Ron Duguay (New York Rangers) Darren Langdon (New York Rangers) Colton Orr (Toronto Maple Leafs) Dennis Maruk (Washington Capitals) Chris Kotsopoulos (Hartford Whalers) John Leclair (Philadelphia Flyers) Colin White (New Jersey Devils) Kevin Stevens (Pittsburgh Penguins) Shane Corson (Toronto Maple Leafs) Mike Krushelnyski (Edmonton Oilers) Theo Fleury (Calgary Flames) Many More………. Platinum Legends- starting @ $665cdn/ per person (based on a team of 20). $20,000cdn/ per team. Ray Bourque (Boston Bruins) Wendel Clark (Toronto Maple Leafs) Guy Lafleur (Coach) (Montreal Canadiens) Bryan Trottier (New York Islanders) Steve Shutt (Montreal Canadiens) Bernie Nicholls (LA Kings) Many More………. -

1980-81 Topps Hockey Card Set Checklist

1980-81 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Philadelphia Flyers (Record Breaker) 2 Ray Bourque (Record Breaker) 3 Wayne Gretzky (Record Breaker) 4 Charlie Simmer (Record Breaker) 5 Billy Smith (Record Breaker) 6 Jean Ratelle 7 Dave Maloney 8 Phil Myre 9 Ken Morrow 10 Guy Lafleur 11 Bill Derlago 12 Doug Wilson 13 Craig Ramsay 14 Pat Boutette 15 Eric Vail 16 Mike Foligno 17 Bobby Smith 18 Rick Kehoe 19 Joel Quenneville 20 Marcel Dionne 21 Kevin McCarthy 22 Jim Craig 23 Steve Vickers 24 Ken Linseman 25 Mike Bossy 26 Serge Savard 27 Grant Mulvey (Checklist) 28 Pat Hickey 29 Peter Sullivan 30 Blaine Stoughton 31 Mike Liut 32 Blair MacDonald 33 Rick Green 34 Al Macadam 35 Robbie Ftorek 36 Dick Redmond 37 Ron Duguay 38 Danny Gare (Checklist) 39 Brian Propp 40 Bryan Trottier 41 Rich Preston 42 Pierre Mondou Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Reed Larson 44 George Ferguson 45 Guy Chouinard 46 Billy Harris 47 Gilles Meloche 48 Blair Chapman 49 Mike Gartner (Checklist) 50 Darryl Sittler 51 Richard Martin 52 Ivan Boldirev 53 Craig Norwich 54 Dennis Polonich 55 Bobby Clarke 56 Terry O'Reilly 57 Carol Vadnais 58 Bob Gainey 59 Blaine Stoughton (Checklist) 60 Billy Smith 61 Mike O'Connell 62 Lanny McDonald 63 Lee Fogolin 64 Rocky Saganiuk 65 Rolf Edberg 66 Paul Shmyr 67 Michel Goulet 68 Dan Bouchard 69 Mark Johnson 70 Reggie Leach 71 Bernie Federko (Checklist) 72 Peter Mahovlich 73 Anders Hedberg 74 Brad Park 75 Clark Gillies 76 Doug Jarvis 77 John Garrett 78 Dave Hutchison 79 John Anderson 80 Gilbert Perreault 81 Marcel Dionne (All-Star) -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award ................................................................................................. -

SELLER MANAGED Downsizing Online Auction - Mill Street

09/29/21 09:38:06 Port Hope (Ontario, Canada) SELLER MANAGED Downsizing Online Auction - Mill Street Auction Opens: Thu, Dec 31 5:00pm ET Auction Closes: Wed, Jan 13 9:00pm ET Lot Title Lot Title 300 Very Rare Paul Gillis "Bleeding Nose" Error 332 High Quality, Heavy Duty, Mint Condition Card 333 Some Of The Coolest Looking Cards Ever Made 301 4 Old Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Cards 334 Grant Fuhr 302 7 More Old BBall Cards 335 Eddie's Iconic Mask 303 Pippen, Marbury & More 336 Mike Richter 304 2003 McDonalds Die Cuts 337 Cheveldae 305 O.P.C. Russian Subset Cards 338 Andy Moog 306 A Dozen Rookie Cards 339 Beaupre's Brain Bucket 307 (58) 1978/79 OPC Cards 340 Painted Warriors... #6 Of 10 308 Ken Dryden's Last Card 341 Painted Warrior 309 Bossy, Bossy, Espo 342 Painted Warrior 310 Curtis Joseph Signed Picture 343 Painted Warriors 311 "The Cat" Felix Potvin 344 Painted Warriors 312 Early Shaq Books 345 Painted Warriors 313 1998 UD McD's Cards 346 Painted Warriors 314 Complete Set # 1- 40 347 Painted Warriors #8 315 Brian Trottier 348 More Great Looking Mask Cards 316 Searching For Bobby Orr (???) 349 These Are Cool Too! 317 A Little Piece Of Canadian Hockey History 350 1979/80 OPC Cards 318 Guess Who ??? 351 Billy Guerin, Stu Barnes And Kris Draper 319 78/79 Shut Out Leaders 352 Vintage Tony Esposito Card 320 78/79 Goals Against Leaders 353 Trottier x 2 321 Charlie Simmer Rookie Card 354 Bobby Clarke 323 1990 - 91 Upper Deck Factory Set 355 Leafs Team Circa 1992 324 Dave Taylor RC. -

Rifle Submission.Pdf

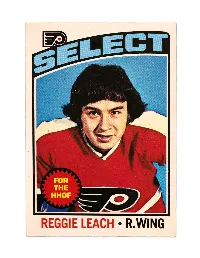

John K. Samson PO Box 83‐971 Corydon Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba R3M 3S3 February 23, 2013 Mr. Bill Hay, Chairman of the Board, and Members of the Selection Committee The Hockey Hall of Fame 30 Yonge Street Toronto, Ontario M5V 1X8 Dear Mr. Bill Hay, Chairman of the Board, and Members of the Selection Committee, Hockey Hall of Fame; In accordance with the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Policy Regarding Public Submission of Candidates Eligible for Election into Honoured Membership, please accept this bona‐fide submission putting forth the name Reggie Joseph Leach for your consideration. A member of the Berens River First Nation, Reggie Joseph Leach was born in 1950 in Riverton, Manitoba. While facing the injustices of racism and poverty, and playing on borrowed skates for much of his childhood, Leach’s terrific speed and honed shooting skills earned him the nickname “The Riverton Rifle.” He went on to become one of the most gifted and exciting hockey players of his generation. His pro‐hockey accomplishments are truly impressive: two‐time NHL All Star, Conn Smythe Trophy winner (the only non‐goalie from a losing team to ever win it), 1975 Stanley Cup winner, 1976 Canada Cup winner, and Regular Season Goal Scoring Leader, to name a few. His minor league record is remarkable, too. As a legendary member of the MJHL/WCJHL Flin Flon Bombers, Mr. Leach led the league in goal‐scoring twice, and was placed on the First All‐ Star team every season he played. The statistical analysis in the pages that follow, prepared by Phil Russell of Dozen Able Men Data Design (Ottawa, Ontario), makes a clear and persuasive case that Mr. -

2018-19 St. Louis Blues

2018-19 ST. LOUIS BLUES PLAYOFF QUICK HITS Playoff History All-Time Playoff Appearance: 42nd Consecutive Playoff Appearance: 0 Most Recent Playoff Appearance: 2017 (FR: 4-1 W vs. MIN; SR: 4-2 L vs. NSH) All-Time Playoff Record: 164-201 in 365 GP (27-41 in 68 series) Playoff Records Game 7s: 8-8 (4-2 at home, 4-6 on road) Overtime: 35-31 (24-14 at home, 11-17 on road) Facing Elimination: 28-41 (18-15 at home, 10-26 on road) With Chance to Clinch Series: 27-26 (14-9 at home, 13-17 on road) Stanley Cup Final Stanley Cup Final Appearances: 3 Stanley Cups: 0 Link Stanley Cup Champions Playoff Skater Records All-Time Playoff Formats Playoff Goaltender Records All-Time Playoff Standings Playoff Team Records St. Louis Blues: Year-by-Year Record (playoffs at bottom) St. Louis Blues: All-Time Record vs. Opponents (playoffs at bottom) LOOKING AHEAD: 2019 STANLEY CUP PLAYOFFS Team Notes * Owners of the third-longest playoff streak in NHL history at 25 seasons (1979-80 to 2003-04; tied), St. Louis now returns to the postseason for the seventh time in the last eight seasons (since 2011-12). * The Blues have the seventh-most playoff appearances in NHL history (42) and the most among non- Original Six teams, ahead of the Flyers (39), Penguins (33), Stars/North Stars (31) and Kings (30). * St. Louis now is 35th team in NHL history to reach the postseason after ranking last in the overall standings at any point after their 20th game. -

NHL 19 Legends

NHL 19 Legends - Skaters Aaron Broten Adam Graves Adam Hall Adam Oates Adrian Aucoin Al Iafrate Al MacInnis Alyn McCauley Andrew Alberts Andrew Cassels Andy Bathgate Bernie Federko Bernie Geoffrion Bill Barber Blaine Stoughton Blake Dunlop Bob Nystrom Bob Probert Bobby Carpenter Bobby Clarke Bobby Holik Bobby Hull Borje Salming Brad Maxwell Brad Park Brendan Morrison Brett Hull Brian Bellows Brian Bradley Brian Leetch Brian McGrattan Brian Propp Bryan Marchment Bryan Trottier Butch Goring Cale Hulse Charlie Conacher Chris Chelios Chris Clark Chris Nilan Chris Phillips Chris Pronger Christoph Brandner Chuck Kobasew Clark Gillies Claude Lemieux Cliff Koroll Cory Cross Craig Hartsburg Craig Ludwig Craig Simpson Curtis Leschyshyn Dale Hawerchuk Dallas Smith Dan Quinn Darren McCarty Darryl Sittler Dave Andreychuk Dave Babych Dave Ellett Denis Potvin Denis Savard Dennis Hull Dennis Maruk Derek Plante Dick Duff Don Marcotte Donald Awrey Doug Bodger Doug Gilmour Douglas Brown Earl Sr. Ingarfield Ed Olczyk Errol Thompson Frank Mahovlich Garry Unger Garry Valk Garth Butcher Gary Dornhoefer Gary Roberts Glenn Anderson Gord Murphy Grant Marshall Guy Carbonneau Guy Lafleur Harry Howell Henri Richard Howie Morenz Igor Larionov Jamie Langenbrunner Jari Kurri Jason Arnott Jean Beliveau Jean Ratelle Jeff Beukeboom Jere Lehtinen Jeremy Roenick Jim Dowd Jody Hull Jody Shelley Joe Nieuwendyk Joe Sakic Joe Watson Joel Otto Joey Kocur John Carter John MacLean John Marks John Ogrodnick Johnny Bucyk Jyrki Lumme Keith Brown Keith Carney Keith Primeau Keith Tkachuk -

1989-90 Topps Hockey 198 Cards

1989-90 Topps Hockey 198 cards 1 Mario Lemieux 51 Glen Wesley 101 Shawn Burr 151 Marc Habscheid RC 2 Ulf Dahlen 52 Dirk Graham 102 John MacLean 152 Dan Quinn 3 Terry Carkner RC 53 G. Carbonneau 103 Tom Fergus 153 Stephane Richer 4 Tony McKegney 54 T. Sandstrom 104 Mike Krushelnyski 154 Doug Bodger 5 Denis Savard 55 Rod Langway 105 Gary Nylund 155 Ron Hextall 6 Derek King RC 56 P. Sundstrom 106 Dave Andreychuk 156 Wayne Gretzky 7 Lanny McDonald 57 Michel Goulet 107 Bernie Federko 157 Steve Tuttle RC 8 John Tonelli 58 Dave Taylor 108 Gary Suter 158 Charlie Huddy 9 Tom Kurvers 59 Phil Housley 109 Dave Gagner 159 Dave Christian 10 Dave Archibald 60 Pat LaFontaine 110 Ray Bourque 160 Andy Moog 11 P. Sidorkiewicz RC 61 Kirk McLean RC 111 Geoff Courtnall RC 161 Tony Granato RC 12 Esa Tikkanen 62 Ken Linseman 112 Doug Wilson 162 Sylvain Cote RC 13 Dave Barr 63 R. Cunneyworth 113 Joe Sakic RC 163 Mike Vernon 14 Brent Sutter 64 Tony Hrkac 114 John Vanbiesbrouck 164 Steve Chiasson RC 15 Cam Neely 65 Mark Messier 115 Dave Poulin 165 Mike Ridley 16 C. Johansson RC 66 Carey Wilson 116 Rick Meagher 166 Kelly Hrudey 17 Patrick Roy 67 Steve Leach RC 117 Kirk Muller 167 Bobby Carpenter 18 Dale DeGray RC 68 Christian Ruuttu 118 Mats Naslund 168 Zarley Zalapski RC 19 Phil Bourque RC 69 Dave Ellett 119 Ray Sheppard 169 Derek Laxdal RC 20 Kevin Dineen 70 Ray Ferraro 120 Jeff Norton RC 170 Clint Malarchuk 21 Mike Bullard 71 Colin Patterson RC 121 Randy Burridge 171 Kelly Kisio -

Hockey Trivia Answers 1. Answer

Hockey Trivia Answers 1. Answer: c. Floral, SK. Gordie was born in a farmhouse in Floral, SK which was just south of Saskatoon. His family moved to Saskatoon when Gordie was 9 days old. 2. Answer: a. Clark Gillies, Dennis Sobchuk, Ed Staniowski. All three of these great Regina Pats have gone on to NHL careers and have had their numbers retired by the Pats. 3. Answer: d. Mike Wirachowsky, Kim MacDougall. Although Kim MacDougall only played one game in the NHL, both players had great minor league careers with several teams. 4. Answer: b. Colleen Sostorics and Fiona Smith Bell. Colleen Sostorics was part of the Canadian National Team winning 3 Olympic gold medals and many other international medals. Fiona Smith Bell was a member of the Canadian National Team as well and captured an Olympic silver medal. 5. Answer: c. Those who died fighting for Canada in conflict. Established by Captain James T. Sutherland to honour those men who gave their lives during World War I. It was rededicated during the 2010 tournament to honour all soldiers who died fighting for Canada in any conflict. 6. Answer: a. Bryan Trottier. Trottier earned 7 Stanley cups, 6 as a player with the New York Islanders (4) the Pittsburgh Penguins (2). He also won one as a coach with the Colorado Avalanche. 7. Answer: d. Gordie Howe. Howe played 26 seasons in the National Hockey League and 6 in the World Hockey Association. He is considered one of the most complete hockey players to ever play the game. 8. Answer: b.