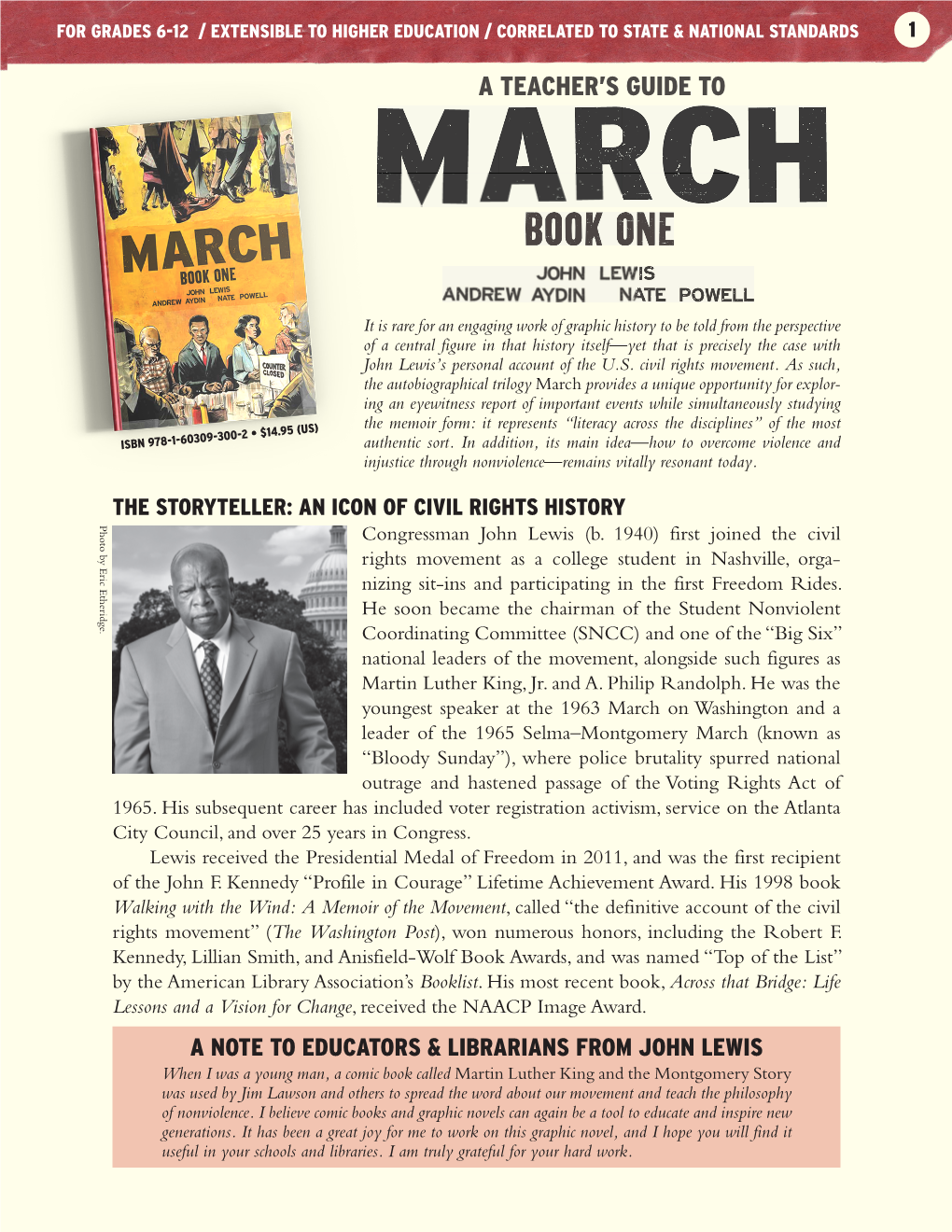

A Teacher's Guide To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

The "Stars for Freedom" Rally

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Selma-to-Montgomery National Historic Trail The "Stars for Freedom" Rally March 24,1965 The "March to Montgomery" held the promise of fulfilling the hopes of many Americans who desired to witness the reality of freedom and liberty for all citizens. It was a movement which drew many luminaries of American society, including internationally-known performers and artists. In a drenching rain, on the fourth day, March 24th, carloads and busloads of participants joined the march as U.S. Highway 80 widened to four lanes, thus allowing a greater volume of participants than the court- imposed 300-person limitation when the roadway was narrower. There were many well-known celebrities among the more than 25,000 persons camped on the 36-acre grounds of the City of St. Jude, a Catholic social services complex which included a school, hospital, and other service facilities, located within the Washington Park neighborhood. This fourth campsite, situated on a rain-soaked playing field, held a flatbed trailer that served as a stage and a host of famous participants that provided the scene for an inspirational performance enjoyed by thousands on the dampened grounds. The event was organized and coordinated by the internationally acclaimed activist and screen star Harry Belafonte, on the evening of March 24, 1965. The night "the Stars" came out in Alabama Mr. Belafonte had been an acquaintance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. since 1956. He later raised thousands of dollars in funding support for the Freedom Riders and to bailout many protesters incarcerated during the era, including Dr. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 166 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2020 No. 204 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was These are the people who walked in Doug Hartman, Karen Hasara, Holly called to order by the Speaker pro tem- parades; they helped pass out balloons, Healey, Brian Heckert, Bob pore (Mr. CUELLAR). candy, and political literature; they Hermsmeyer, Dennis Herrington, Nita f carried signs; they put up and took Hill, Mark and Elaine Hoffman, Nancy down political signs of all sizes; they Kimme, Bob Kjellander, Gwen Klinger, DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO helped stuff mail and phone-bank; they Doug Knebel, Lynn Koch, Gale and Pat TEMPORE organized fundraisers, both big and Koelling, Greg Knott, J.C. Kowa, Kel- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- small; they manned booths at county vin Kuneth, Keith and Judy Loemker, fore the House the following commu- fairs. Kay Long, Tom and Robin Long, Sen- nication from the Speaker: What causes people to give up their ator David Luechtefeld, Curt and Lu WASHINGTON, DC, time, their talents and possessions to a Maddox, Tony Marsh, Mark and Carol December 3, 2020. candidate, party, or cause? It is at the Mestemacher, Don and Joanne Metzler, I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY heart of a representative democracy, Guy Michael, Tom and Robin Long. CUELLAR to act as Speaker pro tempore on our constitutional Republic. Kathy Lynch, Kathy Lydon, Andy this day. -

Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr

Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. “Labor, Racism, and Justice in the 21st Century” The 2015 Jerry Wurf Memorial Lecture The Labor and Worklife Program Harvard Law School JERRY WURF MEMORIAL FUND (1982) Harvard Trade Union Program, Harvard Law School The Jerry Wurf Memorial Fund was established in memory of Jerry Wurf, the late President of the American Federation of State, County and Munic- ipal Employees (AFSCME). Its income is used to initiate programs and activities that “reflect Jerry Wurf’s belief in the dignity of work, and his commitment to improving the quality of lives of working people, to free open thought and debate about public policy issues, to informed political action…and to reflect his interests in the quality of management in public service, especially as it assures the ability of workers to do their jobs with maximum effect and efficiency in environments sensitive to their needs and activities.” Jerry Wurf Memorial Lecture February 19, 2015 Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. “Labor, Racism, and Justice in the 21st Century” Table of Contents Introduction Naomi Walker, 4 Assistant to the President of AFSCME Keynote Address Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. 7 “Labor, Racism, and Justice in the 21st Century” Questions and Answers 29 Naomi Walker, Assistant to the President of AFSCME Hi, good afternoon. Who’s ready for spring? I am glad to see all of you here today. The Jerry Wurf Memorial Fund, which is sponsoring this forum today, was established in honor of Jerry Wurf, who was one of AFSCME’s presidents from 1964 till 1981. These were really incredibly formative years for our union and also nationally for this nation. -

Waveland, Mississippi, November 1964: Death of Sncc, Birth of Radicalism

WAVELAND, MISSISSIPPI, NOVEMBER 1964: DEATH OF SNCC, BIRTH OF RADICALISM University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire: History Department History 489: Research Seminar Professor Robert Gough Professor Selika Ducksworth – Lawton, Cooperating Professor Matthew Pronley University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire May 2008 Abstract: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) was a nonviolent direct action organization that participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. After the Freedom Summer, where hundreds of northern volunteers came to participate in voter registration drives among rural blacks, SNCC underwent internal upheaval. The upheaval was centered on the future direction of SNCC. Several staff meetings occurred in the fall of 1964, none more important than the staff retreat in Waveland, Mississippi, in November. Thirty-seven position papers were written before the retreat in order to reflect upon the question of future direction of the organization; however, along with answers about the future direction, these papers also outlined and foreshadowed future trends in radical thought. Most specifically, these trends include race relations within SNCC, which resulted in the emergence of black self-consciousness and an exodus of hundreds of white activists from SNCC. ii Table of Contents: Abstract ii Historiography 1 Introduction to Civil Rights and SNCC 5 Waveland Retreat 16 Position Papers – Racial Tensions 18 Time after Waveland – SNCC’s New Identity 26 Conclusion 29 Bibliography 32 iii Historiography Research can both answer questions and create them. Initially I discovered SNCC though Taylor Branch’s epic volumes on the Civil Right Movements in the 1960s. Further reading revealed the role of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) in the Civil Right Movement and opened the doors into an effective and controversial organization. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

A Mediagraphy Relating to the Black Man

racumEN7 RESUME ED 033 943 IE 001 593 AUTHOR Parker, James E., CcmF. TITLE A Eediagraphy Relating to the Flack Man. INSTITUTION North Carclina Coll., Durham. Pub Date May 69 Note 82F. EDRS Price EDRS Price MF-$0.50 BC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors African Culture, African Histcry, *Instructional Materials, *Mass Media, *Negro Culture, *Negro Histcry, Negro leadership, *Negro Literature, Negro Ycuth, Racial Eiscriminaticn, Slavery Abstract Media dealing with the Black man--his history, art, problems, and aspirations--are listed under 10 headings:(1) disc reccrdings,(2) filmstrips and multimedia kits, (3) microfilms, (4) motion pictures, (5) pictures, Fcsters and charts,(6) reprints,(7) slides, (8) tape reccrdings, (9) telecourses (kinesccFes and videotapes), and (10) transparencies. Rentalcr purchase costs of the materials are usually included, andsources and addresses where materials may be obtainedare appended. [Not available in hard cecy due tc marginal legibility of original dccument.] (JM) MEDIA Relatingto THE BLACKMAN by James E. Parker U.). IMPARIMUll OF !ULM,tOUGAI1011 &WINE OfFKE OF EDUCATION PeN THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON 02 ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS Ci STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION re% POSITION OR POLICY. O1 14.1 A MEDIAGRAPHY RELATING TO THE BLACK MAN Compiled by James E. Parker, Director Audiovisual-Television Center North Carolina College at Durham May, 1969 North Carolina College at Durham Durham, North Carolina 27707 .4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii FOREWORD iii DISC RECORDINGS 1-6 FILMSTRIPS AND MULTIMEDIA KITS 7- 18 MICROFILMS 19- 25 NOTION PICTURES 26- 48 PICTURES, POSTERS, CHARTS. -

Address at Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., Delivered by Coretta Scott King the Martin Luther King, Jr. P

25 Oct vividly, is the vast outpouring of sympathy and affection that came to me literally 1958 from everywhere-from Negro and white, from Catholic, Protestant and Jew, from the simple, the uneducated, the celebraties and the great. I know that this affection was not for me alone. Indeed it was far too much for any one man to de- serve. It was really for you. It was an expression of the fact that the Montgomery Story had moved the hearts of men everywhere. Through me, the many thou- sands of people who wrote of their admiration, were really writing of their love for you. This is worth remembering. This is worth holding on to as we strive on for Freedom. And finally, as I indicated before, the experience I had in New York gave me time to think. I believe that I have sunk deeper the roots of my convic- tion that (non-violent}resistence is the true path for overcoming in- justice and- for stamping out evil. May God bless you. TAD. MLKP-MBU: Box 93. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project Address at Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., Delivered by Coretta Scott King 25 October 1958 New York, N.Y. At the Lincoln Memorial Coretta Scott King delivered these remarks on behalf of her husband to ten thousand people who had marched down Constitution Avenue in support of school integration.’ During the march Harry Belafonte led a small integrated contingent of students to the White House to meet the president. They were met at the gate by a guard who informed them that neither the president nor any of his assistants would be available. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

Biographical Sketch of Fannie Lou Hamer

ERICA AM F E IN C D OI YOUR V Fannie Lou Hamer: A Biographical Sketch By Maegan Parker Brooks, PhD “I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hook because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?” With this critical question, delivered at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Fannie Lou Hamer became revered across the nation. Malcolm X referred to her as the “country’s number one freedom fighting woman” and rumor has it Martin Luther King, Jr—though he loved her dearly— feared being upstaged by Hamer’s soul-stirring speeches. Over her lifetime (1917-1977), Fannie Lou Hamer traveled from the Delta of Mississippi to the Atlantic City Boardwalk, from Washington, D.C. to Washington State, from Madison, Wisconsin to Conakry, Guinea—always proclaiming the social gospel that all human beings are created equal and that all people are entitled to basic rights of food, FIGURE 1: Fannie Lou Hamer addresses the shelter, dignity, and a voice in the government to 1964 Democratic National Convention. which they belong. Fannie Lou Hamer held strong convictions, but she was no idealist. Born the twentieth child of James Lee and Lou Ella Townsend, Fannie Lou and her large family struggled to survive as sharecroppers on plantations controlled by Whites. As an outgrowth of slavery, the sharecropping system was largely designed to keep Black people indebted to White landowners. This economic control held social and political implications as well. -

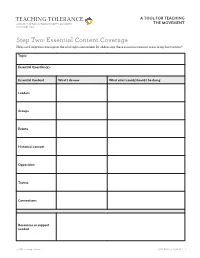

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: Essential Question(s): Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Leaders Groups Events Historical context Opposition Tactics Connections Resources or support needed © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage (SAMPLE) How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should be doing Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy A. Philip Randolph Wilkins, Whitney Young, Dorothy Height Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Groups Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Urban League (NUL), Negro American Labor Council (NALC) The 1963 March on Washington was one of the most visible and influential Some 250,000 people were present for the March Events events of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther on Washington. They marched from the Washington King Jr. -

Teaching the March on Washington

Nearly a quarter-million people descended on the nation’s capital for the 1963 March on Washington. As the signs on the opposite page remind us, the march was not only for civil rights but also for jobs and freedom. Bottom left: Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the historic event, stands with marchers. Bottom right: A. Philip Randolph, the architect of the march, links arms with Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers and the most prominent white labor leader to endorse the march. Teaching the March on Washington O n August 28, 1963, the March on Washington captivated the nation’s attention. Nearly a quarter-million people—African Americans and whites, Christians and Jews, along with those of other races and creeds— gathered in the nation’s capital. They came from across the country to demand equal rights and civil rights, social justice and economic justice, and an end to exploitation and discrimination. After all, the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” was the march’s official name, though with the passage of time, “for Jobs and Freedom” has tended to fade. ; The march was the brainchild of longtime labor leader A. PhilipR andolph, and was organized by Bayard RINGER Rustin, a charismatic civil rights activist. Together, they orchestrated the largest nonviolent, mass protest T in American history. It was a day full of songs and speeches, the most famous of which Martin Luther King : AFP/S Jr. delivered in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial. top 23, 23, GE Last month marked the 50th anniversary of the march.