A Beginner's Guide to Crowley Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIBER ALEPH Vel CXI : the BOOK of WISDOM OR FOLLY

LIBER ALEPH VEL CXI THE BOOK OF WISDOM OR FOLLY in the Form of an Epistle of 666 THE GREAT WILD BEAST to his Son 777 being THE EQUINOX VOLUME III No. vi by THE MASTER THERION (Aleister Crowley) An LVII Sol in 0º 0’ 0” September 23 1961 e.v. 6:19 a.m. Liber Aleph - 2 A.·. A.·. Publication in Class B. Imprimatur N. Fra: A.·. A.·. O.M. 7 = 4 R.R. et A.C. Φ 6 = 5 Imperator Liber Aleph - 3 In Hastings (with little left but pipe and wit) Liber Aleph - 4 ENGLISH LIST OF CHAPTERS 1. APOLOGIA 2. ON THE QABALISTIC ART 3. ON CORRECTING ONE'S LIFE 4. FABLES OF LOVE 5. OF LOVE IN HISTORY 6. A FINAL THESIS ON LOVE 7. ON PERCEIVING ONE'S OWN NATURE 8. MORE ON THE WAY OF NATURE 9. HOW ONE SHOULD CONSIDER ONE'S NATURE 10. ON DREAMS (ACCIDENTAL) 11. ON DREAMS (NATURAL) 12. ON DREAMS (CLOTHED WITH HORROR) 13. ON DREAMS (CONTINUATION) 14. ON DREAMS (THE KEY) 15. ON ASTRAL TRAVEL 16. ON THELEMIC CULT 17. ON THE KEY OF DREAMS 18. ON THE SLEEP OF LIGHT 19. ON POISONS 20. ON THE MOTION OF LIFE 21. ON DISEASES OF THE BLOOD 22. ON THE WAY OF LOVE 23. ON THE MYSTICAL MARRIAGE 24. ON THE JOY OF SORROWS 25. ON THE ULTIMATE WILL 26. ON THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THINGS 27. ON THE HIDDEN WILL 28. ON THE SUPREME FORMULA 29. ON THE WAY OF INERTIA 30. ON THE WAY OP FREEDOM 31. -

The Changing Role of Leah Hirsig in Aleister Crowley's Thelema, 1919

Aries – Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 21 (2021) 69–93 ARIES brill.com/arie Proximal Authority The Changing Role of Leah Hirsig in Aleister Crowley’s Thelema, 1919–1930 Manon Hedenborg White Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden [email protected] Abstract In 1920, the Swiss-American music teacher and occultist Leah Hirsig (1883–1975) was appointed ‘Scarlet Woman’ by the British occultist Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), founder of the religion Thelema. In this role, Hirsig was Crowley’s right-hand woman during a formative period in the Thelemic movement, but her position shifted when Crowley found a new Scarlet Woman in 1924. Hirsig’s importance in Thelema gradually declined, and she distanced herself from the movement in the late 1920s. The article analyses Hirsig’s changing status in Thelema 1919–1930, proposing the term proximal authority as an auxiliary category to MaxWeber’s tripartite typology.Proximal authority is defined as authority ascribed to or enacted by a person based on their real or per- ceived relational closeness to a leader. The article briefly draws on two parallel cases so as to demonstrate the broader applicability of the term in highlighting how relational closeness to a leadership figure can entail considerable yet precarious power. Keywords Aleister Crowley – Leah Hirsig – Max Weber – proximal authority – Thelema 1 Introduction During the reign of Queen Anne of Great Britain (1665–1714), Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough (1660–1744), was the second most powerful woman in the kingdom. As the queen’s favourite, the Duchess overcame many restrictions hampering women of the time. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

OCCULT BOOKS Catalogue No

THOMPSON RARE BOOKS CATALOGUE 45 OCCULT BOOKS Catalogue No. 45. OCCULT BOOKS Folklore, Mythology, Magic, Witchcraft Issued September, 2016, on the occasion of the 30th Anniversary of the Opening of our first Bookshop in Vancouver, BC, September, 1986. Every Item in this catalogue has a direct link to the book on our website, which has secure online ordering for payment using credit cards, PayPal, cheques or Money orders. All Prices are in US Dollars. Postage is extra, at cost. If you wish to view this catalogue directly on our website, go to http://www.thompsonrarebooks.com/shop/thompson/category/Catalogue45.html Thompson Rare Books 5275 Jerow Road Hornby Island, British Columbia Canada V0R 1Z0 Ph: 250-335-1182 Fax: 250-335-2241 Email: [email protected] http://www.ThompsonRareBooks.com Front Cover: Item # 73 Catalogue No. 45 1. ANONYMOUS. COMPENDIUM RARISSIMUM TOTIUS ARTIS MAGICAE SISTEMATISATAE PER CELEBERRIMOS ARTIS HUJUS MAGISTROS. Netherlands: Aeon Sophia Press. 2016. First Aeon Sophia Press Edition. Quarto, publisher's original quarter black leather over grey cloth titled in gilt on front cover, black endpapers. 112 pp, illustrated throughout in full colour. Although unstated, only 20 copies were printed and bound (from correspondence with the publisher). Slight binding flaw (centre pages of the last gathering of pages slightly miss- sewn, a flaw which could be fixed with a spot of glue). A fine copy. ¶ A facsimile of Wellcome MS 1766. In German and Latin. On white, brown and grey-green paper. The title within an ornamental border in wash, with skulls, skeletons and cross-bones. Illustrated with 31 extraordinary water-colour drawings of demons, and three pages of magical and cabbalistic signs and sigils, etc. -

Hitler's Doubles

Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos Fully-Illustrated Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles: Fully-Illustrated By Peter Fotis Kapnistos [email protected] FOT K KAPNISTOS, ICARIAN SEA, GR, 83300 Copyright © April, 2015 – Cold War II Revision (Trump–Putin Summit) © August, 2018 Athens, Greece ISBN: 1496071468 ISBN-13: 978-1496071460 ii Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos © 2015 - 2018 This is dedicated to the remote exploration initiatives of the Stargate Project from the 1970s up until now, and to my family and friends who endured hard times to help make this book available. All images and items are copyright by their respective copyright owners and are displayed only for historical, analytical, scholarship, or review purposes. Any use by this report is done so in good faith and with respect to the “Fair Use” doctrine of U.S. Copyright law. The research, opinions, and views expressed herein are the personal viewpoints of the original writers. Portions and brief quotes of this book may be reproduced in connection with reviews and for personal, educational and public non-commercial use, but you must attribute the work to the source. You are not allowed to put self-printed copies of this document up for sale. Copyright © 2015 - 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Hitler’s Doubles The Cold War II Revision : Trump–Putin Summit [2018] is a reworked and updated account of the original 2015 “Hitler’s Doubles” with an improved Index. Ascertaining that Hitler made use of political decoys, the chronological order of this book shows how a Shadow Government of crisis actors and fake outcomes operated through the years following Hitler’s death –– until our time, together with pop culture memes such as “Wunderwaffe” climate change weapons, Brexit Britain, and Trump’s America. -

Ade Mark Inter-Partes Decision O/222/07

O-222-07 TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION Nos 2322346A & 2322346B BY ORDO TEMPLI ORIENTIS TO REGISTER TWO SERIES OF TWO TRADE MARKS OTO/ O T O & O.T.O. / O. T. O. IN CLASSES 9, 16 & 41 AND IN THE MATTER OF CONSOLIDATED OPPOSITIONS THERETO UNDER Nos.92269 & 92270 BY STARFIRE PUBLISHING LIMITED. BACKGROUND 1) On 31 January 2003, Ordo Templi Orientis of JAF Box 7666, New York 10116- 4632, United States of America applied under the Trade Marks Act 1994 for registration of a series of four trade marks, which, for administrative purposes, were split into two series of two trade marks as follows: Mark Number Class Specification OTO 2322346A 9 Printed publications in electronic readable O T O. form. 16 Printed matter; printed publications, By Consent No. books, stationery. E768739 and E2345700 41 Instruction, education and training services all relating to religion and religious matters. O.T.O. 2322346B 9 Printed publications in electronic readable O. T. O form. 16 Printed matter; printed publications, By Consent No. books, stationery. E768739 and E2345700. 41 Instruction, education and training services all relating to religion and religious matters. 2) On 26 January 2004 Starfire Publishing Limited of 9 Temple Fortune House, Finchley Road, London, NW11 6XH filed notice of opposition to the application. The grounds of opposition are in summary: a) The letters OTO/O.T.O. are an acronym derived from the initial letters of the name Ordo Templi Orientis (hereinafter OTO) which is the name of a spiritual fraternity which emerged from European freemasonry around 1905. -

Israel Regardie

This torrent represents a work of LOVE All texts so far gathered, as well as aU future gatherings aim at exposing interested students to occult information. Future releases will include submissions from users like YOU. For some of us, the time has come to mobilize. U you have an in terest in assisting in this process - we aUhave strengths to brin g to the table - please email occu lt .d igital.mobilizalion~gtt\O.il.com Complacency serves the old go ds. A GARDEN OF POM\EGRANATES AN OUTLINE OF THE QABALAH By the author: The Tree of Life My Rosicrucian Adventure The Art of True Healing ISRAEL REGARDIE The Middle Pillar The Philosopher's Stone The Golden Dawn Second Edition The Romance of Metaphysics Revised and Enlarged The Art and Meaning of Magic Be Yourself, the Art of Relaxation New Wings for Daedalus Twelve Steps to Spiritual Enlightenment The Legend of Aleister Crowley (with P.R. Stephensen) The Eye in the Triangle 1985 Llewellyn Publications St. Paul, Minnesota, 55164-0383, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION TO THE SECOND EDITION It is ironic that a period of the most tremendous technological advancement known to recorded history should also be labeled the Age of Anxiety. Reams have been written about modern man's frenzied search for his soul-and. indeed, his doubt that he even has one at a time when, like castles built on sand, so many of his cherished theories, long mistaken for verities, are crumbling about his bewildered brain. The age-old advice, "Know thyself," is more imperative than ever. -

Of UK Magick, Kenneth Grant, Has Made Ex

Trafficking with Elementals: Kenneth Grant and Arthur Machen Christopher Josiffe Kenneth Grant, born in 1924, is widely regarded as the ‘grand old man’ of British post-war occult scene. Grant is unique in that he is almost certainly the only person still alive to have known all three of the most influential figures in the twentieth century occult world, having had close personal relationships with both Aleister Crowley and Austin Osman Spare, and also having worked with Gerald Gardner, godfather of the modern Wiccan movement. It has long been acknowledged by students of the occult that Grant has made extensive use of the work of H.P. Lovecraft in his numerous writings and in his magical practices. It is perhaps less well-known that many elements from Arthur Machen’s fiction also features heavily in Grant’s work; in particular, The Novel of the Black Seal, The Hill of Dreams, and The White People. In 1944 Grant contacted Crowley with the intention of becoming his pupil; during these last three years of Crowley’s life Grant was also his secretary and personal assistant. The latter role included the supply of appropriate reading matter; in his fascinating and touching Crowley memoir, Remembering Aleister Crowleyi, Grant quotes a letter from Crowley in which the aged Beast writes: “Very many thanks for Secret Glory {Arthur Machen}; best of his I’ve read. Criticism when I’m strong enough.” (16 Jan 1945)ii. And later that year, at Crowley’s final home, the Hastings guest house Netherwood, they both experienced a vision of Pan, as Grant recounts: The Great God Pan: one morning at ‘Netherwood’, when Crowley accompanied me from the guest-house to the cottage, we experienced a joint ‘vision’ of a satyr-like form in the early spring sunshine. -

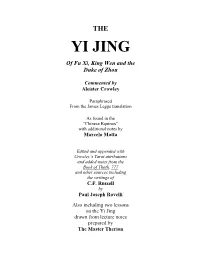

YI JING of Fu Xi, King Wen and the Duke of Zhou

THE YI JING Of Fu Xi, King Wen and the Duke of Zhou Commented by Aleister Crowley Paraphrased From the James Legge translation As found in the “Chinese Equinox” with additional notes by Marcelo Motta Edited and appended with Crowley‟s Tarot attributions and added notes from the Book of Thoth, 777 and other sources including the writings of C.F. Russell by Paul Joseph Rovelli Also including two lessons on the Yi Jing drawn from lecture notes prepared by The Master Therion A.‟.A.‟. Publication in Class B Imprimatur N. Frater A.‟.A.‟. All comments in Class C EDITORIAL NOTE By Marcelo Motta Our acquaintance with the Yi Jing dates from first finding it mentioned in Book Four Part III, the section on Divination, where A.C. expresses a clear preference for it over other systems as being more flexible, therefore more complete. We bought the Richard Wilhelm translation, with its shallow Jung introduction, but never liked it much. Eventually, on a visit to Mr. Germer, he showed us his James Legge edition, to which he had lovingly attached typewritten reproductions of A.C.‟s commentaries to the Hexagrams. We requested his permission to copy the commentaries. Presently we obtained the Legge edition and found that, although not as flamboyant as Wilhelm‟s, it somehow spoke more clearly to us. We carefully glued A.C.‟s notes to it, in faithful copy of our Instructor‟s device. To this day we have the book, whence we have transcribed the notes for the benefit of our readers. Mr. Germer always cast the Yi before making what he considered an important decision. -

Rua Augusta / Baixa Street Sounds Sofia

Episode 9. Mouth of Hell Location: Rua Augusta / Baixa Street sounds Sofia: You should now walk down Rua Augusta towards Terreiro do Paço. In 1929 Fernando Pessoa is reading the first volume of the Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Crowley was a notorious British magician and occultist. [00:00:29.09] Steffen Dix: He knew several famous figures. He was in contact with Aldous Huxley, with Albert Einstein. He prepared an exhibition in Berlin with some great German modernists, so Crowley was a very international figure. He lived between Berlin, London and Paris and travelled around the world, while Pessoa never left downtown Lisbon. And in this sense there couldn’t be a greater contrast than Crowley and Pessoa. Aleister Crowley voice recording Aleister Crowley: In the Years of the Primal Course, in the dawn of terrestrial birth, Man mastered the mammoth and horse, and Man was the Lord of the Earth. Sofia: The press dubbed Crowley "the wickedest man in the world". He identified himself as the “Antichrist” and he called himself "The Beast 666". On December 4th, 1929 Fernando Pessoa wrote to Crowley's publisher, Mandrake Press. It was to correct a mistake in the magician's astrological chart. Street sounds Steffen Dix: And he asked if the publisher could tell Crowley and the publisher did so. Then Crowley got in touch, maybe he found some interest in Pessoa and he was fairly quick to state that he was coming to Portugal. Sofia: This started a correspondence that led to a meeting between Pessoa and Crowley on September 2nd, 1930, in Lisbon. -

Download Art of Domination, Anna Riva, Mandrake Press, Limited, 1995

Art of Domination, Anna Riva, Mandrake Press, Limited, 1995, 0943832233, 9780943832234, . DOWNLOAD http://archbd.net/1i2RATV The Book of Spells , Kuriakos , Kuriakos, Jul 2, 2008, , 56 pages. This book will show you how to do Magick Spells anytime and anywhere by using these 'words of power'. Words of power are powerful ancient words used to bring about Magickal .... Voodoo Dolls in Magick and Ritual , Denise Alvarado, Apr 1, 2009, , 212 pages. For the first time anywhere, explore the history, mystery, and magick of Voodoo Dolls in this fascinating new book. Tracing the Voodoo doll's roots back in history, author .... Slavery in the Spanish Philippines , William Henry Scott, 1991, Social Science, 78 pages. Casting Spells , Barbara Bretton, Nov 4, 2008, Fiction, 320 pages. Magic. Knitting. Love. A new series and a delightful departure by the USA Today bestselling author of Just Desserts. Sugar Maple looks like any Vermont town, but it?s inhabited .... Wicca Candle Magick , Gerina Dunwich, 1996, Body, Mind & Spirit, 194 pages. Reveals the mystical powers of the candle through such topics as candle crafting, consecration, symbolism of colors, and various candle magick rituals.. Secrets of Magical Seals , Anna Riva, Jun 1, 1975, , 64 pages. Candlelight Spells The Modern Witch's Book of Spellcasting, Feasting, and Healing, Gerina Dunwich, 1988, Body, Mind & Spirit, 186 pages. Briefly discusses the history of witchcraft, provides recipes for foods, herbs, and spells, and defines witchcraft terms. God's Prayer Book The Power and Pleasure of Praying the Psalms, Ben Patterson, 2008, Religion, 312 pages. The psalms often stretch and perplex readers as they teach, but they also open a divine window on prayer. -

Charles Stansfeld Jones

1 Charles Stansfeld Jones CHARLES STANSFELD JONESi por Frater Keron-ε Faze o que tu queres deverá ser o todo da Lei. Charles R. John Stansfeld Jones (Frater O.I.V.V.I.O.) é considerado o filho mágico da Besta 666. Foi ele quem descobriu a chave para O Livro da Lei, como profetizado no mesmo. Juntou-se a A∴A∴ em 1912 e.v. sob o mote U.I.O.O.I.U. (Unus in Omnibus, Omnia in Uno), sob instrução de Frater Per Ardua (J. F. C. Fuller). Em 26 de Fevereiro de 1913 e.v. recebe uma carta do Cancellarius da Ordem, passando-o a Neófito, sob o seu mais famoso mote, Achad (Um, unidade). Juntando-se a Ordo Templi Orientis (organização maçônica espúria chefiada por Crowley) inicia um processo de expansão pela América e Canadá, através da Loja em Vancouver, sendo patenteado no IX° por Theodor Reuss. Em 21 de Junho de 1916 e.v. (no Solstício), Jones realiza o juramento do grau 8º=3□ e se torna um Bebê do Abismo. Menos de um mês depois, escreve um telegrama para Crowley sobre o feito, e o mesmo demorou a Espaço Novo Æon www.thelema.com.br 2 Keron-ε compreender o ocorrido: “Após ele (Crowley) averiguar que eu pulei no Abismo em seu favor para que pudesse assumir o grau de Magus que clamava ter atingido, escreveu pra mim, ‘Ainda estou in profundis’”. Para ele foi um ato sem precedente na história da magia. Estava além de sua imaginação conceber tal evento, pois jamais um homem, em tão pouco tempo, tornara-se um Magister Templi1.