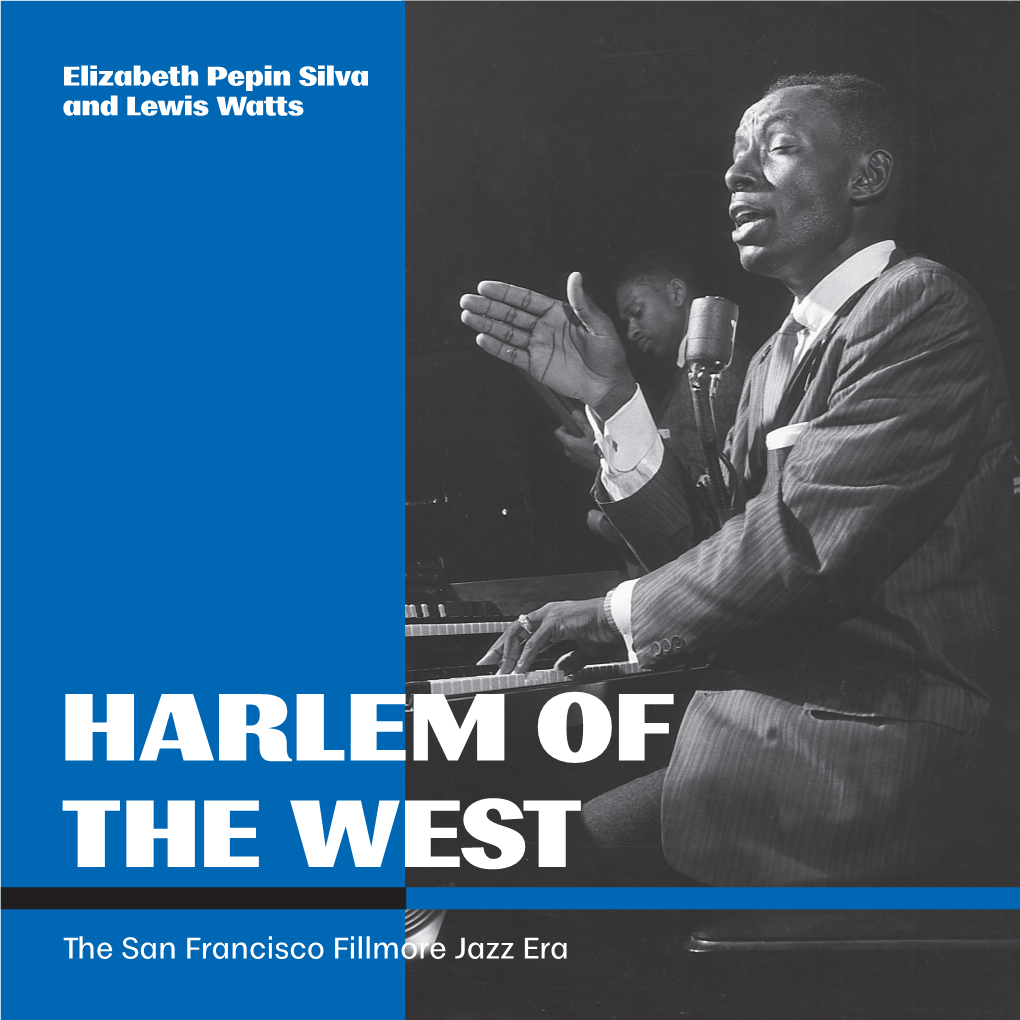

Harlem of the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Dee Bell Long

Biography Discography: Concord Jazz recordings: Let There Be Love with Stan Getz and Eddie Duran One by One with Tom Harrell and Eddie Duran Laser Records recordings Sagacious Grace: with Houston Person, Al Plank, John Stowell, and Michael Spiro Silva • Bell • Elation with Marcos Silva, Andy Narell and Barry Finnerty Commendation: Downbeat Magazine voted Dee, “Talent Deserving Wider Recognition for Female Vocals” for both Concord albums. BAM Magazine nominated Let There Be Love as the Best Debut Album and One by One as Best Jazz Vocal Album, both in their release years. Let There Be Love was a Billboard pick and won the Bay Area Golden Globe award. Dee’s rendition of the title track was chosen by Palo Alto records own Dr. Herb Wong as the signature interpretation of Let There Be Love for the 1988 Hal Leonard Ultimate Jazz Fakebook. All three of Dee’s albums have been in the top of the airplay charts for long runs with Let There Be Love and One by One reaching thirteen and nineteen respectively, Dee and the “historic release” Sagacious Grace at thirty-one. Bell Silva • Bell • Elation biographical liner notes by Jazz Author James Gavin: “Who’s Dee Bell?” wondered many jazz fans in 1983, when that name appeared above RECORD COMPANY those of Stan Getz and an esteemed veteran guitarist, Eddie Duran, on the cover of a Concord Laser Records, LLC Jazz LP, Let There Be Love. Like a jazz Cinderella, this gifted unknown singer – a former hippie and waitress in northern California – had been discovered by Getz and Duran, both of whom 5457 Monroe Road volunteered to play on her debut LP. -

THE BRILL BUILDING, 1619 Broadway (Aka 1613-23 Broadway, 207-213 West 49Th Street), Manhattan Built 1930-31; Architect, Victor A

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 23, 2010, Designation List 427 LP-2387 THE BRILL BUILDING, 1619 Broadway (aka 1613-23 Broadway, 207-213 West 49th Street), Manhattan Built 1930-31; architect, Victor A. Bark, Jr. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1021, Lot 19 On October 27, 2009 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Brill Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark site. The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Three people spoke in support of designation, including representatives of the owner, New York State Assembly Member Richard N. Gottfried, and the Historic Districts Council. There were no speakers in opposition to designation.1 Summary Since its construction in 1930-31, the 11-story Brill Building has been synonymous with American music – from the last days of Tin Pan Alley to the emergence of rock and roll. Occupying the northwest corner of Broadway and West 49th Street, it was commissioned by real estate developer Abraham Lefcourt who briefly planned to erect the world’s tallest structure on the site, which was leased from the Brill Brothers, owners of a men’s clothing store. When Lefcourt failed to meet the terms of their agreement, the Brills foreclosed on the property and the name of the nearly-complete structure was changed from the Alan E. Lefcourt Building to the, arguably more melodious sounding, Brill Building. Designed in the Art Deco style by architect Victor A. Bark, Jr., the white brick elevations feature handsome terra-cotta reliefs, as well as two niches that prominently display stone and brass portrait busts that most likely portray the developer’s son, Alan, who died as the building was being planned. -

Drums • Bobby Bradford - Trumpet • James Newton - Flute • David Murray - Tenor Sax • Roberto Miranda - Bass

1975 May 17 - Stanley Crouch Black Music Infinity Outdoors, afternoon, color snapshots. • Stanley Crouch - drums • Bobby Bradford - trumpet • James Newton - flute • David Murray - tenor sax • Roberto Miranda - bass June or July - John Carter Ensemble at Rudolph's Fine Arts Center (owner Rudolph Porter)Rudolph's Fine Art Center, 3320 West 50th Street (50th at Crenshaw) • John Carter — soprano sax & clarinet • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums 1976 June 1 - John Fahey at The Lighthouse December 15 - WARNE MARSH PHOTO Shoot in his studio (a detached garage converted to a music studio) 1490 N. Mar Vista, Pasadena CA afternoon December 23 - Dexter Gordon at The Lighthouse 1976 June 21 – John Carter Ensemble at the Speakeasy, Santa Monica Blvd (just west of LaCienega) (first jazz photos with my new Fujica ST701 SLR camera) • John Carter — clarinet & soprano sax • Roberto Miranda — bass • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums • Melba Joyce — vocals (Bobby Bradford's first wife) June 26 - Art Ensemble of Chicago Studio Z, on Slauson in South Central L.A. (in those days we called the area Watts) 2nd-floor artists studio. AEC + John Carter, clarinet sat in (I recorded this on cassette) Rassul Siddik, trumpet June 24 - AEC played 3 nights June 24-26 artist David Hammond's Studio Z shots of visitors (didn't play) Bobby Bradford, Tylon Barea (drummer, graphic artist), Rudolph Porter July 2 - Frank Lowe Quartet Century City Playhouse. • Frank Lowe — tenor sax • Butch Morris - drums; bass? • James Newton — cornet, violin; • Tylon Barea -- flute, sitting in (guest) July 7 - John Lee Hooker Calif State University Fullerton • w/Ron Thompson, guitar August 7 - James Newton Quartet w/guest John Carter Century City Playhouse September 5 - opening show at The Little Big Horn, 34 N. -

From King Records Month 2018

King Records Month 2018 = Unedited Tweets from Zero to 180 Aug. 3, 2018 Zero to 180 is honored to be part of this year's celebration of 75 Years of King Records in Cincinnati and will once again be tweeting fun facts and little known stories about King Records throughout King Records Month in September. Zero to 180 would like to kick off things early with a tribute to King session drummer Philip Paul (who you've heard on Freddy King's "Hideaway") that is PACKED with streaming audio links, images of 45s & LPs from around the world, auction prices, Billboard chart listings and tons of cool history culled from all the important music historians who have written about King Records: “Philip Paul: The Pulse of King” https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=32149 Aug. 22, 2018 King Records Month is just around the corner - get ready! Zero to 180 will be posting a new King history piece every 3 days during September as well as October. There will also be tweeting lots of cool King trivia on behalf of Xavier University's 'King Studios' historic preservation collaborative - a music history explosion that continues with this baseball-themed celebration of a novelty hit that dominated the year 1951: LINK to “Chew Tobacco Rag” Done R&B (by Lucky Millinder Orchestra) https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=27158 Aug. 24, 2018 King Records helped pioneer the practice of producing R&B versions of country hits and vice versa - "Chew Tobacco Rag" (1951) and "Why Don't You Haul Off and Love Me" (1949) being two examples of such 'crossover' marketing. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Biography Dee Bell

Biography Discography: Concord Jazz recordings: Let There Be Love with Stan Getz and Eddie Duran One by One with Tom Harrell and Eddie Duran Laser Records recordings Sagacious Grace: with Houston Person, Al Plank, John Stowell, and Michael Spiro Silva • Bell • Elation with Marcos Silva, Andy Narell and Barry Finnerty Commendation: Downbeat Magazine voted Dee, “Talent Deserving Wider Recognition for Female Vocals” for both Concord albums. BAM Magazine nominated Let There Be Love as the Best Debut Album and One by One as Best Jazz Vocal Album, both in their release years. Let There Be Love was a Billboard pick and won the Bay Area Golden Globe award. Dee’s rendition of the title track was chosen by Palo Alto records own Dr. Herb Wong as the signature interpretation of Let There Be Love for the 1988 Hal Leonard Ultimate Jazz Fakebook. All three of Dee’s albums have been in the top of the airplay charts for long runs with Let There Be Love and One by One reaching thirteen and nineteen respectively, Dee and the “historic release” Sagacious Grace at thirty-one. Bell Silva • Bell • Elation biographical liner notes • jazz author James Gavin: “Who’s Dee Bell?” wondered many jazz fans in 1983, when that name appeared above RECORD COMPANY those of Stan Getz and an esteemed veteran guitarist, Eddie Duran, on the cover of a Concord Laser Records, LLC Jazz LP, Let There Be Love. Like a jazz Cinderella, this gifted unknown singer – a former hippie and waitress in northern California – had been discovered by Getz and Duran, both of whom 5457 Monroe Road volunteered to play on her debut LP. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

Dee Bell Silver Bells Was the Bell Family Signature Christmas Song

Why Silva • Bell • Elation? • Dee Bell Silver Bells was the Bell Family signature Christmas song. It was a tradition in our family holiday jam sessions. Because of this, the merging of the two names Marcos Silva and Dee Bell seemed tunefully obvious. Elation was the result of the Silva Bell musical partnership. From the first recording with Stan Getz to the present, the rhythms and music of Brazil have infused new tonal colors and energy into the music that enlivens my spirit. Stan and Eddie Duran introduced me to those rhythms and prompted deeper exploration into the music of Antonio Carlos Jobim, Ivan Lins, Maria Bethania, Simone, Dori and Nana Caymmi, Joyce, Toninho Horta, Chico Buarque, Djavan, Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Elis Regina to mention a few. Maria Marquez, a contemporary of mine also living and performing in San Francisco in the 80s, generously made a tape for me of these artists and several others that further inspired. Bless you Maria! This music has sustained my spirit through the last thirty years of life’s crushing waves and lean times. The first two Concord recordings Let There Be Love and One by One were successfully acclaimed, then the waves began to hit. By the time the third recording, Sagacious Grace, was Dee finally revived from certain death by recording engineers Bud Spangler and Dan Feizli, the Bell heart of the recording and my musical director, Al Plank, had, to quote James Gavin in Silva • Bell • Elation’s liner notes, “moved on to the next world.” The dilemma of how to present a RECORD COMPANY CD release show without the master musician left me stymied. -

LINER NOTES Print

LONG NOTES GEORGE WINSTON LINUS AND LUCY – THE MUSIC OF VINCE GUARALDI – VOL. 1: George Winston on Vince Guaraldi (Vince’s name is pronounced “Gurr-al-dee”, beginning with a hard “G) “Vince Guaraldi once said that he wanted to write standards, not just hits, and that he did,” says George Winston. “His music is very much a part of the fabric of American culture, but not many people know the man behind the music, and it is unusual for someone’s music to be better known than their name (some other composers who have also been in this situation are Allen Toussaint, Randy Newman (in the early and mid 1960s), Joni Mitchell (in the mid 1960s), Leonard Cohen (in the mid-1960s), Laura Nyro, Percy Mayfield, Otis Blackwell, and Wendy Waldman). If I play Linus & Lucy and other Vince Guaraldi Peanuts pieces for most kids they will usually say right away, ‘That’s Charlie Brown music’. Vince’s soundtracks for the first 16 of the Peanuts animations from the 1960s & 1970s continue to delight millions of people around the world, and many of his albums remain in print. I like to help make the connection for people that Vince Guaraldi was a great jazz pianist, and that he was the composer of the soundtracks for the first 16 of the Peanuts animation, as well as of many other great jazz pieces. Vince’s best known standards are Cast Your Fate to the Wind, Linus and Lucy, Christmas Time is Here, as well as Skating, and Christmas is Coming. A lot of Vince’s music is seasonal, and it reminds me very much of my upbringing in Montana. -

The Bebop Revolution in Jazz by Satyajit Roychaudhury

The Bebop Revolution in Jazz by Satyajit Roychaudhury The bebop style of jazz is a pivotal invention in twentieth-century American popular music - an outgrowth of the rhythmic and harmonic experiments of young African-American jazz musicians. At first a source of controversy because of its unorthodox approach, bebop eventually gained widespread acceptance as the foundation of "modern" jazz, and it continues to influence jazz musicians. The process of its creation was solidly grounded in New York City. Because of its emphasis on improvisation, jazz has maintained a strong tradition of creative invention throughout its history. This tradition has encouraged jazz musicians to cultivate new musical ideas, based on innovative uses of harmony, rhythm, timbre and instrumentation. Jazz has thus encompassed a continually evolving diversity of individual and collective styles over the past century. The emphasis on improvisation has made live performance a crucial element of the innovation process. During the 1st half of the 20th century the available technology limited the length of the improvisations and live performance served as the primary showcase for jazz musicians' talents. Because performance opportunities for the most talented musicians were concentrated in the entertainment districts of major cities, the creation of new jazz styles became strongly associated with places, such as New Orleans, Chicago, Kansas City, and New York City. Bebop emerged during the 1940s as a reaction “Swing” and as an expression of artistic innovation within a community of younger African-American jazz musicians. Certain jazz clubs in Harlem provided a setting for experimentation that culminated in the bebop style. The style's subsequent popularization occurred in jazz clubs in midtown Manhattan, at first along 52nd Street and later on nearby sections of Broadway. -

Jan. 24, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield & Nick Gravenites

Jan. 24, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield & Nick Gravenites – 750 Vallejo In North Beach, SF “The Jam” Mike Bloomfield and friends at Fillmore West - January 30-31-Feb. 1-2, 1970? Feb. 11, 1970 -- Fillmore West -- Benefit for Magic Sam featuring: Butterfield Blues Band / Mike Bloomfield & Friends / Elvin Bishop Group / Charlie Musselwhite / Nick Gravenites Feb. 28, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield, Keystone Korner, SF March 19, 1970 – Elvin Bishop Group plays Keystone Korner , SF Bloomfield was supposed to show for a jam. Did he? March 27,28, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield and Nick Gravenites, Keystone Korner ***** MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD AND FRIENDS 1970. Feb. 27. Eagles Auditorium, Seattle 1. “Wine” (8.00) This is the encore from Seattle added on the bootleg as a “filler”! The rest is from Long Beach Auditorium Apr. 8, 1971. 1970 1 – CDR “JAMES COTTON W/MIKE BLOOMFIELD AND FRIENDS” Bootleg 578 ***** JANIS JOPLIN AND THE BUTTERFIELD BLUES BAND 1970. Mar. 28. Columbia Studio D, Hollywood, CA Janis Joplin, vocals - Paul Butterfield, hca - Mike Bloomfield, guitar - Mark Naftalin, organ - Rod Hicks, bass - George Davidson, drums - Gene Dinwiddle, soprano sax, tenor sax - Trevor Lawrence, baritone sax - Steve Madaio, trumpet 1. “One Night Stand” (Version 1) (3.01) 2. “One Night Stand” (Version 2) wrong speed 1982 1 – LP “FAREWELL SONG” CBS 32793 (NL) 1992 1 – CD “FAREWELL SONG” COLUMBIA 484458 2 (US) ?? 2 – CD-3 BOX SET CBS ***** SAM LAY 1970 Producer Nick Gravenites (and Michael Bloomfield) Sam Lay, dr, vocals - Michael Bloomfield, guitar - Bob Jones, dr – bass ? – hca ? – piano ? – organ ? Probably all of The Butterfield Blues Band is playing. Mark Naftalin, Barry Goldberg, Paul Butterfield 1.