Chapter 4 Willeen Keough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expressions of Sovereignty: Law and Authority in the Making of the Overseas British Empire, 1576-1640

EXPRESSIONS OF SOVEREIGNTY EXPRESSIONS OF SOVEREIGNTY: LAW AND AUTHORITY IN THE MAKING OF THE OVERSEAS BRITISH EMPIRE, 1576-1640 By KENNETH RICHARD MACMILLAN, M.A. A Thesis . Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University ©Copyright by Kenneth Richard MacMillan, December 2001 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2001) McMaster University (History) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Expressions of Sovereignty: Law and Authority in the Making of the Overseas British Empire, 1576-1640 AUTHOR: Kenneth Richard MacMillan, B.A. (Hons) (Nipissing University) M.A. (Queen's University) SUPERVISOR: Professor J.D. Alsop NUMBER OF PAGES: xi, 332 11 ABSTRACT .~. ~ This thesis contributes to the body of literature that investigates the making of the British empire, circa 1576-1640. It argues that the crown was fundamentally involved in the establishment of sovereignty in overseas territories because of the contemporary concepts of empire, sovereignty, the royal prerogative, and intemationallaw. According to these precepts, Christian European rulers had absolute jurisdiction within their own territorial boundaries (internal sovereignty), and had certain obligations when it carne to their relations with other sovereign states (external sovereignty). The crown undertook these responsibilities through various "expressions of sovereignty". It employed writers who were knowledgeable in international law and European overseas activities, and used these interpretations to issue letters patent that demonstrated both continued royal authority over these territories and a desire to employ legal codes that would likely be approved by the international community. The crown also insisted on the erection of fortifications and approved of the publication of semiotically charged maps, each of which served the function of showing that the English had possession and effective control over the lands claimed in North and South America, the North Atlantic, and the East and West Indies. -

Thms Summary for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

THMs Summary for Public Water Supplies Water Resources Management Division in Newfoundland and Labrador Community Name Serviced Area Source Name THMs Average Average Total Samples Last Sample (μg/L) Type Collected Date Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook 154.13 Running 72 Feb 25, 2020 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The 68.30 Running 74 Feb 03, 2020 Outflow) Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond 326.50 Running 52 Feb 05, 2020 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 142.25 Running 106 Feb 27, 2020 Intakes) Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond 197.00 Running 51 Feb 18, 2020 Badger Badger Well Field, 2 wells on 5.20 Simple 21 Sep 27, 2018 standby Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond 108.53 Running 25 Feb 12, 2020 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond 0.00 Simple 9 Dec 13, 2018 Barachois Brook Barachois Brook Drilled 0.00 Simple 8 Jun 21, 2019 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as 0.35 Simple 2 Jan 18, 2012 Castors River North) Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well 94.80 Running 48 Mar 10, 2020 Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond 117.83 Running 68 Mar 03, 2020 Bay Roberts Bay Roberts, Rocky Pond 38.68 Running 83 Feb 11, 2020 Spaniard's Bay Bay St. George South Heatherton #1 Well Heatherton 8.35 Simple 7 Dec 03, 2013 (Home Hardware) Bay St. George South Jeffrey's #1 Well Jeffery's (Joe 0.00 Simple 5 Dec 03, 2013 Curnew) Bay St. George South Robinson's #1 Well Robinson's 3.30 Simple 4 Dec 03, 2013 (Louie MacDonald) Bay St. -

Héros D'autrefois, Jacques Cartier Et Samuel De Champlain

/ . A. 4*.- ? L I B RAR.Y OF THE U N IVER.SITY Of ILLINOIS B C327d Ill.Hist.aurv g/acques wartJer et Ôan\uel ae wi\an\plait> OUVRAGE DU MEME AUTEUR Parlons français : Petit traité de prononciation Prix, cartonné 50 sous. J\éros a autrejoiOIS acques wartier et Samuef è» ©&an\plcun JOSEPH DUMÂIS fondateur du j|ouYenir patriotique AVEC UNE PRÉFACE DE J.-A. DE PLAINES QUÉBEC Imprimerie de I'Action Sociale Limitée 1913 PRÉFACE âgé Monsieur le professeur Joseph Dumais, déjà avanta- geusement connu au Canada français et en Acadie, par ^ ses cours de diction française et par ses conférences pa- triotiques sur notre histoire, ne pouvait mieux commencer la série des publications du « Souvenir patriotique )) — une société qu'il a fondée et dont le beau nom dit le but excellent, — que par l'histoire, populaire et néanmoins assez riche d'érudition, des deux premiers héros de notre grande histoire. Il convenait, en effet, que le début de cette série fut consacré aux commencements mêmes de notre histoire, d'autant que ces commencements sont d'un intérêt tou- jours empoignant pour nous, et d'une grandeur de con- ception digne de toute admiration. La grandeur de l'histoire, comme d'ailleurs son intérêt, ne dépend pas en effet principalement des masses d'hom- mes qu'elle peut faire mouvoir dans le récit d'événements ordinaires, elle dépend plutôt de la grandeur morale des héros qu'elle met en mouvement, sous l'impulsion d'un puissant idéal, pour la réalisation d'une œuvre d'autant plus élevée et plus glorieuse qu'elle est plus ardue et plus périlleuse. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload Updated December 17, 2019 Serviced Out Of City Prov Routing City Carrier Name ABRAHAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADEYTON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS BEACH NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ALLANS ISLAND NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AMHERST COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANCHOR POINT NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANGELS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point APPLETON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AQUAFORTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARGENTIA NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARNOLDS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEN COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEY BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AVONDALE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACON COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGER NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGERS QUAY NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAIE VERTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAINE HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAKERS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARACHOIS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARENEED NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D ISLANDS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARTLETTS HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE EAST NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY BULLS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY DE VERDE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY L'ARGENT NL TORONTO, ON -

A Strategy for Early Childhood Development in the Northeast Avalon Strategic Social Plan Region

A Strategy for Early Childhood Development in the Northeast Avalon Strategic Social Plan Region Final Report: October 18, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 SECTION ONE: BACKGROUND INFORMATION 12 The Strategic Social Plan 12 Northeast Avalon Region 14 Northeast Avalon Region Steering Committee Representatives 15 Guiding Principles 15 SECTION TWO: FOCUS ON EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT 17 Defining “Early Childhood Development” 17 Who is Involved in Early Childhood Development? 17 Early Childhood Development Advisory Committee 19 Links to Other Initiatives 19 SECTION THREE: LITERATURE REVIEW AND QUALITATIVE INFORMATION Literature Review 20 Key Themes 20 Qualitative Information 21 Key Themes 21 SECTION FOUR: VISION, VALUES, GUIDING PRINCIPLES 26 SECTION FIVE: GOALS, OBJECTIVES, INDICATORS 27 2 SECTION SIX: ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN 34 Population Profile 36 Goal #1: Objective #1.1 38 6.1 Family Structure 39 6.2 Median Lone Parent Family Income 47 6.3 Children in Social Assistance Households 53 6.4 Self-reliance Ratio 63 6.5 Employment Rate 67 6.6 Level of Education 77 Goal #1: Objective #1.2 85 6.7 Motor and Social Development 86 6.8 School Readiness 87 6.9 Separation Anxiety 88 6.10 Emotional Disorder-Anxiety Scale 89 6.11 Physical Aggression and Opposition 90 6.12 Prosocial Behaviour Score 91 Goal #1: Objective #1.3 92 SECTION SEVEN: NEXT STEPS - ACTION PLANNING 93 BIBLIOGRAPHY 94 APPENDIX A: ORGANIZATIONS CONSULTED 99 APPENDIX B: NEIGHBOURHOOD BOUNDARIES 100 APPENDIX C: NEIGHBOURHOOD LEVEL DATA 117 APPENDIX D: NEIGHBOURHOOD SUMMARY CHARTS 150 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Northeast Avalon Region Steering Committee of the Strategic Social Plan gratefully acknowledges the commitment and expertise of numerous groups and individuals in developing this comprehensive strategy. -

Student Handbook

Students Against Drinking & Driving (S.A.D.D.) Newfoundland & Labrador Student Handbook I N D E X SECTION 1: CHAPTER EXECUTIVE INFORMATION (WHITE PAGES) 1. EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS .............................................................................. 1 A) Election ................................................................................................... 1 B) Roles - President ..................................................................................... 2 - Vice-President ............................................................................. 3 - Vice-President of Finance ........................................................... 3 - Vice-President of Public Relations ............................................. 4 - Secretary ..................................................................................... 5 - Junior Rep .................................................................................. 6 - Teacher / Advisors ...................................................................... 7 C) Planning a Chapter Meeting .................................................................... 8 Sample Meeting Agenda .................................................................... 10 D) How to Write Minutes ............................................................................. 11 Sample Minutes Sheet ........................................................................ 12 Sample Monthly Report ..................................................................... 13 2. HOW TO PLAN A PROVINCIAL -

RMHCNL Annual Report 2019

Weelo (Age 1) from St.Pierre et Miquleon. 1 stay, 501 nights. RONALD MCDONALD HOUSE CHARITIES® Newfoundland & Labrador Newfoundland & Labrador 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Natalia Williams (Age 6) Emma Clarke (Age 6) from Labrador City, NL. from Victoria, NL. 4 stays, 380 nights. 24 stays, 314 nights. Keeping families close TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION • MISSION • VALUES 4 Message from Board Chair & Executive Director 5 Board of Directors/Committees 6 FAMILY SUPPORT PROGRAMS 7 OUR IMPACT 2019 8 PULLING TOGETHER FOR FAMILIES 9 The Dedicated Volunteers 10 Strength in Numbers Volunteer Gathering 11 Helping Hand Awards 12 Adopt-a-Room Program 13 Community Events 14 McDonald’s: Our Founding and Forever Partner 15 Miss Achievement 16 OUR SIGNATURE EVENTS 17 Spare Some Love Bowling Event 18 “Fore” the Families Golf Classic 19 Red Shoe Crew – Walk for Families 20 Team RMHC 22 Sock It For Sick Kids & Their Families 23 Lights of Love Season of Giving Campaign 24 THANK YOU FROM OUR FAMILY TO YOURS 25 Donor Recognition 26 Seventh Birthday Celebration 28 MESSAGE FROM TREASURER 29 Financial Report 30 Vision Positively impact the health and lives of sick children, their families and their communities. Mission Ronald McDonald House Charities® Newfoundland and Labrador provides sick children and their families with a comfortable home where they can stay together in an atmosphere of caring, compassion and support close to the medical care and resources they need. Values Caring • Inclusion • Inspiration • Quality • Teamwork • Trust and Integrity MEET WEELO Generally, all mothers experiencing a high-risk pregnancy in Saint Pierre et Miquelon, a piece of French territory off the coast of Newfoundland, are referred to St. -

'A Large House on the Downs': Household Archaeology

‘A LARGE HOUSE ON THE DOWNS’: HOUSEHOLD ARCHAEOLOGY AND MIDDLE-CLASS GENTILITY IN EARLY 19TH-CENTURY FERRYLAND, NEWFOUNDLAND by © Duncan Williams A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland February 2019 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador ii ABSTRACT This thesis uses a household-based archaeological approach to examine changing settlement patterns and lifeways associated with a period of crucial change on Newfoundland’s southern Avalon Peninsula – namely the first half of the 19th century. The period witnessed a significant increase in permanent residents (including a large influx of Irish Catholic immigrants), the downfall of the migratory fishery (and resulting shift to a family-based resident fishery), and radical political/governmental changes associated with increased colonial autonomy. As part of these developments, a new middle class emerged composed mainly of prosperous fishermen and individuals involved in local government. A micro-historical approach is used to analyze a single household assemblage in Ferryland, thus shedding light on the development of a resident ‘outport gentry’ and changing use of the landscape in this important rural centre. Though likely initially built by a member of Ferryland’s elite (Vice-Admiralty Judge William Carter), the major occupation of the structure, as seen archaeologically, appears to be represented by the tenancies of two upper middle-class families. Comparative analysis places this household and its social landscape in the broader community of Ferryland, as well as emergent upper middle-class society in North America. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes much to many individuals and organizations, and it will be difficult to properly acknowledge them all in the space of a couple pages. -

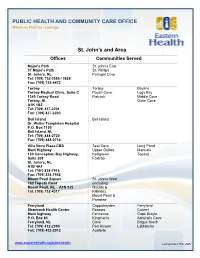

St. John's and Area

PUBLIC HEALTH AND COMMUNITY CARE OFFICE Where to Find Us - Listings St. John’s and Area Offices Communities Served Major’s Path St. John’s East 37 Major’s Path St. Phillips St. John’s, NL Portugal Cove Tel: (709) 752-3585 / 3626 Fax: (709) 752-4472 Torbay Torbay Bauline Torbay Medical Clinic, Suite C Pouch Cove Logy Bay 1345 Torbay Road Flatrock Middle Cove Torbay, NL Outer Cove A1K 1B2 Tel: (709) 437-2201 Fax: (709) 437-2203 Bell Island Bell Island Dr. Walter Templeton Hospital P.O. Box 1150 Bell Island, NL Tel: (709) 488-2720 Fax: (709) 488-2714 Villa Nova Plaza-CBS Seal Cove Long Pond Main Highway Upper Gullies Manuels 130 Conception Bay Highway, Kelligrews Topsail Suite 208 Foxtrap St. John’s, NL A1B 4A4 Tel: (70(0 834-7916 Fax: (709) 834-7948 Mount Pearl Square St. John’s West 760 Topsail Road (including Mount Pearl, NL A1N 3J5 Goulds & Tel: (709) 752-4317 Kilbride), Mount Pearl & Paradise Ferryland Cappahayden Ferryland Shamrock Health Center Renews Calvert Main highway Fermeuse Cape Broyle P.O. Box 84 Kingman’s Admiral’s Cove Ferryland, NL Cove Brigus South Tel: (709) 432-2390 Port Kirwan LaManche Fax: (709) 432-2012 Auaforte www.easternhealth.ca/publichealth Last updated: Feb. 2020 Witless Bay Main Highway Witless Bay Burnt Cove P.O. Box 310 Bay Bulls City limits of St. John’s Witless Bay, NL Bauline to Tel: (709) 334-3941 Mobile Lamanche boundary Fax: (709) 334-3940 Tors Cove but not including St. Michael’s Lamanche. Trepassey Trepassey Peter’s River Biscay Bay Portugal Cove South St. -

School Development Report

Holy Family Elementary School 2016-2017 Annual School Development Report P.O. Box 130 50B Main Road, Chapel Arm Newfoundland and Labrador A0B 1L0 “Here Everyone Respects Others” Annual School Development Report Page 1 Annual School Development Report Page 2 A Message from Susan George Principal of Holy Family School The Annual School Development Report for 2016-2017 highlights the school year for Holy Family Elementary. This document contains information about our academic successes and challenges as well as information about the many projects and events in which we have participated as part of our school’s Academic and Safe and Caring goals. Our school and students cannot reach their full potential without the support of parents, families, School Council and the surrounding communities. As always, I am proud of the support of everyone in our school family and for that I say thank you! Each school year we continue to seek new ways to grow and improve our school and to help our students reach their full potential academically and socially. We are continually working to ensure our school is a safe and happy place for our young learners, our staff and our visitors. Environmental initiatives with our Green Team, STEM projects, music and drama programs along with regular strong support for academics are just some of the ways we help our students. Please take the time to read this report. Ask questions, volunteer at school, get involved with your child’s learning – show your child that you value their education, their teachers and their place -

286 Thursday, December 10Th, 2020 the House Met at 1:30 O'clock In

286 Thursday, December 10th, 2020 The House met at 1:30 o’clock in the afternoon pursuant to adjournment. The Member for Mount Pearl – Southlands (Mr. Lane) made a Statement to recognize nominees and recipients of the Best of Mount Pearl Awards 2020. The Member for Conception Bay East – Bell Island (Mr. Brazil) made a Statement to recognize Rachel Moss of Portugal Cove – St. Phillips for her volunteer work in many capacities. The Member for St. Barbe – L’Anse aux Meadows (Mr. Mitchelmore) made a Statement to recognize Port au Choix’s oldest resident, Ms. Yvonne Ploughman (nee Gould) who celebrated her 100th Birthday on December 8th, 2020. The Member for Ferryland (Mr. O’Driscoll) made a Statement to recognize Clarence and Anne Molloy of Portugal Cove South, owners of Molloy’s Transportation and Courier Service, which was in business for 52 years when they retired March 31st, 2020. The Member for Bonavista (Mr. Pardy) made a Statement to recognize Jevon Marsh of Bonavista on being selected as a 2021 Rhodes Scholar. The Honourable the Minister of Immigration, Skills and Labour (Mr. Byrne) made a Statement to recognize Avalon Employment Incorporated on earning the United Nations International 2021 Zero Project Award. The Honourable the Minister of Health and Community Services (Mr. Haggie) made a Statement to congratulate Niki Legge, the Department’s Director of Mental Health and Addictions, on receiving the International eMental Health Innovation Leadership Award from the eMental Health International Collaborative. The Honourable the Minister of Education (Mr. Osborne) made a Statement to congratulate Jevon Marsh of Bonavista who was recently named to the Rhodes Scholars- elect class of 2021.