Computational Dialectology in Irish Gaelic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ulster Final Programme

CLUICHE CEANNAIS ULADH2O2O AN CABHÁN DÚN NAVERSUS NGALL 22Ú SAMHAIN 2020 IT’S ON PÁIRC LÚTHCHLEASÍOCHTA ARD MHACHA 4:00PM £5/€5 RÚNAI: ULSTER.GAA.IE The stands may be silent but TODAY’S GAME we know our communities are CLUICHE AN LAE INNIU standing tall behind us. Help us make your SuperFan voice heard by sharing a video of how you Support Where You’re From on: @supervalu_irl @SuperValuIreland using the #SuperValuSuperFans SUPPORT 72 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O Where You’re From TODAY’S GAME CLUICHE AN LAE INNIU (SUBJECT TO WINNER ON THE DAY) @ ATHLETICVERSUS GROUNDS, ARMAGH SUNDAY 22ND NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Final (4:00pm) Réiteoir: Barry Cassidy (Doire) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Ciaran Branagan (An Dún) Maor Líne: Jerome Henry (Maigh Eo) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Sean Laverty (Aontroim) Maoir: Kevin Toner, Alan Nash, Tom O’Kane & Marty Donnelly CLÁR AN LAE: IF GAME GOES TO EXTRA TIME 15.20 Teamsheets given to Match Referee 1 7. 4 4 Toss & updated Teamsheets to Referee 15.38 An Cabhán amach ar an pháirc 17.45 Start of Extra Time 1st Half 15.41 Dún na nGall amach ar an pháirc 17.56* End of Extra Time 1st Half 15.45 Oifigigh an Chluiche amach ar an pháirc Teams Remain on the Pitch 15.52 Toss 17.58* Start of Extra Time 2nd Half 15.57 A Moment’s Silence 18.00* End of Extra Time 2nd Half 15.58 Amhrán na bhFiann 16.00 Tús an chluiche A water break will take place between IF STILL LEVEL, PHASE 2 (PENALTIES) the 15th & 20th minute of the half** 18:05 Players registered with the 16.38* Leath-am Referee & Toss An Cabhán to leave the field 18:07 Penalties immediately on half time whistle Dún na nGall to leave the field once An Cabhán have cleared the field 16.53* An dara leath A water break will take place between the 15th & 20th minute of the half** 17.35* Críoch an chluiche 38 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD FOCAL ÓN UACHTARÁN Fearadh na fáilte romhaibh chuig Craobhchomórtas programme. -

Ireland's Heritage of Geographical Names

Wiener Schriften zur Geographie und Kartographie, Vol. 18, Wien 2009, pp. 79–85 79 MAC GIOLLA EASPAI G , Dónall (Dublin/Baile Átha Cliath, Ireland)* Ireland’s heritage of geographical names Contents Summary 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................79 2 The historical corpus of Ireland’s place names .......................................................................................80 3 Non-Irish influence on place names ........................................................................................................81 4 The anglicisation of Ireland’s place names ..............................................................................................82 5 The restoration of Irish place-name forms ..............................................................................................82 6 The work of the Place Names Branch .....................................................................................................82 7 Place Names Database of Ireland ..........................................................................................................83 8 References .............................................................................................................................................84 Summary Geographical names have been central to Irish tradition from the dawn of history. The medieval Irish created a separate literary genre, the Dindshenchas, meaning ‘the lore of notable -

Neven Maguire (RTE Guide – December 2009) Neven Maguire's

Neven Maguire (RTE Guide – December 2009) Neven Maguire's Home Chef starts on RTÉ One on January 7 Neven Maguire is not what you'd expect from a celebrity chef. Polite, personable and without a bad word for anyone, the 37-year-old Cavan man seems almost too good to be a true blue kitchen devil. But he is the real deal, not only a great cook but a genuinely nice guy. "With me what you see is what you get," he says as if at loss as to how else he might describe himself. And if that phrase is hackneyed, it fits Maguire perfectly, a chef whose award-winning restaurant has put Blacklion on the culinary map and made a star of its unassuming yet ambitious proprietor. "I don't want to be the best there is," he says. "I want to be the best that I can be." Blacklion is a quiet country village on the northern edge of County Cavan. Neven Maguire was born and reared here in a three storey building that was once an old Garda station and is now McNean House and Restaurant. Voted Food and Wine magazine's Restaurant of the Year 2008, it is a homely establishment with Neven's wife, Amelda, working front of house. The couple live a few miles outside the village in a stylish single-storey dwelling in which Maguire's last TV series (Food From The Sun )and his latest, Neven Maguire's Home Chef, was filmed. This series ties in with his seventh, and latest, cookbook of the same name: a user-friendly guide with recipes tried and tested in his restaurant where the local is treasured. -

The Irish Standard. (Minneapolis, Minn. ; St. Paul

I ^-,=? * *• i . 1 I ,l *p ^,-" 4" l' ~ v Tf^ ' ^ v *WY- , "7 s ^ * THE IRISH STANDARD Saturday, May 6, 1916. French make) and a large pike and MEATH. mel decided to promote a testimonial President of Insurance Fund—T. J. ST. LOUIS COUNTY. crook' slashers, with hickory handle St. Patrick's Pay was Gaelic League Doyle, St. Paul. to M. J. Casey, who is retiring from Secretary of Insurance — Thomas County President John Simons, 511 was made near the premises. The Flag Day in Navan and a satisfactory the managership of the local branch Welch, Stillwater. N. 13th Ave. E., Duluth, Minn. Stale Treasurer of Insurance—John i illes were of the olden type and were sum was realized. The following col of the National bank, after 52 years' Sheeliy, Montgomery. Division No. l, Duiuth—President covered with rust. lected: P. Conroy, W. J. and J. Ken service. State Medical Director—Dr. J. V. William F. Murnlan, 509 E. 3rd St; r News from Ireland O'Connor, St. Paul. Vice Pres., John F. Scanlon, 107 ft W. The death took place on the 14th nedy; J. Reillv and B. Reilly, P. and An extensive range of buildings Director of Insurance Fund — John 5th St.; Fin. and Ins. Sec., W. J. Mc- Moran, Minneapolis; K J. McManua, St Bride, 7 W. 5th St.; Rec. Sec., W. J. ij'st. of an old and respected citizen B. Clarke. The usual annual collec used by Messrs. John O'Donnell & Co. Paul; P. L,. Cummings, Minneapolis; J. Lynott, 1224 E. 3d St.; Treas., J. -

COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 1

JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY CAVAN JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 2 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY CAVAN JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 3 Foreword The Architectural Inventory of County The NIAH survey of the architectural Cavan was carried out in 2012. A total of 860 heritage of County Cavan can be accessed structures were recorded. Of these some 770 on the internet at: are deemed worthy of protection. www.buildingsofireland.ie The Inventory should not be regarded as exhaustive as, over time, other buildings and structures of merit may come to light. The purpose of the Inventory and of this NATIONAL INVENTORY of ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE Introduction is to explore the social and historical context of the buildings and to facilitate a greater appreciation of the built heritage of County Cavan. 3 JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 4 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY CAVAN CUILCAGH LANDSCAPE In contrast to the predominant drumlin landscape of Cavan, wilder, exposed landscapes characterise the long and narrow western portion of the county, with great expanses of blanket upland bogs contrasted against the prominent outline of Cuilcagh, part of the Cuilcagh Mountain range shared with county Fermanagh. JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 5 Introduction Cavan is the most southerly county of uplands lies the cradle of the Shannon, a deep Ulster. -

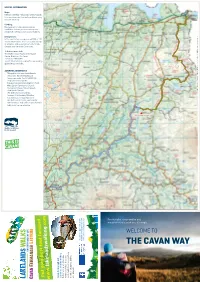

The Cavan Way

USEFUL INFORMATION Maps: Relevant OSI Map – Discovery Series Map 26. It is recommended that walkers always carry relevant OSI map. Clothing: Be prepared for changeable weather conditions. Ensure you have waterproof/ windproof clothing as well as sturdy boots. Emergencies: In the event of an emergency call 999 or 112. Tourist Information: There are a wide variety of activities and attractions on offer in the Geopark and the wider Cavan area. To find out more visit; The Market House Tourist Information Centre, Blacklion, Co. Cavan. T: (+353) 719853941 Tourist Information/Tea & Coffee and walking guides/maps available. Cavan Burren Park ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • This publication was funded under the project Harnessing Natural Resources under the INTERREG IVA Programme through the European Regional Development Fund. • West Cavan Community Council. • Marble Arch Caves Global Geopark. • Irish Sports Council. © Ordnance Survey Ireland, Licence No. 2014/01/CCMA/CavanCountyCouncil • The Ordnance Survey Office. • Seamus O’ hUltacháin, Blacklion. • A special word of appreciation is due to the local farming community without whose help and co-operation this walk would not be available. The Shannon Pot Forest walks, road rambles and megalithic trails await you, it’s magic.. WELCOME TO This project is supported by the EU’s the by supported is project This managed Programme, IVA INTERREG Body Programmes EU Special by the THE CAVAN WAY .com lakelandswalking ww. Put your best foot forward forward foot best your Put Cavan, Fermanagh and Fermanagh Cavan, walking. for ideal are Leitrim terrains, of array vast a With and forest lakes, mountains, something is there walks castle abilities strengths, all suit to interests. -

0262 Cavan County Council

Submission by Cavan County Council National Planning Framework Consultation legend Dublin. <;""v,,"~nid,"" :N3IM3f D"hl •••• B"o.If;oo;ICllnirinrcM1J ~ March 2017 Chief Executive J_ Cathaoirleach go-::- Do/ '--< Introduction Cavan County Council welcomes the publication of the consultation documents from the National Planning Framework and the opportunity to make a submission. Having considered the consultation documents, Cavan County Council highlight the following key strategic aspects to be considered as part of the National Planning Framework preparation. Role within Region There are a number of different functional areas within the Northern and Western Region. It is important that the National Panning Framework recognises such functional areas and the unique role that each functional area plays within the wider economy. The Cavan/Monaghan sub-region is one such function area. Each functional area needs to have a designation primary urban centre and Cavan Town is positioned to act as the principal town in this regard in terms of housing, job and education delivery. In addition to being the largest population centre in the region by a notable distance, it contains strategic facilities such as a hospital, Cavan Institute, Agricultural College, Cathedral and Sports Stadium, essential for sustainable growth. Cavan's strategic significance in further evident as within a GO-minute drive, a total population of approximately 1.3 million is within its catchment with an active workforce exceeding SOO,OOOpersons. Economic Growth There is opportunity to build on traditional sectors of the economy in Cavan such as agribusiness, food and engineering to assist in the future economic success of the Region. -

IRISH PASSENGER LISTS Published in U.S. Newspapers

IRISH PASSENGER LISTS Published in U.S. Newspapers Thomas Jay Kemp IRISH PASSENGER LISTS Published in U.S. Newspapers Thomas Jay Kemp © Copyright 2020, GenealogyBank Cover Illustration Photo: Dunluce Castle, County Antrim, Ireland Credit: Kenneth Allen; Wikimedia Commons © 2020 NewsBank All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America GenealogyBank, a division of NewsBank, Inc. 5801 Pelican Bay Boulevard, Suite 600 Naples, Florida 34108 www.GenealogyBank.com (866) 641-3297 About GenealogyBank GenealogyBank is a leading online genealogical resource from NewsBank, Inc. GenealogyBank’s exclusive newspaper archive features over 13,000+ small town and big city historical newspapers across the U.S. from 1690 to present day to help you discover and document your family story. You’ll find births, marriages, engagement notices, hometown news, obituaries and much more! Search today and get a glimpse into the triumphs, troubles and everyday experiences of your American ancestors. NewsBank, Inc. has been one of the world’s premier information providers for more than 35 years. Through partnerships with the American Antiquarian Society, Wisconsin Historical Society and more than 3,000 publishers, NewsBank is uniquely qualified to offer some of the most comprehensive genealogical information available – and to provide new content regularly. About the Author Thomas Jay Kemp is a librarian and archivist. He is the author of dozens of reference books and hundreds of articles about genealogy and family history. Tom previously served as the Chair of the National Council of Library & Information Associations (Washington, D.C.) and as Library Director of both the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the New England Historic Genealogical Society. -

A Letter from Ireland

A Letter from Ireland Mike Collins lives just outside Cork City, Ireland. He travels around the island of Ireland with his wife, Carina, taking pictures and listening to stories about families, names and places. He and Carina blog about these stories and their travels at: www.YourIrishHeritage.com A Letter from Ireland Irish Surnames, Counties, Culture and Travel Mike Collins Your Irish Heritage First published 2014 by Your Irish Heritage Email: [email protected] Website: www.youririshheritage.com © Mike Collins 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. All quotations have been reproduced with original spelling and punctuation. All errors are the author’s own. ISBN: 978-1499534313 PICTURE CREDITS All Photographs and Illustrative materials are the authors own. DESIGN Cover design by Ian Armstrong, Onevision Media Your Irish Heritage Old Abbey Waterfall, Cork, Ireland DEDICATION This book is dedicated to Carina, Evan and Rosaleen— my own Irish Heritage—and the thousands of readers of Your Irish Heritage who make the journey so wonderfully worthwhile. Contents Preface ...................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................ 4 Section 1: Your Irish Surname ....................................... -

The 1641 Rebellion in North-‐East Connacht

The 1641 Rebellion in North-East Connacht The cause and nature of the rebellion in co. Leitrim, co. Sligo and co. Roscommon J.C. Slieker s1041967 M.A.-thesis 7th of July 2015 Dr. R.P. Fagel 30 ECTS 2 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Illustrations 4 Introduction 8 DissertAtion Outline 10 Primary literAture review: the 1641 DePositions 12 Causes of the 1641 Rebellion 15 The 1641 Rebellion 19 The geography of North-East Connacht and the spread of the 1641 Rebellion 24 Leitrim 24 Sligo 30 Roscommon 35 Conclusion 41 Identifying the perpetrators 43 The involvement of the ‘noble’ GAelic Irish fAmilies 43 The involvement of the Old English 49 The involvement of the clergy 51 The involvement of other segments of society 53 ‘Foreign’ involvement 56 Conclusion 59 The PerPetrAtors motives to rebel 61 Religion 61 Ethnicity 63 King Charles I 64 Peer-pressure 67 PersonAl motivAtions 68 Conclusion 69 Conclusion 71 A GAelic CAtholic Rebellion? 71 Top-down or bottom-up? 73 1641 Rebellion or 1641 Rebellions? 75 Bibliography 79 3 Acknowledgements I would like to exPress my grAtitude to my suPervisor RAymond FAgel for his useful comments, remarks And engAgement throughout the Process of writing this master thesis. Furthermore I would also like to thank Pádraig Lenihan for his advice on the subject of my thesis And his sincere and valuable guidance during my time At the National University of IrelAnd, GalwAy. Special thanks are also given to the staff of the Special Collection At the JAmes HArdiman LibrAry, NUIG, for Providing me with the necessary facilities for conducting my reseArch. -

County Cavan

THE FLORA OF COUNTY CAVAN P.A. Reilly Occasional Papers No. 13 Published by the National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin 2001 ISSN 0792-0422 THE FLORA OF COUNTY CAVAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 THE PHYSICAL LANDSCAPE . 2 GEOLOGICAL MAP OF Co. CAVAN . 5 LANDSCAPE HISTORY . 8 BOTANICAL EXPLORATION . 12 SOCIAL AND LAND-USE CHANGES . 22 THE FLORA (Species list) . 32 Appendix 1 Botanical records from 1726 to 1898 . 129 Appendix 2 Supplements to Praeger’s Irish Topographical Botany (1901) . 135 Appendix 3 Botanical records from 1898 to 1998 . 145 Appendix 4 Areas of Scientific interest in Cavan . 149 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 153 MAP OF Co. CAVAN. Showing the major towns, lakes, rivers, mountains and botanical districts mentioned in the text. 158 TOPOGRAPHICAL INDEX . 159 INDEX OF SCIENTIFIC AND COMMON NAMES . 165 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work could not have been completed without the generous help and guidance given to me by Donal Synnott, Director of the National Botanic Gardens, Dublin who carefully read the manuscript, made improving recommendations and advised on Irish names. I am also indebted to him for permission to use the library and for access to the herbarium. I thank Matthew Jebb, the Taxonomist and Publications Editor, National Botanic Gardens, for his recommendations on work in progress, his editing, design and layout of the text and maps. I must also acknowledge the contribution of Charles Nelson, Taxonomist at the Gardens from 1976-1995, who read the first version and gave advice and encouragement. I thank the staff at Glasnevin: Maura Scannell, former Head of the Herbarium, to whom I am indebted for botanical guidance and many records, Sarah Ball the Librarian, for much help with my research, Berni Shine, Grace Pasley and Howard Fox of the Herbarium for answering my numerous queries and other assistance. -

Farnham Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 95 FARNHAM PAPERS MS 3,117-3,118; 3,133-3,134; 3,502-3,508; 4,103-4,104; 5,010-5,013; 5,504-5,506; 8,527; 11,490-11,499; 13,340; 18,419; 18,600-18,635; 19,091-19,147; 28,834 /3; 28,836 /8; 28,842 /20-21 & 41,113-41,175. D. 15,409; 18,572; 18,646-18,649; 18,672; 20,409-20,475 & 22,781. Maps: 15. B. 8 /7, 21. F. 115-120 & MS Maps 278-281. A collection of estate and family papers of the Maxwell family, Barons, Viscounts and Earls of Farnham of Farnham House, county Cavan, circa 1600- circa 1950. Compiled by Dr Jonathan Cherry holder of the Studentship in Irish History provided by the National Library of Ireland in association with the National Committee for History. 2004-2005. Contents INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................4 THE MAXWELL FAMILY OF FARNHAM ........................................................................4 THE ESTATES...............................................................................................................5 THE FARNHAM PAPERS ...............................................................................................8 ARRANGEMENT OF THE COLLECTION ..........................................................................9 SOURCES & BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................9 I LEGAL PAPERS...............................................................................................11