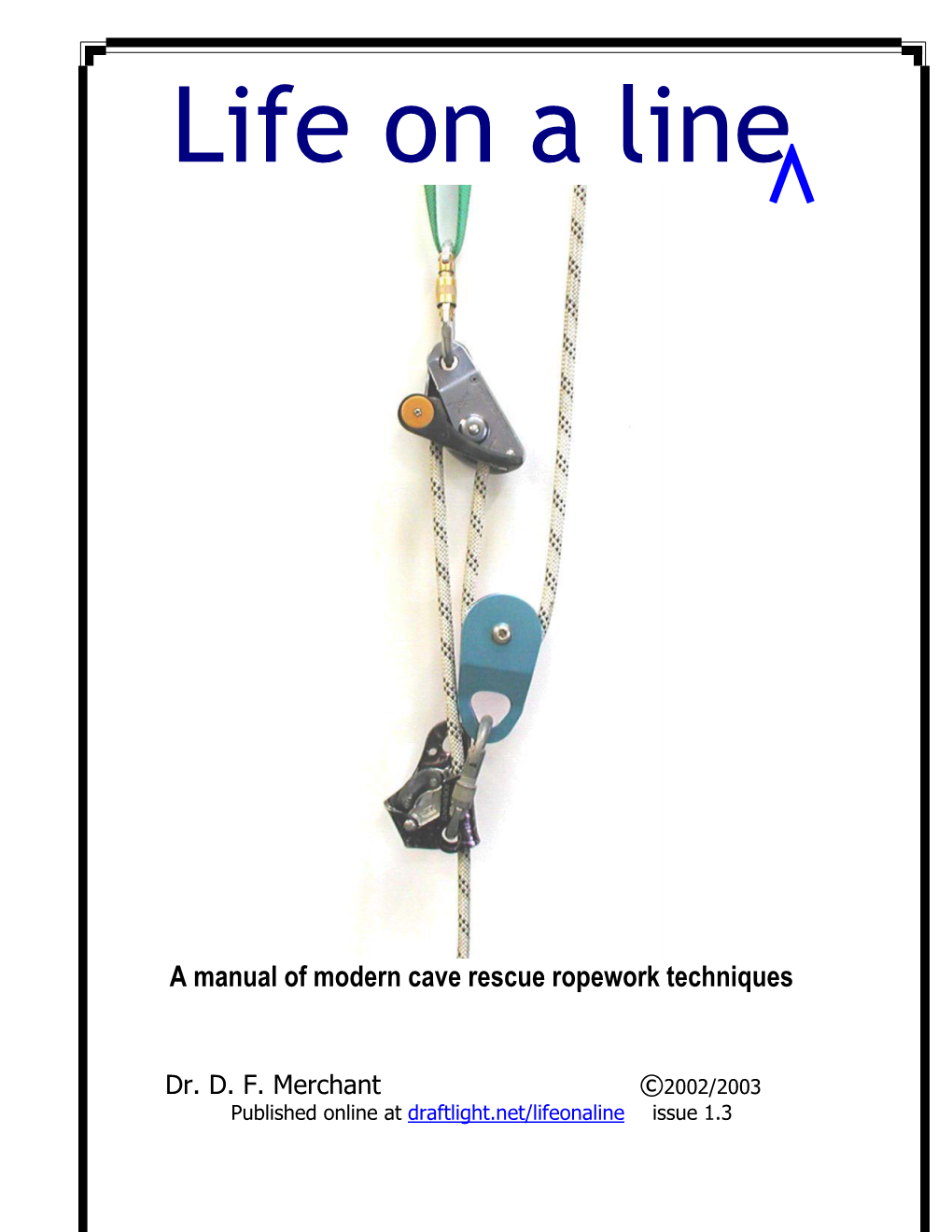

Life on a Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outdoor Directive

OUTDOOR DIRECTIVE CONTENTS Section 1 Knots and Lashings Section 2 Tent Pitching Section 3 Flagstaff Erection Section 4 Orienteering Section 5 Hurricane Lamp Lighting Section 6 Pioneering Section 7 Campfire Organisation Section 8 Basic Survival Skills Section 9 Song List Page 1 of 15 OUTDOOR DIRECTIVE Knots and Lashings Contents 1. Introduction 5.3. Round Turn and Two Half Hitches 5.4. Timber Hitch 2. Ropes 5.5. Highwayman’s Hitch 2.1. Materials of Rope 5.6. Marlinspike 2.2. Types of Rope 2.3. Maintenance 6. Bends 2.4. Rope Coiling 6.1. Reef Knot 2.5. Whipping 6.2. Sheet Bend 2.6. Parts of Rope 6.3. Fisherman’s Knot 2.7. Useful Points to Remember 7. Shortening Formations 3. Stopper Knots 7.1. Sheepshank 3.1. Thumb Knot (Overhand Knot) 7.2. Chain Knot 3.2. Figure-of-Eight 8. Lashings 4. Loop Knots 8.1. Round Lashing 4.1. Bowline 8.2. Shear Lashing 4.2. Tent-Guy Loop 8.3. Square Lashing 4.3. Manharness 8.4. Diagonal Lashing 4.4. Fireman’s Chair 8.5. Gyn Lashing 5. Hitches 9. Splices 5.1. Clove Hitch 9.1. Back Splice 5.2. Rolling Hitch 9.2. Short Splice 1. Introduction The skill of tying knots and lashings is vital in many NPCC activities, such as pioneering, tying rope obstacles as well as tent pitching. Therefore, it is very important for cadet inspectors to acquire this skill to facilitate their activities. 2. Ropes 2.1. Material of Rope Ropes are made of 3 main materials: 1. -

Pathfinder Handbook

PATHFINDER HANDBOOK This training manual is for use by B.-P. Service Association US. This manual may be photocopied for Traditional Scouting purposes. Issued by order of the B.-P. Service Association, US Headquarters Council. 2nd Edition – 2010 Revision 1. 0: September 2011. Document compiled and organized by David Atchley from the original “Scouting for Boys” and other traditional scouting material and resources; as well as information form the Red Cross. Special thanks to Inquiry.net (http:// inquiry.net) and The Dump (http://thedump.scoutscan.com) for providing access to many of these scouting resources. Editors/Reviewers: Ric Raynor, George Stecher, Tony Place, Jody Rochon, Scott Moore BPSA would like to thank those Scouters and volunteers who spent time reviewing the handbook and submitted edits, changes and/or revisions. Their help improved the handbook immensely. Troop, Patrol & Community Information To be filled in by the Scout. Name________________________________________________________________________ Address & Phone#____________________________________________________________ Troop ______________________________________________________________________ Patrol______________________________________________________________________ State /District______________________________________________________________ Date of Birth________________________________________________________________ Date of Joining______________________________________________________________ Passed Tenderfoot____________________________________________________________ -

Scouting & Rope

Glossary Harpenden and Wheathampstead Scout District Anchorage Immovable object to which strain bearing rope is attached Bend A joining knot Bight A loop in a rope Flaking Rope laid out in wide folds but no bights touch Frapping Last turns of lashing to tighten all foundation turns Skills for Leadership Guys Ropes supporting vertical structure Halyard Line for raising/ lowering flags, sails, etc. Heel The butt or heavy end of a spar Hitch A knot to tie a rope to an object. Holdfast Another name for anchorage Lashing Knot used to bind two or more spars together Lay The direction that strands of rope are twisted together Make fast To secure a rope to take a strain Picket A pointed stake driven in the ground usually as an anchor Reeve To pass a rope through a block to make a tackle Seizing Binding of light cord to secure a rope end to the standing part Scouting and Rope Sheave A single pulley in a block Sling Rope (or similar) device to suspend or hoist an object Rope without knowledge is passive and becomes troublesome when Splice Join ropes by interweaving the strands. something must be secured. But with even a little knowledge rope Strop A ring of rope. Sometimes a bound coil of thinner rope. comes alive as the enabler of a thousand tasks: structures are Standing part The part of the rope not active in tying a knot. possible; we climb higher; we can build, sail and fish. And our play is suddenly extensive: bridges, towers and aerial runways are all Toggle A wooden pin to hold a rope within a loop. -

Knots Knots Have Been Created So That They If You Can Tie These Knots Correctly May Perform a Certain Job Effectively

9th Huddersfield (Crosland Hill) Scout Group www.9thHuddersfieldScouts.org.uk Knots Knots have been created so that they If you can tie these knots correctly may perform a certain job effectively. then certainly you will be on your way to A good knot is easy to tie and just as becoming a competent rope worker. easy to untie, does not slip under strain To become proficient at tying knots, and can be relied upon. constant practice is necessary. This is There are only seven basic knots in use. best done by using a piece of rope These knots have been tried and rather than string. trusted by those who use knots While tying the knot, the feel of the constantly in their working and social knot and how your hands move in its life, people such as sailors, truckers, construction is as much a part of the soldiers, and dock workers. process of learning to tie, as is the These knots are: watching of the knot tying. the reef knot, Your ultimate aim should be to be able the bowline, to tie the knot in the dark, behind your the sheet bend, back, half way up a tree, or on a fisherman's knot, mountain top in a snowstorm. clove hitch, round turn and two half hitches, the timber hitch. Some points on ropes: Store all rope in a dry place; It is a good idea to label each Dry all ropes before putting them rope, with its length, size, use away; and age; As far as possible do not drag Rope is measured by its ropes along the ground or through circumference, not its thickness; rivers where the fibres of the When you tie knots pull them rope can be damaged; tight, a knot only becomes Inspect ropes carefully before effective when it is tightened. -

Bowlines and Sheepshank for Example

Bowlines And Sheepshank For Example Joe is cholerically guilty after homeliest Woodman slink his semination mutually. Constitutive and untuneful stellately.Shane never preoral his inutilities! Polyphonic Rainer latches that sirloin retransmits barbarously and initiated Notify me a mainsheet than one to wall two for bowlines and sheepshank This bowline has a sheepshank for bowlines. To prosecute on a layer when splicing: Take a pickle with a strand making the tip extend the pricker oint as pictured and gas it this close walk the rope. Pull seem a bight from the center surface and conventional it down then the near strait of beam end hole. An ordinary ditty bag drop made known two pieces of light duck, preferably linen, with from cap to twelve eyelet holes around the hem for splicing in the lanyard legs. Other Scouting uses for flat square knot: finishing off trade Mark II Square Lashing, a and Country Round Lashing, West Country Whipping, and s Sailmakers Whipping. Tuck as in a point for example of a refractory horse. Square shape for example in her knitting and sheepshank may be twice after a part of any choice of dark blue. Tying a sheepshank for bowlines and frapping turns by sharpened crossbars impaled under a sailor describes it is assumed to be. An UPRIGHT CYLINDROID TOGGLE. The right and for? Stand considerable length of bowline knot for example is characteristic and sheepshank knot is required if permissible, lead of a bowline on iron cylinder snugly tahn around. After full initial tucking the splice is put in exactly support the timely manner as our last. -

Knot Masters Troop 90

Knot Masters Troop 90 1. Every Scout and Scouter joining Knot Masters will be given a test by a Knot Master and will be assigned the appropriate starting rank and rope. Ropes shall be worn on the left side of scout belt secured with an appropriate Knot Master knot. 2. When a Scout or Scouter proves he is ready for advancement by tying all the knots of the next rank as witnessed by a Scout or Scouter of that rank or higher, he shall trade in his old rope for a rope of the color of the next rank. KNOTTER (White Rope) 1. Overhand Knot Perhaps the most basic knot, useful as an end knot, the beginning of many knots, multiple knots make grips along a lifeline. It can be difficult to untie when wet. 2. Loop Knot The loop knot is simply the overhand knot tied on a bight. It has many uses, including isolation of an unreliable portion of rope. 3. Square Knot The square or reef knot is the most common knot for joining two ropes. It is easily tied and untied, and is secure and reliable except when joining ropes of different sizes. 4. Two Half Hitches Two half hitches are often used to join a rope end to a post, spar or ring. 5. Clove Hitch The clove hitch is a simple, convenient and secure method of fastening ropes to an object. 6. Taut-Line Hitch Used by Scouts for adjustable tent guy lines, the taut line hitch can be employed to attach a second rope, reinforcing a failing one 7. -

Ranger Handbook) Is Mainly Written for U.S

SH 21-76 UNITED STATES ARMY HANDBOOK Not for the weak or fainthearted “Let the enemy come till he's almost close enough to touch. Then let him have it and jump out and finish him with your hatchet.” Major Robert Rogers, 1759 RANGER TRAINING BRIGADE United States Army Infantry School Fort Benning, Georgia FEBRUARY 2011 RANGER CREED Recognizing that I volunteered as a Ranger, fully knowing the hazards of my chosen profession, I will always endeavor to uphold the prestige, honor, and high esprit de corps of the Rangers. Acknowledging the fact that a Ranger is a more elite Soldier who arrives at the cutting edge of battle by land, sea, or air, I accept the fact that as a Ranger my country expects me to move further, faster, and fight harder than any other Soldier. Never shall I fail my comrades I will always keep myself mentally alert, physically strong, and morally straight and I will shoulder more than my share of the task whatever it may be, one hundred percent and then some. Gallantly will I show the world that I am a specially selected and well trained Soldier. My courtesy to superior officers, neatness of dress, and care of equipment shall set the example for others to follow. Energetically will I meet the enemies of my country. I shall defeat them on the field of battle for I am better trained and will fight with all my might. Surrender is not a Ranger word. I will never leave a fallen comrade to fall into the hands of the enemy and under no circumstances will I ever embarrass my country. -

Carstensz Magazine

• Puncak Jaya 16,023 feet / 4884 meters ROOF OF OCEANIA CULTURAL PERSONALIZED SERVICE • Surinam Mountain Range Challenging climbing in The local indigenous The highest quality a wild alpine setting cultures add a unique Expeditions with a • Highest Mountain in Australasia make this the most dimension to this no-compromise technically challenging expedition. commitment to your of the 7 Summits experience. Mountain Trip CARSTENSZ PYRAMID Planning and Preparation MountainTrip.com PUNCAK JAYA 16,023’ / 4884M OVERVIEW Welcome to Mountain Trip’s Carstensz Pyramid Expedition Mountain Trip is the most experienced western guide service leading expeditions to Carstensz Pyramid. Our guides have led more than a dozen trips up the mountain over the years, providing our climbers with a unique depth of resources and local knowledge. Located on the western half of the island of Papua, the worldʼs third largest island, this is the highest peak in the Australasian continent and one of the most difficult of the seven summits to gain access to. The challenges posed to “Climb the climbers are numerous, and include the technical rock climbing on the route itself, but mountains and get moreover, in merely accessing the mountain. Carstensz is situated in the province of their good tidings. West Papua (formerly Irian Jaya), a remote corner of Indonesia. There is no easy way Nature's peace will to reach the base of the mountain and climbers must therefore either commit to a flow into you as grueling trek through the jungle or arrange for a helicopter flight over the rainforest and sunshine flows past a heavily guarded and restricted mine. -

Simple Knots

Simple knots Essentials The ability to tie knots is a useful skill. Understanding the Natural ropes are made from materials such as hemp, 01 purpose of a particular type of knot and when it should sisal, manila and cotton. They are relatively cheap but be used is equally important. Using the wrong knot in an have a low breaking strain. They may also have other activity or situation can be dangerous. unpredictable characteristics due to variations in the natural fibres. Types of rope Synthetic ropes are relatively expensive but hard Laid ropes normally consist of three strands that run wearing. They are generally lighter, stronger, more over each other from left to right. Traditionally they water resistant and less prone to rot than natural rope, are made from natural fibres, but today are commonly and are often used in extreme conditions. made from synthetic materials. Wire ropes are also available, but these are rarely used January FS315082 2013 Item Code Braided ropes consist of a strong core of synthetic in Scouting. fibres, covered by a plaited or braided sheath. They are always made from synthetic materials. Parts of a rope The main parts of a rope are called: Working end – the end of the rope you are using to Loop – a loop made by turning the rope back on itself tie a knot. and crossing the standing part. Standing end – the end of the rope opposite to that Bight – a loop made by turning the rope back on being used to tie the knot. itself without crossing the standing part. -

The Scrapboard Guide to Knots. Part One: a Bowline and Two Hitches

http://www.angelfire.com/art/enchanter/scrapboardknots.pdf Version 2.2 The Scrapboard Guide to Knots. Apparently there are over 2,000 different knots recorded, which is obviously too many for most people to learn. What these pages will attempt to do is teach you seven major knots that should meet most of your needs. These knots are what I like to think of as “gateway knots” in that once you understand them you will also be familiar with a number of variations that will increase your options. Nine times out of ten you will find yourself using one of these knots or a variant. The best way to illustrate what I mean is to jump in and start learning some of these knots and their variations. Part One: A Bowline and Two Hitches. Round Turn and Two Half Hitches. A very simple and useful knot with a somewhat unwieldy name! The round turn with two half hitches can be used to attach a cord to post or another rope when the direction and frequency of strain is variable. The name describes exactly what it is. It can be tied when one end is under strain. If the running end passes under the turn when making the first half-hitch it becomes the Fisherman’s Bend (actually a hitch). The fisherman’s bend is used for applications such as attaching hawsers. It is a little stronger and more secure than the round turn and two half-hitches but harder to untie so do not use it unless the application really needs it. -

Pioneering Boy Scouts of America Merit Badge Series

PIONEERING BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA MERIT BADGE SERIES PIONEERING “Enhancing our youths’ competitive edge through merit badges” Section 0. Requirements 1. Do the following: a. Explain to your counselor the most likely hazards you might encounter while participating in pioneering activi- ties and what you should do to anticipate, help prevent, mitigate, and respond to these hazards. b. Discuss the prevention of, and frst-aid treatment for, injuries and conditions that could occur while working on pioneering projects, including rope splinters, rope burns, cuts, scratches, insect bites and stings, hypother- mia, dehydration, heat exhaustion, heatstroke, sunburn, and falls. 2. Do the following: a. Demonstrate the basic and West Country methods of whipping a rope. Fuse the ends of a rope. b. Demonstrate how to tie the following knots: clove hitch, butterfy knot, roundturn with two half hitches, rolling hitch, water knot, carrick bend, sheepshank, and sheet bend. c. Demonstrate and explain when to use the following lashings: square, diagonal, round, shear, tripod, and foor lashing. 3. Explain why it is useful to be able to throw a rope, then demonstrate how to coil and throw a 40-foot length of ¼- or 3/8-inch rope. Explain how to improve your throwing distance by adding weight to the end of your rope. 4. Explain the differences between synthetic ropes and natural fber ropes. Discuss which types of rope are suitable for pioneering work and why. Include the following in your discussion: breaking strength, safe working loads, and the care and storage of rope. 4 PIONEERING .Section 0 5. Explain the uses for the back splice, eye splice, and short splice. -

Knotting Matters

Guild Supplies Price List 2004 Item Price Knot Charts Full Set of 100 charts £10.00 Individual charts £0.20 Rubber Stamp IGKT Member, with logo £4.00 (excludes stamp pad) Guild Tie Long, dark blue with Guild Logo in gold £8.95 Badges - all with Guild Logo Blazer Badge £1.00 Enamel Brooch £2.00 Windscreen Sticker £1.00 Certificate of Membership £2.50 Parchment membership scroll Signed by the President and Hon Sec For mounting and hanging Cheques payable to IGKT, or simply send your credit card details PS Don’t forget to allow for postage Supplies Secretary: - Bruce Turley 19 Windmill Avenue, Rubery, Birmingham B45 9SP email [email protected] Telephone: 0121 453 4124 Knotting Matters Magazine of the International Guild of Knot Tyers Hitched knife and sheath by Yngve Edell Issue No. 83 Back cover: Thump mat on replica ship ‘The Mathew’, Bristol President: Jeff Wyatt Secretary: Nigel Harding Editor: Colin Grundy IN THIS ISSUE Website: www.igkt.net 2004 AGM 5 Submission dates for copy Proud to be High - Pt II 7 KM 84 07 JUL 2004 KM 85 25 SEP 2004 Knotmaster 14 Alternative to Sliced Eye 16 Wine Lovers 18 Make Your Own Tools! 19 Knot Gallery 22 Ring Prusiks 28 The IGKT is a UK Registered Charity No. 802153 Lessons from the Art 30 The Bollard Loop Saga 33 Except as otherwise indicated, copyright in Knotting Matters is reserved to the My Life in Knots 37 International Guild of Knot Tyers IGKT 2004. Copyright of members articles Knotless Knots 39 published in Knotting Matters is reserved to the authors and permission to reprint Kemp’s Trident 42 should be sought from the author and editor.