Findings from Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roco Wat I Acoli

Roco Wat I Acoli Restoring Relationships in Acholi‐land: Traditional Approaches to Justice and Reintegration September, 2005 Liu Institute for Global Issues Gulu District NGO Forum Ker Kwaro Acholi FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPHY Left: The Oput Root used in the Mato Oput ceremony, Erin Baines Centre: Dancers at a communal cleansing ceremony, Lara Rosenoff Right: A calabash holding the Oput and Kwete brew, Erin Baines BACK COVER PHOTOGRAPHY Background: Winnower for holding the Oput, and knife to slaughter sheep at a Mato Oput Ceremony, Carla Suarez Insert: See above © 2005 ROCO WAT I ACOLI Restoring Relations in Acholi‐land: Traditional Approaches To Reintegration and Justice Supported by: The John D. and Catherine T. Macarthur Foundation The Royal Embassy of the Netherlands Prepared by: Liu Institute for Global Issues Gulu District NGO Forum With the assistance of Ker Kwaro Acholi September, 2005 Comments: [email protected] or Boniface@human‐security‐africa.ca i Roco Wat I Acoli ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The 19 year conflict in northern Uganda has resulted in one of the world’s worst, most forgotten humanitarian crisis: 90 percent of the affected-population in Acholi is confined to internally displaced persons camps, dependant on food assistance. The civilian population is vulnerable to being abducted, beaten, maimed, tortured, raped, violated and murdered on a daily basis. Over 20,000 children have been abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and forced into fighting and sexual slavery. Up to 40,000 children commute nightly to sleep in centres of town and avoid abduction. Victims and perpetrators are often the same person, and currently there is no system of accountability for those most responsible for the atrocities. -

Important Bird Areas in Uganda. Status and Trends 2008

IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS IN UGANDA Status and Trends 2008 NatureUganda The East Africa Natural History Society Important Bird Areas in Uganda Status and Trends 2008 Compiled by: Michael Opige Odull and Achilles Byaruhanga Edited by: Ambrose R. B Mugisha and Julius Arinaitwe Map illustrations by: David Mushabe Graphic designs by: Some Graphics Ltd January 2009 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non commercial purposes is authorized without further written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Production of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written notice of the copyright holder. Citation: NatureUganda (2009). Important Bird Areas in Uganda, Status and Trends 2008. Copyright © NatureUganda – The East Africa Natural History Society About NatureUganda NatureUganda is a Non Governmental Organization working towards the conservation of species, sites and habitats not only for birds but other taxa too. It is the BirdLife partner in Uganda and a member of IUCN. The organization is involved in various research, conservation and advocacy work in many sites across the country. These three pillars are achieved through conservation projects, environmental education programmes and community involvement in conservation among others. All is aimed at promoting the understanding, appreciation and conservation of nature. For more information please contact: NatureUganda The East Africa Natural History Society Plot 83 Tufnell Drive, Kamwokya. P.O.Box 27034, Kampala Uganda Email [email protected] Website: www.natureuganda.org DISCLAIMER This status report has been produced with financial assistance of the European Union (EuropeAid/ ENV/2007/132-278. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of Birdlife International and can under no normal circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. -

NWOYA BFP 2015-16.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 606 Nwoya District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 606 Nwoya District Foreword Nwoya District Local Government continues to implement decentralized and participatory development planning and budgeting process as stipulated in the Local Government Act CAP 243 under section 36(3). This Local Government Budget Framework Paper outlines district's intended interventions for social and economic development in FY 2015/16. The development budget proposals earmarked in this 2015/16 Budget Framework Paper focus on the following key priority areas of; Increasing household incomes and promoting equity, Enhancing the availability of gainful employment, Enhancing Human capital, Improving livestock and quality of economic infrastructure, Promoting Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) and ICT to enhance competiveness, Increasing access to quality social services, Strengthening good governance, defence and security and Promoting a sustainable population and use of environment and natural resources in a bid to accelerate Prosperity For All. Acquisition of five acrea of land for the construction of Judiciary offices at Anaka T.C. This policy framework indentifies the revenue projections and expenditure allocation priorities. This will form the basis for preparation of detailed estimates of revenue and expenditure that shall be presented and approved by the District Council. In the medium term, the District will be committed to implement its policies and strategies towards achieving its Mission statement "To serve the Community through the coordinated delivery of services which focus on National and Local priorities and contribute to sustainable improvement of the quality of life of the people in the District". -

Marasa Africa Fact Sheet

MARASA AFRICA FACT SHEET PROPERTY ACCOMMODATION GUEST AMENITIES ACCESS CULINARY EXPERIENCE DESTINATION HIGHLIGHTS Paraa Safari • 25 Classic Guest • Free - Form • 337 km Entebbe • Captain’s Table Restaurant • Murchison Falls National Lodge Rooms Swimming pool International Airport • Nile Terrace Restaurant Park • 26 Deluxe Guest with views over the • 20 km Pakuba • Poolside Bar & Terrace • Located on the majestic Rooms Nile River Airfield • Bush Dinning along the Nile River, ‘Home of • 2 Wheelchair • Marasa Africa Spa • 12 km Bugungu shores of the Nile Hippos’ - +256 (0) 312 Friendly Guest & Fitness Centre Airstrip • Sundowner Cruise on the 260 260 Rooms (Included • Signature Pool Bar • 294 km Kampala Nile Delta Classic rooms) • Business Centre • Murchison Falls by Boat or • 2 Suites • Complimentary by Land • 3 Safari Tents Wi-Fi in the lodge • Game Drive Safari • The Queens public areas • Sports Fishing Cottage • Sundowners • Chimpanzee Tracking in and campfires Kaniyo Pabidi (Budongo overlooking the Forest) Nile • Nature Walks in Murchison Falls National Park and Budongo Forest. • Nile delta Cruise • Bird Watching in Kaniyo Pabidi (Budongo Forest) Mweya Safari • 16 Classic Guest • Marasa Africa Spa • 403 km Entebbe • Kazinga Restaurant and • Queen Elizabeth National Lodge Rooms & Fitness Centre International Airport Terrace Park • 28 Deluxe Guest • Poolside deck • 2 km Mweya Airstrip • Tembo Bar • Located on the Mweya Rooms overlooking the • 57 km Kasese • Poolside deck overlooking Peninsula • 2 Wheelchair Kazinga Channel Airstrip the -

Pdf | 305.92 Kb

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org Nwoya District: Humanitarian, Recovery and Development Organizations Presence by Sector per Sub-County (July 2010) ! Lukodi ! Ala Alero NWOYA DISTRICT Uganda Overview Degiya ADJUMANIDevelopment & ! S/N Humanitarian Sub-county Sudan Recovery Agency Presence INVISIBLE CHILDREN, WVU, WFP, ACF 4 1 LABE, SCiUG, CSG, CSG, ECHO- WTU-ABS Parabong ACTED 4 Congo BRAVO, AR, UNICEF ! (Dem. Rep) Coope AR! 4 ARC 4 Mon Roc ACTED, FAO, WFP, USAID/SPRING, ! 2 USAID-NUTI ECHO-BRAVO, AR, FTCU,WVU ARLPI 4 Kenya Lamogi Unyama ! AVSI! 3 3 AMURU CARE 4 Pagak Unyama 4 JICA ! CARITAS! 4 Tanzania UNDP, CARE, CPA 2 Rwanda Pawor 5 ! ACTED, M AP, LABE CPAR 4 Legend Oliavu ACF, UNICEF, CPAR, SCiUG, AVSI, CPAR-QIP 2 ! ! Villages 6 UNFPA, NUMAT, CSG, MAP, ARC, CRS 4 Pumit CSG 3 ! FTCU, CPAR, SCIUG,CRS DDG 4 Motorable Road 10 Mutir UM AC, UNDP, DDG Alokolum ! ECHO-BRAVO 3 ! National Boundary NRC,WVU, CPA, WALOKOKWO, EMPOWERING HANDS 1 Wadelai !WCC, GUSCO, CPAR, CARITAS, FAO 3 7 District Boundary OHCHR,ARLPI, UNHCR, NUMAT, FTCU 1 GULU Te-tugu ! ARC, UNICEF GUSCOKoro ! 3 ALERO Koro- Sub-County Boundary GWDabili 2 8 Pakwinyo ! ! Ongako ! ! HAULaminabili 1 9 ACF, ARC, CPAR, UNICEF S/N Sector Information INVISIBLE CHILDREN 4 JICA 1 1 Education Ragem Bwobo LABE 4 ! ! MAP 3 Food Security and Alero MC 3 2 Agricultural ! NRC 4 Livelihoods Ongoko NUMAT 4 ! OHCHR 4 Non-Agricultural 3 SCiUGBarogal ! Palenga 4 ! Livelihoods UMAC 4 Olobodagi Koich Bobi ! ! UNDP! 4 UNFPA 4 4 Infrastructure Koich Paranga ! UNHCR! -

Resolving the Property Rights Dilemma

LAND TENURE, BIODIVERSITY AND POST-CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION IN ACHOLI SUB-REGION Resolving the Property Rights Dilemma Godber W. Tumushabe Arthur Bainomugisha Onesmus Mugyenyi ACODE Policy Research Series No. 29, 2009 Citation: Tumushabe, G., Bainomugisha, A., and Mugyenyi, O., (2009). Land Tenure, Biodiversity and Post Confl ict Transformation in Acholi Sub-Region: Resolving the Property Rights Dilemma. ACODE Policy Research Series No. 29, 2009. Kampala © ACODE 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this general exemption. ISBN: LAND TENURE, BIODIVERSITY AND POST- CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION IN ACHOLI SUB-REGION Resolving the Property Rights Dilemma Godber Tumushabe Arthur Bainomugisha Onesmus Mugyenyi Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment Kampala Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................v List of tables ..................................................................................................... v List of Boxes .................................................................................................... -

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

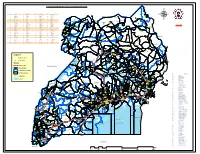

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Uganda National Roads Network

UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS NETWORK REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Musingo #" !P Kidepo a w K ± r i P !P e t Apoka gu a K m #" lo - g - L a o u k - #" g u P i #" n d Moyo!P g o i #"#" - t #"#" N i k #" KOBOKO M e g a #" #" #" l Nimule o #"!P a YUMBE #" u!P m ng m o #" e #" Laropi i #" ro ar KAABONG #" !P N m K #" (! - o - te o e om Kaabong#"!P g MOYO T c n o #" o #" L be Padibe !P - b K m !P LAMWO #" a oboko - Yu Yumbe #" om r K #" #" #" O #" Koboko #" #" - !P !P o Naam REGIONS AND STATIONS Moy n #" Lodonga Adjumani#" Atiak - #" Okora a #" Obongi #" !P #" #" a Loyoro #" p #" Ob #" KITGUM !P !P #" #" ong !P #" #" m A i o #" - #" - K #" Or u - o lik #" m L Omugo ul #" !P u d #" in itg o i g Kitgum t Maracha !P !P#" a K k #" !P #" #"#" a o !P p #" #" #" Atiak K #" e #" (!(! #" Kitgum Matidi l MARACHA P e - a #" A #"#" e #" #" ke d #" le G d #" #" i A l u a - Kitgum - P l n #" #" !P u ADJUMANI #" g n a Moyo e !P ei Terego b - r #" ot Kotido vu #" b A e Acholibur - K o Arua e g tr t u #" i r W #" o - O a a #" o n L m fe di - k Atanga KOTIDO eli #" ilia #" Rh #" l p N o r t h #"#" B ino Rhino !P o Ka Gulu !P ca #" #"#" aim ARUA mp - P #" #" !P Kotido Arua #" Camp Pajule go #" !P GULU on #" !P al im #" !PNariwo #" u #" - K b A ul r A r G de - i Lira a - Pa o a Bondo #" Amuru Jun w id m Moroto Aru #" ctio AMURU s ot !P #" n - A o #" !P A K i !P #" #" PADER N o r t h E a s t #" Inde w Kilak #" - #" e #" e AGAGO K #"#" !P a #" #" #" y #" a N o #" #" !P #" l w a Soroti e #"#" N Abim b - Gulu #" - K d ilak o b u !P #" Masindi !P i um !P Adilang n - n a O e #" -

The Grand Circuit

The Grand Circuit Day 1: Destination: Entebbe Drive: 10 km | 0.5 hour Welcome to Uganda! As soon as you enter the airport you will be embraced with a pleasant temperature and hopefully a charming smile of the immigration officer. Take this day to relax from your trip. Entebbe is a charming town, with a pleasant lakeside, some good restaurants and large swimming pool at Laiko Hotel. Accommodation options: Budget / Mid-range: Via Via Guesthouse Our favourite restaurants: Dine at the Boma Hotel, Carpe Diem Guesthouse, or eat fresh fish and great pizza at Gorreti’s, with your feet in the white sands viewing Lake Victoria. Day 2: Start: Entebbe Destination: Lake Mburo NP Drive: 225 km | 6+ hours Your road trip adventure starts today. Its a smooth and scenic ride to Lake Mburo National Park. Covered with extensive acacia woodlands, this park is one of the best places in the country to enjoy a walking safari and see the giant eland antelope, zebras and leopards. Accommodation options: Budget: Eagle's Nest Mid-range: Rwakobo Rock Day 3: Enjoy: Lake Mburo NP Enjoy a day in the park. With no dangerous predators such as lions, Lake Mburo is the best place to go on a guided safari by foot, bike or horse. Moreover, this is one of the few national parks in Africa allowing night game drives, which give you the chance to see some of the rare nocturnal animals like the mongoose, hyena, leopard and serval cat. The Grand Circuit Day 4: Start: Lake Mburo NP Destination: Lake Mutanda Drive: 225 km | 6+ hours Drive to the Kigezi Highlands, perhaps the most fertile and scenic region of Uganda. -

The Ultimate Uganda and Rwanda Gorilla Safari

THE ULTIMATE UGANDA AND RWANDA GORILLA SAFARI Experience brilliant trekking with Chimps and Gorillas, and enjoy a wildlife safari, in Uganda and Rwanda Gorilla tracking in Bwindi or Mgahinga, with further opportunity in Rwanda's Virunga National Park Rhino Sanctuary visit and Murchison Falls on the shores of the Nile Chimp trek in Kibale, Ishasha tree climbing lions & game drives Visit the lovely Lake Bunyonyi and Queen Elizabeth National Park HOLIDAY CODE URG Uganda, Rwanda, Wildlife, 14 Days 12 nights lodge, 1 night guesthouse, 13 breakfasts, 13 dinners, max group size: 14, 13 days wildlife/safari and activities, max altitude 2500 m www.keadventure.com UK: +44(0) 17687 73966 US (toll-free): 1-888-630-4415 PAGE 2 THE ULTIMATE UGANDA AND RWANDA GORILLA VIEW DATES, PRICES & BOOK YOUR HOLIDAY HERE Introduction This fabulous wildlife safari holiday to Uganda and Rwanda focuses on tracking the endangered Mountain Gorillas as well as the wildlife highlights of these countries. Our adventure begins with a ‘Rhino Walk' at the Ziwa Sanctuary to see these beautiful and also endangered giants. We then move to the Murchison Falls National Park where we enjoy boat rides, game drives on the shores of the River Nile, and see the famous waterfalls. Hippos, elephant and giraffe are all found on the river banks and gives us a lovely start to this two-week wildlife holiday.We then track chimpanzees in Kibale National Park (loads of elephants here as well) with its splendid views over to the Rwenzori Mountains, and pop to the Bigodi Wetlands for some further monkeys and to see its prolific birdlife. -

Paraa Safari Lodge

Paraa Safari Lodge Established in 1954, Paraa Safari Lodge is in Murchison Falls National Park. The lodge is located in the north west of Uganda over looking one of nature's best kept secrets, the River Nile, on its journey from its source at Lake Victoria to join Lake Albert – here it is suddenly channeled into a gorge only six meters wide, and cascades 43 meters below. The earth literally trembles at Murchison Falls - one of the world's most powerful flows of natural water. The safari décor of the lodge still reflects the bygone era of early explorers, enshrined with a modern touch. The luxurious pool overlooks the winding River Nile below, which was the setting for the classic Hollywood movie "The African Queen" (starring Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart). Paraa Safari Lodge offers a unique blend of comfort, relaxation and adventure. Each of the 54 rooms is a haven of style and serenity, complete with balcony and private bathroom. In our standard single, double and twin rooms, you will find a simple safari atmosphere with a level of comfort that will not disappoint. These rooms are perfectly situated to view the lodge’s swimming pool, as well as the winding River Nile beyond. Our suites are the perfect accommodation for guests who want a little bit more space to relax. Suites have a living room with sofas where you can use the space to either relax or entertain. For those seeking the ultimate comfort; the Queen’s cottage offers a different world of experience, novelty and exclusivity. The unique architecture compliments the landscaped environment and fantastic views and the grand balcony boasts spectacular views of lush vegetation, rich wildlife, and the famous River Nile. -

Uganda Wildlife Assessment PDFX

UGANDA WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING REPORT ASSESSMENT APRIL 2018 Alessandra Rossi TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Reproduction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organisations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published by: TRAFFIC International David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK © TRAFFIC 2018. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN no: UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Suggested citation: Rossi, A. (2018). Uganda Wildlife Trafficking Assessment. TRAFFIC International, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Front cover photographs and credit: Mountain gorilla Gorilla beringei beringei © Richard Barrett / WWF-UK Tree pangolin Manis tricuspis © John E. Newby / WWF Lion Panthera leo © Shutterstock / Mogens Trolle / WWF-Sweden Leopard Panthera pardus © WWF-US / Jeff Muller Grey Crowned-Crane Balearica regulorum © Martin Harvey / WWF Johnston's three-horned chameleon Trioceros johnstoni © Jgdb500 / Wikipedia Shoebill Balaeniceps rex © Christiaan van der Hoeven / WWF-Netherlands African Elephant Loxodonta africana © WWF / Carlos Drews Head of a hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius © Howard Buffett / WWF-US Design by: Hallie Sacks This report was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S.