A Case Study of Lynn V. Downer and African American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conrad Lynn to Speak at New York Forum

gtiiinimmiimiHi JOHNSON MOVES TO EXPLOIT HEALTH ISSUE THE Medicare As a Vote-Catching Gimmick By M arvel Scholl paign promises” file and dressed kept, so he can toss them around 1964 is a presidential election up in new language. as liberally as necessary, be in year so it is not surprising that Johnson and his Administration dignant, give facts and figures, President Johnson’s message to know exactly how little chance deplore and propose. MILITANT Congress on health and medical there is that any of the legislation He states that our medical sci Published in the Interests of the Working People care should sound like the he proposes has of getting through ence and all its related disciplines thoughtful considerations of a man the legislative maze of “checks are “unexcelled” but — each year Vol. 28 - No. 8 Monday, February 24, 1964 Price 10c and a party deeply concerned over and balances” (committees to thousands of infants die needless the general state of health of the committees, amendments, change, ly; half of the young men un entire nation. It is nothing of the debate and filibuster ad infini qualified for military services are kind. It is a deliberate campaign tum). Words are cheap, campaign rejected for medical reasons; one hoax, dragged out of an old “cam- promises are never meant to be third of all old age public as sistance is spent for medical care; Framed-Up 'Kidnap' Trial most contagious diseases have been conquered yet every year thousands suffer and die from ill nesses fo r w hich there are know n Opens in Monroe, N. -

The Arthur Garfield Hays Civil Liberties Program

THE ARTHUR GARFIELD HAYS CIVIL LIBERTIES PROGRAM ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 August 2020 New York University A private university in the public service School of Law Arthur Garfield Hays Civil Liberties Program 40 Washington Square South New York, New York10012-1099 Co-Directors Professor Emerita Sylvia A. Law Tel: (212) 998-6265 Email:[email protected] Professor Helen Hershkoff Tel: (212) 998-6285 Email: [email protected] THE ARTHUR GARFIELD HAYS CIVIL LIBERTIES PROGRAM ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle. — Martin Luther King, Jr. This Report summarizes the activities of the Hays Program during AY 2019–2020.The year presented extraordinary challenges, as well as important opportunities. Above all, the Hays Program remained steadfast in its central mission: to mentor a new generation of lawyers dedicated to redressing historic inequalities, to resisting injustice, and to protecting democratic institutions. The heart of the Program remained the Fellows and their engagement with lawyers, advocates, and communities through their term-time internships and seminar discussions aimed at defending civil rights and civil liberties. The academic year began with the Trump administration’s continuing assault on the Constitution, from its treatment of immigrants, to its tacit endorsement of racist violence, fueled by the President’s explicit use of federal judicial appointments to narrow civil rights and civil liberties (at this count, an unprecedented two hundred). By March, a global pandemic had caused the Law School, like the rest of the world, to shutter, with the Hays seminar, along with all courses, taught remotely. -

![Roger William Riis Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9097/roger-william-riis-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-399097.webp)

Roger William Riis Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Roger William Riis Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2007 Revised 2010 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms007103 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm81075875 Prepared by Melinda K. Friend Collection Summary Title: Roger William Riis Papers Span Dates: 1903-1990 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1921-1952) ID No.: MSS75875 Creator: Riis, Roger William, b. 1894 Extent: 3,500 items ; 14 containers ; 5.6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Author and editor. Correspondence, diaries, journal, speeches, articles and other writings, subject files, scrapbooks, printed matter, and photographs pertaining to Riis's work as an author and editor. Subjects include consumer fraud, tobacco smoking, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Sherman Antitrust Act. Also includes material pertaining to his service in the U. S. Navy during World War I. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Baldwin, Roger N. (Roger Nash), 1884-1981--Correspondence. Benton, William, 1900-1973--Correspondence. Donner, Robert, -1964--Correspondence. Ernst, Morris L. (Morris Leopold), 1888-1976--Correspondence. Foster, Elizabeth Hipple Riis--Correspondence. Fredericks, Carlton--Correspondence. Hayes, Arthur Garfield--Correspondence. Holmes, John Haynes, 1879-1964--Correspondence. -

54 Doi:10.1162/GREY a 00234 Glenn Ligon. a Small Band, 2015. Neon, Paint, and Metal Support. Installation Views, All the World F

Glenn Ligon. A Small Band , 2015. Neon, paint, and metal support. Installation views, All the World’s Futures, Fifty-Sixth International Venice Biennale, 2015–2016. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist; Luhring Augustine, New York; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; and Thomas Dane Gallery, London. 54 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00234 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00234 by guest on 26 September 2021 How to Hear What Is Not Heard: Glenn Ligon, Steve Reich, and the Audible Past JANET KRAYNAK In 2015, on the occasion of the Venice Biennale, Glenn Ligon prominently installed a large neon sign sculpture atop the façade of the Central Pavilion, one of the buildings in the historic exhibition’s giardini . The visibility of its site, however, stood in contrast to its muted presence and enigmatic message. Crafted from translucent neon and white paint and mounted on a horizontal scaffolding, the work comprised just three detached words (“blues,” “blood,” and “bruise”) that obscured the existing sign (for “la Biennal e” ). Extending an idiosyncratic welcome to visitors, the three words, at any moment, were illu - minated or not, yielding a playful, if nonsensical semiosis. Fragmented from any semantic context, the words were bound together only by the rhythmic sound pattern suggested by their repeating “b’-b’-b’s.” A Small Band , as the work is titled, that silently plays. 1 Ligon has used this strategy—of simultaneous citation and deletion—many times before, most notably in text paintings where he appropriates language only to subject it to processes of distortion and fragmentation, so that words succumb to illegibility. -

Mediating Civil Liberties: Liberal and Civil Libertarian Reactions to Father Coughlin

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2008 Mediating Civil Liberties: Liberal and Civil Libertarian Reactions to Father Coughlin Margaret E. Crilly University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Crilly, Margaret E., "Mediating Civil Liberties: Liberal and Civil Libertarian Reactions to Father Coughlin" (2008). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1166 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Margaret Crilly Mediating Civil Liberties: Liberal and Civil Libertarian Reactions to Father Coughlin Marta Crilly By August 15, 1939, Magistrate Michael A. Ford had had it. Sitting at his bench in the Tombs Court of New York City, faced with a sobbing peddler of Social Justice magazine, he dressed her down with scathing language before revealing her sentence. "I think you are one of the most contemptible individuals ever brought into my court," he stated. "There is no place in this free country for any person who entertains the narrow, bigoted, intolerant ideas you have in your head. You remind me of a witch burner. You belong to the Middle Ages. You don't belong to this modem civilized day of ours .. -

Civil Liberties Outside the Courts Laura M. Weinrib Confidence In

Civil Liberties Outside the Courts Laura M. Weinrib Confidence in liberal legalism as a framework for social change appears to be in a period of decline. In areas ranging from same-sex marriage to racial equality, recent decades have witnessed a resurgence of interest in extrajudicial strategies for advancing civil rights. Debates over popular constitutionalism and calls for constitutional amendment and judicial restraint manifest a growing aversion to the court-centered rights mobilization that dominated legal academia and the liberal imagination for almost half a century.1 Even in the domain of First Amendment protection for free speech—long considered an unassailable case for robust judicial review—the Warren Court consensus has begun to crumble. From the Second World War until the Rehnquist Court, it was an article of faith among activists and academics that a strong First Amendment would preserve a platform for transformative political ideas. In an era when state and federal actors targeted radical agitators, civil rights protestors, and anti-war demonstrators, the Supreme Court was comparatively (if unevenly) friendly to the rights of dissenters. In the 1980s and 1990s, however, a growing chorus of legal scholars described a shift in First Amendment law from the protection of disfavored minorities against state suppression to the insulation of industrial interests against government regulation.2 Over time, such appraisals have become more prevalent and more frenzied. Today, a broad range of legal scholars and cultural critics decry the Court’s “Lochnerization” of the First Amendment: its persistent invalidation of legislative and administrative efforts to temper corporate dominance, and its use of the First Amendment to undermine federal programs or to qualify public sector collective bargaining agreements.3 They lament its 1 The vast literature includes works from a variety of disciplinary and methodological perspectives, including Gerald N. -

Collechon the CHALLENGE HE Struggle for Freedom Today Centers T Around the Activities of the Organized Workers and Farmers

\ \"3 000018 American Civil Liherties Union Our fight is to help secure unrestricted liberty of speech, press and assemblage, as the only sure guarantee of orderly progress. fLORIDA ATLANTIC UNlVElCiin i LiBRARY "It is time enough for the rightful purpose of civil government for its officers to in terfere when principles break out into overt acts against peace and good order." Thos. Jefferson. 138 WEST 13th STREET NEW YORK CITY May, 1921 ~241 SOCIAUST - lABOR COllECHON THE CHALLENGE HE struggle for freedom today centers T around the activities of the organized workers and farmers. Everywhere that strug gle involves the issues of free speech, free press and peaceful assemblage. Everywhere the powers of organized business challenge the right of workers to organize, unionize, strike and picket. The hysterical attacks on "red" propaganda, on radical opinion of all sorts, are in substance a single masked at tack on the revolt of labor and the farmers against industrial tyranny. The hysteria aroused by the war, with its machinery for crushing dissenting opinion, is now directed against the advocates of indus trial freedom. Thirty-five states have passed laws against "criminal syndicalism," crim inal anarchy" or "sedition." Even cities en· act such laws. A wholesale campaign is on to deny the right to strike, by compulsory arbitration and by injunction. The nation wide open-shop crusade is a collossal attempt to destroy all organization of labor. Patrioteering societies, vigilantes, "loyalty leagues," strike-breaking troops or State Con stabularies and the hired gunmen of private corporations contend with zealous local prose cutors in demonstrating their own brands of "law and order." Meetings of workers and farmers are prohibited and broken up, speak ers are mobbed and prosecuted. -

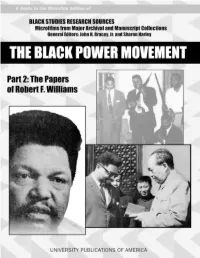

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

A HISTORY of the AMERICAN LEAGUE for PUERTO RICO INDEPENDENCE, 1944-1950 a Thesis by MANUEL A

TRANSNATIONAL FREEDOM MOVEMENTS: A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN LEAGUE FOR PUERTO RICO INDEPENDENCE, 1944-1950 A Thesis by MANUEL ANTONIO GRAJALES, II Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University-Commerce in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2015 TRANSNATIONAL FREEDOM MOVEMENTS: A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN LEAGUE FOR PUERTO RICAN INDEPENDENCE, 1944-1950 A Thesis by MANUEL ANTONIO GRAJALES, II Approved by: Advisor: Jessica Brannon-Wranosky Committee: William F. Kuracina Eugene Mark Moreno Head of Department: Judy A. Ford Dean of the College: Salvatore Attardo Dean of Graduate Studies: Arlene Horne iii Copyright © 2015 Manuel Antonio Grajales II iv ABSTRACT TRANSNATIONAL FREEDOM MOVEMENTS: A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN LEAGUE FOR PUERTO RICO INDEPENDENCE, 1944-1950 Manuel Grajales, MA Texas A&M University-Commerce, 2015 Advisor: Jessica Brannon-Wranosky, PhD A meeting in 1943 between Puerto Rican nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos and a group of U.S. pacifists initiated a relationship built on shared opposition to global imperialism. The association centered on the status of Puerto Rico as a colonial possession of the United States. The nationalists argued that Puerto Rico the island’s definition as a U.S. possession violated their sovereignty and called for aggressive resistance against the United States after attempting to initiate change through the electoral process in 1930. Campos developed his brand of nationalism through collaborations with independence activists from India and Ireland while a student at Harvard. Despite the Puerto Rican nationalists’ rhetorically aggressive stance against U.S. imperialism, conversation occurred with groups of Americans who disapproved of their country’s imperial objective. -

The Inventory of the Conrad Lynn Collection #594

The Inventory of the Conrad Lynn Collection #594 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center LYNN, CONRAD May 1973 Accession N'Wllber: 594 LEGAL FILES, arranged alphabetically. Most contain legal correspon dence, related printed material (newsclippings, etc.) and legal papers (transcripts, appeals, writs, and briefs) 194-0-1972 Box 1, Folder 1 1. '!Abelson, Glenn R." Draft Case, 1968 Folder 2 2. "Aberle, Kathleen" Cor2"espondence from Friend and associates 1963-1964 Folder 3 3. "Acker, Daniel" Draft Case. 1968-1969 Folder 4 4. "Active Selective Service File" 1967-1968 Including: Mungo Ray. CTL. October 16, 1967. Letter denouncing Selective Service system Folder 5 5. "Adams;James" Anthor-Publisher Dispute, 1951-1953 Folder 6 6. "Adams, ifosephine" CL directed her legal affair/a. Miss Adams was the famous "Madame X" of the 1940 1 s. 1958-1959. Folder 7 7. "African Academy of Arts" Landlord-tenant dispute. 1953-1959 Folder 8. 8. "Agett, James" Draft Case. 1970 Folder 9. 9. "Alabama vs. Wilson, Jimmie" Negro facing execution for theft of $1.95. 1958. Folder 10 10. "Albanese, Ralph" Draft Case. 1968-1969 Folder 11 11. "Alenky, Neill" Soldier seeking C. o. discharge from .Anny. 1970-1972 Folder 12 12. "Allen, Robert" Draft Case. 1966 Box 2, Folder 13 13. "Alexander, Rodney" Draft Case. 1968 I - LYNN, CON.RAD. May 197J Page 2 Folder lh 14. "Alleton-Barber" Mother seeking release of son/ from mental institutions 1971-1972 Folder 15. "U.S. vs. Ayalew, et al'! l'Demonstrating Ethiopian students on trial. 1969 Folder 16. 16. "Baehr vs. Baehr" D-vorce Case. 1967-1970 Boxes 3 and 4 17. -

Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case Denise Hill A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Media and Journalism. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Barbara Friedman Lois Boynton Trevy McDonald Earnest Perry Ronald Stephens © 2016 Denise Hill ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Denise Hill: Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case (Under the direction of Dr. Barbara Friedman) This dissertation examines how public relations was used by the Committee to Combat Racial Injustice (CCRI), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), North Carolina Governor Luther Hodges, and the United States Information Agency (USIA) in regards to the 1958 kissing case. The kissing case occurred in Monroe, North Carolina when a group of children were playing, including two African American boys, age nine and eight, and a seven-year-old white girl. During the game, the nine-year-old boy and the girl exchanged a kiss. As a result, the police later arrested both boys and charged them with assaulting and molesting the girl. They were sentenced to a reformatory, with possible release for good behavior at age 21. The CCRI launched a public relations campaign to gain the boys’ freedom, and the NAACP implemented public relations tactics on the boys’ behalf. News of the kissing case spread overseas, drawing unwanted international attention to US racial problems at a time when the country was promoting worldwide democracy. -

Anti-Fascism in a Global Perspective

ANTI-FASCISM IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE Transnational Networks, Exile Communities, and Radical Internationalism Edited by Kasper Braskén, Nigel Copsey and David Featherstone First published 2021 ISBN: 978-1-138-35218-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-35219-3 (pbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-05835-6 (ebk) Chapter 10 ‘Aid the victims of German fascism!’: Transatlantic networks and the rise of anti-Nazism in the USA, 1933–1935 Kasper Braskén (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This OA chapter is funded by the Academy of Finland (project number 309624) 10 ‘AID THE VICTIMS OF GERMAN FASCISM!’ Transatlantic networks and the rise of anti-Nazism in the USA, 1933–1935 Kasper Braskén Anti-fascism became one of the main causes of the American left-liberal milieu during the mid-1930s.1 However, when looking back at the early 1930s, it seems unclear as to how this general awareness initially came about, and what kind of transatlantic exchanges of information and experiences formed the basis of a rising anti-fascist consensus in the US. Research has tended to focus on the latter half of the 1930s, which is mainly concerned with the Communist International’s (Comintern) so-called popular front period. Major themes have included anti- fascist responses to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, the strongly felt soli- darity with the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), or the slow turn from an ‘anti-interventionist’ to an ‘interventionist/internationalist’ position during the Second World War.2 The aim of this chapter is to investigate two communist-led, international organisations that enabled the creation of new transatlantic, anti-fascist solidarity networks only months after Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933.