JMWP 13 Jimoh Shehu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evocative and Persuasive Power of Loaded Words in the Political Discourse on Drug Reform

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenEdition Lexis Journal in English Lexicology 13 | 2019 Lexicon, Sensations, Perceptions and Emotions Conjuring up terror and tears: the evocative and persuasive power of loaded words in the political discourse on drug reform Sarah Bourse Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/3182 DOI: 10.4000/lexis.3182 ISSN: 1951-6215 Publisher Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Electronic reference Sarah Bourse, « Conjuring up terror and tears: the evocative and persuasive power of loaded words in the political discourse on drug reform », Lexis [Online], 13 | 2019, Online since 14 March 2019, connection on 20 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/3182 ; DOI : 10.4000/ lexis.3182 This text was automatically generated on 20 April 2019. Lexis is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Conjuring up terror and tears: the evocative and persuasive power of loaded w... 1 Conjuring up terror and tears: the evocative and persuasive power of loaded words in the political discourse on drug reform Sarah Bourse Introduction 1 In the last few years, the use of the adjective “post-truth” has been emerging in the media to describe the political scene. This concept has gained momentum in the midst of fake allegations during the Brexit vote and the 2016 American presidential election, so much so that The Oxford Dictionary elected it word of the year in 2016. Formerly referring to the lies at the core of political scandals1, the term “post-truth” now describes a situation where the objective facts have far less importance and impact than appeals to emotion and personal belief in order to influence public opinion2. -

Hettie De Villiers, Principal, Does Not Hesitate to Use These Words When

PRESS RELEASE: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SUBJECT: TUKSPORT HIGH SCHOOL SOD TURNING DATE: 06 October 2014 “It’s a dream come true.” Hettie de Villiers, principal, does not hesitate to use these words when she describes her feelings about the fact that, for the first time since its inception 13 years ago, the TuksSport High School will become a proper school next year with its own buildings and own ethos. “I know it is a cliché to say that ‘it’s a dream come true’, but for all of us who are involved with the school, these words say it all. For the past ten years we have been scheming, trying to find out how to go about building a proper school, but it was to no avail because we were unable to get the necessary funding to go ahead. Now, at long last, we have a donor who shares our vision and passion about making a difference in the lives of talented children, not only in sports but on an academic level as well,” De Villiers said. If everything goes according to plan, TuksSport High School will move from the Groenkloof Campus to the LC de Villiers sports grounds in August next year. “One of the plus points of this move will be that the school will be able to develop its own character for the first time. In other words, it will become a school with which both the pupils and teachers can associate themselves. This is very important, because we want the children to feel proud of their school and its achievements.” The TuksSport High School started off in the rugby clubhouse, after which it was moved to an office in the hpc headquarters. -

Nigerian Football System: Examining Meso-Level Practices Against a Global Model for Integrated Development of Mass and Elite Sport I

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Sport and Health Sciences Vol:13, No:9, 2019 Nigerian Football System: Examining Meso-Level Practices against a Global Model for Integrated Development of Mass and Elite Sport I. Derek Kaka’an, P. Smolianov, D. Koh Choon Lian, S. Dion, C. Schoen, J. Norberg football programs and organizations for peace-making and Abstract—This study was designed to examine mass advancement of international relations, tourism, and socio-economic participation and elite football performance in Nigeria with reference development. Accurate reporting of the sports programs from the to advance international football management practices. Over 200 media should be encouraged through staff training for better sources of literature on sport delivery systems were analyzed to awareness of various events. The systematic integration of these construct a globally applicable model of elite football integrated with meso-level practices into the balanced development of mass and mass participation, comprising of the following three levels: macro- high-performance football will contribute to international sport (socio-economic, cultural, legislative, and organizational), meso- success as well as national health, education, and social harmony. (infrastructures, personnel, and services enabling sport programs) and micro-level (operations, processes, and methodologies for Keywords—Football, high performance, mass participation, development of individual athletes). The model has received Nigeria, sport development. scholarly validation and showed to be a framework for program analysis that is not culturally bound. The Smolianov and Zakus I. INTRODUCTION model has been employed for further understanding of sport systems such as US soccer, US Rugby, swimming, tennis, and volleyball as N Nigeria, there has been an increase in football well as Russian and Dutch swimming. -

Maternal Activism

1 Biography as Philosophy The Power of Personal Example for Transformative Theory As I have written this book, my kids have always been present in some way. Sometimes, they are literally present because they are beside me playing, asking questions, wanting my attention. Other times, they are present in the background of my consciousness because I’m thinking about the world they live in and the kind of world I want them to live in. Our life together is probably familiar to many U.S. middle-class women: I work full-time, the kids go to school full time, and our evenings and weekends are filled with a range of activities with which we are each involved. We stay busy with our individual activities, but we also come together for dinner most nights, we go on family outings, and we enjoy our time together. As much time as I do spend with my kids, I constantly feel guilty for not doing enough with them since I also spend significant time preparing for classes, grading, researching, and writing while I’m with them. Along with many other women, I feel the pressure of trying and failing to balance mothering and a career. Although I feel as though I could be a better mother and a bet- ter academic, I also have to concede that I lead a privileged life as a woman and mother. Mothers around the world would love to have the luxury of providing for their children’s physical and mental well-being. In the Ivory Coast and Ghana, children are used as slave labor to harvest cocoa beans for chocolate (Bitter Truth; “FLA Highlights”; Hawksley; The Food Empowerment Project). -

Imperialism and the 1999 Women's World Cup

IMPERIALISM AND THE 1999 WOMEN’S WORLD CUP: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES AND NIGERIAN NATIONAL TEAMS IN THE U.S. MEDIA by Michele Canning A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida April 2009 Copyright by Michele Canning 2009 ii ABSTRACT Author: Michele Canning Title: Imperialism and the 1999 Women’s World Cup: Representations of the United States and Nigerian National Teams in the U.S. Media Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Josephine-Beoku-Betts Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2009 This research examines the U.S. media during the 1999 Women’s World Cup from a feminist postcolonial standpoint. This research adds to current feminist scholarship on women and sports by de-centering the global North in its discourse. It reveals the bias of the media through the representation of the United States National Team as a universal “woman” athlete and the standard for international women’s soccer. It further argues that, as a result, the Nigerian National Team was cast in simplistic stereotypes of race, class, ethnicity, and nation, which were often also appropriated and commodified. I emphasize that the Nigerian National Team resisted this construction and fought to secure their position in the global soccer landscape. I conclude that these biased representations, which did not fairly depict or value the contributions of diverse competing teams, were primarily employed to promote and sell the event to a predominantly white middle-class American audience. -

Political Discourse in Football Coverage – the Cases of Côte D’Ivoire and Ghana

GIGA Research Unit: Institute of African Affairs ___________________________ Political Discourse in Football Coverage – The Cases of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana Andreas Mehler N° 27 August 2006 www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers GIGA-WP-27/2006 GIGA Working Papers Edited by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien. The Working Paper Series serves to disseminate the research results of work in progress prior to publication to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. Inclusion of a paper in the Working Paper Series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. Copyright remains with the authors. When Working Papers are eventually accepted by or published in a journal or book, the correct citation reference and, if possible, the corresponding link will then be included in the Working Papers website at: www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers. GIGA research unit responsible for this issue: Research Unit: Institute of African Affairs. Editor of the GIGA Working Paper Series: Bert Hoffmann <[email protected]> Copyright for this issue: © Andreas Mehler Editorial assistant and production: Verena Kohler All GIGA Working Papers are available online and free of charge at the website: www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers. Working Papers can also be ordered in print. For production and mailing a cover fee of € 5 is charged. For orders or any requests please contact: e-mail: [email protected] phone: ++49 (0)40 - 428 25 548 GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien Neuer Jungfernstieg 21 20354 Hamburg Germany E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.giga-hamburg.de GIGA-WP-27/2006 Political Discourse in Football Coverage – The Cases of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana Abstract Football coverage in newspapers is both an arena for and a mirror of political discourse within a society. -

Angel Or Devil? a Privacy Study of Mobile Parental Control Apps

Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies ..; .. (..):1–22 Álvaro Feal*, Paolo Calciati, Narseo Vallina-Rodriguez, Carmela Troncoso, and Alessandra Gorla Angel or Devil? A Privacy Study of Mobile Parental Control Apps Abstract: Android parental control applications are 1 Introduction used by parents to monitor and limit their children’s mobile behaviour (e.g., mobile apps usage, web brows- The dependency of society on mobile services to per- ing, calling, and texting). In order to offer this service, form daily activities has drastically increased in the last parental control apps require privileged access to sys- decade [81]. Children are no exception to this trend. Just tem resources and access to sensitive data. This may in the UK, 47% of children between 8 and 11 years of age significantly reduce the dangers associated with kids’ have their own tablet, and 35% own a smartphone [65]. online activities, but it raises important privacy con- Unfortunately, the Internet is home for a vast amount cerns. These concerns have so far been overlooked by of content potentially harmful for children, such as un- organizations providing recommendations regarding the censored sexual imagery [20], violent content [91], and use of parental control applications to the public. strong language [51], which is easily accessible to minors. We conduct the first in-depth study of the Android Furthermore, children may (unawarely) expose sensitive parental control app’s ecosystem from a privacy and data online that could eventually fall in the hands of regulatory point of view. We exhaustively study 46 apps predators [2], or that could trigger conflicts with their from 43 developers which have a combined 20M installs peers [30]. -

Nomineees 181129

African Player of the year 1. Abdelmoumene Djabou (Algeria & ES Setif) 2. Ahmed Gomaa (Egypt & El Masry) 3. Ahmed Musa (Nigeria & Al-Nassr ) 4. Alex Iwobi (Nigeria & Arsenal) 5. Andre Onana (Cameroon & Ajax) 6. Anis Badri (Tunisia & Esperance) 7. Ayoub El Kaabi (Morocco & Hebei China Fortune) 8. Ben Malango (DR Congo & TP Mazembe) 9. Denis Onyango (Uganda & Mamelodi Sundowns) 10. Fanev Andriatsima (Madagascar & Clermont Foot) 11. Franck Kom (Cameroon & Esperance) 12. Jacinto Muondo Dala ‘Gelson’ (Angola & Primeiro de Agosto) 13. Hakim Ziyech (Morocco & Ajax) 14. Idrissa Gueye (Senegal & Everton) 15. Ismail Haddad (Morocco & Wydad Athletic Club) 16. Jean-Marc Makusu Mundele (DR Congo & AS Vita) 17. Kalidou Koulibaly (Senegal & Napoli) 18. Mahmoud Benhalib (Morocco & Raja Club Athletic) 19. Mehdi Benatia (Morocco & Juventus) 20. Mohamed Salah (Egypt & Liverpool) 21. Moussa Marega (Mali & Porto) 22. Naby Keita (Guinea & Liverpool) 23. Odion Ighalo (Nigeria & Changchun Yatai, Nigeria) 24. Percy Tau (South Africa & Union Saint-Gilloise) 25. Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang (Gabon & Arsenal) 26. Riyad Mahrez (Algeria & Manchester City) 27. Sadio Mane (Senegal & Liverpool) 28. Taha Khenissi (Tunisia & Esperance) 29. Thomas Partey (Ghana & Atletico Madrid) 30. Wahbi Khazri (Tunisia & Saint-Étienne) 31. Walid Soliman (Egypt & Ahly) 32. Wilfried Zaha (Cote d’Ivoire & Crystal Palace) 33. Yacine Brahimi (Algeria & Porto) 34. Youcef Belaili (Algeria & Esperance) CONFEDERATION AFRICAINE DE FOOTBALL 3 Abdel Khalek Tharwat Street, El Hay El Motamayez, P.O. Box 23 6th October City, Egypt - Tel.: +202 38247272/ Fax : +202 38247274 – [email protected] Women’s African player of the year 1. Abdulai Mukarama (Ghana & Northern Ladies) 2. Asisat Oshoala (Nigeria & Dilian Quanjian) 3. Bassira Toure (Mali & AS Mande) 4. -

SAFA Chairperson: Portfolio Committee on Sport and Recreation

SAFA Chairperson: Portfolio Committee on Sport and Recreation Cape Town, 1 November 2019 SAFA A BRIEF BACKGROUND SAFA Governance SAFA GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE SAFA GENERAL COUNCIL 52 Regional Members, 9 Associate Members, 1 Special Member (NSL) SAFA NEC STANDING SAFA COMMITTEES SECRETARIAT DIVISIONS • Football • Football Business • Corporate Services • Legal, Compliance, Membership • Financial Platform SAFA ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE FOOTBALL FOOTBALL BUSINESS CORPORATE SERVICES •Referees •IT •International Affairs •Coaching •Communications •Facilities & Logistics •Nat’l Teams •Commercial •National Technical Ctr •Women’s Football •Events •Safety & Security •Youth Development •Competitions / Leagues •2023 Bid •Futsal •Beach Soccer FINANCE LEGAL, COMPLIANCE, •Procurement MEMBERSHIP •Internal Audit •Financial Platform • Legal / Litigation •Asset Management • Compliance •Fleet Management • Membership •Human Resources • Club Licensing • Integrity SAFA Governance Instruments SAFA STATUTES RULES • National • Competitions • Regional Standard Statutes • Meetings • LFA Statutes • Application of the Statutes • PEC Standard Statutes REGULATIONS -Disciplinary Code -Ethics, Fair Play & Corruption -Electoral Code -Hosting Int’l Matches in SA -Intermediaries Regulations -Club Licensing -Academies Regulations -Referees Code of Conduct -Standing Orders for Meetings -Communications Policy -Player Status & Transfer Regulations ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES • Financial • HR • ICT • Other operational requirements Master Licensor for Football in SA 1. Members (Provincial, -

The Theory of Dyadic Morality: © 2017 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc

PSRXXX10.1177/1088868317698288Personality and Social Psychology ReviewSchein and Gray 698288research-article2017 Article Personality and Social Psychology Review 1 –39 The Theory of Dyadic Morality: © 2017 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc. Reprints and permissions: Reinventing Moral Judgment by sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868317698288 10.1177/1088868317698288 Redefining Harm pspr.sagepub.com Chelsea Schein1 and Kurt Gray1 Abstract The nature of harm—and therefore moral judgment—may be misunderstood. Rather than an objective matter of reason, we argue that harm should be redefined as an intuitively perceived continuum. This redefinition provides a new understanding of moral content and mechanism—the constructionist Theory of Dyadic Morality (TDM). TDM suggests that acts are condemned proportional to three elements: norm violations, negative affect, and—importantly—perceived harm. This harm is dyadic, involving an intentional agent causing damage to a vulnerable patient (A→P). TDM predicts causal links both from harm to immorality (dyadic comparison) and from immorality to harm (dyadic completion). Together, these two processes make the “dyadic loop,” explaining moral acquisition and polarization. TDM argues against intuitive harmless wrongs and modular “foundations,” but embraces moral pluralism through varieties of values and the flexibility of perceived harm. Dyadic morality impacts understandings of moral character, moral emotion, and political/cultural differences, and provides research guidelines for moral psychology. Keywords morality, social cognition, judgment/decision making, moral foundations theory, values The man intentionally gished the little girl, who cried. Kellogg, 1890, p. 233). The creator of Kellogg’s cereal Gish is not a real word, but when people read this sentence, was claiming that masturbation was morally wrong they automatically judge the man to be doing something because of the harm it caused. -

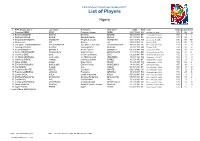

List of Players

FIFA Women's World Cup Canada 2015™ List of Players Nigeria # FIFA Display Name Last Name First Name Shirt Name DOB POS Club Height Caps Goals 1 Precious DEDE DEDE Precious Uzoaru DEDE 18.01.1980 GK Ibom Queens (NGA) 170 96 0 2 Blessing EDOHO EDOHO Blessing EDOHO 05.09.1992 DF Pelican Stars FC (NGA) 160 4 1 3 Osinachi OHALE OHALE Osinachi Marvis OHALE 21.12.1991 DF Rivers Angels FC (NGA) 173 24 1 4 Perpetua NKWOCHA NKWOCHA Perpetua Ijeoma NKWOCHA 03.01.1976 FW Clemensnäs IF (SWE) 180 98 80 5 Onome EBI EBI Onome EBI 08.05.1983 DF FC Minsk (BLR) 175 48 0 6 Josephine CHUKWUNONYE CHUKWUNONYE Josephine Chiwendu CHUKWUNONYE 19.03.1992 DF Rivers Angels FC (NGA) 173 22 0 7 Ukpong SUNDAY SUNDAY Ukpong Esther SUNDAY 13.03.1992 FW FC Minsk (BLR) 158 23 5 8 Asisat OSHOALA OSHOALA Asisat Lamina OSHOALA 09.10.1994 FW Liverpool LFC (ENG) 169 14 10 9 Desire OPARANOZIE OPARANOZIE Ugochi Desire OPARANOZIE 17.12.1993 FW En Avant Guingamp (FRA) 165 32 22 10 Courtney DIKE DIKE Courtney Ozioma DIKE 03.02.1995 FW Oklahoma State Univ. (USA) 156 0 0 11 Ini-Abasi UMOTONG UMOTONG Ini-Abasi Anefiok UMOTONG 15.05.1994 FW Portsmouth LFC (ENG) 165 0 0 12 Halimatu AYINDE AYINDE Halimatu Ibrahim AYINDE 16.05.1995 MF Delta Queens FC (NGA) 165 9 0 13 Ngozi OKOBI OKOBI Ngozi Sonia OKOBI 14.12.1993 FW Delta Queens FC (NGA) 165 22 2 14 Evelyn NWABUOKU NWABUOKU Evelyn Chiedu NWABUOKU 14.11.1985 MF BIIK Kazygurt (KAZ) 167 39 3 15 Ugo NJOKU NJOKU Ugo NJOKU 27.11.1994 DF Rivers Angels FC (NGA) 172 6 0 16 Ibubeleye WHYTE WHYTE Ibubeleye WHYTE 09.01.1992 GK Rivers Angels FC (NGA) -

Tactical Line-Up Nigeria - France

FIFA Women's World Cup France 2019™ Group A Tactical Line-up Nigeria - France # 25 17 JUN 2019 21:00 Rennes / Roazhon Park / FRA Nigeria (NGA) Shirt: light green/white Shorts: white Socks: light green/white # Name Pos 16 Chiamaka NNADOZIE GK 3 Osinachi OHALE DF 4 Ngozi EBERE DF 5 Onome EBI DF 8 Asisat OSHOALA FW 9 Desire OPARANOZIE (C) X FW 10 Rita CHIKWELU X MF 13 Ngozi OKOBI MF 17 Francisca ORDEGA X FW 18 Halimatu AYINDE MF 20 Chidinma OKEKE DF Substitutes 1 Tochukwu OLUEHI GK 2 Amarachi OKORONKWO MF 6 Evelyn NWABUOKU MF 7 Anam IMO FW 11 Chinaza UCHENDU MF 12 Uchenna KANU FW 15 Rasheedat AJIBADE MF Matches played 19 Chinwendu IHEZUO FW 08 Jun NOR - NGA 3 : 0 ( 3 : 0 ) 21 Alaba JONATHAN GK 12 Jun NGA - KOR 2 : 0 ( 1 : 0 ) 22 Alice OGEBE FW 23 Ogonna CHUKWUDI MF 14 Faith MICHAEL A DF Coach Thomas DENNERBY (SWE) France (FRA) Shirt: navy blue Shorts: white Socks: red # Name Pos 16 Sarah BOUHADDI GK 2 Eve PERISSET DF 3 Wendie RENARD DF 6 Amandine HENRY (C) MF 10 Amel MAJRI DF 13 Valerie GAUVIN FW 14 Charlotte BILBAULT MF 17 Gaetane THINEY MF 18 Viviane ASSEYI FW 19 Griedge MBOCK BATHY DF 20 Delphine CASCARINO FW Substitutes 1 Solene DURAND GK 4 Marion TORRENT DF 5 Aissatou TOUNKARA DF 7 Sakina KARCHAOUI DF 8 Grace GEYORO MF 9 Eugenie LE SOMMER X FW 11 Kadidiatou DIANI FW Matches played 12 Emelyne LAURENT FW 07 Jun FRA - KOR 4 : 0 ( 3 : 0 ) 15 Elise BUSSAGLIA MF 12 Jun FRA - NOR 2 : 1 ( 0 : 0 ) 21 Pauline PEYRAUD-MAGNIN GK 22 Julie DEBEVER DF 23 Maeva CLEMARON MF Coach Corinne DIACRE (FRA) GK: Goalkeeper A: Absent W: Win GD: Goal difference VAR: Video Assistant Referee DF: Defender N: Not eligible to play D: Drawn Pts: Points AVAR 1: Assistant VAR MF: Midfielder I: Injured L: Lost AVAR 2: Offside VAR FW: Forward X: Misses next match if booked GF: Goals for C: Captain MP: Matches played GA: Goals against MON 17 JUN 2019 20:04 CET / 20:04 Local time - Version 1 22°C / 71°F Hum.: 54% Page 1 / 1.