Rice University Pre-AP High School English For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Guided Practice in Argument Analysis And

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2020 The Impact of Guided Practice in Argument Analysis and Composition via Computer-Assisted Argument Mapping Software on Students’ Ability to Analyze and Compose Evidence-Based Arguments Donna Lorain Grant Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Grant, D. L.(2020). The Impact of Guided Practice in Argument Analysis and Composition via Computer- Assisted Argument Mapping Software on Students’ Ability to Analyze and Compose Evidence-Based Arguments. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/6079 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF GUIDED PRACTICE IN ARGUMENT ANALYSIS AND COMPOSITION VIA COMPUTER -ASSISTED ARGUMENT MAPPING SOFTWARE ON STUDENTS’ ABILITY TO ANALYZE AND COMPOSE EVIDENCE -BASED ARGUMENTS by Donna Lorain Grant Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina—Upstate, 2000 Master of Education Converse College, 2007 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Education in Curriculum and Instruction College of Education University of South Carolina 2020 Accepted by: Rhonda Jeffries , Major Professor Yasha Becton, Committee Member Leigh D’Amico, Committee Member Kamania Wynter-Hoyte, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Donna Lorain Grant, 2020 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ who made me for a purpose and graced me with the ability to fulfill it To my father, Donald B. -

12Th, ' .Developmental St

r . DOCUMENT RESUME , - .ED.176. 292 , CS 205 131 AUTHOR .Millere*Susan 'TITLE Rhetorical Maturity: Definition and Development. PUB DATE. May.79 NOTE. 23p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Council of Teachers tf English (12th, ' Ottawa, Canada, May 8-11, 1979) EDRS ?RICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS /.College Freshmen; *Conposition (Literary) ; / .Developmental Stages;'*Educational Theoried; Higher Education; *Moral Develcpment; Persuasive Disqourse; ,*Rhetoric; *Student Developnent; ItNriting Skills IDENTIFIER'S. *Kohlberg (Lawrence) . ABSTRACT Lawrence Kohlterg4s stageS of moral development, when appliedito theories'of teaching Ccmpositien,_support any method or material that refers to, the age 4nd prior experience o4 the writer ,and the newness of th.e task.the writer is attempting. Rhetorical development and maturation, in%the ability to write and argue . persuasively are partly 'conc'eptual and partly related to the ability .to "decanter." College freshmin writers' responses to A classic moral 'dilemma ptoblen all stayed between Kohlberg's Conventional stages 3 and 4. The content.of their papers end its relationshiy ic Kohlberg!s. .'stagea'show that the movement.trom egocentric tc explanatory to persuasive'discourse-is evmovement from the writer's astumption of union with an audiehce to the writer's recognitiot cf ano'ther as an msudience and finally to the mriter0s.analysis of a distant4 oirunfaniliaT, universalized series.of valued as an audience.. complete Sample of class reiponses referred.to is appetded.) (AEA) I. sl 4 14341*************41****************************************************** * 200roductions supplied by.EDES are th,e best that can be aade., * from the original document. 4 , * 1 c. U.S. OSPAISTIAINT Of IIIIALTN. -

Writing Real World

WRITING FOR A REAL WORLD Writing for a Real World 2010–2011 A multidisciplinary anthology by USF students PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO DEPARTMENT OF RHETORIC AND LANGUAGE www.usfca.edu/wrw Writing for a Real World (WRW) is published annually by the Department of Rhetoric and Language, College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco. WRW is governed by the Rhetoric and Language Publication Committee, chaired by David Holler. Members are: Brian Komei Dempster, Michelle LaVigne, Michael Rozendal, and David Ryan. Writing for a Real World: 9th edition © 2011 The opinions stated herein are those of the authors. Authors retain copyright for their individual work. Essays include bibliographical references. The format and practice of documenting sources are determined by each writer. Writers are responsible for validating and citing their research. Cover image courtesy of Marti S. This photograph was taken in Havana, Cuba. Printer: DeHarts Printing, San Jose, Calif. To get involved as a referee, serve on the publication committee, obtain back print issues, or to learn about submitting to WRW, please contact David Holler <[email protected]>. Back issues are now available online via Gleeson Library’s Digital Collections. For all other inquiries: Writing for a Real World, University of San Francisco, Kalmanovitz Hall, Rm. 202, 2130 Fulton Street, San Francisco, CA, 94117. Fair Use Statement: Writing for a Real World is an educational journal whose mission is to showcase the best undergraduate writing at the University of San Francisco. Student work often contextualizes and recontextualizes the work of others within the scope of course- related assignments. -

Revisiting Listening Rhetoric Through Mindfulness, Empathy, and Non-Violent Communication

The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning Volume 23 Winter 2017-2018 Article 10 1-1-2018 Rhetorics of Reflection: Revisiting Listening Rhetoric through Mindfulness, Empathy, and Non-violent Communication Renea Frey Xavier University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl Recommended Citation Frey, Renea (2018) "Rhetorics of Reflection: Revisiting Listening Rhetoric through Mindfulness, Empathy, and Non-violent Communication," The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning: Vol. 23 , Article 10. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl/vol23/iss1/10 This Special Section is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl. JAEPL, Vol. 23, Winter 2017–2018 Rhetorics of Reflection: Revisiting Listening Rhetoric through Mindfulness, Empathy, and Nonviolent Communication Renea Frey ayne Booth described “Listening Rhetoric” as a rhetorical stance based in eth- Wics, connection, and understanding—which he termed rhetorology—and he saw it as as imperative in a world filled with potential global conflict and crisis. Krista Ratcliffe, too, has called for developing deeper listening skills as a means of generating understanding across lines of race and gender, and she describes rhetorical listening “as a trope for interpretive invention…[which]… signifies a stance of openness that a person may choose to assume in relation to any person, text, or culture” (17). -

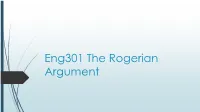

Rogerian Argument

RHETORIC Rogerian Argument Traditional Argument Rogerian Argument Basic Strategy Writer states the claim and Writer states the opponent’s gives reasons to prove it. claim and points out what Writer refutes the opponent is sound about the reasons by showing what is wrong used to prove it. or invalid. Ethos Writer builds own character Writer builds opponent’s (ethos) by citing past character, perhaps at the experience and expertise. expense of his or her own. Logos Writer uses logic (all the Writer proceeds in an proofs) as tools for explanatory fashion to presenting a case and analyze the conditions refuting the opponent’s under which the position of case. either side is valid. Pathos Writer uses emotional Writer uses descriptive, language to strengthen the dispassionate language to claim. cool emotions on both sides. Goal Writer tries to change Writer creates cooperation, opponent’s mind and the possibility that both thereby win the argument. sides might change, and a mutually advantageous outcome. Use of Argumentative Writer draws on the Writer throws out Techniques conventional structures and conventional structures and techniques taught in techniques because they argument papers. may be threatening. Writer focuses, instead, on connecting empathetically. Questions to Consider Before Drafting: 1. Who is my intended audience? Is it the person I am directly writing to or some imagined third party? 2. What do I know about my intended audience? 3. What do my readers know about the subject at hand? 4. Why do they believe what they do? Why do they think and feel that my position is wrong? 5. -

Mindfulness, Buddhism, and Rogerian Argument

The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning Volume 11 Winter 2005-2006 Article 8 2005 Mindfulness, Buddhism, and Rogerian Argument Alexandria Peary Daniel Webster College Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl Part of the Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Other Education Commons, Special Education and Teaching Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Peary, Alexandria (2005) "Mindfulness, Buddhism, and Rogerian Argument," The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning: Vol. 11 , Article 8. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl/vol11/iss1/8 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl. Mindfulness, Buddhism, and Rogerian Argument Cover Page Footnote Alexandria Peary is Associate Professor of Humanities and Director of Writing at Daniel Webster College. This essay is available in The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl/vol11/iss1/8 64 JAEPL, Vol. 11, Winter 2005–2006 Mindfulness, Buddhism, and Rogerian Argument Alexandria Peary In many American universities, there is a course called Communication Skills. -

Teaching Argumentation (PDF)

Teaching Argumentation Overview Teaching students “how to write” can seem like a daunting task on top of teaching them course content. On the other hand, if you teach students how to argue, you can leverage writing to help students engage more deeply with course content. In Andrea Lunsford and John Ruszkiewicz’s widely-adopted textbook, Everything’s An Argument, they lay out perhaps the clearest definition of argument in the university setting we’ve seen, and it’s worth quoting in full: …[A]n academic argument is simply one that is held to the standards of a professional field or discipline, such as psychology, engineering, political science, or English. It is an argument presented to knowledgeable people by writers who are striving to make an honest case that is based on the best information and research available, with all of its sources carefully documented. (15) Thus, when you teach argument, you’re teaching students how to think, and how to communicate their thinking, about the course material—the “meat” of your field—while also teaching them how to write. Arguments take a nearly endless variety of shapes, but every argument needs claims and evidence—whether explicit or implicit—in order to work. Many rhetoricians break down the building blocks even further, including reasons as well as evidence, while some consider reasons and evidence part of the same element. Claims: What you are arguing. A thesis statement, then, is the main claim of an argument. All other claims used to build up to that main claim are supporting, or sub-claims. -

Argument and Common Ground: Scholarly Research Meets the Common Core State Standards

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jillian Clark for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 6, 2014. Title: Argument and Common Ground: Scholarly Research Meets the Common Core State Standards Abstract approved: Vicki Tolar Burton This thesis examines the recent history of the teaching of argument and its implications in the face of new writing standards being implemented in K-12 classrooms under the Common Core State Standards. The new educational policies will shift the focus of writing instruction onto argument writing as part of students’ “college readiness.” In a survey and analysis of the argument scholarship in the National Council of Teachers of English’s (NCTE) premier journals on the teaching of writing, College English and College Composition and Communication, I demonstrate the clear trend in college argument scholarship away from initially hostile, two-sided debates. Scholarship in these journals instead advocates for process-oriented argument pedagogies that account for multiple voices, working towards arguments of cooperation and skills that can be transferred out of the classroom and into real-world problem-solving scenarios. Through close readings of the Common Core State Standards for Writing in Grades 11-12 and the NCTE’s college-readiness document, the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing, I argue that teachers of argument can honor the commitment to cooperation present in argument scholarship while meeting the state standards by using the Framework as a guide to pedagogy, which is not dictated by the standards. This thesis challenges the assumptions of opposition between policy and pedagogy in the teaching of argument by seeking their common ground. -

{PDF} Writing Arguments a Rhetoric with Readings, Concise Edition

WRITING ARGUMENTS A RHETORIC WITH READINGS, CONCISE EDITION, MLA UPDATE EDITION 7TH EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John D Ramage | 9780134586496 | | | | | Writing Arguments A Rhetoric with Readings, Concise Edition, MLA Update Edition 7th edition PDF Book Not yet available. If You're an Educator Download instructor resources Additional order info. John D. The Persuasive Use of Evidence. Appealing to a Resistant Audience: Dialogic Argument. Sign Up Already have an access code? An American journalist argues for an increased federally mandated minimum wage combined with government policies to promote job growth and ensure a stable safety net for the poor. We explore new places, vistas, and emotions through the words that authors have written in the book. She has a B. Username Password Forgot your username or password? Expressing Reasons in Because Clauses. If You're a Student. Questioning and Critiquing a Proposal Argument. Skip to main content. Theoretical approaches to argument challenge students to think critically and logically. He has published numerous articles on writing and writing-across-the-curriculum as well as on literary subjects including Shakespeare and Spenser. Comprehensive coverage of research emphasizes an inquiry approach, discusses the importance of evaluating sources, explains how to incorporate sources to support an argument, illustrates where citation information is found in common types of sources, and provides up-to-date MLA and APA citation guidelines. And with knowledge comes confidence. You have successfully signed out and will be required to sign back in should you need to download more resources. New visual examples throughout the text. More annotated student model essays are provided. -

Eng301 the Rogerian Argument Argument and Conflict

Eng301 The Rogerian Argument Argument and Conflict As we have seen in recent political campaigns, argument and conflict seem to be inseparable. History shows us the truth of this, yet history also shows the precedent of successful arguments without conflict. Among the key characteristics of effective arguments are the ability to seek out, understand, and present the views of those who disagree with us. This may include the willingness to understand and establish common ground, and the ability to consider and present better solutions or compromise. In doing so we recognize that arguments are not “black or white”, “right or wrong”, “for or against.” In reality arguments are layered, often subtle, and dependent on direct and indirect assumptions. Carl Rogers In the first half of the 20th century psychotherapist Carl Rogers began to argue for considering communication in terms of avoiding judgement and evaluation. “I would like to propose, as an hypothesis for consideration, that the major barrier to mutual impersonal communication is our very natural tendency to judge, to evaluate, to approve or disapprove, the statement of the other person, or the other group” (76). Rogers believed the ability to listen was central to effective communication, especially in high stakes communication, such as in communicating with a person with a mental disability. However, Rogers saw this as a societal or cultural process rather than one based in illness. He also understood the challenges inherent in trying to avoid or mitigate the above barriers. Carl Rogers Continued “The next time you get into an argument with your wife, or your friend, or with a small group of friends, just stop the discussion for a moment and for an experiment, institute this rule. -

Working Alliances: the Implications of Person- Centered Theory for Student-Teacher Relationships and Learning

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2018 WORKING ALLIANCES: THE IMPLICATIONS OF PERSON- CENTERED THEORY FOR STUDENT-TEACHER RELATIONSHIPS AND LEARNING Adam Parker Cogbill University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Cogbill, Adam Parker, "WORKING ALLIANCES: THE IMPLICATIONS OF PERSON-CENTERED THEORY FOR STUDENT-TEACHER RELATIONSHIPS AND LEARNING" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 2388. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2388 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORKING ALLIANCES: THE IMPLICATIONS OF PERSON-CENTERED THEORY FOR STUDENT-TEACHER RELATIONSHIPS AND LEARNING BY ADAM COGBILL BA, Franklin and Marshall College, 2007 MFA, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 2012 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May, 2018 ii This thesis/dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by: Thesis/Dissertation Director, Dr. Christina Ortmeier-Hooper, Associate Professor of English Dr. Cristy Beemer, Associate Professor of English Dr. Alecia Magnifico, Assistant Professor of English Dr. Loan Phan, Associate Professor of Education Dr. Bronwyn Williams, Professor of English, University of Louisville On April 2, 1018 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

To Read an Introduction to Political Science By

An Introduction to Political Science Jonathon York Introduction This project is intended to constitute an Introduction to the formal study of politics and political science, being a variation of what I wish I had when I first entered the discipline. All institutions of higher education tend to focus on a specific subfield or set of subfields, not necessarily intentionally, but over time these institutions produce what can best be described as a disciplinary orthodoxy, distorting the student’s vision of the discipline as a whole such that he or she may conceive of the whole of the discipline as constituting merely what the professors parade in front of their classrooms, in their textbooks, and in their supplemental materials. Knowing this to be the case it is my intention to present as broad a picture of the discipline as I can manage, in order that I may avoid the potential damage of the prejudices ingrained by a too-narrow view of the discipline as a whole. My own exposure to the discipline of political study was largely hampered by the blinders of those self-described students of politics at the University of Dallas who followed in the footsteps of the students of Leo Strauss, who on one hand insisted that in order to understand a thinker one must, if at all possible, closely read everything that thinker ever wrote (a laudable though difficult task for many)1, but on the other openly derided other methodological currents in the discipline, especially those that forsook the political philosophical tradition of the field and instead sought to adapt or emulate the quantitative methods of the natural sciences.