Evaluating Cost, Privacy, and Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

1 1 Williamson BC Chang Professor of Law University of Hawai'i William S. Richardson School of Law Education

1 Williamson B.C. Chang Professor of Law University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law Education: 1972 A.B. Princeton University [Graduated in three years] Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs Certificate in East Asian Affairs Thesis: “The May 7th Cadre School and the Chinese Cultural Revolution” 1975 J.D. University of California, Berkeley Associate Editor, California Law Review Associate Editor, Ecology Law Quarterly Clerkship: Judge Dick Yin Wong, United States District Court for the District of Hawai‘i 1975-76 Teaching: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor and Professor of Law, University of Hawai‘i 1976 to Present Courses: Corporations, Business Associations, Corporate Taxation, Conflict of Laws, Legal Aspects of Water Rights, Jurisprudence, Legal Methods, Legal Practice, Securities Regulation, Law of Indigenous Peoples and Native Hawaiian Policy and Governance Visiting Professor: Hiroshima University, 1987 University of Wisconsin, 1989, University of Western Australia 1989, University of San Francisco, 1993 Associations, Affiliations and Awards: 2017 Native Hawaiian Patriot of the Year awarded by the Koani Foundation. Outstanding Native Hawaiian for 2014, presented by Native Hawaiian Student Association, William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawaii at Manoa September 12, 2014 Senior Fulbright Scholar, University of Western Australia 1989 Editor and Member, American Society of Comparative Law (Board Member 1990) Trustee, Law and Society Association 1993 1 2 Senior Legislative Counsel, United States Select Committee on Indian Affairs, Chairman of Committee, Senator Daniel K. Inouye 1990 Reporter, Advisory Commission on Water Resources (Drafted Hawai‘i State Water Code) 1984-1986 Special Deputy Attorney General, State of Hawai‘i 1978-1984 (Represented State of Hawai‘i and Chief Justice William S. -

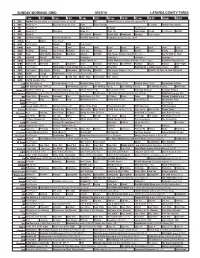

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/23/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 Am 7:30 8 Am 8:30 9 Am 9:30 10 Am 10:30 11 Am 11:30 12 Pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Giants Vs

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/23/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Giants vs. Los Angeles Rams. (6:30) (N) NFL Football Raiders at Jacksonville Jaguars. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Figure Skating F1 Count Formula One Racing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Regional Coverage. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Rick Steves’ Europe Travel Skills (TVG) Å Age Fix With Dr. Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Home Alone 2: Lost in New York ›› (1992) (PG) Zona NBA Next Day Air › (2009) Donald Faison. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 24, 2021 FULL THROTTLE FUN WITH

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 24, 2021 Download Photo Here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/19TZIuaQ_7S1rquLqyIBP0Lsqj89G3wRp/view?usp=sharing FULL THROTTLE FUN WITH FRIENDS IN THE NEW ORIGINAL SERIES KEVIN HART’S MUSCLE CAR CREW, STREAMING JULY 2 ON THE MOTORTREND APP --The Series is Produced by HartBeat Productions and Big Breakfast-- (Los Angeles) – When the gearhead bug bites it doesn’t let go. After a grueling year-long comedy tour Kevin Hart surprised his crew, affectionately named The Plastic Cup Boyz, with classic cars for each one of them. As brand-new muscle car devotees the guys have fallen deeply for classic car culture. In fact, they’re on a mission to launch their own automotive club. But as newbies they face a huge challenge; a lack of experience and an understanding of what it really means to be a classic car owner. In the all-new MotorTrend original series KEVIN HART’S MUSCLE CAR CREW, premiering Friday, July 2 only on the MotorTrend App, Kevin, John, Ron, Spank, Harry and Joey seek answers to the questions around being a devoted automotive fan, learn to navigate the challenges of owning classic vehicles and make us laugh along the way. KEVIN HART’S MUSCLE CAR CREW, produced by HartBeat Productions and Big Breakfast, is a lighthearted, hilarious journey into the car collecting world. From finding a trusted, skilled mechanic in Lucky Costa from MotorTrend’s HOT ROD GARAGE to customizing, racing, and flipping cars at auctions, Kevin and his friends settle internal debates with the help of automotive experts while gaining hard-earned knowledge in fulfilling their newfound passion. -

Discussion Guide*

Discussion Guide* A partnership between the National Association for Media Literacy Education and truTV U.S. Media Literacy Week 2018 *Suggested for use in high school and higher ed classrooms Adam Ruins Everything Discussion Guide A partnership between the National Association for Media Literacy Education and truTV INTRODUCTION During the 2018 U.S. Media Literacy Week, the National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE) and truTV are teaming up to bring episodes of the popular television show, Adam Ruins Everything to educators for use in the classroom. The partnership is designed to provide educators with unique content that will inspire relevant and rich discussion to their classrooms. This discussion guide can be used as a companion to the episodes to teach media literacy skills through inquiry based learning. Using these resources, students will gain knowledge about the origin of common information we accept as fact, their role in accepting knowledge without inquiry, and develop tools to think critically about the media messages around them. BACKGROUND Media are defined as the means of communication that reach or influence people widely (for example; radio, television, newspapers, magazines, and the Internet). Media literacy is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication and represents a necessary, inevitable, and realistic response to the complex, ever-changing electronic environment. To become a successful student, responsible citizen, productive worker, and conscientious consumer, students need to develop expertise with the increasingly sophisticated information and entertainment media that affect the way they think, feel, and behave. Media literacy is an essential life skill in the 21st Century. -

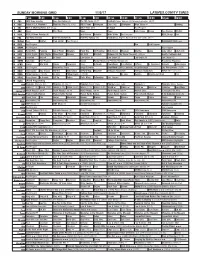

Sunday Morning Grid 11/5/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/5/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Denver Broncos at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Champion Give (TVG) Champion Nitro Circus Å Skating 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Bulletproof Monk ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Motown 25 (My Music Presents) (TVG) Å Huell’s California Adv 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 16, 2021 KEVIN HART & THE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 16, 2021 Download Photo: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1U-qHSgr2EzhI3m86TK6FjOaZDon8FlOv/view?usp=sharing Photo Credit: MotorTrend KEVIN HART & THE PLASTIC CUP BOYZ SET TO STAR IN KEVIN HART’S MUSCLE CAR CREW, THE NEW ORIGINAL AUTOMOTIVE SERIES COMING TO MOTORTREND’S STREAMING SERVICE --Eight-Episode Series Scheduled to Start Streaming in 3Q21 on the MotorTrend App-- (Los Angeles) – MotorTrend Group announced today the greenlight of KEVIN HART’S MUSCLE CAR CREW, the all-new original automotive series from actor, comedian, producer and avid car collector Kevin Hart and his famous comedy crew The Plastic Cup Boyz. KEVIN HART’S MUSCLE CAR CREW will take a lighthearted, hilarious look at the world of car collecting and what it means to be a muscle car devotee as they attempt to successfully launch their own automotive club. Production is currently underway with the series, produced by Propagate Content’s Big Breakfast and HartBeat Productions, scheduled to premiere in 3Q21 only on the MotorTrend App, the leading subscription streaming service dedicated entirely to the motoring world. Members of Kevin Hart’s crew, affectionately named The Plastic Cup Boyz, include John Clausell, Ron Everline, Spank Horton, Harry Ratchford and Joey Wells. Lucky Costa from MotorTrend’s HOT ROD GARAGE will be the house mechanic for the crew in the new series, advising them on their muscle car builds and helping them through a crash course on car culture. “Fans will have a ball experiencing this classic car journey through the eyes of Kevin Hart and The Plastic Cup Boyz,” said Alex Wellen, president and general manager, MotorTrend Group. -

Trutv Taps And/Or for Multiplatform Rebrand

TruTV Taps And/Or for Multiplatform Rebrand 07.25.2017 As Turner's truTV finalizes its brand evolution from a reality-focused network to one that's all in on comedy, it turned to Brooklyn-based creative agency And/Or for a multi-platform rebrand. "And/Or had a true understanding of our voice and a great, collaborative voice to boot," said Puja Vohra, executive vice president of marketing and digital for truTV in a statement. "We couldn't have asked for better partners on our redesign." Simplicity was the central concept that guided And/Or through the rebrand, giving truTV's marketing team a great deal of flexibility. "Part of our task was to simplify the brand so that the network talent and programming took the lead," said Kelli Miller, executive creative director at And/Or, in a statement. "This required an extremely flexible system that allowed seasonal key art to shine while maintaining a coherent underpinning that kept everything connected under the truTV brand." And/Or left the truTV logo and tagline, "Funny because it's tru," unchanged. That became the cornerstone of the brand DNA, said Miller. Staying true (tru?) to the notion that the brand needed to be simplified, And/Or stripped it down to one color and two typefaces. All of the brand elements were created to be adaptable to the network's individual shows, including Impractical Jokers, Adam Ruins Everything, The Chris Gethard Show and more. The new identity also had to support comedy's core elements such as timing, anticipation and punchline. "These ideas informed everything from animation behavior to the naming conventions of the brand elements," said Miller. -

Health Sciences Professor Shares Expertise on Trutv Tuesday Night

Health Sciences professor shares expertise on TruTV Tuesday night Monday, Aug 29, 2016 Health Sciences professor shares expertise on TruTV A Dr. Tamara Hew-Butler screenshot from her appearance on the TruTV show Adam Ruins Everything airing Tuesday, August 30 at 10 p.m. Tamara Hew-Butler, D.P.M., Ph.D., associate professor of Exercise Science in the School of Health Sciences at Oakland University, will take the national stage on Tuesday night at 10 p.m. when she appears in the new episode of Adam Ruins Everything on TruTV. The show, now in its second season, is hosted by investigative comedian Adam Conover. Each week, he reveals the hidden truths behind everything you know and love. Conover, a cast member and writer at the popular comedy website CollegeHumor, brings his original online series to TV with this series. In this week’s episode, Dr. Hew-Butler helps debunk widespread misconceptions about dehydration and how much water people should drink. She is a research expert in the condition of hyponatremia, which is low blood sodium. Dr. Hew-Butler arrived at Oakland University in 2010. She has a dual clinical and research background; working as a sports medicine clinician in Houston for eight years before pursuing a research degree at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. Both doctoral degrees combine her lifelong passion for sports - particularly long distance running - and athletic care. Her clinical passion is biomechanics, namely keeping athletes “on their feet” by focusing on injury prevention as an integral part of an athlete’s treatment plan. -

DGA Reality Directors Contact Guide

DGA’s REALITY DIRECTORS Contact Guide EF OP CH PRO T JE CT R FACT RU SE FEAR OR N W LO D BI A T E G Y S K K B E A K TAN A R N R ME O G HA R T G G S I H I N C I A E B ’ R T S A F E N D H E C X E R T C E F T T A F O S R O A P G E M M C N O I A Z F D A E R L M O I A R R E R T S S A I E A B W S D R T M A P A O T J K N A E K I E E N Y E V I B N N A C L A I R M E E A S T K M A U M L I E L T E L R C U H C A I L L A C E E N G A R N G G A R R I D T S ’ L U R A U P 7/2018 WHAT PRODUCERS AND AGENTS ARE SAYING ABOUT DGA REALITY AGREEMENTS: “The DGA has done an amazing job of building strong relationships with unscripted Producers. They understand that each show is different and work with us to structure deals that make sense for both the Producers and their Members on projects of all sizes and budgets.