California State University, Northridge Colonel John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks, However, Went Unnoticed

• D -1:>K 1.2!;EQUOJA-KING$ Ci\NYON NATIONAL PARKS History of the Parks "''' Evaluation of Historic Resources Detennination of Effect, DCP Prepared by • A. Berle Clemensen DENVER SERVICE CENTER HISTORIC PRESERVATION TEA.'! NATIONAL PAP.K SERVICE UNITED STATES DEPAR'J'}fENT OF THE l~TERIOR DENVER, COLOR..\DO SEPTEffilER 1975 i i• Pl.EA5!: RETUl1" TO: B&WScans TEallillCAL INFORMAl!tll CfNIEil 0 ·l'i «coo,;- OOIVER Sf:RV!Gf Cf!fT£R llAT!ONAL PARK S.:.'Ma j , • BRIEF HISTORY OF SEQUOIA Spanish and Mexican Period The first white men, the Spanish, entered the San Joaquin Valley in 1772. They, however, only observed the Sierra Nevada mountains. None entered the high terrain where the giant Sequoia exist. Only one explorer came close to the Sierra Nevadas. In 1806 Ensign Gabriel Moraga, venturing into the foothills, crossed and named the Rio de la Santos Reyes (River of the Holy Kings) or Kings River. Americans in the San Joaquin Valley The first band of Americans entered the Valley in 1827 when Jedediah Smith and a group of fur traders traversed it from south to north. This journey ushered in the first American frontier as fifteen years of fur trapping followed. Still, none of these men reported sighting the giant trees. It was not until 1833 that members of the Joseph R. 1lalker expedition crossed the Sierra Nevadas and received credit as the first whites to See the Sequoia trees. These trees are presumed to form part of either the present M"rced or Tuolwnregroves. Others did not learn of their find since Walker's group failed to report their discovery. -

Page 78 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 45A–1 Kaweah River and The

§ 45a–1 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 78 Kaweah River and the headwaters of that branch Fork Kaweah River to its junction with Cactus of Little Kern River known as Pecks Canyon; Creek; thence easterly along the first hydro- thence southerly and easterly along the crest of graphic divide south of Cactus Creek to its the hydrographic divide between Pecks Canyon intersection with the present west boundary of and Soda Creek to its intersection with a lateral Sequoia National Park, being the west line of divide at approximately the east line of section township 16 south, range 29 east; thence south- 2, township 19 south, range 31 east; thence erly along said west boundary to the southwest northeasterly along said lateral divide to its corner of said township; thence easterly along intersection with the township line near the the present boundary of Sequoia National Park, southeast corner of township 18 south, range 31 being the north line of township 17 south, range east of the Mount Diablo base and meridian; 29 east, to the northeast corner of said township; thence north approximately thirty-five degrees thence southerly along the present boundary of west to the summit of the butte next north of Sequoia National Park, being the west lines of Soda Creek (United States Geological Survey al- townships 17 and 18 south, range 30 east, to the titude eight thousand eight hundred and eighty- place of beginning; and all of those lands lying eight feet); thence northerly and northwesterly within the boundary line above described are in- along the crest of the hydrographic divide to a cluded in and made a part of the Roosevelt-Se- junction with the crest of the main hydro- quoia National Park; and all of those lands ex- graphic divide between the headwaters of the cluded from the present Sequoia National Park South Fork of the Kaweah River and the head- are included in and made a part of the Sequoia waters of Little Kern River; thence northerly National Forest, subject to all laws and regula- along said divide now between Horse and Cow tions applicable to the national forests. -

Tulare County Measure R Riparian-Wildlife Corridor Report

Tulare County Measure R Riparian-Wildlife Corridor Report Prepared by Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners for Tulare County Association of Govenments 11 February 2008 Executive Summary As part of an agreement with the Tulare County Association of Governments, Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners (TBWP) visited nine potential riparian and wildlife corridors in Tulare County during summer 2007. We developed a numerical ranking system and determined the five corridors with highest potential for conservation, recreation and conjunctive uses. The selected corridors include: Deer Creek Riparian Corridor, Kings River Riparian Corridor, Oaks to Tules Riparian Corridor, Lewis Creek Riparian Corridor, and Cottonwood Creek Wildlife Corridor. For each corridor, we provide a brief description and a summary of attributes and opportunities. Opportunities include flood control, groundwater recharge, recreation, tourism, and wildlife. We also provide a brief description of opportunities for an additional eight corridors that were not addressed in depth in this document. In addition, we list the Measure R transportation improvements and briefly discuss the potential wildlife impacts for each of the projects. The document concludes with an examination of other regional planning efforts that include Tulare County, including the San Joaquin Valley Blueprint, the Tulare County Bike Path Plan, the TBWP’s Sand Ridge-Tulare Lake Plan, the Kaweah Delta Water Conservation District Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP), and the USFWS Upland Species Recovery Plan. Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners, 2/11/2008 Page 2 of 30 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Goals and Objectives………………………...……………………………………………. 4 Tulare County Corridors……………………..……………………………………………. 5 Rankings………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Corridors selected for Detailed Study…………………………………………….. 5 Deer Creek Corridor………………………………………………………. 5 Kings River Corridor……………………………………………………… 8 Oaks to Tules Corridor…………………………………..………………… 10 Lewis Creek East of Lindsay……………………………………………… 12 Cottonwood Creek………………………………………...………………. -

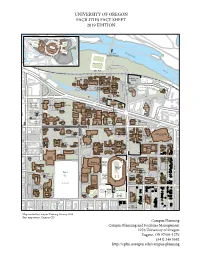

Fact Sheet Campusmap 2019

UNIVERSITY OF OREGON FACILITIES FACT SHEET 2019 MARTIN LUTHE R KING JR BLVD Hatfield-Dowlin Complex Football Practice Fields PK Park Casanova Autzen Athletic Brooks Field LEO HARRIS PKW Y Moshofsky Sports Randy and Susie Stadium Pape Complex W To Autzen illa Stadium Complex me tte Riverfront Fields R Bike Path iv er FRANKLIN BLVD Millrace Dr Campus Planning and Garage Facilities Management CPFM ZIRC MILLRACE DR Central Admin Fine Arts Power Wilkinson Studios Millrace Station Millrace House Studios 1600 Innovation Woodshop Millrace Center Urban RIVERFRONT PKWY EAST 11TH AVE Farm KC Millrace Annex Robinson Villard Northwest McKenzie Theatre Lawrence Knight Campus Christian MILLER THEATRE COMPLEX 1715 University Hope Cascade Franklin Theatre Annex Deady Onyx Bridge Lewis EAST 12TH AVE Pacific Streisinger Integrative PeaceHealth UO Allan Price Science University District Annex Computing Allen Cascade Science Klamath Commons MRI Lillis LOKEY SCIENCE COMPLEX MOSS ST LILLIS BUSINESS COMPLEX Willamette Huestis Jaqua Lokey Oregon Academic Duck Chiles Fenton Friendly Store Peterson Anstett Columbia Laboratories Center FRANKLIN BLVD VILLARD ST EAST 13TH AVE Restricted Vehicle Access Deschutes EAST 13TH AVE Volcanology Condon Chapman University Ford Carson Watson Burgess Johnson Health, Boynton Alumni Collier ST BEECH Counseling, Collier Center Tykeson House and Testing Hamilton Matthew Knight Erb Memorial Cloran Unthank Arena JOHNSON LANE 13th Ave Union (EMU) Garage Prince Robbins COLUMBIAST Schnitzer McClain EAST 14TH AVE Lucien Museum Hawthorne -

Frontispiece the 1864 Field Party of the California Geological Survey

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC ROAD GUIDE TO KINGS CANYON AND SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARKS, CENTRAL SIERRA NEVADA, CALIFORNIA By James G. Moore, Warren J. Nokleberg, and Thomas W. Sisson* Open-File Report 94-650 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. * Menlo Park, CA 94025 Frontispiece The 1864 field party of the California Geological Survey. From left to right: James T. Gardiner, Richard D. Cotter, William H. Brewer, and Clarence King. INTRODUCTION This field trip guide includes road logs for the three principal roadways on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada that are adjacent to, or pass through, parts of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (Figs. 1,2, 3). The roads include State Route 180 from Fresno to Cedar Grove in Kings Canyon Park (the Kings Canyon Highway), State Route 198 from Visalia to Sequoia Park ending near Grant Grove (the Generals Highway) and the Mineral King road (county route 375) from State Route 198 near Three Rivers to Mineral King. These roads provide a good overview of this part of the Sierra Nevada which lies in the middle of a 250 km span over which no roads completely cross the range. The Kings Canyon highway penetrates about three-quarters of the distance across the range and the State Route 198~Mineral King road traverses about one-half the distance (Figs. -

Monday, May 22, 2017 Dailyemerald.Com

MONDAY, MAY 22, 2017 DAILYEMERALD.COM ⚙ MONDAY 2017 SHASTA WEEKEND 2016 TRUMP MAY AXE STUDENT DEBT FORGIVENESS PROGRAM WRAPPING UP LAST WEEK’S NEWS THE WESTERN WORLD’S TEACHING IS RACIST OmniShuttle 24/7 Eugene Airport Shuttle www.omnishuttle.com 541-461-7959 1-800-741-5097 CALLING ALL EXTROVERTS! EmeraldEmerald Media Media Group Group is is hiring hiring students students to to join join ourour Street Street TeamTeam. Team winter Getfall paidterm. term. to Get have Get paid paidfun to handing tohave have fun funouthanding handingpapers out to out papers fellow papers tostudents. fellowto fellow students. students. Apply in person at Suite 300 ApplyApply in in person person at at our our office office in in the the EMU EMU, Basement Suite 302 or email [email protected] oror email email [email protected] [email protected] June 1st 2017 EmeraldFest.com PAGE 2 | EMERALD | MONDAY, MAY 22, 2017 NEWS NEWS WRAP UP • UO shut down its websites for maintenance; more downtime set for the future. Monday • The Atlantic published UO professor Alex Tizon’s posthumous story on his family’s slave. The story was received with some controversy and sent a shock through the Twitter-sphere. Tizon, a Pulitzer Prize win- ner, died in March at age 57. Tuesday Betsey DeVos, the Secratary of Education, might cut a student debt forgiveness program in announcement set for next week. (Creative Commons) Student debt forgiveness program may get axedaxed by Trump administration • Director of Fraternity and Sorority Life Justin Shukas announced his resignation. ➡ • The School of Journalism and Communica- WILL CAMPBELL, @WTCAMPBELL tion announced its budget plan. -

Chapter 21: Literature: John Muir

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 21 Literature: John Muir John Muir's exceptional mental and physical stamina enabled him to rigorously pursue, often in solitary fashion, the exploration of California's mountains. In the Fall of 1874 and the Spring of 1875 he climbed Mt. Shasta three times. Among the entries listed in this section are Muir's pocket notebooks kept during these climbs. His 1875 notebook contains many detailed drawings of the Shasta region. In one case, on April 28, 1875, he drew from the summit of Mt. Shasta a picture depicting an approaching storm, a storm similar to the one which would two days later, on another climb of the mountain, trap him and his climbing partner Jerome Fay on the summit of Mt. Shasta. Also listed in this section are the reports of A. F. Rodgers, who had hired Muir and Fay in the Spring of 1875 to go and take summit barometric readings. Rodgers wrote a fascinating report which vividly details the appearance and condition of Muir and Fay immediately following the overnight ordeal on April 30, 1875. Muir himself wrote stories of the ordeal that were published in several sources, including Harper's Magazine in 1877 and Picturesque California in 1888. Many of Muir's other published works describe Mt. Shasta. His earliest Mt. Shasta writings were a series of five articles printed in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin in 1874 and 1875; these have been edited and published by Robert Engberg as part of John Muir: Summering in the Sierra (not the same book as Muir's own book My First Summer in the Sierra). -

Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks

COMPLIMENTARY $2.95 2017/2018 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS SEQUOIA & KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARKS ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS This summer, Yamaha launches a new Star motorcycle designed to help you journey further…than you ever thought possible. To see the road ahead, visit YamahaMotorsports.com/Journey-Further Some motorcycles shown with custom parts, accessories, paint and bodywork. Dress properly for your ride with a helmet, eye protection, long sleeves, long pants, gloves and boots. Yamaha and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation encourage you to ride safely and respect the environment. For further information regarding the MSF course, please call 1-800-446-9227. Do not drink and ride. It is illegal and dangerous. ©2017 Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. All rights reserved. BLEED AREA PARK REGULATIONS AND SAFETY TRIM SIZE WELCOME LIVE AREA Welcome to Sequoia and Kings Canyon you’ll find myriad fun activities in the parks! National Parks. The National Park Service (NPS), Dela- Zion National Park Located in central California, the parks ware North at Sequoia and Kings Canyon is the result of erosion, extend from the San Joaquin Valley foothills National Parks and Sequoia Parks Conser- to the eastern crest of the Sierra Nevada. vancy work together to ensure that your sedimentary uplift, and If trees could be kings, their royal realms visit is memorable. Stephanie Shinmachi. would be in these two adjoining parks. This American Park Network guide to 8 ⅞ Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks is testify to nature’s size, beauty and diversity: provided to help plan your visit. -

Wilderness Fires Continue to Burn in SEKI (Pdf 54

National Park Service Sequoia and Kings Canyon 47050 Generals Hwy. U.S. Department of the Interior National Parks Three Rivers, CA 93271 559 565-3341 phone 559 565-3730 fax Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks News Release For Immediate Release Reference Number: 8550-2029 Contact: Perri Spreiser, Fire Information Officer Phone Number: (662) 231-6457 E-mail: [email protected] Wilderness Fires Continue to Burn in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks SEQUOIA AND KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARKS, Calif. September 19, 2020 – Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks continue to have two active fires burning in designated wilderness with no threats to people or property. The Rattlesnake and Moraine Fires were both caused by lighting and continue to show slow and minor fire growth. The Rattlesnake Fire is 2,078 acres and the Moraine Fire is 575 acres. Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks are in a highly fire-adapted ecosystem. This means that fire has shaped this landscape for thousands of years and the plants and animals have evolved to live with fire. The main example within the parks are the sequoia trees themselves. Not only does the giant sequoia have thick bark to provide protection from high heat sources, the cones have also developed to open only during periods of high temperatures to release seeds, generating new trees. This type of cone is referred to as serotinous. Sequoia trees would not exist today if there was not fire to support them. In addition to Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks full park closures, park managers have implemented a designated wilderness closure in response to the Rattlesnake Fire. -

Mapping Students' Perception of the University of Oregon

MAPPING STUDENTS’ PERCEPTION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF OREGON CAMPUS by BYOUNG-WOOK JUN AN EXIT PROJECT Presented to the Department of Planning, Public Policy Management and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Community and Regional Planning June 2003 ii “Mapping Students’ Perception of the University of Oregon Campus,” an exit project prepared by Byoung-Wook Jun in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s degree in the Planning, Public Policy Management. This project has been approved and accepted by: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Marc Schlossberg, Chair of the Examining Committee ________________________________________ Date Committee in charge: Dr. Marc Schlossberg, Chair Dr. Rich Margerum iii An Abstract of the Exit Project of Byoung-Wook Jun for the degree of Master of CRP in the Planning, Public Policy Management to be taken June 2003 Title: MAPPING STUDENTS’ PERCEPTION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF OREGON CAMPUS Approved: _______________________________________________ Dr. Marc Schlossberg Human and places are tied by certain meanings. The meanings can be positive, negative, or neutral, depending on how the individual, group or community evaluates the places. These meanings are premised on human’s perception of their environment. This study was intended to draw evaluative maps based on the students’ perception of the University of Oregon, and to examine the characteristics of evaluative perception through the maps. For this study, an interview survey to 225 students was conducted, and ArcMap was used to create evaluative maps and analyze the survey data. From the data and evaluative maps, this study identified that there are many elements affecting people’s image perception, and some elements create positive effects while others have negative effects on people’s perception. -

Challenge of the Big Trees

Challenge of the Big Trees Challenge of the Big Trees CHALLENGE OF THE BIG TREES Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed ©1990, Sequoia Natural History Association, Inc. CONTENTS NEXT >>> Challenge of the Big Trees ©1990, Sequoia Natural History Association dilsaver-tweed/index.htm — 12-Jul-2004 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/dilsaver-tweed/index.htm[7/2/2012 5:14:17 PM] Challenge of the Big Trees (Table of Contents) Challenge of the Big Trees Table of Contents COVER LIST OF MAPS LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS FOREWORD PREFACE CHAPTER ONE: The Natural World of the Southern Sierra CHAPTER TWO: The Native Americans and the Land CHAPTER THREE: Exploration and Exploitation (1850-1885) CHAPTER FOUR: Parks and Forests: Protection Begins (1885-1916) CHAPTER FIVE: Selling Sequoia: The Early Park Service Years (1916-1931) CHAPTER SIX: Colonel John White and Preservation in Sequoia National Park (1931- 1947) CHAPTER SEVEN: Two Battles For Kings Canyon (1931-1947) CHAPTER EIGHT: Controlling Development: How Much is Too Much? (1947-1972) CHAPTER NINE: New Directions and A Second Century (1972-1990) APPENDIX A: Visitation Statistics, 1891-1988 APPENDIX B: Superintendents of Sequoia, General Grant, and Kings Canyon National Parks NOTES TO CHAPTERS PUBLISHED SOURCES ARCHIVAL RESOURCES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INDEX (omitted from online edition) ABOUT THE AUTHORS http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/dilsaver-tweed/contents.htm[7/2/2012 5:14:22 PM] Challenge of the Big Trees (Table of Contents) List of Maps 1. Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks and Vicinity 2. Important Place Names of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks 3. -

Eugene Bicycle Map 2014

1 2 3 4 LN HILEMAN 5 6 7 W BEACON DR E BEACON DR RIVER RD PRAIRIE RD PRAIRIE COBURG SEDONA DR SYMPHONY DR FUTURA BRIARS ST BRIARS HERMAN ST HERMAN SCENIC DR SCENIC ST CHAMPAGNE BROWN ST WILLOW SPRINGDR CALUMET WAY CALUMET GREEN HILL RD HILL GREEN LN AWBREY LN DR BEACON 2 5/16 Inches = 1 Mile RIVER LOOP 1 LOOP RIVER SCOTTDALE ST SCOTTDALE 0 1 2 3 AWBREY LN ST THUNDERBIRD LINK RD LINK REDROCK WAY Mile Mile Miles Miles LARKSMEAD LN WENDOVER HYACINTH ST HYACINTH RYAN ST RYAN CARTHAGE AVE PARK ALTURA ST ALTURA CORONA ST DOYLE ST SPRING MEADOW SPRING WATERSTONE BAMPTONCT WENDOVER CALUMET AVE ST NOTTINGHAM BERRY LN BERRY AWBREY HERMAN AVE NORTHRUP DR PARK WATSON DR E BEACON DR KINGSBURY AVE ST EDWARDS DR TORRINGTON AVE TORRINGTON A ST WENDOVER A SPRING CREEK DR CLAIRMONT DR SWEETWATER LN BERINGER CT SILVER OAK SABRENA BERRYWOOD H MONYA LN MONYA SHANNON ST SHANNON EDDYSTONE WARRINGTON AVE AMPS DR AWBREY DR SCENIC AVE H I R SHAMROCK LOCKHEED DR SILVERADO E PARK DR VICTORIA LN PL TRAIL KILDARE STAVE MEREDITH CT MEREDITH CHIMNEY ROCKWAKEFIELD LN BANOVER HYACINTH ST HYACINTH ST CT OROYAN AVE KILDARE EUGENE AUCTION WAY LYNNBROOK DR LYNNBROOK ST BANNER SHENSTONE DR SHENSTONE LANCASTER DR ST BURLWOOD PRAIRIE RD DR DUBLIN AVE ANDOVER PATRICIA ST PATRICIA LIMERICK DUBLIN AVE RIO VISTA NAISMITH BLVD CORTLAND LN SWAIN LN AVE ST WOODRUFF AVE BROTHERTON RIVER LOOP 2 ST RISDEN FILBERT MACKIN AVE ST ROBBIE RIVER LOOP 2 BROTHERTON BANNER ST BANNER AVE ST KENDRA ST PL MEADOWS RIVER LOOP 2 AVE JASON CIND PARK ST KIRSTEN 1 LOOP RIVER E ALLADIN HILO DR ST R LANCASTER