John Theodore Buchholz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thuja Plicata Has Many Traditional Uses, from the Manufacture of Rope to Waterproof Hats, Nappies and Other Kinds of Clothing

photograph © Daniel Mosquin Culturally modified tree. The bark of Thuja plicata has many traditional uses, from the manufacture of rope to waterproof hats, nappies and other kinds of clothing. Careful, modest, bark stripping has little effect on the health or longevity of trees. (see pages 24 to 35) photograph © Douglas Justice 24 Tree of the Year : Thuja plicata Donn ex D. Don In this year’s Tree of the Year article DOUGLAS JUSTICE writes an account of the western red-cedar or giant arborvitae (tree of life), a species of conifers that, for centuries has been central to the lives of people of the Northwest Coast of America. “In a small clearing in the forest, a young woman is in labour. Two women companions urge her to pull hard on the cedar bark rope tied to a nearby tree. The baby, born onto a newly made cedar bark mat, cries its arrival into the Northwest Coast world. Its cradle of firmly woven cedar root, with a mattress and covering of soft-shredded cedar bark, is ready. The young woman’s husband and his uncle are on the sea in a canoe carved from a single red-cedar log and are using paddles made from knot-free yellow cedar. When they reach the fishing ground that belongs to their family, the men set out a net of cedar bark twine weighted along one edge by stones lashed to it with strong, flexible cedar withes. Cedar wood floats support the net’s upper edge. Wearing a cedar bark hat, cape and skirt to protect her from the rain and INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY TREES Opposite, A grove of 80- to 100-year-old Thuja plicata in Queen Elizabeth Park, Vancouver. -

Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks, However, Went Unnoticed

• D -1:>K 1.2!;EQUOJA-KING$ Ci\NYON NATIONAL PARKS History of the Parks "''' Evaluation of Historic Resources Detennination of Effect, DCP Prepared by • A. Berle Clemensen DENVER SERVICE CENTER HISTORIC PRESERVATION TEA.'! NATIONAL PAP.K SERVICE UNITED STATES DEPAR'J'}fENT OF THE l~TERIOR DENVER, COLOR..\DO SEPTEffilER 1975 i i• Pl.EA5!: RETUl1" TO: B&WScans TEallillCAL INFORMAl!tll CfNIEil 0 ·l'i «coo,;- OOIVER Sf:RV!Gf Cf!fT£R llAT!ONAL PARK S.:.'Ma j , • BRIEF HISTORY OF SEQUOIA Spanish and Mexican Period The first white men, the Spanish, entered the San Joaquin Valley in 1772. They, however, only observed the Sierra Nevada mountains. None entered the high terrain where the giant Sequoia exist. Only one explorer came close to the Sierra Nevadas. In 1806 Ensign Gabriel Moraga, venturing into the foothills, crossed and named the Rio de la Santos Reyes (River of the Holy Kings) or Kings River. Americans in the San Joaquin Valley The first band of Americans entered the Valley in 1827 when Jedediah Smith and a group of fur traders traversed it from south to north. This journey ushered in the first American frontier as fifteen years of fur trapping followed. Still, none of these men reported sighting the giant trees. It was not until 1833 that members of the Joseph R. 1lalker expedition crossed the Sierra Nevadas and received credit as the first whites to See the Sequoia trees. These trees are presumed to form part of either the present M"rced or Tuolwnregroves. Others did not learn of their find since Walker's group failed to report their discovery. -

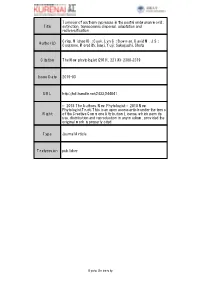

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

Callitris Forests and Woodlands

NVIS Fact sheet MVG 7 – Callitris forests and woodlands Australia’s native vegetation is a rich and fundamental Overview element of our natural heritage. It binds and nourishes our ancient soils; shelters and sustains wildlife, protects Typically, vegetation areas classified under MVG 7 – streams, wetlands, estuaries, and coastlines; and absorbs Callitris forests and woodlands: carbon dioxide while emitting oxygen. The National • comprise pure stands of Callitris that are restricted and Vegetation Information System (NVIS) has been developed generally occur in the semi-arid regions of Australia and maintained by all Australian governments to provide • in most cases Callitris species are a co-dominant a national picture that captures and explains the broad or occasional species in other vegetation groups, diversity of our native vegetation. particularly eucalypt woodlands and forests in temperate This is part of a series of fact sheets which the Australian semi-arid and sub-humid climates. After disturbance, Government developed based on NVIS Version 4.2 data to Callitris may regenerate in high densities and become provide detailed descriptions of the major vegetation groups a dominant member of a mixed canopy layer. Some of (MVGs) and other MVG types. The series is comprised of these modified communities are mapped asCallitris a fact sheet for each of the 25 MVGs to inform their use by forests or woodlands planners and policy makers. An additional eight MVGs are • are generally dominated by a herbaceous understorey available outlining other MVG types. with only a few shrubs • in New South Wales Callitris has been an important For more information on these fact sheets, including forestry timber and large monocultures have been its limitations and caveats related to its use, please see: encouraged for this purpose ‘Introduction to the Major Vegetation Group (MVG) fact sheets’. -

Cupressaceae Calocedrus Decurrens Incense Cedar

Cupressaceae Calocedrus decurrens incense cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves lustrous, decurrent, much longer than wide • laterals nearly enclosing facials • seed cone with 3 pairs of scale/bract and one central 11 NOTES AND SKETCHES 12 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis lawsoniana Port Orford cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves with glaucous bloom • tips of laterals on older stems diverging from branch (not always too obvious) • prominent white “x” pattern on underside of branchlets • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – no boss on apophysis 13 NOTES AND SKETCHES 14 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic white cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets slender, irregularly arranged (not in flattened sprays). • scale leaves blue-green with white margins, glandular on back • laterals with pointed, spreading tips, facials closely appressed • bark fibrous, ash-gray • globose seed cones 1/4, 4-5 scales, apophysis armed with central boss, blue/purple and glaucous when young, maturing in fall to red-brown 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Callitropsis nootkatensis Alaska yellow cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets very droopy • scale leaves more or less glabrous – little glaucescence • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – prominent boss on apophysis • tips of laterals tightly appressed to stem (mostly) – even on older foliage (not always the best character!) 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Taxodium distichum bald cypress Sight ID characteristics • buttressed trunks and knees • leaves -

Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part II Cupressoideae

1 2 Bull. CCP 4 (2): 51-78. (10.2015) A. Jagel & V.M. Dörken Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part II Cupressoideae Summary The cone morphology of the Cupressoideae genera Calocedrus, Thuja, Thujopsis, Chamaecyparis, Fokienia, Platycladus, Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Cupressus and Juniperus are presented in young stages, at pollination time as well as at maturity. Typical cone diagrams were drawn for each genus. In contrast to the taxodiaceous Cupressaceae, in Cupressoideae outgrowths of the seed-scale do not exist; the seed scale is completely reduced to the ovules, inserted in the axil of the cone scale. The cone scale represents the bract scale and is not a bract- /seed scale complex as is often postulated. Especially within the strongly derived groups of the Cupressoideae an increased number of ovules and the appearance of more than one row of ovules occurs. The ovules in a row develop centripetally. Each row represents one of ascending accessory shoots. Within a cone the ovules develop from proximal to distal. Within the Cupressoideae a distinct tendency can be observed shifting the fertile zone in distal parts of the cone by reducing sterile elements. In some of the most derived taxa the ovules are no longer (only) inserted axillary, but (additionally) terminal at the end of the cone axis or they alternate to the terminal cone scales (Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Juniperus). Such non-axillary ovules could be regarded as derived from axillary ones (Microbiota) or they develop directly from the apical meristem and represent elements of a terminal short-shoot (Tetraclinis, Juniperus). -

Chapter 21: Literature: John Muir

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 21 Literature: John Muir John Muir's exceptional mental and physical stamina enabled him to rigorously pursue, often in solitary fashion, the exploration of California's mountains. In the Fall of 1874 and the Spring of 1875 he climbed Mt. Shasta three times. Among the entries listed in this section are Muir's pocket notebooks kept during these climbs. His 1875 notebook contains many detailed drawings of the Shasta region. In one case, on April 28, 1875, he drew from the summit of Mt. Shasta a picture depicting an approaching storm, a storm similar to the one which would two days later, on another climb of the mountain, trap him and his climbing partner Jerome Fay on the summit of Mt. Shasta. Also listed in this section are the reports of A. F. Rodgers, who had hired Muir and Fay in the Spring of 1875 to go and take summit barometric readings. Rodgers wrote a fascinating report which vividly details the appearance and condition of Muir and Fay immediately following the overnight ordeal on April 30, 1875. Muir himself wrote stories of the ordeal that were published in several sources, including Harper's Magazine in 1877 and Picturesque California in 1888. Many of Muir's other published works describe Mt. Shasta. His earliest Mt. Shasta writings were a series of five articles printed in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin in 1874 and 1875; these have been edited and published by Robert Engberg as part of John Muir: Summering in the Sierra (not the same book as Muir's own book My First Summer in the Sierra). -

Pathways: a Story of Trails and Men (1968), by John W

Pathways: A Story of Trails and Men (1968), by John W. Bingaman • Title Page • Acknowledgements • Foreword • Preface • Contents • 1. Pioneer Trails of the West • 2. Traders, Trail Breakers, Mountain Men, & Pathmarkers of the West • 3. First Explorer of Yosemite Valley, James D. Savage • 4. First Tourist Party in Yosemite • 5. Yosemite Trails • 6. Excerpts from Reports of Army Officers & Acting Superintendents • 7. Harry Coupland Benson • 8. Gabriel Sovulewski, Dean of Trail Builders, and Frank B. Ewing • 9. Crises in Trail Maintenance • 10. My Last Patrol • Bibliography • Maps About the Author John Bingaman at Merced Grove Ranger Station, 1921 (From Sargent’s Protecting Paradise). John W. Bingaman was born June 18, 1896 in Ohio. He worked for the railroad in New York and California, then made tanks and combines during World War I. He first worked in Yosemite starting in 1918 as a packer and guide. John was appointed park ranger in 1921 and worked in several parts of Yosemite National Park. His wife Martha assisted her husband during the busy summer season. John retired in 1956. After retiring he lived in the desert in Southern California and spent summers touring various mountain areas and National Parks with their trailer. In retirement he wrote this book, Pathways, Guardians of the Yosemite: A Story of the First Rangers (1961), and The Ahwahneechees: A Story of the Yosemite Indians (1966). His autobiography is on pages 98-99 of Guardians of the Yosemite. John’s second wife was Irene. John Bingaman died April 5, 1987 in Stockton, California. Bibliographical Information John W. Bingaman (1896-1987), Pathways: A Story of Trails and Men (Lodi, California: End-kian Publishing Col, 1968), Copyright 1968 by John W. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Mao et al. 10.1073/pnas.1114319109 SI Text BEAST Analyses. In addition to a BEAST analysis that used uniform Selection of Fossil Taxa and Their Phylogenetic Positions. The in- prior distributions for all calibrations (run 1; 144-taxon dataset, tegration of fossil calibrations is the most critical step in molecular calibrations as in Table S4), we performed eight additional dating (1, 2). We only used the fossil taxa with ovulate cones that analyses to explore factors affecting estimates of divergence could be assigned unambiguously to the extant groups (Table S4). time (Fig. S3). The exact phylogenetic position of fossils used to calibrate the First, to test the effect of calibration point P, which is close to molecular clocks was determined using the total-evidence analy- the root node and is the only functional hard maximum constraint ses (following refs. 3−5). Cordaixylon iowensis was not included in in BEAST runs using uniform priors, we carried out three runs the analyses because its assignment to the crown Acrogymno- with calibrations A through O (Table S4), and calibration P set to spermae already is supported by previous cladistic analyses (also [306.2, 351.7] (run 2), [306.2, 336.5] (run 3), and [306.2, 321.4] using the total-evidence approach) (6). Two data matrices were (run 4). The age estimates obtained in runs 2, 3, and 4 largely compiled. Matrix A comprised Ginkgo biloba, 12 living repre- overlapped with those from run 1 (Fig. S3). Second, we carried out two runs with different subsets of sentatives from each conifer family, and three fossils taxa related fi to Pinaceae and Araucariaceae (16 taxa in total; Fig. -

Silviculture/Vegetation

The U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. 2 Vegetation, Including Giant Sequoias Table of Contents Vegetation, Including Giant Sequoias ............................................................................................ 3 Desired Conditions ...................................................................................................................... 4 Giant Sequoias ......................................................................................................................... 5 Mixed Conifer Forest............................................................................................................... 5 Blue Oak–Interior Live Oak (Foothill Woodlands) ................................................................ 6 Chaparral–Live Oak (Interior and Canyon Live Oaks) .......................................................... -

Challenge of the Big Trees

Challenge of the Big Trees Challenge of the Big Trees CHALLENGE OF THE BIG TREES Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed ©1990, Sequoia Natural History Association, Inc. CONTENTS NEXT >>> Challenge of the Big Trees ©1990, Sequoia Natural History Association dilsaver-tweed/index.htm — 12-Jul-2004 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/dilsaver-tweed/index.htm[7/2/2012 5:14:17 PM] Challenge of the Big Trees (Table of Contents) Challenge of the Big Trees Table of Contents COVER LIST OF MAPS LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS FOREWORD PREFACE CHAPTER ONE: The Natural World of the Southern Sierra CHAPTER TWO: The Native Americans and the Land CHAPTER THREE: Exploration and Exploitation (1850-1885) CHAPTER FOUR: Parks and Forests: Protection Begins (1885-1916) CHAPTER FIVE: Selling Sequoia: The Early Park Service Years (1916-1931) CHAPTER SIX: Colonel John White and Preservation in Sequoia National Park (1931- 1947) CHAPTER SEVEN: Two Battles For Kings Canyon (1931-1947) CHAPTER EIGHT: Controlling Development: How Much is Too Much? (1947-1972) CHAPTER NINE: New Directions and A Second Century (1972-1990) APPENDIX A: Visitation Statistics, 1891-1988 APPENDIX B: Superintendents of Sequoia, General Grant, and Kings Canyon National Parks NOTES TO CHAPTERS PUBLISHED SOURCES ARCHIVAL RESOURCES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INDEX (omitted from online edition) ABOUT THE AUTHORS http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/dilsaver-tweed/contents.htm[7/2/2012 5:14:22 PM] Challenge of the Big Trees (Table of Contents) List of Maps 1. Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks and Vicinity 2. Important Place Names of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks 3. -

Climbs and Expeditions, 1988

Climbs and Expeditions, 1988 The Editorial Board expresses its deep gratitude to the many people who have done so much to make this section possible. We cannot list them all here, but we should like to give particular thanks to the following: Kamal K. Guha, Harish Kapadia, Soli S. Mehta, H.C. Sarin, P.C. Katoch, Zafarullah Siddiqui, Josef Nyka, Tsunemichi Ikeda, Trevor Braham, Renato More, Mirella Tenderini. Cesar Morales Arnao, Vojslav Arko, Franci Savenc, Paul Nunn, Do@ Rotovnik, Jose Manuel Anglada, Jordi Pons, Josep Paytubi, Elmar Landes, Robert Renzler, Sadao Tambe, Annie Bertholet, Fridebert Widder, Silvia Metzeltin Buscaini. Luciano Ghigo, Zhou Zheng. Ying Dao Shui, Karchung Wangchuk, Lloyd Freese, Tom Elliot, Robert Seibert, and Colin Monteath. METERS TO FEET Unfortunately the American public seems still to be resisting the change from feet to meters. To assist readers from the more enlightened countries, where meters are universally used, we give the following conversion chart: meters feet meters feet meters feet meters feet 3300 10,827 4700 15,420 6100 20,013 7500 24,607 3400 11,155 4800 15,748 6200 20,342 7600 24,935 3500 11,483 4900 16,076 6300 20,670 7700 25,263 3600 11,811 5000 16,404 6400 20,998 7800 25,591 3700 12,139 5100 16,733 6500 21,326 7900 25,919 3800 12,467 5200 17.061 6600 21,654 8000 26,247 3900 12,795 5300 7,389 6700 21,982 8100 26,575 4000 13,124 5400 17,717 6800 22,3 10 8200 26,903 4100 13,452 5500 8,045 6900 22,638 8300 27,231 4200 13,780 5600 8,373 7000 22,966 8400 27,560 4300 14,108 5700 8,701 7100 23,294 8500 27,888 4400 14,436 5800 19,029 7200 23,622 8600 28,216 4500 14,764 5900 9,357 7300 23,951 8700 28,544 4600 15,092 6000 19,685 7400 24,279 8800 28,872 NOTE: All dates in this section refer to 1988 unless otherwise stated.