Scott Joplin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival

Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival By Julianna Sonnik The History Behind the Ragtime Festival Scott Joplin - pianist, composer, came to Sedalia, studied at George R. Smith College, known as the King of Ragtime -Music with a syncopated beat, dance, satirical, political, & comical lyrics Maple Leaf Club - controversial, shut down by the city in 1899 Maple Leaf Rag (1899) - 76,000 copies sold in the first 6 months of being published -Memorial concerts after his death in 1959, 1960 by Bob Darch Success from the Screen -Ragtime featured in the 1973 movie “The Sting” -Made Joplin’s “The Entertainer” and other music popular -First Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival in 1974, 1975, then took a break until 1983 -1983 Scott Joplin U.S. postage stamp -TV show possibilities -Sedalia realized they were culturally important, had way to entice their town to companies The Festival Today -38 festivals since 1974 -Up to 3,000 visitors & performers a year, from all over the world -2019: 31 states, 4 countries (Brazil, U.K., Japan, Sweden, & more) -Free & paid concerts, symposiums, Ragtime Footsteps Tour, ragtime cakewalk dance, donor party, vintage costume contest, after-hours jam sessions -Highly trained solo pianists, bands, orchestras, choirs, & more Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival -Downtown, Liberty Center, State Fairgrounds, Hotel Bothwell ballroom, & several other venues -Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation, Ragtime store, website -2020 Theme: Women of Ragtime, May 27-30 -Accessible to people with disabilities -Goals include educating locals about their town’s culture, history, growing the festival, bringing in younger visitors Impact on Sedalia & America -2019 Local Impact: $110,335 -Budget: $101,000 (grants, ticket sales, donations) -Target Market: 50+ (56% 50-64 years) -Advertising: billboards, ads, newsletter, social media -Educational Programs: Ragtime Kids, artist-in-residence program, school visits -Ragtime’s trademark syncopated beat influenced modern America’s music- hip-hop, reggae, & more. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

Scott Joplin: Maple Leaf

Maple Leaf Rag Scott Joplin Born: ? 1867 Died: April 1, 1917 Unlike many Afro-American children in the 1880s who did not get an education, According to the United States Scott attended Lincoln High School census taken in July of 1870, in Sedalia, Missouri, and later went to Scott Joplin was probably born George R. Smith College for several years. in late 1867 or early 1868. No Throughout his life, Joplin believed one is really sure where he was in the importance of education and born either. It was probably in instructed young musicians whenever northeast Texas. he could. Joplin was a self-taught Although he composed several marches, musician whose father was a some waltzes and an opera called laborer and former slave; his Treemonisha, Scott Joplin is best known mother cleaned houses. The for his “rags.” Ragtime is a style of second of six children, Scott music that has a syncopated melody in was always surrounded with which the accents are on the off beats, music. His father played the on top of a steady, march-like violin while his mother sang accompaniment. It originated in the or strummed the banjo. Scott Afro-American community and became often joined in on the violin, a dance craze that was enjoyed by the piano or by singing himself. dancers of all races. Joplin loved this He first taught himself how to music, and produced over 40 piano play the piano by practicing in “rags” during his lifetime. Ragtime the homes where his mother music helped kick off the American jazz worked; then he took lessons age, growing into Dixieland jazz, the from a professional teacher who blues, swing, bebop and eventually rock also taught him how music was ‘n roll. -

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Title Title Added Description Contributor(s) Date(s) Item # Box Publisher Additional Notes A Heritage of Spirituals Go Tell it on the Mountain for chorus of mixed John W. Work 1952 voices, three part 1121-113-001_0110 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals Go Tell it on the Mountain for chorus of women's John W. Work 1949 voices, three part 1121-113-001_0109 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals I Want Jesus to Walk with Me Edward Boatner 1949 1121-113-001_0028 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals Lord, I'm out Here on Your Word for John W. Work 1952 unaccompanied mixed chorus 1121-113-001_0111 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Lincoln Letter Ulysses Kay 1958 1121-113-001_0185 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus Like as a Father Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0188 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus O Praise the Lord Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0187 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus Sing Unto the Lord Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0186 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation Friday, November 13, 2020 Page 1 of 31 Title Added Description Contributor(s) Date(s) Item # Box Publisher Additional Notes A Wreath for Waits II. Lully, Lully Ulysses Kay 1956 1121-113-001_0189 1121-113-001 Associated Music Publishers Aeolian Choral Series King Jesus is A-Listening, negro folk song William L. -

Reframing Generated Rhythms and the Metric Matrix As Projections of Higher-Dimensional La�Ices in Sco� Joplin’S Music *

Reframing Generated Rhythms and the Metric Matrix as Projections of Higher-Dimensional Laices in Sco Joplin’s Music * Joshua W. Hahn NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.2/mto.21.27.2.hahn.php KEYWORDS: meter, rhythm, beat class theory, syncopation, ragtime, poetry, hyperspace, Joplin, Du Bois ABSTRACT: Generated rhythms and the metric matrix can both be modelled by time-domain equivalents to projections of higher-dimensional laices. Sco Joplin’s music is a case study for how these structures can illuminate both musical and philosophical aims. Musically, laice projections show how Joplin creates a sense of multiple beat streams unfolding at once. Philosophically, these structures sonically reinforce a Du Boisian approach to understanding Joplin’s work. Received August 2019 Volume 27, Number 2, June 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory Introduction [1] “Dr. Du Bois, I’ve read and reread your Souls of Black Folk,” writes Julius Monroe Troer, the protagonist of Tyehimba Jess’s 2017 Pulier Prize-winning work of poetry, Olio. “And with this small bundle of voices I hope to repay the debt and become, in some small sense, a fellow traveler along your course” (Jess 2016, 11). Jess’s Julius Monroe Troer is a fictional character inspired by James Monroe Troer (1842–1892), a Black historian who catalogued Black musical accomplishments.(1) In Jess’s narrative, Troer writes to W. E. B. Du Bois to persuade him to help publish composer Sco Joplin’s life story. -

Maple Leaf Rag

Maple Leaf Rag Scott Joplin Unlike many Afro-American children in Born: ? 1867 the 1880s who did not get an education, Died: April 1, 1917 Scott attended Lincoln High School in Sedalia, Missouri, and later went to According to the United States George R. Smith College for several census taken in July of 1870, years. Throughout his life, Joplin Scott Joplin was probably born believed in the importance of education in later 1867 or early 1868. No and instructed young musicians one is really sure where he was whenever he could. born either. It was probably in northeast Texas, although Texas Although he composed several marches, wasn’t yet a state at that time. some waltzes and an opera called Treemonisha, Scott Joplin is best known Joplin was a self-taught for his “rags.” Ragtime is a style of musician whose father was a music that has a syncopated melody in laborer and former slave; his which the accents are on the off beats, mother cleaned houses. The on top of a steady, march-like accompa- second of six children, Scott niment. It originated in the Afro- was always surrounded with American community, and became a music. His father played the dance craze that was enjoyed by dancers violin while his mother sang or of all races. Joplin loved this music, and strummed the banjo. Scott often produced over 40 piano “rags” during joined in on the violin, the his lifetime. Ragtime music helped kick piano or by singing himself. He off the American jazz age, growing into first taught himself how to play Dixieland jazz, the blues, swing, bebop the piano by practicing in the and eventually rock ‘n roll. -

MAHLERFEST XXXIV the RETURN Decadence & Debauchery | Premieres Mahler’S Fifth Symphony | 1920S: ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

August 24–28, 2021 Boulder, CO Kenneth Woods Artistic Director SAVE THE DATE MAHLERFEST XXXV May 17–22, 2022 * Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 2 in C Minor Boulder Concert Chorale Stacey Rishoi Mezzo-soprano April Fredrick Soprano Richard Wagner Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), Act One Stacey Rishoi Mezzo-soprano Brennen Guillory Tenor Matthew Sharp Bass-baritone * All programming and artists subject to change KENNETH WOODS Mahler’s First | Mahler’s Musical Heirs Symphony | Mahler and Beethoven MAHLERFEST.ORG MAHLERFEST XXXIV THE RETURN Decadence & Debauchery | Premieres Mahler’s Fifth Symphony | 1920s: ARTISTIC DIRECTOR 1 MAHLERFEST XXXIV FESTIVAL WEEK TUESDAY, AUGUST 24, 7 PM | Chamber Concert | Dairy Arts Center, 2590 Walnut Street Page 6 WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 25, 4 PM | Jason Starr Films | Boedecker Theater, Dairy Arts Center Page 9 THURSDAY, AUGUST 26, 4 PM | Chamber Concert | The Academy, 970 Aurora Avenue Page 10 FRIDAY, AUGUST 27, 8 PM | Chamber Orchestra Concert | Boulder Bandshell, 1212 Canyon Boulevard Page 13 SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 9:30 AM–3:30 PM | Symposium | License No. 1 (under the Hotel Boulderado) Page 16 SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 7 PM | Orchestral Concert Festival Finale | Macky Auditorium, CU Boulder Page 17 Pre-concert Lecture by Kenneth Woods at 6 PM ALL WEEK | Open Rehearsals, Dinners, and Other Events See full schedule online PRESIDENT’S GREETING elcome to MahlerFest XXXIV – What a year it’s been! We are back and looking to the future with great excitement and hope. I would like to thank our dedicated and gifted MahlerFest orchestra and festival musicians, our generous supporters, and our wonderful audience. I also want to acknowledge the immense contributions of Executive Director Ethan Hecht and Maestro Kenneth Woods that not only make this festival Wpossible but also facilitate its evolution. -

1. Charles Ives's Four Ragtime Dances and “True American Music”

37076_u01.qxd 3/21/08 5:35 PM Page 17 1. Charles Ives’s Four Ragtime Dances and “True American Music” Someone is quoted as saying that “ragtime is the true American music.” Anyone will admit that it is one of the many true, natural, and, nowadays, conventional means of expression. It is an idiom, perhaps a “set or series of colloquialisms,” similar to those that have added through centuries and through natural means some beauty to all languages. Ragtime has its possibilities. But it does not “represent the American nation” any more than some fine old senators represent it. Perhaps we know it now as an ore before it has been refined into a product. It may be one of nature’s ways of giving art raw material. Time will throw its vices away and weld its virtues into the fabric of our music. It has its uses, as the cruet on the boarding-house table has, but to make a meal of tomato ketchup and horse-radish, to plant a whole farm with sunflowers, even to put a sunflower into every bouquet, would be calling nature something worse than a politician. charles ives, Essays Before a Sonata Today, more than a century after its introduction, the music of ragtime is often regarded with nostalgia as a quaint, polite, antiquated music, but when it burst on the national scene in the late 1890s, its catchy melodies and en- ergetic rhythms sparked both delight and controversy. One of the many fruits of African American musical innovation, this style of popular music captivated the nation through the World War I era with its distinctive, syn- copated rhythms that enlivened solo piano music, arrangements for bands and orchestras, ballroom numbers, and countless popular songs. -

Scott Joplin American Ragtime Pianist and Composer (1867 Or 1868 - 1917)

Scott Joplin American Ragtime Pianist and Composer (1867 or 1868 - 1917) Scott Joplin was born in Texarkana, Texas around 1868, and was one of six kids. Texas is the home of long horn steer, BBQ, and everything big! Both of Scott Joplin's parents were musicians. His father played the violin at parties in North Carolina and his mother sang and played the banjo. His parents gave Scott a basic musical education, and at seven years old he began teaching himself to play the piano while his mother cleaned houses. As a boy Joplin loved to play the piano and practiced every day after school. Several local teachers helped him, but most of his musical education was guided by Julius Weiss, a German music professor who had immigrated to Texas in the late 1860’s. It wasn't too long before Joplin was performing as a pianist and singing in a quartet with three boys that lived in his hometown of Texarkana. In the late 1880's Joplin left home to become a traveling musician. He found steady work in churches and saloons. In 1893, Joplin was invited to perform at the Chicago World's Fair. The fair was attended by twenty-seven million visitors. Joplin's ragtime music was popular with the visitors and by 1897 ragtime had become a national craze. In 1895 Joplin was given his first opportunity to publish his own compositions. Four years later he published, "Maple Leaf Rag." The song quickly grew in popularity and people began referring to Joplin as the "King of Ragtime." Joplin moved to St. -

Scott Joplin's Treemonisha”--Gunter Schuller, Arr

“Scott Joplin's Treemonisha”--Gunter Schuller, arr. (1976) Added to the National Registry: 2016 Essay by Scotty Gray (guest post)* Original 1976 album cover The richness of American culture has been fascinatingly preserved by the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress by including in its 2016 listing the Deutsche Grammophon recording of the Houston Grand Opera’s 1975 performance of the African American rag time composer Scott Joplin’s opera “Treemonisha.” The opera, completed in 1910, is itself a commentary on a period of civil unrest in American history and an examination of a distinctive aspect of American culture. Joplin addressed the challenging conflicts in African American culture of the time through the story of Treemonisha, who, in the story, has been adopted by Ned and Monisha, former slaves. The old superstitions of the earlier culture are presented in the play by the “conjure men” who kidnap Treemonisha, but she is finally rescued, returned to her family, and becomes an example of a newer culture emphasizing the importance of education for women as well as men. Joplin had studied with a music teacher from Germany who exposed him to some of the literature and techniques of more classical styles and in “Treemonisha,” he clothed aspects of European opera in the distinctive garbs of ragtime. There are melodious arias, ensembles, choruses, and ballet sequences. He completed the text and music of “Treemonisha” in 1910 and it was published in a piano-vocal score in 1911. The Houston Grand Opera’s full-scale production, directed by Frank Corsaro and produced by Thomas Mowrey, was a new version orchestrated and conducted by Gunther Schuller, a classical and jazz scholar and 1994 Pulitzer Prize recipient for a distinguished musical composition by an American. -

Treemonisha: Scott Joplin's Skeptical Black Opera

Treemonisha: Scott Joplin’s Skeptical Black Opera More than a century ago, this now-famous American composer wrote an opera promoting education and the value of a skeptical perspective on superstition and supernatural claims. BRUCE A. THYER An’ it won’t be long he American composer Scott Joplin (1867–1917) is ’Fore I’ll make you from me run. deservedly famous for his many musical accomplish- I has dese bags o’ luck, ’tis true, So take care, gal, I’ll send bad luck to ments, which culminated in a posthumous Pulitzer you. Prize in 1976. An African American, Joplin is perhaps best Remus, a friend of Treemonisha’s T remonstrates: known for his many ragtime compositions such as the “Ma- pleleaf Rag,” the theme song to the popular movie The Sting. Shut up old man, enough you’ve said; You can’t fool Treemonisha—she has a Less well known are Joplin’s operas. The first, called A Guest level head. She is the only educated person of our of Honor, appeared in 1903, and his second, Treemonisha, race, was begun in 1907 and completed in 1910. For many long miles away from this place. The score of Treemonisha received less. He exits the scene and the eigh- She’ll break the spell of superstition in a positive review in the American Mu- teen-year-old Treemonisha enters and the neighborhood. sician and Art Journal in 1910 but the admonishes the conjuror: Zodzetrick leaves, and the scene only partial performance Joplin heard You have lived without working for changes to a later harvest dance. -

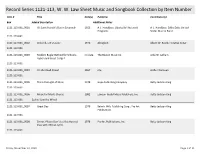

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Item Number

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Item Number Item # Title Date(s) Publisher Contributor(s) Box Added Description Additional Notes 1121-113-001_0001 It's Saint Patrick's Day in Savannah 1953 A. J. Handiboe; Liberty Bell Network A. J. Handiboe; Eddie Daly; United Programs States Marine Band 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0002 Beloved, Let Us Love 1976 Abingdon Albert W. Ream; Horatius Bonar 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0003 Modern Bugle Method for Schools, no date The Boston Music Co. Arlie W. Latham Legion and Scout Corps 1 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0004 On the Road Ahead 1967 n/a Arthur Donovan 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0005 This Little Light of Mine 1978 Hope Publishing Company Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0006 Music for Men's Chorus 1982 Lawson-Gould Music Publishers, Inc. Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 Ezekiel Saw the Wheel 1121-113-001_0007 Great Day 1976 Belwin Mills Publishing Corp.; Pro Art Betty Jackson King Publications 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0008 Sinner, Please Don't Let this Harvest 1978 Pro Art Publications, Inc. Betty Jackson King Pass with African Lyrics 1121-113-001 Friday, November 13, 2020 Page 1 of 31 Item # Title Date(s) Publisher Contributor(s) Box Added Description Additional Notes 1121-113-001_0009 Marks Choral Library 1973 Edward B. Marks Music Corporation; Belwin Betty Jackson King Mills Publishing Corp. 1121-113-001 I Want God's Heaven to be Mine 1121-113-001_0010 Stand the Storm 1980 Hope Publishing Company Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0011a God is a God! 1983 Mar-Vel Betty Jackson King; Roland M.