Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

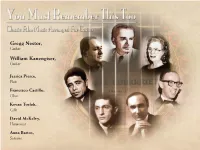

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Gary Numan - Hammersmith Apollo, London - November 28, 2014

1 Gary Numan - Hammersmith Apollo, London - November 28, 2014 by Mireille Beaulieu Original French version © Obsküre magazine - http://www.obskuremag.net http://www.obskuremag.net/articles/gary-numan-live-hammersmith-apollo-londres- 28112014/ Gary Numan’s recent concert at London’s Hammersmith Apollo had long been announced as a major event. This show was the crowning moment of the world tour Numan had undertaken in October 2013, as he was promoting his new album Splinter (Songs from a broken mind ). Undoubtedly one of the artist’s major works, Splinter garnered unparalleled public and critical acclaim. It even entered the UK Top 20 – the first Numan album to do so since Warriors in 1983. Gary Numan started this long tour in the US before visiting the UK, Ireland, Israel, continental Europe (but sadly not Paris), Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Photos: Louise Barnes and Jim Napier © Jim Napier 2 But it was also a “homecoming concert”, a return to his roots for Numan, who currently resides in Los Angeles. For the first time since 1996, he was to take over the Hammersmith Apollo, the legendary UK venue formerly known as the Hammersmith Odeon. This is where David Bowie killed off his Ziggy Stardust character in 1973... Around the same period, a teenage Gary (then still Gary Webb) would often attend gigs there. Then, with the explosion of the Numan phenomenon in 1979, the “Hammy” became for many years the London venue of his choice when he was touring. Gary, who was born in Hammersmith, obviously has a deep connection with the place. -

Martin & Co Denies Receiving Stirling Students' Complaints

Brig | October 2011 Martin & Co denies receiving Stirling sets £27,000 Stirling students’ complaints tuition fee for rest of Aya Kawanishi the UK students News Editor day, Stirling University failed students Zsuzsanna Matyak from disadvantaged backgrounds by etting agency Martin & Co de- News Editor setting its degrees cost at £27,000. We nied that any written formal are fully against tuition fees, and this complaints were received, de- he University of Stirling has decision by Stirling puts degrees there Lspite claims from Stirling stu- become one of the most ex- as expensive as the worst excesses of dents who rented a property from them pensive universities in the the English system.” between 4 August 2010 and 2 August UK after announcing its Professor Gerry McCormac, Prin- 2011. T cipal and Vice-Chancellor of Stirling decision to charge £6,750 per year, Former tenants of 23 Chandlers Court instead of the current £1,800, for stu- University, said they had no choice. Stirling, Dominique Maske and her flat- dents from England, Wales and North- “The University of Stirling has always mate, wrote to the agency on a number ern Ireland from 2012. This makes a believed that access to higher educa- of occasions regarding issues they had four-year degree cost £27,000. tion should be based on ability, not such as the lease document and the con- Hand in hand with the significantly background or the ability to pay. As dition of the flat. increased tuition fee comes a new a result of the new funding arrange- In a statement, Managing Director of range of scholarships and bursaries ments, Scottish universities have no Martin & Co Stirling, Imtiaz Ahmed, for both Scottish and rest of the UK choice but to charge fees for students said that they have “not received a for- (RUK) students, and the encourage- from the rest of the UK. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

A Historical Study of Mental Health Programming in Commercial and Public Television from 1975 to 1980

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1985 A Historical Study of Mental Health Programming in Commercial and Public Television from 1975 to 1980 Jan Jones Sarpa Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Sarpa, Jan Jones, "A Historical Study of Mental Health Programming in Commercial and Public Television from 1975 to 1980" (1985). Dissertations. 2361. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2361 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1985 Jan Jones Sarpa A HISTORICAL STUDY OF MENTAL HEALTH PROGRAMMING IN COMMERCIAL AND PUBLIC TELEVISION FROM 1975 TO 1980 by Jan Jones Sarpa A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of L~yola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education January 1985 Jan Jones Sarpa Loyola University of Chicago A HISTORICAL STUDY OF MENTAL HEALTH PROGRAMMING IN COMMERCIAL AND PUBLIC TELEVISION FROM 1975 TO 1980 There has been little to no research on the subject of mental health programming on television. This dissertation was undertaken to help alleviate this void and to discover trends and answer questions about such programming. The medium of television was researched specifically due to its access (98 percent of all U.S. -

We Have Liftoff! the Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 P.M

POPS FOUR We Have Liftoff! The Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 p.m. • MARK C. SMITH CONCERT HALL, VON BRAUN CENTER Huntsville Symphony Orchestra • C. DAVID RAGSDALE, Guest Conductor • GREGORY VAJDA, Music Director One of the nation’s major aerospace hubs, Huntsville—the “Rocket City”—has been heavily invested in the industry since Operation Paperclip brought more than 1,600 German scientists to the United States between 1945 and 1959. The Army Ballistic Missile Agency arrived at Redstone Arsenal in 1956, and Eisenhower opened NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960 with Dr. Wernher von Braun as Director. The Redstone and Saturn rockets, the “Moon Buggy” (Lunar Roving Vehicle), Skylab, the Space Shuttle Program, and the Hubble Space Telescope are just a few of the many projects led or assisted by Huntsville. Tonight’s concert celebrates our community’s vital contributions to rocketry and space exploration, at the most opportune of celestial conjunctions: July 2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon-landing mission, and 2020 brings the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, America’s leading aerospace museum and Alabama’s largest tourist attraction. S3, Inc. Pops Series Concert Sponsors: HOMECHOICE WINDOWS AND DOORS REGIONS BANK Guest Conductor Sponsor: LORETTA SPENCER 56 • HSO SEASON 65 • SPRING musical selections from 2001: A Space Odyssey Richard Strauss Fanfare from Thus Spake Zarathustra, op. 30 Johann Strauss, Jr. On the Beautiful Blue Danube, op. 314 Gustav Holst from The Planets, op. 32 Mars, the Bringer of War Venus, the Bringer of Peace Mercury, the Winged Messenger Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity INTERMISSION Mason Bates Mothership (2010, commissioned by the YouTube Symphony) John Williams Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind Alexander Courage Star Trek Through the Years Dennis McCarthy Jay Chattaway Jerry Goldsmith arr. -

Film Music Week 4 20Th Century Idioms - Jazz

Film Music Week 4 20th Century Idioms - Jazz alternative approaches to the romantic orchestra in 1950s (US & France) – with a special focus on jazz... 1950s It was not until the early 50’s that HW film scores solidly move into the 20th century (idiom). Alex North (influenced by : Bartok, Stravinsky) and Leonard Rosenman (influenced by: Schoenberg, and later, Ligeti) are important influences here. Also of note are Georges Antheil (The Plainsman, 1937) and David Raksin (Force of Evil, 1948). Prendergast suggests that in the 30’s & 40’s the films possessed somewhat operatic or unreal plots that didn’t lend themselves to dissonance or expressionistic ideas. As Hollywood moved towards more realistic portrayals, this music became more appropriate. Alex North, leader in a sparser style (as opposed to Korngold, Steiner, Newman) scored Death of a Salesman (image above)for Elia Kazan on Broadway – this led to North writing the Streetcar film score for Kazan. European influences Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). • Director Frederico Fellini &composer Nino Rota (many examples) • Director François Truffault & composerGeorges Delerue, • Composer Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the • Professionals, 1966, Composer- Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). (continued) Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

SAM :: the Society for American Music

Custom Search About Us Membershipp Why SAM? Join or Ren ew Benefits Student Forum Institutions Listserv Social M edia For Members Conferences Future Conferences New Orleans 2019 Past Conferences Perlis Concerts 2018 Conference in Kansas City Awards & Fellowshipps Cambridge Award Housewright Disse rtation Minutes from Award Volume XLIV, No. 2 Low ens Article Award the Annual (Spring 2018) Lowens Book Award Business Tucker Student Pape r Contents Award Meeting Block Fellowshipp 2018 Conference in Kansas On a beautiful Charosh Fellowshipp City Cone Fellowshipp sunny day in early Crawford Fellow shipp Graziano Fellowshipp March, members of Business Meeting Hamm Fellowshipp Minutes the Society for Hampsong Fellows hipp Awards Lowens Fellowshipp American Music From the PresidentP McCulloh Fellowsh ipp SAM Brass Band McLucas Fellowshipp gathered in Salon 3 Celebrates Thirty Shirley Fellowshipp of the Years Southern Fellowsh ipp This and all other photos of the Kansas City meeting Student Forum Thomson Fellowshipp Intercontinental taken by Michael Broyles Reportp Tick Fellowshipp Walser-McClary Hotel Kansas City Fellowshipp for our annual business meeting. President Sandra Graham called the SAM’s Culture of Giving meeting to order at 4:33 p.m. and explained some of the major changes that Johnson Publication The PaulP Whiteman Subvention have been in the works for a while. First she discussed the new SAM logo and Sight & S ound Subvention Collection at Williams recognized the work of Board Members-at-Large Steve Swayne and Glenda Digital Lectures College Student Travel Goodman, who led a committee to find a graphic designer and then to provide feedback and guidance to the designer. -

Cognition, Constraints and Conceptual Blends in Modernist Music the Pleasure of Modernism: Intention, Meaning, and the Compositional Avant-Garde, Ed

“Tone-color, movement, changing harmonic planes”: Cognition, Constraints and Conceptual Blends in Modernist Music The Pleasure of Modernism: Intention, Meaning, and the Compositional Avant-Garde, ed. Arved Ashby (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2004), 121–152. Amy Bauer I. Ligeti and the “Listenability” of Modernist Music György Ligeti has discussed his "micropolyphonic" music of the mid-1960s at some length, in an attempt to explain why its composed structure seems to bear no relation to its actual sound. Although works such as Lontano are based on strict canons, their compositional method assumes a listener will 'mishear' its structure: [In the large orchestral work Lontano] I composed . an extensively branching and yet strictly refined polyphony which, however, veers suddenly into something else. I don’t have a name for it and I don’t want to create a term for it. A kind of complex of tone-color, movement, changing harmonic planes. The polyphonic structure does not actually come through, you cannot hear it; it remains hidden in a microscopic underwater world, to us inaudible. I have retained melodic lines in the process of composition, they are governed by rules as strict as Palestrina's or those of the Flemish school, but the rules of polyphony are worked out by me. the polyphony is dissolved, like the harmony and the tone-color – to such an extent that it does not manifest itself, and yet it is there, just beneath the threshold.1 In the above passages, Ligeti appears to ally himself with modernists such as Boulez and Babbit, composers who use twelve-tone and other methods to systematically organize pitch structure. -

GLBT Historical Society Archives

GLBT Historical Society Archives - Periodicals List- Updated 01/2019 Title Alternate Title Subtitle Organization Holdings 1/10/2009 1*10 #1 (1991) - #13 (1993); Dec 1, Dec 29 (1993) 55407 Vol. 1, Series #2 (1995) incl. letter from publisher @ditup #6-8 (n.d.) vol. 1 issue 1 (Win 1992) - issue 8 (June 1994 [2 issues, diff covers]) - vol. 3 issue 15 10 Percent (July/Aug 1995) #2 (Feb 1965) - #4 (Jun 1965); #7 (Dec 1965); #3 (Winter 1966) - #4 (Summer); #10 (June 1966); #5 (Summer 1967) - #6 (Fall 1967); #13 (July 1967); Spring, 1968 some issues incl. 101 Boys Art Quarterly Guild Book Service and 101 Book Sales bulletins A Literary Magazine Publishing Women Whoever We Choose 13th Moon Thirteenth Moon To Be Vol. 3 #2 (1977) 17 P.H. fetish 'zine about male legs and feet #1 (Summer 1998) 2 Cents #4 2% Homogenized The Journal of Sex, Politics, and Dairy Products One issue (n.d.) 24-7: Notes From the Inside Commemorating Stonewall 1969-1994 issue #5 (1994) 3 in a Bed A Night in the Life 1 3 Keller Three Keller Le mensuel de Centre gai&lesbien #35 (Feb 1998), #37 (Apr 1998), #38 (May 1998), #48 (May 1999), #49 (Jun 1999) 3,000 Eyes Are Watching Me #1 (1992) 50/50 #1-#4 (June-1995-June 1996) 6010 Magazine Gay Association of Southern Africa (GASA) #2 (Jul 1987) - #3 (Aug 1987) 88 Chins #1 (Oct 1992) - #2 (Nov 1992) A Different Beat An Idea Whose Time Has Come... #1 (June 3, 1976) - #14 (Aug 1977) A Gay Dragonoid Sex Manual and Sketchbook|Gay Dragonoind Sex A Gallery of Bisexual and Hermaphrodite Love Starring the A Dragonoid Sex Manual Manual|Aqwatru' & Kaninor Dragonoid Aliens of the Polymarinus Star System vol 1 (Dec 1991); vol.