When Theories of Psychology and Composition Intersect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concert Programdownload Pdf(349

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Stockhausen's Mantra For Two Pianos Eric Huebner and Steven Beck, pianos Sound and electronic interface design: Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Sound projection: Chris Jacobs and Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Saturday, October 14, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Mantra (1970) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) Program Note by Katherine Chi To say it as simply as possible, Mantra, as it stands, is a miniature of the way a galaxy is composed. When I was composing the work, I had no accessory feelings or thoughts; I knew only that I had to fulfill the mantra. And it demanded itself, it just started blossoming. As it was being constructed through me, I somehow felt that it must be a very true picture of the way the cosmos is constructed, I’ve never worked on a piece before in which I was so sure that every note I was putting down was right. And this was due to the integral systemization - the combination of the scalar idea with the idea of deriving everything from the One. It shines very strongly. - Karlheinz Stockhausen Mantra is a seminal piece of the twentieth century, a pivotal work both in the context of Stockhausen’s compositional development and a tour de force contribution to the canon of music for two pianos. It was written in 1970 in two stages: the formal skeleton was conceived in Osaka, Japan (May 1 – June 20, 1970) and the remaining work was completed in Kürten, Germany (July 10 – August 18, 1970). -

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

Pitch-Class Set Theory: an Overture

Chapter One Pitch-Class Set Theory: An Overture A Tale of Two Continents In the late afternoon of October 24, 1999, about one hundred people were gathered in a large rehearsal room of the Rotterdam Conservatory. They were listening to a discussion between representatives of nine European countries about the teaching of music theory and music analysis. It was the third day of the Fourth European Music Analysis Conference.1 Most participants in the conference (which included a number of music theorists from Canada and the United States) had been looking forward to this session: meetings about the various analytical traditions and pedagogical practices in Europe were rare, and a broad survey of teaching methods was lacking. Most felt a need for information from beyond their country’s borders. This need was reinforced by the mobility of music students and the resulting hodgepodge of nationalities at renowned conservatories and music schools. Moreover, the European systems of higher education were on the threshold of a harmoni- zation operation. Earlier that year, on June 19, the governments of 29 coun- tries had ratifi ed the “Bologna Declaration,” a document that envisaged a unifi ed European area for higher education. Its enforcement added to the urgency of the meeting in Rotterdam. However, this meeting would not be remembered for the unusually broad rep- resentation of nationalities or for its political timeliness. What would be remem- bered was an incident which took place shortly after the audience had been invited to join in the discussion. Somebody had raised a question about classroom analysis of twentieth-century music, a recurring topic among music theory teach- ers: whereas the music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries lent itself to general analytical methodologies, the extremely diverse repertoire of the twen- tieth century seemed only to invite ad hoc approaches; how could the analysis of 1. -

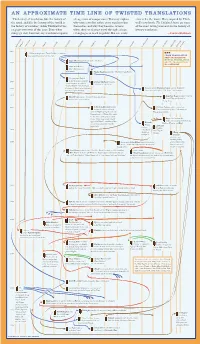

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: a Performer's Analysis

CHERNOV, KONSTANTZA, D.M.A. Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: A Performer's Analysis. (2010) Directed by Dr. James Douglass. 111 pp. The Doctoral Performance and Research submitted by Konstantza Chernov, under the direction of Dr. James Douglass at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG), in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts, consists of the following: I. Chamber Recital, Sunday, April 27, 2008, UNCG: Trio for Piano, Clarinet and Violoncello in Bb Major, op. 11 (Ludwig van Beethoven) Sonatine for Flute and Piano (Henri Dutilleux) Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major (César Franck) II. Chamber Recital, Monday, November 17, 2008, UNCG: Sonata for Violin and Piano in g minor (Claude Debussy) El Poema de una Sanluqueña, op. 28 (Joaquin Turina) Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major, op. 13 (Gabriel Fauré) III. Chamber Recital, Tuesday, April 27, 2010, UNCG: Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K. 448 (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart) The Planets, op. 32: Uranus, The Magician (Gustav Holst) The Planets, op. 32: Neptune, The Mystic (Gustav Holst) Fantasie-tableaux (Suite #1), op. 5 (Sergei Rachmaninoff) IV. Lecture-Recital, Thursday, October 28, 2010, UNCG: Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) Second Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) Third Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) V. Document: Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: A Performer's Analysis. (2010) 111 pp. This document is a performer's analysis of Leo Kraft's Fantasy for Flute and Piano (1963), Second Fantasy for Flute and Piano (1997), and Third Fantasy for Flute and Piano (2007). -

Thesis Submission

Rebuilding a Culture: Studies in Italian Music after Fascism, 1943-1953 Peter Roderick PhD Music Department of Music, University of York March 2010 Abstract The devastation enacted on the Italian nation by Mussolini’s ventennio and the Second World War had cultural as well as political effects. Combined with the fading careers of the leading generazione dell’ottanta composers (Alfredo Casella, Gian Francesco Malipiero and Ildebrando Pizzetti), it led to a historical moment of perceived crisis and artistic vulnerability within Italian contemporary music. Yet by 1953, dodecaphony had swept the artistic establishment, musical theatre was beginning a renaissance, Italian composers featured prominently at the Darmstadt Ferienkurse , Milan was a pioneering frontier for electronic composition, and contemporary music journals and concerts had become major cultural loci. What happened to effect these monumental stylistic and historical transitions? In addressing this question, this thesis provides a series of studies on music and the politics of musical culture in this ten-year period. It charts Italy’s musical journey from the cultural destruction of the post-war period to its role in the early fifties within the meteoric international rise of the avant-garde artist as institutionally and governmentally-endorsed superman. Integrating stylistic and aesthetic analysis within a historicist framework, its chapters deal with topics such as the collective memory of fascism, internationalism, anti- fascist reaction, the appropriation of serialist aesthetics, the nature of Italian modernism in the ‘aftermath’, the Italian realist/formalist debates, the contradictory politics of musical ‘commitment’, and the growth of a ‘new-music’ culture. In demonstrating how the conflict of the Second World War and its diverse aftermath precipitated a pluralistic and increasingly avant-garde musical society in Italy, this study offers new insights into the transition between pre- and post-war modernist aesthetics and brings musicological focus onto an important but little-studied era. -

Segall, Prokofiev's Symphony ..., and the Theory Of

Prokofiev’s Symphony no. 2, Yuri Kholopov, and the Theory of Twelve-Tone Chords Christopher Segall NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.18.24.2/mto.18.24.2.segall.php KEYWORDS: Sergei Prokofiev, twelve-tone technique, twelve-tone chord, aggregate chord, Russian music theory, Yuri Kholopov ABSTRACT: A small collection of works, including Prokofiev’s Symphony no. 2 (1924), include chords with all twelve pitch classes. Yuri Kholopov, the foremost late-Soviet theorist, considered twelve-tone chords a branch of twelve-tone technique. Taking Prokofiev and Kholopov as a starting point, and building on prior scholarship by Martina Homma, I assemble a history and theory of twelve-tone chords. The central theoretical problem is that of differentiation: as all twelve-tone chords contain the same twelve pitch classes, there is essentially only one twelve-tone chord. Yet twelve-tone chords can be categorized on the basis of their deployment in pitch space. Twelve-tone chords tend to exhibit three common features: they avoid doublings, they have a range of about 3 to 5.5 octaves, and their vertical interval structure follows some sort of pattern. This article contextualizes twelve-tone chords within the broader early-twentieth-century experimentation with aggregate-based composition. Received May 2017 Volume 24, Number 2, July 2018 Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory Introduction [1] This paper bases a history and theory of twelve-tone chords around an unlikely starting point: Sergei Prokofiev, whose Symphony no. 2 (1924) features a chord with all twelve pitch classes.(1) Scholars have developed sophisticated models for various aspects of twelve-tone technique—such as tone-row structure, invariance, hexachordal combinatoriality, and rotation—but with isolated exceptions have not to date examined the phenomenon of twelve-tone verticals. -

WHAT USE IS MUSIC in an OCEAN of SOUND? Towards an Object-Orientated Arts Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR WHAT USE IS MUSIC IN AN OCEAN OF SOUND? Towards an object-orientated arts practice AUSTIN SHERLAW-JOHNSON OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY Submitted for PhD DECEMBER 2016 Contents Declaration 5 Abstract 7 Preface 9 1 Running South in as Straight a Line as Possible 12 2.1 Running is Better than Walking 18 2.2 What You See Is What You Get 22 3 Filling (and Emptying) Musical Spaces 28 4.1 On the Superficial Reading of Art Objects 36 4.2 Exhibiting Boxes 40 5 Making Sounds Happen is More Important than Careful Listening 48 6.1 Little or No Input 59 6.2 What Use is Art if it is No Different from Life? 63 7 A Short Ride in a Fast Machine 72 Conclusion 79 Chronological List of Selected Works 82 Bibliography 84 Picture Credits 91 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. Name: Austin Sherlaw-Johnson Signature: Date: 23/01/18 Abstract What Use is Music in an Ocean of Sound? is a reflective statement upon a body of artistic work created over approximately five years. This work, which I will refer to as "object- orientated", was specifically carried out to find out how I might fill artistic spaces with art objects that do not rely upon expanded notions of art or music nor upon explanations as to their meaning undertaken after the fact of the moment of encounter with them. -

CLAUDIA BAEZ Paintings After Proust

ART 3 109 Ingraham Street T 646 331 3162 Brooklyn NY 11237 www.art-3gallery.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST Curated by Anne Strauss October 8 – November 22, 2014 Opening: Wednesday, October 8, 6 - 9 PM Claudia Baez, PAINTINGS after PROUST “And as she played, of all Albertine’s multiple tresses I could see but a single heart-shaped loop of black hair dinging to the side of her ear like the bow of a Velasquez Infanta.”, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.) © Claudia Baez Courtesy of ART 3 gallery Brooklyn, NY, September 19, 2014 – ART 3 opened in Bushwick in May 2014 near Luhring Augustine with its Inaugural Exhibition covered by The New York Times T Magazine, Primer. ART 3 was created by Silas Shabelewska-von Morisse, formerly of Haunch of Venison and Helly Nahmad Gallery. In July 2014, Monika Fabijanska, former Director of the Polish Cultural Institute in New York, joined ART 3 as Co-Director in charge of curatorial program, museums and institutions. ART 3 presents CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST on view at ART 3 gallery, 109 Ingraham Street, Bushwick, Brooklyn, from October 8 to November 22, 2014, Tue-Sat 12-6 PM. The opening will take place on Wednesday, October 8, from 6-9 PM. “In PAINTINGS after PROUST, Baez offers us an innovative chapter in contemporary painting in ciphering her art via a modernist work of literature within a postmodernist framework. […] In Claudia Baez’s exhibition literary narrative is poetically refracted through painting and vice versa, which the painter reminds us with artistic verve and aplomb of the adage that every picture tells a story as well as the other way around”. -

A Global Sampling of Piano Music from 1978 to 2005: a Recording Project

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A GLOBAL SAMPLING OF PIANO MUSIC FROM 1978 TO 2005 Annalee Whitehead, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2011 Dissertation directed by: Professor Bradford Gowen Piano Division, School of Music Pianists of the twenty-first century have a wealth of repertoire at their fingertips. They busily study music from the different periods Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and some of the twentieth century trying to understand the culture and performance practice of the time and the stylistic traits of each composer so they can communicate their music effectively. Unfortunately, this leaves little time to notice the composers who are writing music today. Whether this neglect proceeds from lack of time or lack of curiosity, I feel we should be connected to music that was written in our own lifetime, when we already understand the culture and have knowledge of the different styles that preceded us. Therefore, in an attempt to promote today’s composers, I have selected piano music written during my lifetime, to show that contemporary music is effective and worthwhile and deserves as much attention as the music that preceded it. This dissertation showcases piano music composed from 1978 to 2005. A point of departure in selecting the pieces for this recording project is to represent the major genres in the piano repertoire in order to show a variety of styles, moods, lengths, and difficulties. Therefore, from these recordings, there is enough variety to successfully program a complete contemporary recital from the selected works, and there is enough variety to meet the demands of pianists with different skill levels and recital programming needs.