PDF Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Announcement

Announcement Total 100 articles, created at 2016-06-09 18:04 1 Best mobile games of 2016 (pictures) Looking for a new game to play on your mobile device? Here's our pick of the best released in 2016 (so far). 2016-06-09 12:53 677Bytes (1.08/2) www.cnet.com 2 Apple revamps App Store, may not win over developers Apple Inc. announced a series of long-awaited enhancements to (1.05/2) its App Store on Wednesday, but the new features may not ease concerns of developers and analysts who say that the App Store model - and the very idea of the single-purpose app - has... 2016-06-09 08:46 4KB pctechmag.com 3 HPE Unveils Converged Systems for IoT The Edgeline EL1000 and EL4000 systems are part of a larger series of announcements by HPE to address such IoT issues as (1.02/2) security and management. 2016-06-09 12:49 5KB www.eweek.com 4 What is AmazonFresh? Amazon launches new grocery service for the UK: Can I get (1.02/2) AmazonFresh in the UK? What is AmazonFresh, Amazon launches new grocery service for the UK, Can I get AmazonFresh in the UK, where does AmazonFresh deliver, what does AmazonFresh deliver 2016-06-09 12:42 3KB www.pcadvisor.co.uk 5 Borderlands 3 UK release date, price and gamelplay rumours: Gearbox has confirmed the (1.02/2) game is being developed Gearbox, the developers behind the Borderlands series are back it again with a new game on the horizon. 2016-06-09 11:00 3KB www.pcadvisor.co.uk 6 More Than 32 Million Twitter Passwords May Have Been Hacked And Leaked On The Dark (1.02/2) Web Last week Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg's social accounts; Pinterest and Twitter were briefly hacked, with the details coming from the LinkedIn breach that happened in 2012, with the founder of the world’s biggest social network reusing the password “dadada.” This time around Twitter users have become the.. -

Mosby's Comprehensive Review of Radiography

PERPUSTAKAAN PRIBADI AN-NUR YOU’VE JUST PURCHASED MORE THAN A TEXTBOOK!* Evolve Student Resources for Callaway: Mosby’s Comprehensive Review of Radiography: The Complete Study Guide and Career Planner, Seventh Edition, include the following: • Radiography Practice Exams • Flashcards • Sample Resumes and Cover Letters Activate the complete learning experience that comes with each NEW textbook purchase by registering with your scratch-off access code at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Callaway/radiography/ If you purchased a used book and the scratch-off code at right has already been revealed, the code may have been used and cannot be re-used for registration. To purchase a new code to access these valuable study resources, simply follow the link above. Place Peel Off Sticker Here REGISTER TODAY! You can now purchase Elsevier products on Evolve! Go to evolve.elsevier.com/html/shop-promo.html to search and browse for products. * Evolve Student Resources are provided free with each NEW book purchase only. Mosby’s Comprehensive Review of Radiography The Complete Study Guide and Career Planner Seventh Edition This page intentionally left blank Mosby’s Comprehensive Review of Radiography The Complete Study Guide and Career Planner Seventh Edition William J. Callaway, MA, RT(R) Radiography Educator, Author, Speaker Springfield, Illinois 3251 Riverport Lane St. Louis, Missouri 63043 MOSBY’S COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF RADIOGRAPHY: THE COMPLETE STUDY GUIDE AND CAREER PLANNER, SEVENTH EDITION ISBN: 978-0-323-35423-3 Copyright © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All Rights Reserved. Previous editions copyrighted 2013, 2008, 2006, 2002, 2000, 1998, 1995. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

2017 Elsevier Foundation Annual Report

2017 Elsevier Foundation Report Médecins Sans Frontiers doctors conduct a Phase III rotavirus vaccine trial at Epicentre’s Niger Research Center at the Maradi Hospital, which receives an annual capacity building grant of $100,000 from the Elsevier Foundation. © KRISHAN Cheyenne/MSF White City students at a recent Imperial College London workshop with the student drone society. The Elsevier Foundation supported Maker’s Challenge space will launch in September, hosting future White City students as they navigate 3D printers, tackle robotics and many other tech challenges. © Imperial College London 2017 OWSD-Elsevier Foundation woman scientist award winner Felycia Edi Soetaredjo, PhD, Lecturer at Widya Mandala Surabaya Catholic University in Surabaya, Indonesia, was recognized for her work utilizing waste and cheap materials for environmental remediation of renewable energy. © Widya Mandala Surabaya Catholic University The Elsevier Foundation 2017 Board Report 2 Contents Foreword: Youngsuk “YS” Chi, President of the Elsevier Foundation I. The Elsevier Foundation 1. Who we are 2. Our Board 3. Our Programs 4. Our Future II. Our Programs 1. Health & Innovation 2. Research in Developing Countries 3. Diversity in STM 4. Technology for Development IV. Matching Gift V. Media Outreach VI. Financial Overview VII. Appendix The Elsevier Foundation 2017 Board Report 3 The Elsevier Foundation 2017 Board Report 4 Foreword On the occasion of the September 2017 Elsevier Foundation Board Meeting It has been an incredible privilege to steer collaboration in Sustainability. The TWAS the Elsevier Foundation’s development Elsevier Foundation Program provides over the last decade. I continue to be travel grants for PhD’s and postdoc inspired by the dedication and resolve of scientists studying in sustainability fields this group as we strive to tackle important and hosts case study competitions to global challenges. -

Elsevier Overview

| 1 Elsevier Overview Helena Paczuska, Regional Sales Manager CE, EE, Middle Asia Presented By Helena Paczuska Date 23.05.2018, Minsk | 2 | 3 IMPRINTS • Amirsys • Academic Press • Butterworth–Heinemann • Churchill Livingstone • Medicine Publishing • Mosby • Morgan Kaufmann Publishers • Saunders • William Andrew • and others… | 4 ELSEVIER PUBLISH IN CHEMISTRY • 300 OVER JOURNALS INCLUDING Journal of Colloid and Interface Science Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells Electrochimica Acta Biosensors and Bioelectronics Applied Catalysis B: Environmental • MORE THAN 78,842 ARTICLES PUBLISHED IN THE LAST YEAR • 4,897,103 CITATIONS • SCIENCE DIRECT, REAXYS, KNOVEL, SCOPUS • GREAT ELSEVIER’S WEBSITE • OVER 3,800 CHEMISTRY BOOKS | 5 BEST SELLING CHEMISTRY BOOKS Descriptive Inorganic Chemistry provides updated coverage of the synthesis, reactions, and properties of elements and inorganic compounds | 6 BEST SELLING CHEMISTRY BOOKS The Immunoassay Handbook provides an excellent, updated guide to the science, technology and applications of ELISA and other immunoassays | 7 BEST SELLING CHEMISTRY BOOKS Radioactivity: Introduction and History, From the Quantum to Quarks • PROSE 2017 award winner • provides an overview of radioactivity from natural and artificial sources on earth, radiation of cosmic origins, and an introduction to the atom and its nucleus. | 8 BEST SELLING CHEMISTRY BOOKS Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis innovative reference work includes 250 organic reactions and their strategic use in the synthesis of -

RELX Group Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015

Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015 Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015 RELX Group is a world-leading provider of information and analytics for professional and business customers across industries. We help scientists make new discoveries, lawyers win cases, doctors save lives and insurance companies offer customers lower prices. We save taxpayers and consumers money by preventing fraud and help executives forge commercial relationships with their clients. In short, we enable our customers to make better decisions, get better results and be more productive. RELX PLC is a London listed holding company which owns 52.9 percent of RELX Group. RELX NV is an Amsterdam listed holding company which owns 47.1 percent of RELX Group. Forward-looking statements The Reports and Financial Statements 2015 contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the US Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. These statements are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results or outcomes to differ materially from those currently being anticipated. The terms “estimate”, “project”, “plan”, “intend”, “expect”, “should be”, “will be”, “believe”, “trends” and similar expressions identify forward-looking statements. Factors which may cause future outcomes to differ from those foreseen in forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to competitive factors in the industries in which the Group operates; demand for the Group’s products and services; exchange rate fluctuations; general economic and business conditions; legislative, fiscal, tax and regulatory developments and political risks; the availability of third-party content and data; breaches of our data security systems and interruptions in our information technology systems; changes in law and legal interpretations affecting the Group’s intellectual property rights and other risks referenced from time to time in the filings of the Group with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. -

Alternative Textbooks Publishers

ALTERNATIVE TEXT PUBLISHERS TUTORING SERVICES 2071 CEDAR HALL ALTERNATIVE TEXT PUBLISHERS Below is a list of all the publishers we work with to provide alternative text files. Aaronco Pet Products, Inc. Iowa State: Extension and Outreach Abrams Publishing Jones & Bartlett Learning ACR Publications KendallHunt Publishing Alpine Publisher Kogan Page American Health Information Management Associations Labyrinth Learning American Hotels and Lodging Legal Books Distributing American Technical Publishers Lippincott Williams and Wilkins American Welding Society Longleaf Services AOTA Press Lynne Rienner Publishers Apress Macmillan Higher Education Associated Press Manning Publications ATI Nursing Education McGraw-Hill Education American Water Works Association Mike Holt Enterprises Baker Publishing Group Morton Publishing Company Barron's Mosby Bedford/St. Martin's Murach Books Bison Books NAEYC Blackwell Books NASW Press National Board for Certification in Bloomsbury Publishing Dental Laboratory Technology (NBC) National Restaurant Association/ Blue Book, The ServSafe Blue Door Publishing Office of Water Programs BookLand Press Openstax Broadview Press O'Reilly Media Building Performance Institute, Inc. Oxford University Press BVT Publishing Paradigm Publishing Cadquest Pearson Custom Editions ALTERNATIVE TEXT PUBLISHERS Cambridge University Press Pearson Education CE Publishing Peguin Books Cengage Learning Pennwell Books Charles C. Thomas, Publisher Picador Charles Thomas Publisher Pioneer Drama Cheng & Tsui PlanningShop Chicago Distribution -

Advanced Textiles for Wound Care

Woodhead Publishing in Textiles: Number 85 Advanced textiles for wound care Edited by S. Rajendran Oxford Cambridge New Delhi © 2009 Woodhead Publishing Limited The Textile Institute and Woodhead Publishing The Textile Institute is a unique organisation in textiles, clothing and footwear. Incorporated in England by a Royal Charter granted in 1925, the Institute has individual and corporate members in over 90 countries. The aim of the Institute is to facilitate learning, recognise achievement, reward excellence and disseminate information within the global textiles, clothing and footwear industries. Historically, The Textile Institute has published books of interest to its members and the textile industry. To maintain this policy, the Institute has entered into partnership with Woodhead Publishing Limited to ensure that Institute members and the textile industry continue to have access to high calibre titles on textile science and technology. Most Woodhead titles on textiles are now published in collaboration with The Textile Institute. Through this arrangement, the Institute provides an Editorial Board which advises Woodhead on appropriate titles for future publication and suggests possible editors and authors for these books. Each book published under this arrangement carries the Institute’s logo. Woodhead books published in collaboration with The Textile Institute are offered to Textile Institute members at a substantial discount. These books, together with those published by The Textile Institute that are still in print, are offered on the Woodhead web site at: www.woodheadpublishing.com. Textile Institute books still in print are also available directly from the Institute’s website at: www.textileinstitutebooks.com. A list of Woodhead books on textile science and technology, most of which have been published in collaboration with The Textile Institute, can be found at the end of the contents pages. -

Elsevier Offers 950 New Health Titles to Research4life

October 12, 2011 Ylann Schemm Phone: +31 20 485 2025 E-mail:[email protected] Elsevier Offers 950 New Health Titles to Research4Life Leading health sciences publisher makes key Mosby, Saunders, Churchill Livingstone electronic titles freely available through UN developing world research access program Amsterdam, NL October 12, 2011 - Elsevier, a world-leading publisher of scientific, technical and medical information products and services, today announced that it is contributing an additional 950 electronic books to Research4Life, a public-private partnership working to achieve the UN’s Millennium Development Goals by providing developing world access to critical scientific research. Building on the 800 existing Elsevier science and technology books, the new electronic books cover Clinical Medicine (438 titles), Health Professions (332 titles), Veterinary Medicine (174 titles), and Clinical Dentistry (24 titles). These include seminal works such as Clinical Gynecology , Cancer Pain , Pain Medicine , Spinal Cord Injuries , and Saunders Manual of Small Animal Practice and will be accessible to users by the end of the year. "Health practitioners and researchers in developing countries will benefit greatly from this increased ebooks offering, said Kimberly Parker, HINARI Programme Manager at the WHO, “We greatly appreciate the efforts made by Research4Life partners to continuously improve and update their content offering to those who need it most.” “Contributing clinical titles helps to support doctors and nurses in the developing world -

Synthesizing Qualitative Evidence

Synthesizing Qualitative Evidence Alan Pearson Suzi Robertson-Malt Leslie Rittenmeyer JBI-Book2 Cov.indd 1 9/8/11 7:54 PM P1: OSO/OVY P2: OSO/OVY QC: OSO/OVY T1: OSO LWBK991-Book2-FM LWBK991-Sample-v1 September 1, 2011 7:20 Synthesizing Qualitative Evidence Alan Pearson Suzi Robertson-Malt Leslie Rittenmeyer Lippincott-Joanna Briggs Institute Synthesis Science in Healthcare Series: Book 2 1 P1: OSO/OVY P2: OSO/OVY QC: OSO/OVY T1: OSO LWBK991-Book2-FM LWBK991-Sample-v1 September 1, 2011 7:20 2 Publisher: Anne Dabrow Woods, MSN, RN, CRNP, ANP-BC Editor: Professor Alan Pearson, AM, Professor of Evidence Based Healthcare and Executive Director of the Joanna Briggs Institute; Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Adelaide, SA 5005 Australia Production Director: Leslie Caruso Managing Editor, Production: Erika Fedell Production Editor: Sarah Lemore Creative Director: Larry Pezzato Copyright C 2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business. Two Commerce Square 2001 Market Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 ISBN 978-1-4511-6384-1 Printed in Australia All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above mentioned copyright. -

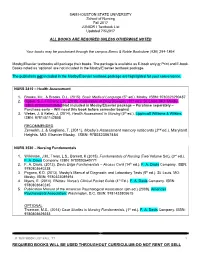

REQUIRED BOOKS WILL BE USED THROUGHOUT CURRICULUM-DO NOT RENT OR SELL JUNIOR I Textbook List Updated 3/29/2017

SAM HOUSTON STATE UNIVERSITY School of Nursing Fall 2017 JUNIOR I Textbook List Updated 7/5/2017 ALL BOOKS ARE REQUIRED UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED Your books may be purchased through the campus Barns & Noble Bookstore (936) 294-1864. Mosby/Elsevier textbooks will package their books. The package is available as E-book only or Print and E-book. Books noted as ‘optional’ are not included in the Mosby/Elsevier textbook package. The publishers not included in the Mosby/Elsevier textbook package are highlighted for your convenience. NURS 3410 – Health Assessment 1. Brooks, M.L. & Brooks, D.L. (2015). Basic Medical Language (5th ed.). Mosby. ISBN: 9780323290487 2. Ogden, S.J., Fluharty, L.K. (2015). Calculation of Drug Dosages (10th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. ISBN: 978032331069-7(Not included in Mosby/Elsevier package – Purchase separately – Purchase early – Will need this book before semester begins) 3. Weber, J. & Kelley, J. (2014). Health Assessment in Nursing (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN: 9781451142808 RECOMMENDED Zerwekh, J, & Gaglione, T. (2011). Mosby’s Assessment memory notecards (2nd ed.). Maryland Heights, MO: Elsevier Mosby. ISBN: 9780323067454 NURS 3530 – Nursing Fundamentals 1. Wilkinson, J.M., Treas, L.S., Barnett, K (2015). Fundamentals of Nursing (Two Volume Set), (3rd ed.). F. A. Davis Company. ISBN: 9780803640771 2. F. A. Davis, (2013). Davis Edge Fundamentals – Access Card (14th ed.). F. A. Davis Company. ISBN: 9780803640238 3. Pagana, K.D. (2013). Mosby’s Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. ISBN: 9780323089494 4. Myers, E. (2014). RNotes: Nurse’s Clinical Pocket Guide (4th Ed.). -

Reading List for Diagnostic Radiography Courses, 2021 Entry

Reading List for Diagnostic Radiography courses, 2021 entry BSc (Hons) Diagnostic Radiography BSc (Hons) Diagnostic Radiography with Foundation Ultrasonography BSc (Hons) Diagnostic Radiography with Integrated Foundation Year We are often are asked by students: “…which textbooks should I buy?” There are many different textbooks that are suitable for your studies and, as you progress, other texts will also become important. You are not expected to purchase every title below, and we would encourage you to try them before you buy! Copies of all these books and other electronic resources will be available to you via the School’s “Life Science Resource Centre” (LSRC) and both University and NHS medical libraries. Many students do choose to purchase Clark’s Positioning in Radiography, which is highlighted in yellow in the list below, however, it is not compulsory that you purchase this. Additionally, special purchase offers may occasionally be available from publisher stands at the Freshers’ events when you arrive. If you wish to complete any reading prior to the start date of your course, we would encourage you to look at the HCPC website to look at standards, the HSE website for radiation protection and NICE to see which guidance involves imaging: o https://www.hcpc-uk.org/ o http://www.hse.gov.uk/radiation/ionising/protection.htm o https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance?action=bytreatment&treatments=dia gnostic%20imaging General: Adler, A.M. & Carlton, R.R. (2015) Introduction to Radiologic Sciences and Patient Care, (6th ed.) London: Saunders Elsevier. Ball,J., Moore,A.D., & Turner, S. (2008) Ball and Moore's Essential Physics for Radiographers. -

Science and Medical Publishers Imprints List Version 1.1, October 2007 8 October 2007 Version

Science and Medical Publishers Imprints List Version 1.1, October 2007 8 October 2007 version Publishing house Imprints & former imprints Internet site or e-mail address for permissions contacts or information American Association AAAS http://www.sciencemag.org/help/readers/per for the Advancement of Science (magazine) missions.dtl Science American Chemical ACS http://pubs.acs.org/copyright/index.html Society Chemical Abstracts Service CAS American Institute of AIP http://journals.aip.org/copyright.html Physics [include AIP member societies?] [email protected] American Medical AMA http://pubs.ama- Association assn.org/misc/permissions.dtl American Physical APS http://librarians.aps.org/permissionscopy.htm Society l American Psychological APA http://www.apa.org/about/copyright.html Association American Society of ASCE http://www.pubs.asce.org/authors/Rightslink Civil Engineers WelcomePage.htm American Society of ASCO http://jco.ascopubs.org/misc/permissions.sht Clinical Oncology ml Association of ACM http://www.acm.org/pubs/copyright_policy/ Computing Machinery, Inc. Atlas Medical Clinical Publishing http://www.clinicalpublishing.co.uk/contact. Publishing Ltd asp BMJ Publishing Group British Medical Journal http://journals.bmj.com/misc/permissions.dtl BMJ Brill Academic Brill http://www.brill.nl/default.aspx?partid=15 Publishers Hotei Publishing IDC Martinus Nijhoff VSP Cambridge University CUP Press CABI CSIRO Publishing CSIRO http://www.publish.csiro.au/nid/182.htm#8 Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (Australia)