6 from Rainbow to Confetti: the 1960S and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Omc Special Offer Modified

The OMC Gallery - NEW website - Special offers for a limited time only Pierre Alechinsky (1927 Belgium) One of the founders of the CoBrA group, whose dedication to primitive form and often violent strokes of color paralleled the American abstract expressionist movement. The group was formed as a reaction to the formal, refined art popular in other European cities immediately after World War II. The artist's style, anguished during the CoBrA period, softened perceptibly as acceptance for his art grew, but it remains strongly expressionistic. He is particularly adept at achieving subtleties and intensities of color in the lithographic process. The recipient of the Andrew Mellon Prize in 1977, Alechinsky is represented in the collections of sixty-five of the world's leading museums, incl. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid. He has also been honored with a permanent room in the Louisiana Museumin Denmark. The winner of the first Andrew W. Mellon Prize for Painting (1977) and the French Grand Prix National for painting in 1984, Alechinsky has been recognized in recent years as one of the most significant living artists. (The art market has also noticed his stature: one of his paintings sold at auction several years ago for over $2,000,000.) Alechinsky was just barely out of his teens when he burst onto the art scene as one of the original members of the COBRA group, and over the years he has emerged as one of the most imaginative and witty artists of our times. Alechinsky fans are everywhere. -

HUMAN ANIMALS the ART of COBRA COBRA CONTEMPORARY LEGACY

HUMAN ANIMALS THe ART OF COBRA COBRA CONTEMPORARY LEGACY September 15-November 20, 2016 University Museum of Contemporary Art The Cobra Belgium, included twice as many works as the first and displayed a more mature and sophisticated side of Cobra. The show included Movement several well-known artists like Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró and Wifredo Lam, and thus demonstrated Cobra’s acceptance into the wider artistic community. Despite this, the show’s unfavorable reviews and the onset of tuberculosis in Jorn and Dotremont forced the group Cobra was formed in Paris in 1948 as an international avant-garde to split up and cease to exist as a coherent, international network. movement that united artists and poets of three cities —Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam—by Christian Dotremont (Belgian, 1922– In the 1950s, artists all around Europe searched for ways to confront 1979), Joseph Noiret (Belgian, 1927–2012), Asger Jorn (Danish, 1914– the traumatic history and legacy of the Second World War. Artists 1973), Karel Appel (Dutch, 1921–2006), Constant (Dutch, 1920–2005), focused internationally on new forms of expressive abstraction in and Corneille (Dutch, 1922–2010). The Cobra artists were inspired paint as well as other materials. Interest was revived in movements by the idea of the “human animal,” a playful or perhaps satirical like German Expressionism, formerly considered “degenerate” under representation of people’s animalistic instincts and desires, while Fascism. Historical Expressionism and Surrealism were the major evoking the symbolic relationship between humans, animals, and the inspirations for Cobra. Abstract Expressionism in the United States natural environment. The group chose the snake as a totem because was a parallel contemporary movement, but Cobra artists differed of the animal’s universal presence as a mythic and religious symbol. -

Karel Appel Art As Celebration!

Karel Appel Art as Celebration! 24 February – 20 August 2017 Press preview: 23 February 2017 11 am – 2 pm The Owlman no. 1, 1960, acrylic on olive tree trunk Opening: 23 February 6 – 9 pm Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris Photo: Karel Appel Foundation © Karel Appel Foundation/ADAGP, Paris 2017 Taking as its starting point a remarkable group of twenty-one paintings Museum Director and sculptures donated by the Karel Appel Foundation in Amsterdam, Fabrice Hergott the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris is presenting an exhibition covering the artist's entire career, from the CoBrA years to his death in Exhibition curator 2006. Choghakate Kazarian Visitor information The cosmopolitan Dutch artist Karel Appel is known as one of the founding Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de members of the CoBrA group, created in Paris in 1948 and self-dissolved in Paris 1951. With members including Asger Jorn and Pierre Alechinsky, CoBrA set 11 Avenue du Président Wilson out to eclipse such contemporary academic forms as abstract art, which they 75116 Paris Tel. 01 53 67 40 00 saw as too rigid and rational. They proposed instead a spontaneous, www.mam.paris.fr experimental art that included various practices inspired by Primitivism. They were especially drawn to children's drawings and the art of the mentally Open Tuesday – Sunday disturbed, and held fast to the international aspirations characteristic of the 10 am – 6 pm Late closing: Thursday 10 pm avant-garde. Catalogue published by Paris Contemporary with Jean Dubuffet's Art Brut et Compagnie, also founded in Musées 39,90 € 1948, CoBrA was part of the same counter-culture, rejecting established values, calling for a fresh start freed of convention, and espousing the Admission Full rate: 10 € spontaneity of naive art. -

The Influence of Chinese Calligraphy on Western Informel Painting Was Published in German in 1985

Marguerite Müller-Yao 姚 慧 The Influence of Dr.Marguerite Hui Müller-Yao 2000 Chinese Calligraphy From 1964 – 2014 a Chinese artist was resident in Germany: Dr. Marguerite Hui Müller-Yao. She learned in China traditional Chinese arts - calligraphy, ink painting, poetry – before studying Western modern art in Germany. The subject of her artistic and scientific work was an attempt of a synthesis on between the old traditions of China and the ways and forms of thought and design of modern Western culture. In her artistic work she searched on one hand to develop the traditional ink Western Informel painting and calligraphy through modern Western expression, on the other Marguerite Müller-Yao hand to deepen the formal language of modern painting, graphics and object art by referring back to the ideas of Chinese calligraphic tradition and Painting the principles of Chinese ink painting. In her academic work she was dedicated to the investigation of the relations between the Western Informel Painting and Chinese Calligraphy. This 中國書法藝術對西洋繪畫的影響 work, which deals with the influence of the art of Chinese Calligraphy on the Western Informel painting is an attempt to contribute a little to the understanding of some of the essential aspects of two cultures and their relations: the Western European-American on one hand and the East-Asian, particularly the Chinese, on the other hand. The subject of this work concerns an aspect of intercultural relations between the East and the West, especially the artistic relations between Eastern Asia and Europe/America in Düsseldorf 2015 a certain direction, from the East to the West. -

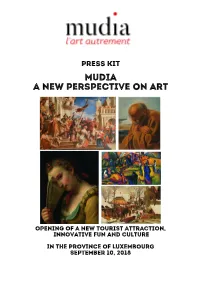

Mudia a New Perspective on Art

PRESS KIT MUDIA A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON ART OPENING OF A NEW TOURIST ATTRACTION, INNOVATIVE FUN AND CULTURE IN THE PROVINCE OF LUXEMBOURG SEPTEMBER 10, 2018 On September 10, 2018, MUDIA, a new tourist attraction, will open its doors in the Province of Luxembourg. As MUDIA houses over 300 works and takes a unique educational approach, its inauguration will prove to be one of the milestones of 2018, both on the Belgian scene and internationally. Initiated by a Belgian art lover and supported by contributions from Belgian and international private collections, MUDIA brings together numerous original masterpieces from the Renaissance to the contemporary era, by Veronese, Brueghel, Rodin, Spilliaert, Van Dongen, Wouters, Picasso, Modigliani, Giacometti, Magritte, Hergé, Franquin, Geluck and many more. Paintings, sculptures, drawings, comics, photographs, cinema and more all co- exist in a playful, digital and high-tech tour that invites the public to participate in its various stages, while learning, being entertained and understanding the universe of art and its evolution. The idea is to create a veritable spectacle based on art which is unique in Europe. MUDIA, a unique visitor experience In a space covering over 1,000 m2, with a total of twenty different galleries, MUDIA offers informed and unsuspecting visitors alike a global, playful vision of the history of art. MUDIA boasts over 300 original works, covering forty-six different art movements. Among them are many works by renowned artists, including, but not limited to: Felicien Rops Fernand Khnopff Léon Spilliaert Odilon Redon František Kupka Alphonse Mucha Gustav Klimt Auguste Rodin Émile Claus Rik Wouters Fernand Wery Kees Van Dongen Pablo Picasso Fernand Léger Amedeo Modigliani Paul Klee Oscar Jespers Gustave De Smet Alberto Giacometti René Magritte Paul Delvaux Raoul Ubac Jean Dubuffet Pierre Alechinsky Andy Warhol Marcel Broodthaers Pol Bury Hergé Franquin Philippe Geluck Katarzyna Górna Paolo Ventura .. -

A Child's Play

Klee and Cobra – a child’s play The exhibition Klee and Cobra – a child’s play was conceptualized by Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern in cooperation with LOUISIANA Museum of Modern Art, Humblebaek and Cobra Museum of Modern Art, Amstelveen. The exhibition Klee and Cobra – a child’s play is focused on the topic of the discovery of children’s creativity for artistic expression in the work of Paul Klee and the Cobra artists. The show will also highlight the importance of Paul Klee’s work and artistic thinking for Cobra in the 1940ies. The Exhibition will comprise approximately 120 works by Paul Klee and 100 works by Cobra artists as well as a great quantity of documents. The discovery of children’s potential for artistic expression provided an important impulse to the early 20th-century avant-garde, and to this day has remained a source of inspiration to artists. Both Kandinsky and Klee gained important artistic impulses from the debate, and from exploring their own childhood drawings. Almost forty years later – under different historic circumstances – immersing themselves into the imagery of children inspired the Cobra group of artists to venture into new artistic and political territory. “Ur-beginnings“ of art “In every children’s drawing without exception the object’s inner sound reveals itself,“ Kandinsky wrote in his 1912 essay, “On the Question of Form“. In that same year Paul Klee called for a return to the “ur-beginnings of art one is more likely to find in a museum of enthnography or in the nursery at home. (…) The more helpless these children, the more instructive their art.“ Thirty-six years later, Constant’s Cobra manifesto for the journal Reflex followed seamlessly on: “The child knows no other law than that of his awareness of being alive, and only wants to express that feeling.“ The exhibition Klee and Cobra – a child’s play presents the return of artists to their childhood “ur-beginnings“ as an elemental visual experience; it also places the relevance of this act in terms of art and cultural history in the historical and political context of the time. -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

Pierre Alechinsky Cobra Vivant Pierre Alechinsky Cobra Lives Jean-Loup Bourget

Document generated on 09/29/2021 7:09 p.m. Vie des arts Pierre Alechinsky Cobra vivant Pierre Alechinsky Cobra Lives Jean-Loup Bourget Volume 22, Number 90, Spring 1978 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/54844ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La Société La Vie des Arts ISSN 0042-5435 (print) 1923-3183 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Bourget, J.-L. (1978). Pierre Alechinsky : cobra vivant / Pierre Alechinsky: Cobra Lives. Vie des arts, 22(90), 58–93. Tous droits réservés © La Société La Vie des Arts, 1978 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ PIERRE ALECHINSKY cobra vivant Jean-Loup Bourget Pierre Alechinsky a reçu en 1976, pour l'ensemble de son œuvre, le Prix Andrew W. Mellon, d'un mon tant de 50 000 dollars, qui lui vaut en outre une rétrospective au Musée des Beaux-Arts du Carnegie Institute de Pittsburgh. Cette exposition se rend en suite à Toronto, à l'Art Gallery of Ontario1. D'autre part, des œuvres récentes d'Alechinsky ont été récem ment présentées à la Galerie Lefebre de New-York. Simultanément, sont publiés, par le Carnegie Institute, Pierre Alechinsky, Paintings and Writings et, par Abrams, Alechinsky, ouvrages réunissant des textes d'Ionesco, d'Alechinsky, des reproductions (dont plu sieurs lithographies originales) et une documentation très fouillée sur la vie du peintre2. -

L'aquila 1962. “Alternative Attuali” E L'idea Di “Mostra-Saggio”

Luca Pietro Nicoletti L’Aquila 1962. “Alternative Attuali” e l’idea di “mostra-saggio” Abstract Il seguente contributo analizza, su fonti d’archivio, la prima edizione della manifestazione ideata e organizzata da Enrico Crispolti presso il Forte Cinquecentesco dell’Aquila, soffermandosi sui caratteri di maggiore novità proposti da questa rassegna rispetto al panorama coevo. Con Alternative Attuali , infatti, il critico romano proponeva su larga scala un nuovo tipo di collettiva, già sperimentato in piccolo a Roma con Possibilità di relazione: non una semplice rassegna di artisti, ma la proposta di un dialogo, senza gerarchie di merito, fra posizioni diverse (le “alternative”) volte al superamento dell’Informale. Con il modello della “mostra-saggio”, arricchita da un vero e proprio dibattito affidato alle pagine del catalogo, veniva per la prima volta applicata una idea espositiva che cercasse di sistematizzare in prospettiva critica (e in proiezione storica) la situazione presente. The following paper analyses, from archive sources, the first edition of the show created and organised by Enrico Crispolti at the Forte Cinquecentesco in L’Aquila, focussing on the newest aspects of this exhibition compared to the contemporary scene. With Alternative Attuali (i.e. Current Alternatives), in fact, the Roman art critic was proposing on a large scale a new kind of collective exhibition, already experimented in a smaller size in Rome with Possibilità di relazione: not a simple artists' show, but a dialogue, with no merit hierarchies, between different positions (the “alternatives”) aimed at going beyond Informal art. This model of “exhibition-essay”, including an actual debate consigned to the catalogue pages, for the first time applied a form of display which would attempt to put the present situation in a critical (and historical) perspective. -

ALECHINSKY Pierre

The Trinity College Dublin Art Collections Artist: Pierre Alechinsky Title: Boréalité Rouge Medium: lithograph Notes: signed: Alechinsky b.1927, Brussels, Belgium Pierre Alechinsky was a painter, draughtsman, printmaker, film maker, ceramic artist and writer. From 1944 to 1946 he studied book illustration and typography at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture et des Arts Décoratifs in Brussels. In 1947 became a member of the Jeune Peinture Belge group and in this same year, he held his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Lou Cosyn. In 1949 Alechinsky became a key member of the CoBrA art movement which included artists Karel Appel and Asger Jorn. This group was formed in 1948 as a reaction to the French Surrealists and was named for the cities its founding artists came from – Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam. CoBrA artists preferred their work to be spontaneous and direct, experimental, colourful, expressive and took inspiration from folk art and children’s literature. While a member of the CoBrA group, Alechinsky focused mainly on organising exhibitions and running their eponymous magazine. When the group was disbanded in 1951 Alechinsky decided to go on to study engraving in Paris. In the mid-1950s, Alechinsky moved to Japan for a time to study the art of calligraphy, making a film on the subject, Calligraphie japonaise, in 1956. Alechinsky was particularly interested in the way these calligraphers worked; they placed their paper on the floor and bent to it from a standing position, in this sense, they used their whole body in the process of calligraphy. Alechinsky’s time spent in Japan had a lasting influence on his style of painting. -

Moderne Kunst

Moderne kunst Schilderijen, sculpturen, etsen en lithografieën van o.a.: ARMAN, DELVAUX, VENET, BOGAERT, ALECHINSKY, RAVEEL, FABRE en nog vele anderen. Startdatum Friday 19 April 2019 10:00 Bezichtiging Friday April 19 2019 from 15:00 till 17:00 BE-2630 Aartselaar, Helststraat 47 Friday April 26 2019 from 15:00 till 17:00 BE-2630 Aartselaar, Helststraat 47 Einddatum Dinsdag 30 april 2019 vanaf 20:00 Afgifte Tuesday May 07 2019 from 14:00 till 16:00 BE-2630 Aartselaar, Helststraat 47 Online bidding only! Voor meer informatie en voorwaarden: www.moyersoen.be 30/04/2019 06:00 Kavel Omschrijving Openingsbod 1 JAVACHEFF CHRISTO -Wrapped Reichstag-offset lithograph signed in 600€ pencil, Dimensions approximately: 1110 x 1240 mm, Location: Upstairs 2 JULES LISMONDE -Lithography on frock nacré paper-signed and 120€ numbered on 100 copies, Dimensions approximately: 940 x 720 mm, Location: Upstairs 3 KAREL APPEL -Look live game with karel-Silkscreen from the series-Dated 240€ 1977 and numbered, Dimensions approximately: 830 x 830 mm, Location: Upstairs 4 PIERRE ALECHINSKY -Composition in black and red, 360€ Dimensions approximately: 880 x 680 mm, Extra information: Very typical and strong etching and aquatint in colors are known and sought after on handmade paper. This work is signed in pencil and numbered to 90 copies. Professionally framed with several passe-partouts. Pierre Alechinsky is the only artist still alive COBRA . His works are sought after. In 1949 he joined the Cobra Group. With Christian Dotremont Alechinsky was the driving force behind the Belgian Division of Cobra movement, Location: Upstairs 5 BERNAR VENET -Gribs Exceptionally beautiful Etching--aquatint and 840€ carborendum-signed and numbered on 30 copies, Prof. -

PIERRE ALECHINSKY: a PRINT RETROSPECTIVE, an Exhibition Exploring

The Museum of Modern Art 50th Anniversary FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE no NO. 33 MASTER PRINTS BY ALECHINSKY TO OPEN AT MUSEUM PIERRE ALECHINSKY: A PRINT RETROSPECTIVE, an exhibition exploring this contemporary artist's work in the print media, will open in the third-floor Sachs Galleries at The Museum of Modern Art on June 11, 1981. Organized by Riva Castleman, Director, and Audrey Isselbacher, Assistant Curator in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, with the co operation of Mr. Alechinsky and Yves Riviere, the exhibition will remain on view through August 11, 1981. A selection of 85 works drawn almost entirely from the Museum's col lection and spanning every phase of Alechinsky's career from his first print made in 1946 to the present, comprises the retrospective. Pierre Alechinsky has devoted more energy, technical skill, imagination and patience to the print media than perhaps any other contemporary artist. The Belgian-born artist has created some 950 works in various print media. Today, according to Riva Castleman, "he continues to retrieve from his crowded past and bustling present the astonishing images that inhabit his prints." It is Alechinsky's seemingly insatiable hunger for experiment and experience that makes his works so vital and vivid. Pierre Alechinsky, who was born in Brussels in 1927, began to make prints as a student at La Cambre, the Belgian national college of archi tecture and decorative arts. While he was there he experimented in all the print media he would later use: linoleum cut, woodcut, etching and continued/ 11 West .53 Street, New York, NY 10019,212-956 6100 Coble: Modemort NO.