82 Land Use and Land Cover Changes Along the Shoreline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Addison Bay, 64 Advanced Sails, 351

FL07index.qxp 12/7/2007 2:31 PM Page 545 Index A Big Marco Pass, 87 Big Marco River, 64, 84-86 Addison Bay, 64 Big McPherson Bayou, 419, 427 Advanced Sails, 351 Big Sarasota Pass, 265-66, 262 Alafia River, 377-80, 389-90 Bimini Basin, 137, 153-54 Allen Creek, 395-96, 400 Bird Island (off Alafia River), 378-79 Alligator Creek (Punta Gorda), 209-10, Bird Key Yacht Club, 274-75 217 Bishop Harbor, 368 Alligator Point Yacht Basin, 536, 542 Blackburn Bay, 254, 260 American Marina, 494 Blackburn Point Marina, 254 Anclote Harbors Marina, 476, 483 Bleu Provence Restaurant, 78 Anclote Isles Marina, 476-77, 483 Blind Pass Inlet, 420 Anclote Key, 467-69, 471 Blind Pass Marina, 420, 428 Anclote River, 472-84 Boca Bistro Harbor Lights, 192 Anclote Village Marina, 473-74 Boca Ciega Bay, 409-28 Anna Maria Island, 287 Boca Ciega Yacht Club, 412, 423 Anna Maria Sound, 286-88 Boca Grande, 179-90 Apollo Beach, 370-72, 376-77 Boca Grande Bakery, 181 Aripeka, 495-96 Boca Grande Bayou, 188-89, 200 Atsena Otie Key, 514 Boca Grande Lighthouse, 184-85 Boca Grande Lighthouse Museum, 179 Boca Grande Marina, 185-87, 200 B Boca Grande Outfitters, 181 Boca Grande Pass, 178-79, 199-200 Bahia Beach, 369-70, 374-75 Bokeelia Island, 170-71, 197 Barnacle Phil’s Restaurant, 167-68, 196 Bowlees Creek, 278, 297 Barron River, 44-47, 54-55 Boyd Hill Nature Trail, 346 Bay Pines Marina, 430, 440 Braden River, 326 Bayou Grande, 359-60, 365 Bradenton, 317-21, 329-30 Best Western Yacht Harbor Inn, 451 Bradenton Beach Marina, 284, 300 Big Bayou, 345, 362-63 Bradenton Yacht Club, 315-16, -

Compilation of Anchorages in SW Florida

Compilation of Anchorages in SW Florida Document is a compilation of information found from cruisers net and Florida Sea grant publications. Revised 1-2015 CAPE SABLE TO OTTER LIDO KEY ANCHORAGES (Armands circle) CONTENTS 1. Cape Sable Anchorages Lat/Lon: near 25 09.569 North/081 08.623 West...........................................................4 2. Little Shark River Outer Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 19.677 North/081 08.801 West..........................................4 3. Little Shark River Southern Fork Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 19.736 North/081 07.132 West ............................5 4. Little Shark River Upper Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 20.268 North/081 06.983 ..................................................5 5. New Turkey Key Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 38.984 North/081 16.759 West .....................................................6 6. Lumber Key Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 45.627 North/081 22.835 West ............................................................7 7. Jack Daniels Key Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 47.882 North/081 25.931 West....................................................7 8. Kingston Key Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 48.005 North/081 27.011 West ..........................................................8 10. Russell Pass Southern Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 49.917 North/081 26.516 West.........................................9 11. Russell Pass Middle Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 50.303 North/081 26.317 West .......................................... 10 12. Russell Pass Northern Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 50.542 North/081 26.019 West....................................... 11 13. Picnic Key Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 49.278 North/081 29.116 West.......................................................... 12 14. Caxambas Pass Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 54.129 North/081 39.953 West ................................................ 13 15. Coon Key Pass Anchorage Lat/Lon: near 25 54.115 North/081 38.433.......................................................... -

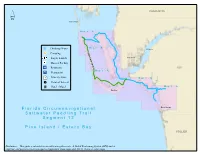

Po ²· I* [T I9

´ CHARLOTTE Boca Grande MM aa pp 11 -- AA op MM aa pp 11 -- BB Drinking Water Ft. Myers a l t[ t Camping e r n Cape Coral Kayak Launch a t e r Shower Facility o u t I* Restroom e LEE MM aa pp 22 -- AA I9 Restaurant ²· Grocery Store MM aa pp 22 -- BB e! Point of Interest l Hotel / Motel MM aa pp 33 -- AA Sanibel Bonita Springs FF ll oo rr ii dd aa CC ii rr cc uu mm nn aa vv ii gg aa tt ii oo nn aa ll SS aa ll tt ww aa tt ee rr PP aa dd dd ll ii nn gg TT rr aa ii ll SS ee gg mm ee nn tt 11 22 PP ii nn ee II ss ll aa nn dd // EE ss tt ee rr oo BB aa yy COLLIER Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Naples Segment 12: Pine Island / Estero BayGASPARILLA SOUND-CHARLOTTE HARBOR AQUATIC PRESERVE Map 1 A 18 6 12 3 Bokeelia Island 6 3 A Jug Creek Cottages 6 e! Jug Creek Point 12 Jug Creek 12 3 6 3 3 ´ 6 Little Bokeelia Island Bokeelia Launch 6 N: 26.6942 I W: -82.1459 12 6 Murdock Point 3 3 Cayo Costa Boat Dock Big Smokehouse Key Mondongo Island 6 N: 26.6857 I W: -82.2455 Big Jim Creek Broken Islands Cayo Costa 3 12 6 State Park 3 3 Darling Key Pineland/Randell Research Center Primo Island N: 26.6593 I W: -82.1529 Useppa Island 3 12 MATLACHA PASS 3 3 6 3 Whoopee Island e! Pineland AQUATIC PRESERVE Cayo Costa 3 12 3 A Part Island l 6 3 12 Pine Island te Cabbage Key rn a Black Key te Bear Key R Coon Key o 3 6 u t e Cove Key Narrows Key 3 6 Wood Key Cat Key 6 6 PINE ISLAND SOUND 3 Little Wood -

Currently the Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems

CRITICALLY ERODED BEACHES IN FLORIDA Updated, June 2009 BUREAU OF BEACHES AND COASTAL SYSTEMS DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION STATE OF FLORIDA Foreword This report provides an inventory of Florida's erosion problem areas fronting on the Atlantic Ocean, Straits of Florida, Gulf of Mexico, and the roughly seventy coastal barrier tidal inlets. The erosion problem areas are classified as either critical or noncritical and county maps and tables are provided to depict the areas designated critically and noncritically eroded. This report is periodically updated to include additions and deletions. A county index is provided on page 13, which includes the date of the last revision. All information is provided for planning purposes only and the user is cautioned to obtain the most recent erosion areas listing available. This report is also available on the following web site: http://www.dep.state.fl.us/beaches/uublications/tech-rut.htm APPROVED BY Michael R. Barnett, P.E., Bureau Chief Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems June, 2009 Introduction In 1986, pursuant to Sections 161.101 and 161.161, Florida Statutes, the Department of Natural Resources, Division of Beaches and Shores (now the Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems) was charged with the responsibility to identify those beaches of the state which are critically eroding and to develop and maintain a comprehensive long-term management plan for their restoration. In 1989, a first list of erosion areas was developed based upon an abbreviated definition of critical erosion. That list included 217.6 miles of critical erosion and another 114.8 miles of noncritical erosion statewide. -

Southwest Coast Red Tide Status Report June 4, 2021

Red Tide Status - Florida Southwest Coast June 04, 2021 Present Status: The red tide organism, Karenia brevis, persists in Southwest Florida. K. brevis was observed at background and low concentrations in two samples collected from Pinellas County, very low to medium concentrations in seven samples collected from Hillsborough County, very low to medium concentrations in 18 samples collected from Manatee County, background concentrations in one sample collected from Sarasota County, background to low concentrations in 15 samples collected from and offshore of Lee County, and background to medium concentrations in 10 samples collected from and offshore of Collier County. Fish kills suspected to be related to red tide were reported over the past week in Pinellas, Manatee, Lee, and Collier counties. For more details, please visit: https://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/health/fish-kills- hotline/. Respiratory irritation was reported over the past week in Pinellas County (6/1 at Pass-a-Grille) and Collier County. For current information, please visit: https://visitbeaches.org/. Forecasts by the USF-FWC Collaboration for Prediction of Red Tides for Pinellas to northern Monroe counties predict northern movement of surface waters and minimal transport of subsurface waters over the next four days. Date Alongshore County Offshore Site Location Collector Collected Inshore Pinellas - 06/01 not present - Clearwater Beach Pier 60 FWRI Grand Bellagio Condo Dock - 06/01 not present - FWRI (Old Tampa Bay) Bravo Drive; S of (Allens - 06/02 not present - -

March 10 2021

Wednesday Update March 10, 2021 Welcome to the bi-weekly Wednesday Update! We'll email the next issue on March 24. By highlighting SCCF's mission to protect and care for Southwest Florida's coastal ecosystems, our updates connect you to nature. Thanks to Mike Puma for this photo of a tri- colored heron (Egretta tricolor) taken on Sanibel. DO YOU HAVE WILDLIFE PHOTOS TO SHARE? Please send your photos to [email protected] to be featured in an upcoming issue. SCCF Partners with Conservancy to Hire Water Analyst To further a commitment to regional water quality and Everglades restoration through a unified front, SCCF and the Naples-based Conservancy of Southwest Florida have partnered to hire a hydrological modeler. “We better fulfill our west coast mission by pooling our resources and streamlining our efforts,” said SCCF CEO Ryan Orgera, Ph.D. “Doing so, we were able to hire a highly qualified data analyst who will move us more efficiently towards water quality solutions.” On March 16, Paul Julian, Ph.D., will begin working as a hydrological modeler for SCCF and the Conservancy of Southwest Florida. The goal of this partnership is to address an important need for modeling expertise and data analysis in Southwest Florida. Work products will be shared between the two non-profits, which have led conservation efforts in Lee and Collier counties for more than five decades. For the past ten years, Julian worked as the Everglades Technical Lead for the Florida Department of Environment Protection (FDEP). In that role, he gained deep understanding of the dynamic Greater Everglades Ecosystem by performing water quality compliance calculations, supporting federal and state restoration planning efforts, developing water quality nutrient models, and mining and analysis of environmental data. -

Testing a Model to Investigate Calusa Salvage of 16Th- and Early-17Th-Century Spanish Shipwrecks

THEY ARE RICH ONLY BY THE SEA: TESTING A MODEL TO INVESTIGATE CALUSA SALVAGE OF 16TH- AND EARLY-17TH-CENTURY SPANISH SHIPWRECKS by Kelsey Marie McGuire B.A., Mercyhurst University, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2014 The thesis of Kelsey McGuire is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ Amy Mitchell-Cook, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Cook, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Marie-Therese Champagne, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ John Worth, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ John R. Bratten, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS If not for the financial, academic, and moral support of dozens of people and research institutions, I could not have seen this project to completion. I would not have taken the first steps without financial support from Dr. Elizabeth Benchley and the UWF Archaeology Institute, the UWF Student Government Association. In addition, this project was supported by a grant from the University of West Florida through the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs. Their generous contributions afforded the opportunity to conduct my historical research in Spain. The trip was also possible through of the logistical support of Karen Mims. Her help at the Archaeology Institute was invaluable then and throughout my time at UWF. Thank you to my research companion, Danielle Dadiego. -

Southwest Florida During the Mississippi Period

2 ......... Southwest Florida during the Mississippi Period WILLIAM H. MARQUARDT AND KAREN J. WALKER This book focuses on the Mississippi period, ca. A.D. 1000 to 1500. In the archaeology of the southeastern United States, "Mississippian" generally means chiefdom-level societies that "practiced a maize-based agriculture, constructed (generally) platform mounds for elite residences and vari- ous corporate and public functions, and shared, to a considerable extent, a common suite of artifact types and styles, particularly in the realm of pottery (usually shell-tempered) and certain symbolic or prestige related artifacts" (Welch and Butler 2006: 2). Often implicit is an assumption that Mississippian chiefdoms represent the most complex cultural develop- ments in t he aboriginal southeastern United States. In southwest Florida, their contemporaries had no maize agriculture, constructed no platform mounds, and made a rather undistinguished pot- tery. Even so, Spaniards who encountered the historic Calusa in the six- teenth century observed a stratified society divided into nobles and com- moners, with hereditary leadership, tributary patronage-clientage that extended throughout south Florida, ritual and military specialists, far- ranging trade, an accomplished and expressive artistic tradition, complex religious beliefs and ritual practices, and effective subsistence practices that supported thousands of people and allowed a sedentary residence pattern (Fontaneda 1973; Hann 1991; Solis de Meras 1964). Furthermore, for nearly two centuries after contact, the Calusa maintained their identity and beliefs, effectively repulsing European attempts to conquer and con- vert them to Christianity, while many southeastern United States chief- doms were in cultural ruin within a few decades (Hann 1991). The Calusa heartland was in the coastal region encompassing Charlotte Harbor, Pine Island Sound, San Carlos Bay, and Estero Bay (figure 2.1). -

Fishing Deep in the Biloxi Marsh

I by Al Rogers Fishing Deep in the Biloxi Marsh nexplored, difficult to reach trout and redfish. The pristine waterways and even harder to navigate, ran through countless passes and into the interior of the Biloxi interior bays before eventually spilling Marsh is believed to be a into even larger nearby bodies of open major factor in the success of fisheries water. from the lower Mississippi River Delta, Spring was in the air. The chill I to Lake Pontchartrain, to the Chandeleur recalled a week earlier was gone. Longer Islands. days warmed the water, driving the Capt. Brian Gagnon looked out over speckled trout and redfish to the surface. the pristine wilderness and inhaleddeeply . In a nearby bay off Bayou Biloxi several It was nearly March, a clear afternoon screeching seagulls hovered over a and this was a long awaited breath of disturbance on the water. In the middle fresh spring air. Seated at the stern of a 14- bays, specks fed aggressively while foot sluff, Gagnon could not have been redfish plowed through the shallows and happier. This was just exactly where the along grass lines. Bay St.Louis,Mississippi native wanted to Gagnon -reached for his chrome be. As far from civilization as he could get. MirrOlure She Dog. Although well worn, "It's hard to believe we haven't seen withdeep slashes from recent battles with or heard another boat or motor in three toothy predators, it was a choice of days," he said. "Three days. When was confidence. Gagnon hit the kill switch, "What'd I tell you?" he asked. -

Long Term Success and Future Approach of the Captiva and Sanibel Islands Beach Renourishment Program

2017 National Conference on Beach Preservation Technology February 8-10, 2017; Stuart, Florida Long Term Success and Future Approach of the Captiva and Sanibel Islands Beach Renourishment Program Thomas P. Pierro, PE, D.CE, Director, CB&I Michelle Pfeiffer, P.E., Senior Project Engineer, CB&I Stephen Keehn, P.E., Senior Coastal Engineer, CB&I Kathleen Rooker, Adminstrator, CEPD, Captiva, FL Acknowledgments CEPD Board Members, Alison Hagerup, Tom Campbell, Bill Stronge A World of Solutions 2016 Annual Conference Fireside Chat Series . Hurricane Hermine . Windshield inspection 9/2/2016 . Beach buffered storm A World of Solutions 1 Captiva Island Erosion Prevention District . The District was established as a beach and shore preservation district June 19, 1959. “Our sole purpose and dedication is to Captiva beach and shore preservation.” – Kathy Rooker, Captiva Island Erosion Prevention District (2017) . Lee County's Beach Management Plan traces its roots to Captiva Island. “Captiva Island was the birthplace of beach nourishment in Lee County.” – Steve Boutelle, Lee County Division of Natural Resources (2014) A World of Solutions 2 Captiva Beach Culture . Captiva Island property owners overwhelming support beach projects. “Its expected and accepted.” – Longtime property owner regarding the beach nourishment projects A World of Solutions 3 Captiva Island . Lee County . Barrier island system . Connected waterways Captiva Pass North Captiva Island Redfish Pass Pine Island Sound Captiva Island Blind Pass Gulf of Mexico Sanibel Island A World of Solutions 4 Project Location Map . Over 50 years of nourishment projects . Limited fill placements in 1961 and 1981; 134 groins . First island-wide nourishment in 1988/89 . Renourished in 1996 and 2005/06 . -

Research Resumes on Useppa Island by Karen Walker and Bill Marquardt

Friends of the Randell Research Center December 2012 • Vol. 11, No. 4 Research Resumes on Useppa Island by Karen Walker and Bill Marquardt In late November, we will return to Useppa Island to resume work in deposits that accumulated there about 3,000 years ago. This work is co-sponsored by the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Randell Research Center (RRC), the Useppa Island Historical Society, and the Useppa Inn and Dock Company. We are grateful to Tim Fitzsimmons and Garfi eld Beckstead of Useppa Island for providing the logistical assistance, lodging, and boat transportation that makes this work possible, and to David and Judy Nutting for permission to work on their property. This work will continue a project initiated in March, 2012, when Useppa residents joined with volunteers from the RRC and archaeologists from the Florida Museum to explore part of Useppa’s Southern Ridge (known locally as the “South Knoll”). One of the most common questions that Useppa passers- Excavations in Useppa’s Southern Ridge, March 2012. by asked us in March was, “Why are you digging at this Pictured (left to right) are John Turck, Ellen Turck, and Bill particular place?” Well, it is not the oldest deposit on Useppa, Marquardt. (Photo by K. Walker). nor are we fi nding extraordinary artifacts, but we do think the deposits left there by ancient Native Americans may help us fi ll in gaps in our understanding of climate changes and how to the people who lived on Calusa Ridge about 1,000 years the Indian people adapted to them. -

The Changing Face of Commercial Fishing in Charlotte Harbor: Triumph of Ice Over Salt Theodore B

The Changing Face of Commercial Fishing In Charlotte Harbor: Triumph of Ice over Salt Theodore B. VanItallie Harbor Habitat “Fishermen go where the fish are” and, by all accounts, the fish populations of Charlotte Harbor in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries were extraordinarily abundant. One of Florida's principal estuaries, the harbor in its pristine state must have provided an ideal habitat for many species of fish. The photic zone—a relatively thin layer of water that can be penetrated by light—is an ocean's primary production area. In the photic zone, growth rate depends on the intensity of light and the supply of available nutrients. When its waters are sufficiently clear and placid, Charlotte Harbor is shallow enough to permit transmission of abundant light to the phytoplankton (minute plant life) and to the sea grasses that provide a habitat favorable to fish. Three major rivers, the Myakka, Peace, and Caloosahatchee, flow into the estuarine system, delivering the nutrients needed to replace those used up by the harbor's teeming marine life. These freshwater streams also provide the zones of reduced salinity that some fish, especially juvenile forms, require. Unfortunately, fish-nursery conditions in Charlotte Harbor are not as favorable as they once were. Ecologists report that, overall, the Harbor's sea-grass meadows declined by about 29% between 1945 and 1982. A little more than half of this reduction was found in Pine Island Sound, Matlacha Pass, and San Carlos Bay. An adverse impact on the estuary's sea grass—probably transient— appears to have resulted from dredging associated with construction of the Intracoastal Waterway and the Sanibel Causeway.