1990: Oakland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Geometric Generalizations of the Tonnetz and Their Relation To

November 22, 2017 12:45 ws-rv9x6 Book Title yustTonnetzSub page 1 Chapter 1 Geometric Generalizations of the Tonnetz and their Relation to Fourier Phases Spaces Jason Yust Boston University School of Music, 855 Comm. Ave., Boston, MA, 02215 [email protected] Some recent work on generalized Tonnetze has examined the topologies resulting from Richard Cohn's common-tone based formulation, while Tymoczko has reformulated the Tonnetz as a network of voice-leading re- lationships and investigated the resulting geometries. This paper adopts the original common-tone based formulation and takes a geometrical ap- proach, showing that Tonnetze can always be realized in toroidal spaces, and that the resulting spaces always correspond to one of the possible Fourier phase spaces. We can therefore use the DFT to optimize the given Tonnetz to the space (or vice-versa). I interpret two-dimensional Tonnetze as triangulations of the 2-torus into regions associated with the representatives of a single trichord type. The natural generalization to three dimensions is therefore a triangulation of the 3-torus. This means that a three-dimensional Tonnetze is, in the general case, a network of three tetrachord-types related by shared trichordal subsets. Other Ton- netze that have been proposed with bounded or otherwise non-toroidal topologies, including Tymoczko's voice-leading Tonnetze, can be under- stood as the embedding of the toroidal Tonnetze in other spaces, or as foldings of toroidal Tonnetze with duplicated interval types. 1. Formulations of the Tonnetz The Tonnetz originated in nineteenth-century German harmonic theory as a network of pitch classes connected by consonant intervals. -

OCT 1 2 2001 90; OCT RE LIBRARIES Hyperscore: a New Approach to Interactive, Computer-Generated Music by Mary Farbood

Hyperscore: A New Approach to Interactive, Computer-Generated Music by Mary Farbood A.B. Music Harvard University (1997) Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2001 @ Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2001. All rights reserved. A u th o r ........................................................................ .......... Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning September 1, 2001 Certified by .......................... .. \ . .. Tod Machover essor of Music and Media Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ..................... 17 d B. Lippman Chair, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Program in Media Arts and Sciences MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OCT 1 2 2001 90; OCT RE LIBRARIES Hyperscore: A New Approach to Interactive, Computer-Generated Music by Mary Farbood Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning on September 1, 2001, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences Abstract This thesis discusses the design and implementation of Hyperscore, a computer- assisted composition system intended for users of all musical backgrounds. Hyper- score presents a unique graphical interface which takes input in the form of freehand drawing. The strokes in the drawing are mapped to structural and gestural elements in the music, allowing the user to describe the large scale-structure of a piece vi- sually. Hyperscore's graphical notation also enables the depiction of musical ideas on a detailed level. Additional annotations around a main curve indicate the place- ment and emphasis of selected motives. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill?

DAVID DREW Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill? The pretexts for the present paper are the author's essays >Der T#g der Ver heissung and the Prophecies of jeremiah<, Tempo, 206 (October 1998), 11- 20, and >Der T#g der Verheissung: Weill at the Crossroads<, 1impo, 208 (April 1999), 335-50. As suggested in the preface to the second essay, the paper is intended to function both as a free-standing entity and as an extended bridge between the last section of the earlier essay and the first section of its successor. According to Meyer Weisgal's detailed account of the origins of The Eter nal Road, Reinhardt had no inkling of his plans until their November 1933 meeting in Paris.1 Weisgal began by outlining the idea of a biblical drama that would for the first time evoke the Old Testan1ent in all its breadth rather than in isolated episodes. At the end of his account, according to Weisgal, Reinhardt sat motionless and in silence before saying »very sim ply<< »But who will be the author of this biblical play and who will write the mu sic?<< . »You are the master<< , I said, ••It is up to you to select them<<. Again there was a long uncomfortable pause and Reinhardt said that he would ask Franz Werfel and Kurt Weill to collaborate with him. With or without prior notice2, the problems inherent in Weisgal's com mission were so complex that Reinhardt would have had good reason for Meyer W. Weisgal, >Beginnings of The Eternal Road<, in: T"he Etemal Road (New York 1937 - programme-book for the production by MWW and Crosby Gaige at the Man hattan Opera House), pp. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

1St First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern

1st First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern. arr. Ozzie Westley (1944) BPC The Barberpole Cat Program and Song Book. (1987) BB1 Barber Shop Ballads: a Book of Close Harmony. ed. Sigmund Spaeth (1925) BB2 Barber Shop Ballads and How to Sing Them. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1940) CBB Barber Shop Ballads. (Cole's Universal Library; CUL no. 2) arr. Ozzie Westley (1943?) BC Barber Shop Classics ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1946) BH Barber Shop Harmony: a Collection of New and Old Favorites For Male Quartets. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1942) BM1 Barber Shop Memories, No. 1, arr. Hugo Frey (1949) BM2 Barber Shop Memories, No. 2, arr. Hugo Frey (1951) BM3 Barber Shop Memories, No. 3, arr, Hugo Frey (1975) BP1 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 1. (1946) BP2 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 2. (1952) BP Barbershop Potpourri. (1985) BSQU Barber Shop Quartet Unforgettables, John L. Haag (1972) BSF Barber Shop Song Fest Folio. arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1948) BSS Barber Shop Songs and "Swipes." arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1946) BSS2 Barber Shop Souvenirs, for Male Quartets. New York: M. Witmark (1952) BOB The Best of Barbershop. (1986) BBB Bourne Barbershop Blockbusters (1970) BB Bourne Best Barbershop (1970) CH Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle (1936) CHR Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle. Revised (1941) CH1 Close Harmony: Male Quartets, Ballads and Funnies with Barber Shop Chords. arr. George Shackley (1925) CHB "Close Harmony" Ballads, for Male Quartets. (1952) CHS Close Harmony Songs (Sacred-Secular-Spirituals - arr. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

APPENDIX 1 Inventories of Sources of English Solo Lute Music

408/2 APPENDIX 1 Inventories of sources of English solo lute music Editorial Policy................................................................279 408/2.............................................................................282 2764(2) ..........................................................................290 4900..............................................................................294 6402..............................................................................296 31392 ............................................................................298 41498 ............................................................................305 60577 ............................................................................306 Andrea............................................................................308 Ballet.............................................................................310 Barley 1596.....................................................................318 Board .............................................................................321 Brogyntyn.......................................................................337 Cosens...........................................................................342 Dallis.............................................................................349 Danyel 1606....................................................................364 Dd.2.11..........................................................................365 Dd.3.18..........................................................................385 -

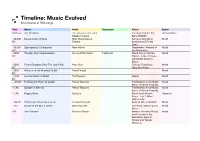

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

The Collegium Musicum the Madrigal Singers

The School ofMusic , presents the 57th program ofthe 1989-90 season c,'19qO 2. -2-7 The Collegium Musicum Margriet Tmdemans, Director The Madrigal Singers Joan Catoni Conlon. Director .. '..,-' ' "LaBella Venezia" Diversity of styles from La Serenissima February 27, 1990, 8:00 PM Meany 1beater " I -- --......~. r' I D~lI,(001 c fk.s 'fF Ir t9 0 2 11.(,,;03 Thus. amidst her angry tears, she lifted her voice to heaven. In this way in the hearts oflovers does Love Program mixflames and ice. Ca.~"'7*1lr(&02A Cynthia Beiunen. mezzo-soprano Dessus Ie marebe d'Arras (1528) .......... ADRIAN WIU.AERT (C.1490-1562) At the market (me"ily. merrily we play). I encountered a Spaniard (merrily ...). He said, 'Usten. maid,' Hor care canzonette (1584) ......................•CI..AUDIO MONTEVERDI (merrily...) 'I will give you silver' (merrily...). Dear camonets. go swiftly and surely. Ricercar declmo (Venice. 1559) ................................WILLAERT without saying a word. to Idss her hand... r Sweet camonets. go only to one...begging her pardon... Maledetto (1632) .................................CI..AUDIO MONTEVERDI Adoramus te (1620) ....................CI..AUDIO MONTEVERDI (1567-1643) (Lament ofOlympia. abandoned by her lover on a We adore you. 0 Christ. and we bless'JOu./Or by your desert island}Cursed one! I love with afaitlt/ul. burn.ing passion. priceless blood, you have redeemed us. Have mercy upon yet I am a river oftorment. Love's ~ows pierce us. me. yet I am disarmed. You dismiss the fire ofmy love! Laurie Hungerford Flint, soprano Cantate Domino (1620) ........................... CI..AUDIO MONTEVERDI Sing to the Lord a new song. a bless G04 s name, who has made miracles to happen.