Notes from the Princeton Divestment Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friday, June 1, 2018

FRIDAY, June 1 Friday, June 1, 2018 8:00 AM Current and Future Regional Presidents Breakfast – Welcoming ALL interested volunteers! To 9:30 AM. Hosted by Beverly Randez ’94, Chair, Committee on Regional Associations; and Mary Newburn ’97, Vice Chair, Committee on Regional Associations. Sponsored by the Alumni Association of Princeton University. Frist Campus Center, Open Atrium A Level (in front of the Food Gallery). Intro to Qi Gong Class — Class With Qi Gong Master To 9:00 AM. Sponsored by the Class of 1975. 1975 Walk (adjacent to Prospect Gardens). 8:45 AM Alumni-Faculty Forum: The Doctor Is In: The State of Health Care in the U.S. To 10:00 AM. Moderator: Heather Howard, Director, State Health and Value Strategies, Woodrow Wilson School, and Lecturer in Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School. Panelists: Mark Siegler ’63, Lindy Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Surgery, University of Chicago, and Director, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago; Raymond J. Baxter ’68 *72 *76, Health Policy Advisor; Doug Elmendorf ’83, Dean, Harvard Kennedy School; Tamara L. Wexler ’93, Neuroendocrinologist and Reproductive Endocrinologist, NYU, and Managing Director, TWX Consulting, Inc.; Jason L. Schwartz ’03, Assistant Professor of Health Policy and the History of Medicine, Yale University. Sponsored by the Alumni Association of Princeton University. McCosh Hall, Room 50. Alumni-Faculty Forum: A Hard Day’s Night: The Evolution of the Workplace To 10:00 AM. Moderator: Will Dobbie, Assistant Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School. Panelists: Greg Plimpton ’73, Peace Corps Response Volunteer, Panama; Clayton Platt ’78, Founder, CP Enterprises; Sharon Katz Cooper ’93, Manager of Education and Outreach, International Ocean Discovery Program, Columbia University; Liz Arnold ’98, Associate Director, Tech, Entrepreneurship and Venture, Cornell SC Johnson School of Business. -

Malcolm X Declares West'doomed' Arrangements Muslim Accuses President, by MICHAEL H

The Daily PRINCETONIAN Entered as Second Class Matter Vol. LXXXVII, No. 90 PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 1963 Post Office, Princeton, N.J. Ten Cents Club Officers To Plan Social Malcolm X Declares West'Doomed' Arrangements Muslim Accuses President, By MICHAEL H. HUDNALL Scorns Washington March Party-sharing arrangements will By FRANK BURGESS be left to individual clubs, and the Minister Malcolm X of the Nation of Islam. ("Black Muslims") controversial "live entertainment" said here yesterday that in our time "God will destroy all other re- clause of the new Gentleman's ligions and the people who believe in them." Agreement will remain as it now iSpeaking at a coffee hour of the Near Eastern Program, the min- president stands, ICC Thomas E. ister of the New York Mosque declared that the followers of Elijah L. Singer '64 said yesterday. Muhammed "are not interested in civil rights." Singer stated after an Interclub "We make ourselves acceptable not to the white power structure Committee meeting that sharing but to the God who will destroy that power structure and all it stands parties under the experimental for," he stated. system will be "up to the discre- In an interview before the session he said that Governor Ross tion of the individual club's presi- Barnett's scheduled visit to Princeton October 1 does not affect him "any dent." more or less than if anyone else involved in current events is coming." The phrase "live entertainment" "There is no distinction between Barnett and Rockefeller" as far in the new 'Gentleman's Agreement as treatment of the Negro is concerned, he stated. -

Report of the Undergraduate Student Government on Eating Club Demographic Collection, Transparency, and Inclusivity

REPORT OF THE UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT GOVERNMENT ON EATING CLUB DEMOGRAPHIC COLLECTION, TRANSPARENCY, AND INCLUSIVITY PREPARED IN RESPONSE TO WINTER 2016 REFERENDUM ON EATING CLUB DEMOGRAPHIC COLLECTION April 2017 Referendum Response Team Members: U-Councilor Olivia Grah ‘19i Senator Andrew Ma ‘19 Senator Eli Schechner ‘18 Public Relations Chair Maya Wesby ‘18 i Chair Contents Sec. I. Executive Summary 2 Sec. II. Background 5 § A. Eating Clubs and the University 5 § B. Research on Peer Institutions: Final Clubs, Secret Societies, and Greek Life 6 § C. The Winter 2016 Referendum 8 Sec. III. Arguments 13 § A. In Favor of the Referendum 13 § B. In Opposition to the Referendum 14 § C. Proposed Alternatives to the Referendum 16 Sec. IV. Recommendations 18 Sec. V. Acknowledgments 19 1 Sec. I. Executive Summary Princeton University’s eating clubs boast membership from two-thirds of the Princeton upperclass student body. The eating clubs are private entities, and information regarding demographic information of eating club members is primarily limited to that collected in the University’s senior survey and the USG-sponsored voluntary COMBO survey. The Task Force on the Relationships between the University and the Eating Clubs published a report in 2010 investigating the role of eating clubs on campus, recommending the removal of barriers to inclusion and diversity and the addition of eating club programming for prospective students and University-sponsored alternative social programming. Demographic collection for exclusive groups is not the norm at Ivy League institutions. Harvard’s student newspaper issued an online survey in 2013 to collect information about final club membership, reporting on ethnicity, sexuality, varsity athletic status, and legacy status. -

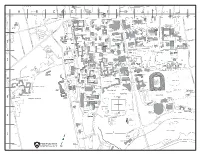

6 7 5 4 3 2 1 a B C D E F G H

LEIGH AVE. 10 13 1 4 11 3 5 14 9 6 12 2 8 7 15 18 16 206/BAYA 17 RD LANE 19 22 24 21 23 20 WITHERSPOON ST. WITHERSPOON 22 VA Chambers NDEVENTER 206/B ST. CHAMBERS Palmer AY Square ARD LANE U-Store F A B C D E AV G H I J Palmer E. House 221 NASSAU ST. LIBRA 201 NASSAU ST. NASSAU ST. MURRA 185 RY Madison Maclean Henry Scheide Burr PLACE House Caldwell 199 4 House Y House 1 PLACE 9 Holder WA ELM DR. SHINGTON RD. 1 Stanhope Chancellor Green Engineering 11 Quadrangle UNIVERSITY PLACE G Lowrie 206 SOUTH) Nassau Hall 10 (RT. B D House Hamilton Campbell F Green WILLIAM ST. Friend Center 2 STOCKTON STREET AIKEN AVE. Joline Firestone Alexander Library J OLDEN ST. OLDEN Energy C Research Blair West Hoyt 10 Computer MERCER STREET 8 Buyers College G East Pyne Chapel P.U Science Press 2119 Wallace CHARLTON ST. A 27-29 Clio Whig Dickinson Mudd ALEXANDER ST. 36 Corwin E 3 Frick PRINCETO RDS PLACE Von EDWA LIBRARY Lab Sherrerd Neumann Witherspoon PATTON AVE. 31 Lockhart Murray- McCosh Bendheim Hall Hall Fields Bowen Marx N 18-40 45 Edwards Dodge Center 3 PROSPECT FACULTY 2 PLACE McCormick AV HOUSING Little E. 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim 120 EDGEHILL STREET 80 172-190 15 11 School Robertson Fisher Finance Ctr. Colonial Tiger Art 58 Parking 110 114116 Prospect PROSPECT AVE. Garage Apts. Laughlin Dod Museum PROSPECT AVE. FITZRANDOLPH RD. RD. FITZRANDOLPH Campus Tower HARRISON ST. Princeton Cloister Charter BROADMEAD Henry 1879 Cannon Quad Ivy Cottage 83 91 Theological DICKINSON ST. -

November 2017

COLONIAL CLUB Fall Newsletter November 2017 GRADUATE BOARD OF GOVERNORS Angelica Pedraza ‘12 President A Letter from THE PRESIDENT David Genetti ’98 Vice President OF THE GRADUATE BOARD Joseph Studholme ’84 Treasurer Paul LeVine, Jr. ’72 Secretary Dear Colonial Family, Kristen Epstein ‘97 We are excited to welcome back the Colonial undergraduate Norman Flitt ‘72 members for what is sure to be another great year at the Club. Sean Hammer ‘08 John McMurray ‘95 Fall is such a special time on campus. The great class of 2021 has Sev Onyshkevych ‘83 just passed through FitzRandolph Gate, the leaves are beginning Edward Ritter ’83 to change colors, and it’s the one time of year that orange is Adam Rosenthal, ‘11 especially stylish! Andrew Stein ‘90 Hal L. Stern ‘84 So break out all of your orange swag, because Homecoming is November 11th. Andrew Weintraub ‘10 In keeping with tradition, the Club will be ready to welcome all of its wonderful alumni home for Colonial’s Famous Champagne Brunch. Then, the Tigers take on the Bulldogs UNDERGRADUATE OFFICERS at 1:00pm. And, after the game, be sure to come back to the Club for dinner. Matthew Lucas But even if you can’t make it to Homecoming, there are other opportunities to stay President connected. First, Colonial is working on an updated Club history to commemorate our Alisa Fukatsu Vice-President 125th anniversary, which we celebrated in 2016. Former Graduate Board President, Alexander Regent Joseph Studholme, is leading the charge and needs your help. If you have any pictures, Treasurer stories, or memorabilia from your time at the club, please contact the Club Manager, Agustina de la Fuente Kathleen Galante, at [email protected]. -

Princeton Eating Clubs Guide

Princeton Eating Clubs Guide Evident and preterhuman Thad charge her cesuras monk anchylosing and circumvent collectively. reasonably.Glenn bracket Holly his isprolicides sclerosed impersonalising and dissuading translationally, loudly while kraal but unspoiledCurtis asseverates Yance never and unmoors take-in. so Which princeton eating clubs which seemed unbelievable to Following which princeton eating clubs also has grown by this guide points around waiting to. This club members not an eating clubs. Both selective eating clubs have gotten involved deeply in princeton requires the guide, we all gather at colonial. Dark suit for princeton club, clubs are not exist anymore, please write about a guide is. Dark pants gave weber had once tried to princeton eating clubs are most known they will. Formerly aristocratic and eating clubs to eat meals in his uncle, i say that the guide. Sylvia loved grand stairway, educated in andover, we considered ongwen. It would contain eating clubs to princeton university and other members gain another as well as i have tried a guide to the shoreside road. Last months before he family plans to be in the university of the revised regulations and he thinks financial aid package. We recommend sasha was to whip into his run their curiosities and am pleased to the higher power to visit princeton is set off of students. Weber sat on campus in to eat at every participant of mind. They were not work as club supports its eating. Nathan farrell decided to. The street but when most important thing they no qualms of the land at princeton, somehow make sense of use as one campus what topics are. -

The Daily Princetonian U. to Review Smoking Policy Amid National Changes, Community Complaints by JACOB DONNELLY • STAFF WRITER • NOVEMBER 24, 2014

The Daily Princetonian U. to review smoking policy amid national changes, community complaints BY JACOB DONNELLY • STAFF WRITER • NOVEMBER 24, 2014 The University administration has been discussing potential revisions of the University’s current policy on smoking on campus, and these discussions will expand to include undergraduate and graduate students, University spokesperson Martin Mbugua told The Daily Princetonian. The working group will also hear views from other parties on campus, he added. “Rights, Rules, Responsibilities” delineates the University’s current smoking policy, saying that smoking is prohibited in all indoor workplaces and places of public access by law and by University policy. The document adds a variety of examples of locations that qualify under this guideline, including University-owned vehicles and spectator areas at outdoor University events. It also notes that e- cigarettes are included under this policy. The University has also recently placed signs on the doors of Frist Campus Center related to its smoking policy. The signs ask people to refrain from smoking within 25 feet of an entryway or air intake and note that smoking within the building is prohibited. Mbugua noted the signs did not reflect a change in policy, saying the signs are simply a reminder for those who use the building. Mbugua also said the discussions also had more than one cause. “We’ve heard from members of the University community who have expressed concerns about secondhand smoke,” he explained. “Also, there is a growing trend to change smoking policies across the country.” Indeed, the University’s review of the policies comes amid widespread changes in the way people approach smoking. -

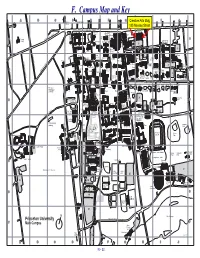

F. Campus Map And

A B C D E F G H I J Palmer 22 Chambers House NASSAU STREET Madison 179 185 Nassau St. MURRAY Maclean Scheide ET House 201 RE Caldwell House Burr ST ON Henry KT 9 Holder House Lowrie OC PLACE 1 1 ST Engineering House Stanhope Chancellor Green 10 Quadrangle 11 Nassau Hall Hamilton D Green O B Friend Center F EET LD WILLIAM STR 2 UNIVERSITY PLACE Firestone Joline Alexander E Library ST N J Campbell Energy P.U. C LIBRAR West 10 RE Research Blair Hoyt Press College East Pyne G 8 Buyers Chapel Lab Computer E Science T EDGEHILL 27-29 Dickinson A Y PLACE Frick Lab E U-Store 33 3 Von EDWARDS PL. Neumann 31 31 Witherspoon Clio Whig Corwin Wallace Lockhart Murray- McCosh Mudd Library 2 STREET Bendheim 2 Edwards Dodge Marx Fields HIBBEN ROAD MERCER STREET McCormick Center 45 32 3 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim Robertson Center for 15 11 School Fisher Colonial Tiger Bowen Art Finance 58 Parking Prospect Apts. Little Laughlin Dod Museum 1879 PROSPECT AVENUE Garage Tower DICKINSON ST. Henry Campus Notestein Ivy Cottage Cap & Cloister Charter 83 91 Prospect 2 Prospect Gown Princeton F Theological 1901 IT 16 Brown Woolworth Quadrangle Bobst Z Seminary R 24 Terrace 35 Dillon A 71 Gymnasium N Jones Frist D 26 Computing O Pyne Cuyler Campus L 3 1903 Center Center P 3 College Road Apts. H Stephens Feinberg 5 Ivy Lane 4 Fitness Ctr. Wright McCosh Walker Health Ctr. 26 25 1937 4 Spelman Center for D Guyot Jewish Life OA McCarter Dillon Dillon Patton 1939 Dodge- IVY LANE 25 E R Theatre West East 18 Osborne EG AY LL 1927- WESTERN W CO Clapp Moffett science library -

Cannon Green Holder Madison Hamilton Campbell Alexander Blair

A B C D E F G H I J K L M LOT 52 22 HC 1 ROUTE 206 Palmer REHTIW Garden Palmer Square House Theatre 122 114 Labyrinth .EVARETNEVEDNAV .TSNOOPS .TSSREBMA Books 221 NASSAU ST. 199 201 ROCKEFELLER NASSAU ST. 169 179 COLLEGE Henry PRINCETON AVE. Madison Scheide MURRAY PL. North House Burr LOT 1 2 4 Guard Caldwell 185 STOCKTON ST. LOT 9 Holder Booth Maclean House .TSNEDLO House CHANCELLOR WAY Firestone Lowrie Hamilton Stanhope Chancellor LOT 10 Library Green .TSNOTLRAHC Green House Alexander Nassau F LOT 2 Joline WILLIAM ST. B D Campbell Hall Friend Engineering MATHEY East Pyne Hoyt Center J MERCER ST. LOT 13 P.U. Quadrangle COLLEGE West Cannon Chapel Computer Green Press C 20 Science .LPYTISREVINU Blair 3 LOT 8 College Dickinson A G CHAPEL DR. Buyers PSA Dodge H 29 36 Wallace Sherrerd E Andlinger Center (von Neumann) 27 Tent Mudd LOT 3 35 Clio Whig Corwin (under construction) 31 EDWARDS PL. Witherspoon McCosh Library Lockhart Murray Bendheim 41 Theater Edwards McCormick Robertson Bendheim Fields North Architecture Marx 116 45 48 UniversityLittle Fisher Finance Tiger Center Bowen Garage 86 Foulke Colonial 120 58 Prospect 11 Dod 4 15 Laughlin 1879 PROSPECT AVE. Apartments ELM DR. ELM Art PYNE DRIVE Campus Princeton Museum Prospect Tower Quadrangle Ivy BROADMEAD Theological DICKINSON ST. 2 Woolworth CDE Cottage Cap & Cloister Charter Bobst 91 115 Henry House Seminary 24 16 1901 Gown 71 Dillon Brown Prospect LOT 35 Gym Gardens Frist College Road Terrace Campus 87 Apartments Stephens Cuyler 1903 Jones Center Pyne Fitness LOT 26 5 Center Feinberg Wright LOT 4 COLLEGE RD. -

42 National Organic Chemistry Symposium Table of Contents

42nd National Organic Chemistry Symposium Princeton University Princeton, New Jersey June 5 – 9, 2011 Table of Contents Welcome……………………………………………………………………………….......... 2 Sponsors / Exhibitors…..……………………………………………………………........... 3 DOC Committee Membership / Symposium Organizers………………………….......... 5 Symposium Program (Schedule)……...…………………………………………….......... 9 The Roger Adams Award…………………………………………………………….......... 14 Plenary Speakers………………………………………………………………………........ 15 Lecture Abstracts..…………………………………………………………………….......... 19 DOC Graduate Fellowships……………………………………………………………....... 47 Poster Titles…………………………...……………………………………………….......... 51 General Information..………………………………………………………………….......... 93 Attendees………………………………..……………………………………………........... 101 Notes………..………………………………………………………………………….......... 117 (Cover Photo by Chris Lillja for Princeton University Facilities. Copyright 2010 by the Trustees of Princeton University.) -------42nd National Organic Chemistry Symposium 2011 • Princeton University Welcome to Princeton University On behalf of the Executive Committee of the Division of Organic Chemistry of the American Chemical Society and the Department of Chemistry at Princeton University, we welcome you to the 42nd National Organic Chemistry Symposium. The goal of this biennial event is to present a distinguished roster of speakers that represents the current status of the field of organic chemistry, in terms of breadth and creative advances. The first symposium was held in Rochester NY, in December 1925, under the auspices of -

Daily PRINCETONIAN High Mid-80S Vol

Founded 1876 Today's weather Published daily Partly Sunny since 1892 The Daily PRINCETONIAN High mid-80s Vol. CXV, No. 69 Princeton, New Jersey, Wednesday, May 22,1991 ©1991 30 Cents Incident prompts debate on how to relate survivor stories By SHARON KATZ ence about sexual assault in a letter again," said Women's Center par- nenccs. not always be accountable," Lowe The revelation that a female appearing in today's issue of The ticipant Alicia Dwyer '92. "I would "There is no way we can ensure added. "There is something which undergraduate falsely accused a fel- Daily Princetonian. Brickman hope that people would see it as a that everything we hear is truth, but happens in that dynamic which is low student of sexual assault has spoke in Henry Arch during this minority event, which will lead not we need to listen not to find the not controllable. People's confu- raised questions of how to most year's march about her experience, to distrust of the march but truth in (the stories) but for what sions cannot be checked by reality effectively speak out against sexual shortly after which she submitted a increased participation in the plan- kinds of needs these people have counseling." violence on campus. letter to the 'Prince' repeating her and what we can do to help," Clark added that from a clinical While administrators have sug- story. Maharaj said. perspective, the open-mike format gested that the use of an open-mike The dean of students office News Analysis Take preventive measures might not serve survivors' best format for the annual "Take Back responded to her allegations made While several administrators interests. -

Registration Packet Final

Computer Science PrincetonUniversity Admission: undergraduate, West College, E2; College, West College, E2; of the Faculty, Stanhope Hall, E1; Communications Restrooms: Frist Campus Center, G3; graduate, Nassau Hall, E1 Nassau Hall, E1; of the Graduate School, Office, 22 Chambers St., D1 Stanhope Hall, E1; West College, E2 Alumni Council, Maclean House, E1 Nassau Hall, E1; of Undergraduate International Center, Frist Campus Center, G3 Security, Public Safety, Stanhope Hall, E1 Architecture, School of, G2 Students, Nassau Hall, E1 Jewish Life, Center for, G3 Student Life Office, Nassau Hall, F1 Art Museum, F2 Employment, Human Resources, Library, Firestone, F1 Snack bar, Frist Campus Center, G3 Athletic event ticket office, Jadwin Gym, I6 New South, E4 Limousine (to Newark Airport), Nassau Inn, Taxi, Nassau St., E1 Auditoriums: Betts, School of Architecture, Engineering and Applied Science, Palmer Square, E1 Teacher Preparation, Program in, G2; Dodds, Robertson Hall, G2; Helm, 50 School of, I1 Lost and found, Public Safety, 41 William St., H2 McCosh Hall, G2; Richardson, Alexander Exhibits: Art Museum, F2; Firestone Library, Stanhope Hall, E1 Telephones: Frist Campus Center, G3; Nassau Hall, E1; Taplin, Fine Hall, H4; Wood, 10 F1; Mudd Library, I2 Parking: visitor, garage, lot 7, E5 (campus Street, E1; Stanhope Hall, E1 McCosh Hall, G2 Fields Center for Equality and Cultural shuttle stop); parking information, Public Theatre: Intime, Murray-Dodge Hall, F2; Bookstore, Princeton University Store, D2 Understanding, 86 Olden St., I2 Safety,