Today's Challenges for Girls' Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excluded and Invisible

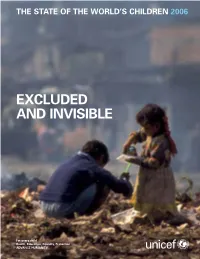

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 EXCLUDED AND INVISIBLE THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 © The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2005 The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Permission to reproduce any part of this publication The State of the World’s Children 2006 is required. Please contact the Editorial and Publications Section, Division of Communication, UNICEF, UNICEF House, 3 UN Plaza, UNICEF NY (3 UN Plaza, NY, NY 10017) USA, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: 212-326-7434 or 7286, Fax: 212-303-7985, E-mail: [email protected]. Permission E-mail: [email protected] will be freely granted to educational or non-profit Website: www.unicef.org organizations. Others will be requested to pay a small fee. Cover photo: © UNICEF/HQ94-1393/Shehzad Noorani ISBN-13: 978-92-806-3916-2 ISBN-10: 92-806-3916-1 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the advice and contributions of many inside and outside of UNICEF who provided helpful comments and made other contributions. Significant contributions were received from the following UNICEF field offices: Albania, Armenia, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Republic of Moldova, Serbia and Montenegro, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Venezuela and Viet Nam. Input was also received from Programme Division, Division of Policy and Planning and Division of Communication at Headquarters, UNICEF regional offices, the Innocenti Research Centre, the UK National Committee and the US Fund for UNICEF. -

Sierra Leone

SIERRA LEONE 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 1 (A) – January 2003 I was captured together with my husband, my three young children and other civilians as we were fleeing from the RUF when they entered Jaiweii. Two rebels asked to have sex with me but when I refused, they beat me with the butt of their guns. My legs were bruised and I lost my three front teeth. Then the two rebels raped me in front of my children and other civilians. Many other women were raped in public places. I also heard of a woman from Kalu village near Jaiweii being raped only one week after having given birth. The RUF stayed in Jaiweii village for four months and I was raped by three other wicked rebels throughout this A woman receives psychological and medical treatment in a clinic to assist rape period. victims in Freetown. In January 1999, she was gang-raped by seven revels in her village in northern Sierra Leone. After raping her, the rebels tied her down and placed burning charcoal on her body. (c) 1999 Corinne Dufka/Human Rights -Testimony to Human Rights Watch Watch “WE’LL KILL YOU IF YOU CRY” SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE SIERRA LEONE CONFLICT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] January 2003 Vol. -

Gender Gaps in Education

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12724 Gender Gaps in Education Graziella Bertocchi Monica Bozzano OCTOBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12724 Gender Gaps in Education Graziella Bertocchi University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, CEPR, CHILD, DGI, EIEF and IZA Monica Bozzano University of Pavia OCTOBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 12724 OCTOBER 2019 ABSTRACT Gender Gaps in Education* This chapter reviews the growing body of research in economics which concentrates on the education gender gap and its evolution, over time and across countries. -

Transnational Influences on Women's Arguments

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Undergraduate Honors Theses 2020-03-20 “Women Thus Educated”: Transnational Influences on omenW ’s Arguments for Female Education in Seventeenth-Century England Miranda Jessop Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Jessop, Miranda, "“Women Thus Educated”: Transnational Influences on omenW ’s Arguments for Female Education in Seventeenth-Century England" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 119. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht/119 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Honors Thesis “WOMEN THUS EDUCATED”: TRANSNATIONAL INFLUENCES ON WOMEN’S ARGUMENTS FOR FEMALE EDUCATION IN SEVENTEETH-CENTURY ENGLAND by Miranda Jessop Submitted to Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of graduation requirements for University Honors History Department Brigham Young University April 2020 Advisor: Rebecca de Schweinitz Honors Coordinator: Shawn Miller ii ABSTRACT “WOMEN THUS EDUCATED”: TRANSNATIONAL INFLUENCES ON WOMEN’S ARGUMENTS FOR FEMALE EDUCATION IN SEVENTEETH-CENTURY ENGLAND Miranda Jessop History Department Bachelor of Arts This thesis explores the intellectual history of proto-feminist thought in early modern England and seeks to better understand the transnational elements of and influences on proto- feminist theorists’ arguments in favor of women’s education in the late seventeenth century. A close reading of Bathsua Makin and Anna Maria Van Schurman’s essays in relation to one another, and within their social and historical context, reveals the importance of ideas of religion and social order, especially class, in understanding and justifying women’s education. -

Safeena Husain Founder and Executive Director Educate Girls

Safeena Husain Founder and Executive Director Educate Girls Safeena is the Founder and Executive Director of Educate Girls (EG), an NGO focused on mobilising communities for girls’ education. Under Safeena’s leadership, since EG’s inception in 2007, the NGO has enrolled 750,000+ girls in school and improved learning outcomes for 1.3 million+ children in India. Safeena’s guidance and leadership has been instrumental in EG achieving a major global milestone – the world’s first Development Impact Bond in education. On its completion, the bond surpassed both its target outcomes by achieving 160% of its learning target and 116% of its enrolment target. These results are testimony to the commitment of EG to deliver quality at scale (the organisation currently has 1,760 full time employees and 13,000+ community volunteers) and value to every single child in the program. She has also been instrumental in EG becoming the first Audacious project in Asia, a first-of-its-kind coalition that surfaces and funds critical projects with the potential to create global change. Previously, Safeena has worked extensively with rural and urban underserved communities in South America, Africa and Asia. She has been conferred with the 2017 NITI Aayog’s Women Transforming India Award, the 2016 NDTV-L’Oréal Paris Women of Worth Award, and has in the past received the British Asian Trust’s Special Recognition Award from HRH Prince Charles for outstanding contribution in education. Moreover, Educate Girls has received the prestigious 2015 Skoll Award, 2014 WISE Award, the 2014 USAID Millennium Alliance Award, the 2014 Stars Impact Award and the India Development Marketplace Award in 2011 from the World Bank. -

Millions of Civilians Have Been Killed in the Flames of War... But

VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 131 • 2003 “Millions of civilians have been killed in the flames of war... But there is hope too… in places like Sierra Leone, Angola and in the Horn of Africa.” —High Commissioner RUUD LUBBERS at a CrossroadsAfrica N°131 - 2003 Editor: Ray Wilkinson French editor: Mounira Skandrani Contributors: Millicent Mutuli, Astrid Van Genderen Stort, Delphine Marie, Peter Kessler, Panos Moumtzis Editorial assistant: UNHCR/M. CAVINATO/DP/BDI•2003 2 EDITORIAL Virginia Zekrya Africa is at another Africa slips deeper into misery as the world Photo department: crossroads. There is Suzy Hopper, plenty of good news as focuses on Iraq. Anne Kellner 12 hundreds of thousands of Design: persons returned to Sierra Vincent Winter Associés Leone, Angola, Burundi 4 AFRICAN IMAGES Production: (pictured) and the Horn of Françoise Jaccoud Africa. But wars continued in A pictorial on the African continent. Photo engraving: Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Aloha Scan - Geneva other areas, making it a very Distribution: mixed picture for the 12 COVER STORY John O’Connor, Frédéric Tissot continent. In an era of short wars and limited casualties, Maps: events in Africa are almost incomprehensible. UNHCR Mapping Unit By Ray Wilkinson Historical documents UNHCR archives Africa at a glance A brief look at the continent. Refugees is published by the Media Relations and Public Information Service of the United Nations High Map Commissioner for Refugees. The 17 opinions expressed by contributors Refugee and internally displaced are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do UNHCR/P. KESSLER/DP/IRQ•2003 populations. not imply the expression of any With the war in Iraq Military opinion or recognition on the part of officially over, UNHCR concerning the legal status UNHCR has turned its Refugee camps are centers for of a territory or of its authorities. -

77 the Incorporation of Girls in the Educational System In

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad de Alcalá POLIS. Revista de ideas y formas políticas de la Antigüedad Clásica 24, 2012, pp. 77-89. THE INCORPORATION OF GIRLS IN THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM IN HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN GREECE Konstantinos Mantas Athens1 From the Hellenistic era onwards, epigraphic evidence proves that some cities in Asia Minor, especially in Ionia and Aeolis, had continued Sappho’s educational tradition. In 2nd cent. BC, in the city of Teos, three ȖȡĮȝȝĮIJȠįȚįȐıțĮȜȠȚ, had been chosen to teach both paides and partenoi 2. At Smyrna and Pergamos, there was a magistrate who was responsible for the supervision of girls3. A very fragmented inscription from Pergamos recorded the curriculum of girls’ schooling: it included penmanship, music and reading as well as epic and elegiac poetry4. Tation, the daughter of Apollonios, is recorded as the winner in the contest for penmanship5. In the 2nd cent, BC, the city of Larissa in Thessaly, honoured a poetess from Smyrna, by granting her the rights of ʌȡȠȟİȞȓĮ, ȑȖțIJȘıȚȢ and ʌȡȠıIJĮıȓĮ6. The city of Tenos honoured Alcinoe from Aetolia, who, according to the restoration of the inscription, had 1 This article is based on a paper which was presented under the title«From Sappho to St Macrina and Hypatia: The changing patterns of women’s education in postclassical antiquity» at the 4th International Conference of SSCIP, 18th of September, 2010. 2 Syll. 3 no 578, ll.9-10. 3 CIG no 3185. 4 Ath. Mitt 37, (1912), no 16. 5 At. Mit. -

UNICEF Photo of the Year – Previous Award Winners

UNICEF Photo of the Year – Previous Award Winners 2014 First Prize Insa Hagemann / Stefan Finger, Germany, laif Their reportage on the effects of sextourism in the Philippines gives an insight in the situation of children whose fathers live abroad. Second Prize Christian Werner, Germany, laif For his reportage on internally displaced people from Shinghai district, Iraq Third Prize Brent Stirton, South Africa, Getty Images for his reportage “Before and after eye surgery” on children with congenital cataract blindness in India. 2013 Winner Niclas Hammarström, Sweden, Kontinent His photo reportage captures the life of the children in Aleppo caught between the frontlines. 2012 First Prize Alessio Romenzi, Italien, Agentur Corbis Images The winning picture shows a girl waiting for medical examination at a hospital in Aleppo, Syria. The camera captures the fear in her eyes as she looks at a man holding a Kalashnikov. Second Prize Abhijit Nandi, India, Freelance Photographer In a long-term photo project, the photographer documents the many different forms of child labor in his home country. Third Prize Andrea Gjestvang, Norwegen, Agentur Moment The third prize was awarded to Norwegian photographer Andrea Gjestvang for her work with the victims of the shooting on Utøya Island. Forth Prize Laerke Posselt, Dänemark, Agentur Moment for her look behind the scenes of beauty pageants for toddlers in the USA. 1 2011 First Prize Kai Löffelbein, Germany, Student, University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Hannover for his photo of a boy at the infamous toxic waste dump Agbogbloshie, near Ghana’s capital Accra. Surrounded by highly toxic fumes and electronic waste from Western countries, the boy is lifting the remnants of a monitor above his head. -

Essays on Spatial Development by Alexander David Rothenberg a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements

Essays on Spatial Development by Alexander David Rothenberg A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Bryan S. Graham, Chair Professor Edward Miguel Professor Patrick Kline Professor Robert Helsley Spring 2012 Essays on Spatial Development Copyright 2012 by Alexander David Rothenberg Abstract Essays on Spatial Development by Alexander David Rothenberg Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Bryan S. Graham, Chair This dissertation contains three essays on the relationship between the spatial distribution of economic activity and di↵erent types of public goods. In the first essay, I study how changes in transport infrastructure a↵ect the location decisions of firms by examining how manufacturers responded to changes in road quality in Indonesia. Using new data, I docu- ment massive upgrades to Indonesia’s highway networks during the 1990s, a period in which national transportation funding increased by 83 percent. I first show that these road im- provements were accompanied by a significant dispersion of manufacturing activity, and that di↵erent industries responded in ways predicted by theory. To make better counterfactual predictions, I develop a structural model of location choice in which firms face a trade o↵: locating closer to demand sources requires firms to pay higher factor prices. The model predicts that some location characteristics relevant to firms are determined in equilibrium, necessitating the use of instrumental variables. I estimate a random coefficients logit model with endogenous choice characteristics and find significant di↵erences in firms’ willingness to pay for greater market access across di↵erent industrial sectors. -

Mother-Women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 “Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott Kelly Ann Masterson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Masterson, Kelly Ann, "“Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1647 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Kelly Ann Masterson entitled "“Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Katherine L. Chiles, William J. Hardwig Accepted -

NEW LESSONS: the Power of Educating Adolescent Girls CONTENTS

NEW LESSONS THE POWER OF EDUCATING ADOLESCENT GIRLS A GIRLS COUNT REPORT ON ADOLESCENT GIRLS CYNTHIA B. LLOYD POPULATION COUNCIL NEW LESSONS THE POWER OF EDUCATING ADOLESCENT GIRLS Cover Photo Girls at a rural secondary school in Bangladesh head home after class. Offering new options and access to secondary school is a major prior- ity for adolescent girls’ education. Photo Credit: Brent Stirton / Getty Images NEW LESSONS THE POWER OF EDUCATING ADOLESCENT GIRLS Cover Photo Girls at a rural secondary school in Bangladesh head home after class. Offering new options and access to secondary school is a major prior- ity for adolescent girls’ education. Photo Credit: Brent Stirton / Getty Images TAkING action FOR ADOLESCENT GIRLS’ education or family obligations. The programs can also provide COUNT INVEST supplementary training beyond the formal curricu- ADVOCATE lum for the development of skills for social and civic Collect and compile data on Expand opportunities for girls participation—in the process teaching basic health, Promote easy transitions non-formal education to attend secondary school reproductive health, and financial literacy. between non-formal and A questionnaire module on non-formal education Governments should define basic education as formal schools should be introduced into national household surveys education through lower secondary school, or to age Produce curricula relevant to Complementary schools should be developed within and censuses to collect data on the extent and cover- 16. To accommodate the resulting influx of students, adolescent girls the non-formal education system to help girls, many age of non-formal schooling, and its implementation governments and the private sector should increase Adolescent girls in the developing world need to of them primary-school dropouts, continue on should be tested on a pilot basis in several countries. -

Sexism in Schools

SEXISM AND PUBLIC EDUCATION By Ellen Knight1 Looking back over the years of public education in Winchester since 1850, one might expect to see gradual progression towards equity in the opportunities, attitude, and treatment for girls and women. Actually, one encounters a more complex history of education and women in Winchester. For example, in its report for the school year 1850-51, the School Committee (J. M. Steele, Charles Goddard, and F. O. Prince) stated that “the object of the high school is threefold. 1st. to give young men a thorough business education. 2nd. To prepare young men for college. 3d. To give young ladies that exact knowledge, that A late-19th-century group of students with their complete mental culture which will fit teacher at the Mystic School them to become teachers, and to fill and adorn any station into which they are liable to be called.” While certainly exhibiting differing attitudes toward education for boys and girls, the School Committee nevertheless exhibited great concern for girls’ education, devoting four pages of its report to the subject. But in 1863, another school committee, composed of five men, set forth the advantages and necessity of a high school by quoting from the 1851 report the first two objects only. To be sure, much of the 1851 report on girls’ education is a disparagement of female seminaries, with which the later committee may have disagreed. However, the appearance of the 1863 report is that high school existed only for boys. The 1851 committee was quite favorable to female education, though they saw different goals for educated girls than for boys.