The Role of Phylogenetics in Comparative Genetics1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes: the Mathematics of Phylogenetics

Lecture Notes: The Mathematics of Phylogenetics Elizabeth S. Allman, John A. Rhodes IAS/Park City Mathematics Institute June-July, 2005 University of Alaska Fairbanks Spring 2009, 2012, 2016 c 2005, Elizabeth S. Allman and John A. Rhodes ii Contents 1 Sequences and Molecular Evolution 3 1.1 DNA structure . .4 1.2 Mutations . .5 1.3 Aligned Orthologous Sequences . .7 2 Combinatorics of Trees I 9 2.1 Graphs and Trees . .9 2.2 Counting Binary Trees . 14 2.3 Metric Trees . 15 2.4 Ultrametric Trees and Molecular Clocks . 17 2.5 Rooting Trees with Outgroups . 18 2.6 Newick Notation . 19 2.7 Exercises . 20 3 Parsimony 25 3.1 The Parsimony Criterion . 25 3.2 The Fitch-Hartigan Algorithm . 28 3.3 Informative Characters . 33 3.4 Complexity . 35 3.5 Weighted Parsimony . 36 3.6 Recovering Minimal Extensions . 38 3.7 Further Issues . 39 3.8 Exercises . 40 4 Combinatorics of Trees II 45 4.1 Splits and Clades . 45 4.2 Refinements and Consensus Trees . 49 4.3 Quartets . 52 4.4 Supertrees . 53 4.5 Final Comments . 54 4.6 Exercises . 55 iii iv CONTENTS 5 Distance Methods 57 5.1 Dissimilarity Measures . 57 5.2 An Algorithmic Construction: UPGMA . 60 5.3 Unequal Branch Lengths . 62 5.4 The Four-point Condition . 66 5.5 The Neighbor Joining Algorithm . 70 5.6 Additional Comments . 72 5.7 Exercises . 73 6 Probabilistic Models of DNA Mutation 81 6.1 A first example . 81 6.2 Markov Models on Trees . 87 6.3 Jukes-Cantor and Kimura Models . -

In Defence of the Three-Domains of Life Paradigm P.T.S

van der Gulik et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:218 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-1059-z REVIEW Open Access In defence of the three-domains of life paradigm P.T.S. van der Gulik1*, W.D. Hoff2 and D. Speijer3* Abstract Background: Recently, important discoveries regarding the archaeon that functioned as the “host” in the merger with a bacterium that led to the eukaryotes, its “complex” nature, and its phylogenetic relationship to eukaryotes, have been reported. Based on these new insights proposals have been put forward to get rid of the three-domain Model of life, and replace it with a two-domain model. Results: We present arguments (both regarding timing, complexity, and chemical nature of specific evolutionary processes, as well as regarding genetic structure) to resist such proposals. The three-domain Model represents an accurate description of the differences at the most fundamental level of living organisms, as the eukaryotic lineage that arose from this unique merging event is distinct from both Archaea and Bacteria in a myriad of crucial ways. Conclusions: We maintain that “a natural system of organisms”, as proposed when the three-domain Model of life was introduced, should not be revised when considering the recent discoveries, however exciting they may be. Keywords: Eucarya, LECA, Phylogenetics, Eukaryogenesis, Three-domain model Background (English: domain) as a higher taxonomic level than The discovery that methanogenic microbes differ funda- regnum: introducing the three domains of cellular life, Ar- mentally from Bacteria such as Escherichia coli or Bacillus chaea, Bacteria and Eucarya. This paradigm was proposed subtilis constitutes one of the most important biological by Woese, Kandler and Wheelis in PNAS in 1990 [2]. -

Phylogenetics Topic 2: Phylogenetic and Genealogical Homology

Phylogenetics Topic 2: Phylogenetic and genealogical homology Phylogenies distinguish homology from similarity Previously, we examined how rooted phylogenies provide a framework for distinguishing similarity due to common ancestry (HOMOLOGY) from non-phylogenetic similarity (ANALOGY). Here we extend the concept of phylogenetic homology by making a further distinction between a HOMOLOGOUS CHARACTER and a HOMOLOGOUS CHARACTER STATE. This distinction is important to molecular evolution, as we often deal with data comprised of homologous characters with non-homologous character states. The figure below shows three hypothetical protein-coding nucleotide sequences (for simplicity, only three codons long) that are related to each other according to a phylogenetic tree. In the figure the nucleotide sequences are aligned to each other; in so doing we are making the implicit assumption that the characters aligned vertically are homologous characters. In the specific case of nucleotide and amino acid alignments this assumption is called POSITIONAL HOMOLOGY. Under positional homology it is implicit that a given position, say the first position in the gene sequence, was the same in the gene sequence of the common ancestor. In the figure below it is clear that some positions do not have identical character states (see red characters in figure below). In such a case the involved position is considered to be a homologous character, while the state of that character will be non-homologous where there are differences. Phylogenetic perspective on homologous characters and homologous character states ACG TAC TAA SYNAPOMORPHY: a shared derived character state in C two or more lineages. ACG TAT TAA These must be homologous in state. -

Phylogenetics of Buchnera Aphidicola Munson Et Al., 1991

Türk. entomol. derg., 2019, 43 (2): 227-237 ISSN 1010-6960 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16970/entoted.527118 E-ISSN 2536-491X Original article (Orijinal araştırma) Phylogenetics of Buchnera aphidicola Munson et al., 1991 (Enterobacteriales: Enterobacteriaceae) based on 16S rRNA amplified from seven aphid species1 Farklı yaprak biti türlerinden izole edilen Buchnera aphidicola Munson et al., 1991 (Enterobacteriales: Enterobacteriaceae)’nın 16S rRNA’ya göre filogenetiği Gül SATAR2* Abstract The obligate symbiont, Buchnera aphidicola Munson et al., 1991 (Enterobacteriales: Enterobacteriaceae) is important for the physiological processes of aphids. Buchnera aphidicola genes detected in seven aphid species, collected in 2017 from different plants and altitudes in Adana Province, Turkey were analyzed to reveal phylogenetic interactions between Buchnera and aphids. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced for this purpose and a phylogenetic tree built up by the neighbor-joining method. A significant correlation between B. aphidicola genes and the aphid species was revealed by this phylogenetic tree and the haplotype network. Specimens collected in Feke from Solanum melongena L. was distinguished from the other B. aphidicola genes on Aphis gossypii Glover, 1877 (Hemiptera: Aphididae) with a high bootstrap value of 99. Buchnera aphidicola in Myzus spp. was differentiated from others, and the difference between Myzus cerasi (Fabricius, 1775) and Myzus persicae (Sulzer, 1776) was clear. Although, B. aphidicola is specific to its host aphid, certain nucleotide differences obtained within the species could enable specification to geographic region or host plant in the future. Keywords: Aphid, genetic similarity, phylogenetics, symbiotic bacterium Öz Obligat simbiyont, Buchnera aphidicola Munson et al., 1991 (Enterobacteriales: Enterobacteriaceae), yaprak bitlerinin fizyolojik olaylarının sürdürülmesinde önemli bir rol oynar. -

Introductory Activities

TEACHER’S GUIDE Introduction Dean Madden Introductory NCBE, University of Reading activities Version 1.0 CaseCase Studies introduction Introductory activities The activities in this section explain the basic principles behind the construction of phylogenetic trees, DNA structure and sequence alignment. Students are also intoduced to the Geneious software. Before carrying out the activities in the DNA to Darwin Case studies, students will need to understand: • the basic principles behind the construction of an evolutionary tree or phylogeny; • the basic structure of DNA and proteins; • the reasons for and the principle of alignment; • use of some features of the Geneious computer software (basic version). The activities in this introduction are designed to achieve this. Some of them will reinforce what students may already know; others involve new concepts. The material includes extension activities for more able students. Evolutionary trees In 1837, 12 years before the publication of On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin famously drew an evolutionary tree in one of his notebooks. The Origin also included a diagram of an evolutionary tree — the only illustration in the book. Two years before, Darwin had written to his friend Thomas Henry Huxley, saying: ‘The time will come, I believe, though I shall not live to see it, when we shall have fairly true genealogical trees of each great kingdom of Nature.’ Today, scientists are trying to produce the ‘Tree of Life’ Darwin foresaw, using protein, DNA and RNA sequence data. Evolutionary trees are covered on pages 2–7 of the Student’s guide and in the PowerPoint and Keynote slide presentations. -

1 "Principles of Phylogenetics: Ecology

"PRINCIPLES OF PHYLOGENETICS: ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION" Integrative Biology 200 Spring 2016 University of California, Berkeley D.D. Ackerly March 7, 2016. Phylogenetics and Adaptation What is to be explained? • What is the evolutionary history of trait x that we see in a lineage (homology) or multiple lineages (homoplasy) - adaptations as states • Is natural selection the primary evolutionary process leading to the ‘fit’ of organisms to their environment? • Why are some traits more prevalent (occur in more species): number of origins vs. trait- dependent diversification rates (speciation – extinction) Some high points in the history of the adaptation debate: 1950s • Modern Synthesis of Genetics (Dobzhansky), Paleontology (Simpson) and Systematics (Mayr, Grant) 1960s • Rise of evolutionary ecology – synthesis of ecology with strong adaptationism via optimality theory, with little to no history; leads to Sociobiology in the 70s • Appearance of cladistics (Hennig) 1972 • Eldredge and Gould – punctuated equilibrium – argue that Modern Synthesis can’t explain pervasive observation of stasis in fossil record; Gould focuses on development and constraint as explanations, Eldredge more on ecology and importance of migration to minimize selective pressure 1979 • Gould and Lewontin – Spandrels – general critique of adaptationist program and call for rigorous hypothesis testing of alternatives for the ‘fit’ between organism and environment 1980’s • Debate on whether macroevolution can be explained by microevolutionary processes • Comparative methods -

The Caper Package: Comparative Analysis of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R

The caper package: comparative analysis of phylogenetics and evolution in R David Orme April 16, 2018 This vignette documents the use of the caper package for R (R Development Core Team, 2011) in carrying out a range of comparative analysis methods for phylogenetic data. The caper package, and the code in this vignette, requires the ape package (Paradis et al., 2004) along with the packages mvtnorm and MASS. Contents 1 Background 2 2 Comparative datasets 3 2.1 The comparative.data class and objects. .3 2.1.1 na.omit ......................................3 2.1.2 subset ......................................5 2.1.3 [ ..........................................5 2.2 Example datasets . .6 3 Methods and functions provided by caper. 7 3.0.1 Phylogenetic linear models . .7 3.0.2 Fitting phylogenetic GLS models: pgls ....................8 3.1 Optimising branch length transformations: profile.pgls...............9 3.1.1 Criticism and simplification ofpgls models: plot, anova and AIC...... 11 3.2 Phylogenetic independent contrasts . 12 3.2.1 Variable names in contrast functions . 12 3.2.2 Continuous variables: crunch .......................... 13 3.2.3 Categorical variables: brunch .......................... 13 3.2.4 Species richness contrasts: macrocaic ..................... 14 3.2.5 Phylogenetic signal: phylo.d .......................... 15 3.3 Checking and comparing contrast models. 16 3.3.1 Testing evolutionary assumptions: caic.diagnostics............. 16 3.3.2 Robust contrasts: caic.robust ......................... 17 3.3.3 Model criticism: plot .............................. 19 3.3.4 Model comparison: anova & AIC ........................ 20 3.4 Other comparative functions . 21 3.4.1 Tree imbalance: fusco.test .......................... 21 3.5 Phylogenetic diversity: pd.calc, pd.bootstrap and ed.calc............ -

Full of Beans: a Study on the Alignment of Two Flowering Plants Classification Systems

Full of beans: a study on the alignment of two flowering plants classification systems Yi-Yun Cheng and Bertram Ludäscher School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA {yiyunyc2,ludaesch}@illinois.edu Abstract. Advancements in technologies such as DNA analysis have given rise to new ways in organizing organisms in biodiversity classification systems. In this paper, we examine the feasibility of aligning two classification systems for flowering plants using a logic-based, Region Connection Calculus (RCC-5) ap- proach. The older “Cronquist system” (1981) classifies plants using their mor- phological features, while the more recent Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV (APG IV) (2016) system classifies based on many new methods including ge- nome-level analysis. In our approach, we align pairwise concepts X and Y from two taxonomies using five basic set relations: congruence (X=Y), inclusion (X>Y), inverse inclusion (X<Y), overlap (X><Y), and disjointness (X!Y). With some of the RCC-5 relationships among the Fabaceae family (beans family) and the Sapindaceae family (maple family) uncertain, we anticipate that the merging of the two classification systems will lead to numerous merged solutions, so- called possible worlds. Our research demonstrates how logic-based alignment with ambiguities can lead to multiple merged solutions, which would not have been feasible when aligning taxonomies, classifications, or other knowledge or- ganization systems (KOS) manually. We believe that this work can introduce a novel approach for aligning KOS, where merged possible worlds can serve as a minimum viable product for engaging domain experts in the loop. Keywords: taxonomy alignment, KOS alignment, interoperability 1 Introduction With the advent of large-scale technologies and datasets, it has become increasingly difficult to organize information using a stable unitary classification scheme over time. -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (2002) Plant Systematics: a Phylogenetic Approach. Chapter 7. an Overview of Green

UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS An Overview of Green Plant Phylogeny he word plant is commonly used to refer to any auto- trophic eukaryotic organism capable of converting light energy into chemical energy via the process of photosynthe- sis. More specifically, these organisms produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water in the presence of chlorophyll inside of organelles called chloroplasts. Sometimes the term plant is extended to include autotrophic prokaryotic forms, especially the (eu)bacterial lineage known as the cyanobacteria (or blue- green algae). Many traditional botany textbooks even include the fungi, which differ dramatically in being heterotrophic eukaryotic organisms that enzymatically break down living or dead organic material and then absorb the simpler products. Fungi appear to be more closely related to animals, another lineage of heterotrophs characterized by eating other organisms and digesting them inter- nally. In this chapter we first briefly discuss the origin and evolution of several separately evolved plant lineages, both to acquaint you with these important branches of the tree of life and to help put the green plant lineage in broad phylogenetic perspective. We then focus attention on the evolution of green plants, emphasizing sev- eral critical transitions. Specifically, we concentrate on the origins of land plants (embryophytes), of vascular plants (tracheophytes), of 1 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2 CHAPTER SEVEN seed plants (spermatophytes), and of flowering plants dons.” In some cases it is possible to abandon such (angiosperms). names entirely, but in others it is tempting to retain Although knowledge of fossil plants is critical to a them, either as common names for certain forms of orga- deep understanding of each of these shifts and some key nization (e.g., the “bryophytic” life cycle), or to refer to a fossils are mentioned, much of our discussion focuses on clade (e.g., applying “gymnosperms” to a hypothesized extant groups. -

Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation

i1 Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation William A. DiMichele, William E. Stein, and Richard M. Bateman DiMichele, W.A., Stein, W.E., and Bateman, R.M. 2001. Ecological sorting of vascular plant classes during the Paleozoic evolutionary radiation. In: W.D. Allmon and D.J. Bottjer, eds. Evolutionary Paleoecology: The Ecological Context of Macroevolutionary Change. Columbia University Press, New York. pp. 285-335 THE DISTINCTIVE BODY PLANS of vascular plants (lycopsids, ferns, sphenopsids, seed plants), corresponding roughly to traditional Linnean classes, originated in a radiation that began in the late Middle Devonian and ended in the Early Carboniferous. This relatively brief radiation followed a long period in the Silurian and Early Devonian during wrhich morphological complexity accrued slowly and preceded evolutionary diversifications con- fined within major body-plan themes during the Carboniferous. During the Middle Devonian-Early Carboniferous morphological radiation, the major class-level clades also became differentiated ecologically: Lycopsids were cen- tered in wetlands, seed plants in terra firma environments, sphenopsids in aggradational habitats, and ferns in disturbed environments. The strong con- gruence of phylogenetic pattern, morphological differentiation, and clade- level ecological distributions characterizes plant ecological and evolutionary dynamics throughout much of the late Paleozoic. In this study, we explore the phylogenetic relationships and realized ecomorphospace of reconstructed whole plants (or composite whole plants), representing each of the major body-plan clades, and examine the degree of overlap of these patterns with each other and with patterns of environmental distribution. We conclude that 285 286 EVOLUTIONARY PALEOECOLOGY ecological incumbency was a major factor circumscribing and channeling the course of early diversification events: events that profoundly affected the structure and composition of modern plant communities. -

Fundamentals of Palaeobotany Fundamentals of Palaeobotany

Fundamentals of Palaeobotany Fundamentals of Palaeobotany cuGU .叮 v FimditLU'φL-EjAA ρummmm 吋 eαymGfr 伊拉ddd仇側向iep M d、 況 O C O W Illustrations by the author uc削 ∞叩N Nn凹創 刊,叫MH h 咀 可 白 a aEE-- EEA First published in 1987 by Chapman αndHallLtd 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Published in the USA by Chα~pman and H all 29 West 35th Street: New Yo地 NY 10001 。 1987 S. V. M秒len Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1987 ISBN-13: 978-94-010-7916-7 e-ISBN-13: 978-94-009-3151-0 DO1: 10.1007/978-94-009-3151-0 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted, or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Mey凹, Sergei V. Fundamentals of palaeobotany. 1. Palaeobotany I. Title 11. Osnovy paleobotaniki. English 561 QE905 Library 01 Congress Catα loging in Publication Data Mey凹, Sergei Viktorovich. Fundamentals of palaeobotany. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Paleobotany. I. Title. QE904.AIM45 561 8ι13000 Contents Foreword page xi Introduction xvii Acknowledgements xx Abbreviations xxi 1. Preservation 抄'pes αnd techniques of study of fossil plants 1 2. Principles of typology and of nomenclature of fossil plants 5 Parataxa and eutaxa S Taxa and characters 8 Peculiarity of the taxonomy and nomenclature of fossil plants 11 The binary (dual) system of fossil plants 12 The reasons for the inflation of generic na,mes 13 The species problem in palaeobotany lS The polytypic concept of the species 17 Assemblage-genera and assemblage-species 17 The cladistic methods 18 3. -

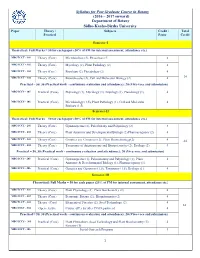

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 Onward)

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 onward) Department of Botany Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University Paper Theory / Subjects Credit / Total Practical Paper Credit Semester-I Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 101 Theory (Core) Microbiology (2), Phycology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 102 Theory (Core) Mycology (2), Plant Pathology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 103 Theory (Core) Bryology (2), Pteridology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 104 Theory (Core) Biomolecules (2), Cell and Molecular Biology (2) 4 24 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 105 Practical (Core) Phycology (1), Mycology (1), Bryology (1), Pteridology (1). 4 MBOTCCS - 106 Practical (Core) Microbiology (1.5), Plant Pathology (1), Cell and Molecular 4 Biology (1.5). Semester-II Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 201 Theory (Core) Gymnosperms (2), Paleobotany and Palynology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 202 Theory (Core) Plant Anatomy and Developmental Biology (2) Pharmacognosy (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 203 Theory (Core) Genetics and Genomics (2), Plant Biotechnology(2) 4 24 MBOTCCT - 204 Theory (Core) Taxonomy of Angiosperms and Biosystematics (2), Ecology (2) 4 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 205 Practical (Core) Gymnosperms (1), Palaeobotany and Palynology (1), Plant 4 Anatomy & Developmental Biology (1), Pharmacognosy (1). MBOTCCS - 206 Practical (Core) Genetics and Genomics (1.5), Taxonomy (1.5), Ecology (1). 4 Semester-III Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 301 Theory (Core) Plant Physiology (2), Plant Biochemistry (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 302 Theory (Core) Economic Botany (2), Bioinformatics (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 303 Theory (Core) Elements of Forestry (2), Seed Technology (2).