Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

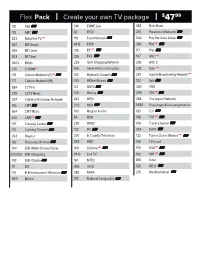

Flex Pack Create Your Own TV Package

Flex Pack C reate your own TV package $4799 118 A&E 134 EVINE Live 368 Nick Music 131 AMC 82 FETV 241 Paramount Network 823 BabyFirst TV SAP 110 Food Network 500 Pay-Per-View Guide 362 BET Gospel 9415 FSTV 388 PixL SAP 365 BET Jams 136 FX SAP 117 Pop 363 BET Soul 125 FXX 137 QVC SAP 9403 BYUtv 229 Gem Shopping Network 255 QVC 2 210 C-SPAN SAP 165 Great American Country 225 Sale SAP 176 Cartoon Network (E) SAP 185 Hallmark Channel 257 SonLife Broadcasting Network SAP 177 Cartoon Network (W) 130 HDNet Movies 122 Syfy 884 CCTV-E 112 HGTV 260 TBN 279 CCTV News 120 History 209 TBS SAP 267 Christian Television Network 843 HITN 268 The Impact Network 166 CMT 202 HLN 9393 Three Angels Broadcasting Network 364 CMT Music 103 Hopper Insider 183 TLC 200 CNN SAP 84 HSN 138 TNT SAP 107 Comedy Central 226 HSN2 196 Travel Channel 113 Cooking Channel 133 IFC 242 truTV 263 Daystar 230 In Country Television 132 Turner Classic Movies SAP 182 Discovery Channel 259 INSP 106 TV Land 100 DISH Multi-Channel View 108 Lifetime SAP 105 USA SAP 123/220/221 DISH Shopping 9410 Link TV 162 VH1 SAP 102 DISH Studio 161 MTV2 846 V-me 111 DIY 366 mtvU 128 WE tv 114 E! Entertainment Television 286 NASA 215 WeatherNation 9411 Enlace 197 National Geographic + 50 Starter Then add the Channel Packs you want like Locals, News, and Outdoor Channels Local Channels* $12/mo. Heartland Pack $6/mo. -

Insecticide OAN Network

24 www.sdbj.com MAY 4, 2020 Insecticide from page 6 third the cost of bio-pesticides.” The sustainable factor is likely also to be a selling point for Agragene. Climate change“ and the way ag is done today is not a sustainable future. GORDON ALTON “Climate change and the way ag is done today is not a sustainable future,” Alton said. “Spraying chemicals all the time leads to chemical resistance.” Alton said that climate change has led to more bugs showing up earlier. They live longer; they are more active. Agragene is work- ing on an eco-friendly solution. Photo courtesy of One America News Network Drone Delivery Liz Wheeler is the host of “Tipping Point with Liz Wheeler” seen nightly on One America News Network. Agragene plans to use drones to de- AT&T TV—a new video product available As a National News Network, How Do liver its sterile insects. for every home nationwide—DirecTV, You Think OAN and Its Mission Will According to Alton, drones can cover OAN Network and AT&T U-Verse. In addition, OAN is Have Changed When the COVID-19 an acre in one to two minutes. They are from page 1 available on streaming products such as Crisis is Over? currently being used in a couple states. KlowdTV.com, Roku, Amazon Fire TV, COVID-19 has reinforced our mission The company says it would partner with They first Herring and Apple TV. to keep our viewers informed with the a drone service rather than operate its launched sister Networks, Inc. latest and most accurate news possible. -

The 2020 Election 2 Contents

Covering the Coverage The 2020 Election 2 Contents 4 Foreword 29 Us versus him Kyle Pope Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 5 Why did Matt Drudge turn on August 10, 2020 Donald Trump? Bob Norman 37 The campaign begins (again) January 29, 2020 Kyle Pope August 12, 2020 8 One America News was desperate for Trump’s approval. 39 When the pundits paused Here’s how it got it. Simon van Zuylen–Wood Andrew McCormick Summer 2020 May 27, 2020 47 Tuned out 13 The story has gotten away from Adam Piore us Summer 2020 Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 57 ‘This is a moment for June 3, 2020 imagination’ Mychal Denzel Smith, Josie Duffy 22 For Facebook, a boycott and a Rice, and Alex Vitale long, drawn-out reckoning Summer 2020 Emily Bell July 9, 2020 61 How to deal with friends who have become obsessed with 24 As election looms, a network conspiracy theories of mysterious ‘pink slime’ local Mathew Ingram news outlets nearly triples in size August 25, 2020 Priyanjana Bengani August 4, 2020 64 The only question in news is ‘Will it rate?’ Ariana Pekary September 2, 2020 3 66 Last night was the logical end 92 The Doociness of America point of debates in America Mark Oppenheimer Jon Allsop October 29, 2020 September 30, 2020 98 How careful local reporting 68 How the media has abetted the undermined Trump’s claims of Republican assault on mail-in voter fraud voting Ian W. Karbal Yochai Benkler November 3, 2020 October 2, 2020 101 Retire the election needles 75 Catching on to Q Gabriel Snyder Sam Thielman November 4, 2020 October 9, 2020 102 What the polls show, and the 78 We won’t know what will happen press missed, again on November 3 until November 3 Kyle Pope Kyle Paoletta November 4, 2020 October 15, 2020 104 How conservative media 80 E. -

E02630506 Fiber Creative Templates Q2 2021 Spring Channel

Channel Listings for Atlanta All channels available in HD unless otherwise noted. Download the latest version at SD Channel available in SD only google.com/fiber/channels ES Spanish language channel As of Summer 2021, channels and channel listings are subject to change. Local A—C ESPN Deportes ES 215 National Geographic 327 ESPNews 211 Channel C-Span 131 A&E 298 ESPNU 213 NBC Sports Network 203 ES C-Span 2 132 ACC Network 221 EWTN 456 NBC Universo 487 C-Span 3 133 AMC 288 EWTN en Espanol ES 497 NewsNation 303 Clayton County 144 American Heroes 340 NFL Network 219 SD Food Network 392 Access TV Channel SD FOX Business News 120 Nick2 422 COBB TV 140 Animal Planet 333 ES Nickelodeon 421 FOX Deportes 470 Fulton County Schools 145 Bally Sports South 204 Nick Jr. 425 SD FOX News Channel 119 TV (FCSTV) Bally Sports Southeast 205 SD FOX Sports 1 208 Nick Music 362 Fulton Government TV 141 BBC America 287 FOX Sports 2 209 Nicktoons 423 HSN 23 BBC World News 112 Freeform 286 HSN2 24 BET 355 O—T Fusion 105 NASA 321 BET Gospel SD 378 FX 282 QVC 25 BET Her SD 356 Olympic Channel 602 FX Movie Channel 281 QVC2 26 BET Jams SD 363 OWN: Oprah Winfrey 334 FXX 283 TV24 143 BET Soul SD 369 Oxygen 404 WAGADT (FOX) 5 FYI 299 Boomerang 431 Paramount Network 341 SD WAGADT2 (Movies!) 72 GAC: Great American 373 SD Bravo 296 Country POSITIV TV 453 WAGADT3 (Buzzr) SD 73 BTN2 623 Galavisión ES 467 Science Channel 331 WATCDT SD 2 BTN3 624 Golf Channel 249 SEC Network 216 WATCDT2 (WATC TOO) SD 83 BTN4 625 Hallmark Channel 291 SEC Overflow 617 WATLDT (MyNetworkTV) 36 SD -

Exhibit 2 – Channel Lineup

Exhibit 2 BASIC PACKAGE STANDARD PACKAGE Channel/Network SD HD Channel/Network SD HD Channel/Network SD HD Channel/Network SD HD Includes the following: Includes Basic plus the following: E! 282 682 Paramount Network 253 653 Sportsman Channel 162 562 MC Easy Listening 812 ESPN 100 500 Science Channel 267 667 TBS 255 655 MC Gospel 813 Channel/Network SD HD Channel/Network SD HD ESPN Classic 103 SEC Network 142 542 Tennis Channel 131 531 MC Hip Hop & R&B 814 ABC (WTEN) 2 402 Discovery Channel 200 600 ESPN2 101 501 Sports New York 113 513 Travel Channel 207 607 MC Hip Hop Classics 815 Hallmark Channel 192 592 Food Network 273 673 Turner Classic Movies 845 MC Hit List 816 Bounce (WXXA) 50 Syfy Channel 300 700 Hallmark Movies & Mysteries 328 728 FOX Business News 63 463 Teen Nick 227 627 Universal Kids 228 628 MC Indie 817 BYU TV 180 580 INSP 298 698 FOX News Channel 62 462 TNT 252 652 Viceland 301 701 MC Jazz 818 CBS (WRGB) 3 403 Investigation Discovery 264 664 FOX Sports 1 104 504 Toku 235 635 YouToo America 302 MC Kidz Only 819 MC Light Classical 820 Charge (WCWN) 46 Outdoor Channel 160 560 FOX Sports 2 105 505 USA Network 190 590 RFD TV 208 Freeform 232 632 MC Love Songs 821 Comet (WRGB) 44 VH1 315 715 TLC 268 668 FX 250 650 TRUE HD CHANNELS*** MC Max 822 CSPAN 80 480 YES 116 516 Tru TV 303 FXX 251 651 Add to any package: MC Metal 823 CSPAN 2 81 481 TV Land 191 Golf Channel 130 530 MC Mexicana 824 CW (WCWN) 21 421 WE TV 287 687 GSN 297 697 EXPANDED PACKAGE MC Musica Urbana 825 Weather Channel 70 470 Headline News 65 465 Channel/Network -

The Future of 'Stop the Steal' Post-Election Trajectories for Right-Wing Mobilization in the Us

DECEMBER 2020 THE FUTURE OF 'STOP THE STEAL' POST-ELECTION TRAJECTORIES FOR RIGHT-WING MOBILIZATION IN THE US About the US Crisis Monitor The US Crisis Monitor supports data-driven initiatives to build community resilience and facilitate efforts to track, prevent, and mitigate political violence in America. A joint project of the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) and the Bridging Divides Initiative (BDI) at Princeton University, the US Crisis Monitor provides the public with real-time data and analysis on political violence and demonstrations around the country, establishing an evidence base from which to identify risks, hotspots, and available resources to empower local communities in times of crisis. Contents Introduction 4 Shifting Trends: Pre- and Post-Election 7 Dominant Protest Movements 7 Armed Group Activity 11 Potential Trajectories 15 (1) Demonstrations limited largely to militia groups 15 (2) Mass mobilization of decentralized, armed individuals 18 (3) Increasing attacks by violent sole perpetrators 19 (4) Unarmed mass mobilization 21 Conclusion 23 2 Authors Dr. Roudabeh Kishi is the Director of Research & Innovation at ACLED. She oversees the quality, production, and coverage of all ACLED data across the globe; leads research and analysis across regional teams; aids in new partnerships with local sources and users; and supports the capacity building of NGOs and conflict observatories around the world. Dr. Kishi holds a Ph.D. in Government and Politics from the University of Maryland with specializations in international relations and quantitative methodology. Hampton Stall is a Senior Researcher at ACLED and a conflict anthropologist with a Masters in Development Practice from Emory University. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA US DOMINION, INC., DOMINION VOTING SYSTEMS, INC., and DOMINION

Case 1:21-cv-02130-CJN Document 1 Filed 08/10/21 Page 1 of 213 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) US DOMINION, INC., DOMINION ) VOTING SYSTEMS, INC., and ) DOMINION VOTING SYSTEMS ) CORPORATION ) c/o Cogency Global ) 1025 Vermont Ave, NW, Ste. 1130 ) Washington, DC 20005, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Case No. ) HERRING NETWORKS, INC., d/b/a ) ONE AMERICA NEWS NETWORK ) 101 Constitution Ave., NW ) Washington, DC 20001, ) ) CHARLES HERRING ) 17353 Circa Oriente ) Rancho Santa Fe, California 92067, ) ) ROBERT HERRING, SR. ) 4289 Rancho Las Brisas Trail ) San Diego, California 92130, ) ) CHANEL RION ) 3211 Cherry Hill Lane, NW ) Washington, DC 20007, ) ) and ) ) CHRISTINA BOBB ) 565 Pennsylvania Ave., NW ) Apt. 803 ) Washington, DC 20001, ) ) Defendants. ) ) Case 1:21-cv-02130-CJN Document 1 Filed 08/10/21 Page 2 of 213 COMPLAINT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL April 18, 2021: “‘The majority of people [at OAN] did not believe the voter fraud claims being run on the air.’ . Mr. Golingan, the producer, said some OAN employees had hoped Dominion would sue the channel. ‘A lot of people said, “This is insane, and maybe if they sue us, we’ll stop putting stories like this out,”’ he said.” Former OAN Producer Marty Golingan, quoted in the New York times, and fired by OAN the day after the statements were published 1. On the actual facts, the November 2020 election was a huge success for Dominion. In jurisdiction after jurisdiction, in 28 states, in the midst of a highly disruptive pandemic, Dominion’s voting machines facilitated efficient and reliable voting with accurate tallying of votes. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment. -

Negotiating News at the White House

"Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House CAROL PAULI* I. INTRODUCTION II. WHITE HOUSE PRESS BRIEFINGS A. PressBriefing as Negotiation B. The Parties and Their Power, Generally C. Ghosts in the Briefing Room D. Zone ofPossibleAgreement III. THE NEW ADMINISTRATION A. The Parties and Their Power, 2016-2017 B. White House Moves 1. NOVEMBER 22: POSITIONING 2. JANUARY 11: PLAYING TIT-FOR-TAT a. Tit-for-Tat b. Warning or Threat 3. JANUARY 21: ANCHORING AND MORE a. Anchoring b. Testing the Press c. Taunting the Press d. Changingthe GroundRules e. Devaluing the Offer f. MisdirectingPress Attention * Associate Professor, Texas A&M University School of Law; J.D. Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law; M.S. Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism; former writer and editor for the Associated Press broadcast wire; former writer and producer for CBS News; former writer for the Evansville (IN) Sunday Courier& Press and the Decatur (IL) Herald-Review. I am grateful for the encouragement and generosity of colleagues at Texas A&M University School of Law, especially Professor Cynthia Alkon, Professor Susan Fortney, Professor Guillermo Garcia, Professor Neil Sobol, and Professor Nancy Welsh. I also appreciate the helpful comments of members of the AALS section on Dispute Resolution, particularly Professor Noam Ebner, Professor Caroline Kaas, Professor David Noll, and Professor Richard Reuben. Special thanks go to longtime Associated Press White House Correspondent, Mark Smith, who kindly read a late draft of this article, made candid corrections, and offered valuable observations from his experience on the front lines (actually, the second row) of the White House press room. -

(State Bar No. 234981) [email protected] 3 COLIN H

Case 3:19-cv-01713-BAS-AHG Document 19 Filed 12/02/19 PageID.103 Page 1 of 26 1 LOUIS R. MILLER (State Bar No. 54141) [email protected] 2 AMNON Z. SIEGEL (State Bar No. 234981) [email protected] 3 COLIN H. ROLFS (State Bar No. 280654) [email protected] 4 JUSTIN P. MCCARTHY (State Bar No. 317169) [email protected] 5 MILLER BARONDESS, LLP 1999 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 1000 6 Los Angeles, California 90067 Telephone: (310) 552-4400 7 Facsimile: (310) 552-8400 8 Attorneys for Plaintiff Herring Networks, Inc. 9 10 11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 12 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 14 HERRING NETWORKS, INC., CASE NO. 3:19-cv-01713-BAS-BGS 15 Plaintiff, Assigned for All Purposes to: Hon. Cynthia Bashant 16 v. PLAINTIFF HERRING 17 RACHEL MADDOW; COMCAST NETWORKS, INC.’S OPPOSITION CORPORATION; NBC UNIVERSAL TO DEFENDANTS’ SPECIAL 18 MEDIA, LLC; AND MSNBC CABLE MOTION TO STRIKE LLC, 19 NO ORAL ARGUMENT UNLESS Defendants. REQUESTED BY THE COURT 20 [Filed Concurrently with Declaration of 21 Charles Herring; Declaration of Professor Stefan Th. Gries and 22 Declaration of Amnon Z. Siegel] 23 Action Filed: September 9, 2019 24 Hearing Date: December 16, 2019 Trial Date: None 25 26 27 28 441437.6 Case No. 3:19-cv-01713-BAS-BGS HERRING NETWORKS, INC.’S OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANTS’ SPECIAL MOTION TO STRIKE Case 3:19-cv-01713-BAS-AHG Document 19 Filed 12/02/19 PageID.104 Page 2 of 26 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 3 I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................1 4 II. -

Channel Lineup Blackstone & Crewe

2021 CHANNEL LINEUP BLACKSTONE & CREWE PREMIUM CHANNELS HBO*† 300 HBO 302 HBO2 304 HBO COMEDY 291 HBO HD 301 HBO FAMILY 303 HBO SIGNATURE 305 HBO ZONE SHOWTIME & THE MOVIE CHANNEL*† 310 SHOWTIME 313 SHO EXTREME 316 SHOWTIME FAMILY 318 THE MOVIE CHANNEL 294 SHOWTIME HD 311 SHO 2 314 SHO NEXT ZONE 319 THE MOVIE CHANNEL 312 SHOWTIME SHOWCASE 315 SHO WOMEN 317 FLIX XTRA CINEMAX*† 320 CINEMAX 322 ACTIONMAX 324 MOVIEMAX 326 5STARMAX 292 CINEMAX HD 321 MOREMAX 323 THRILLERMAX 325 MAX Latino 327 OUTERMAX ENCORE / STARZ*† 330 STARZ ENCORE 333 STARZ ENCORE 335 STARZ ENCORE 338 STARZ EDGE 342 STARZ COMEDY 331 STARZ ENCORE ACTION SUSPENSE WESTERN 339 STARZ KIDS & FAMILY 293 STARZ HD 332 STARZ ENCORE 334 STARZ ENCORE 336 STARZ ENCORE FAMILY 340 STARZ IN BLACK CLASSIC BLACK 337 STARZ 341 STARZ CINEMA FAN’S CHOICE*† 360 NFL RedZone HD 364 Game+ HD 366 TVG2 369 Cars TV HD 361 Fox Soccer Plus HD 365 World Fishing 367 Pursuit HD 370 Ride TV HD 363 Fight Network HD Network HD 368 Eleven Sports HD PAY-PER-VIEW* / MUSIC CHANNELS* 350-354 Pay-Per-View 901-950 Music Choice STARTER* 2 Channel Guide 14 INSP 168 Charge TV-WRLH 205 QVC HD 212 NBC-WWBT 4 Local Access 15 CSPAN 169 MyNetworkTV/ 206 CBS-WTVR (Richmond) HD 5 QVC 16 CSPAN2 TBD-WRLH (Richmond) HD 214 QVC2 HD 6 CBS-WTVR (Richmond) 17 TBN 170 Antenna TV-WTVR 207 PBS-WCVE 218 The Weather 7 PBS-WCVE (Richmond) 18 HSN 171 CBS6 Xtra-WTVR (Richmond) HD Channel HD 8 ABC-WRIC (Richmond) 19 The Weather Channel 172 Justice Network - 208 ABC-WRIC 297 HSN HD 9 FOX-WRLH (Richmond) 80 ODAC Channel WWBT (Richmond) HD 11 ALIVE TV 99 Quick Tips 173 Court TV 209 FOX-WRLH 12 NBC-WWBT (Richmond) 157 Comet-WRLH Mysteries-WWBT (Richmond) HD 13 MeTV-WWBT 166 GetTV-WRIC 211 INSP HD HD Channels require a converter * Converter is required † A subscription to a premium channel is required. -

US Mainstream Media Index May 2021.Pdf

Mainstream Media Top Investors/Donors/Owners Ownership Type Medium Reach # estimated monthly (ranked by audience size) for ranking purposes 1 Wikipedia Google was the biggest funder in 2020 Non Profit Digital Only In July 2020, there were 1,700,000,000 along with Wojcicki Foundation 5B visitors to Wikipedia. (YouTube) Foundation while the largest BBC reports, via donor to its endowment is Arcadia, a Wikipedia, that the site charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and had on average in 2020, Peter Baldwin. Other major donors 1.7 billion unique visitors include Google.org, Amazon, Musk every month. SimilarWeb Foundation, George Soros, Craig reports over 5B monthly Newmark, Facebook and the late Jim visits for April 2021. Pacha. Wikipedia spends $55M/year on salaries and programs with a total of $112M in expenses in 2020 while all content is user-generated (free). 2 FOX Rupert Murdoch has a controlling Publicly Traded TV/digital site 2.6M in Jan. 2021. 3.6 833,000,000 interest in News Corp. million households – Average weekday prime Rupert Murdoch Executive Chairman, time news audience in News Corp, son Lachlan K. Murdoch, Co- 2020. Website visits in Chairman, News Corp, Executive Dec. 2020: FOX 332M. Chairman & Chief Executive Officer, Fox Source: Adweek and Corporation, Executive Chairman, NOVA Press Gazette. However, Entertainment Group. Fox News is owned unique monthly views by the Fox Corporation, which is owned in are 113M in Dec. 2020. part by the Murdoch Family (39% share). It’s also important to point out that the same person with Fox News ownership, Rupert Murdoch, owns News Corp with the same 39% share, and News Corp owns the New York Post, HarperCollins, and the Wall Street Journal.