Getting on Their Good Side the Oft-Scorned Horseshoe Crab Is Winning Human Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insect and Arachnid Collection Quest

INSECT AND ARACHNID COLLECTION QUEST This quest encourages you to explore and investigate what you might normally ignore. To complete this quest, find 10 different species of insects, at least one species of arachnids, preserve the insects and arachnids, and then pin your collection. Once you have completed these steps, label the parts of the insects and the arachnids. At the end of this quest, you will receive a “Critters of Texas” pocket guide and points to use toward the trade items at Texas Nature Traders. STEP 1: Identify and collect 10 different insect species. The collection should include five different families of insects. STEP 2: Identify and collect at least one species of arachnids. STEP 3: Perform the proper procurement and preservation methods. STEP 4: Properly pin insects and arachnids. STEP 5: Label parts of insects: head, thorax and abdomen. Label parts of arachnids: cephalothorax and abdomen. STEP 6: Bring in the collection to Texas Nature Traders. FUN FACTS AND ANSWERS TO CURIOUS QUESTIONS What is the difference between insects and arachnids? o Mostly anatomical, such as: arachnids lack antennae; insects have mandibles and arachnids have fangs; insects have six legs and arachnids have eight. Can insects hear? o Yes. Insects use sounds to communicate and navigate their environment. Most insects have a pair of tympanal organs. In many cases, there is also a receptor on the antennae called the Johnston’s organ, which also collects sound vibrations. Are insects/arachnids considered animals? o Yes, they belong to the kingdom Animalia. Where in the world has the most mosquitoes? o Alaska has the most mosquitoes due to the melting snow, which leaves large amounts of standing water – perfect conditions for mosquito breeding. -

Homeowner Guide to Scorpions and Their Relatives

HOMEOWNER Guide to by Edward John Bechinski, Dennis J. Schotzko, and Craig R. Baird CIS 1168 Scorpions and their relatives “Arachnid” is the scientific classification category for all eight-legged relatives of insects. Spiders are the biggest group of arachnids, with nearly 3800 species known from the U.S and Canada. But the arachnid category includes other types of eight-legged creatures that sometime cause concern. Some of Idaho’s non-spider arachnids – such as scorpions -- pose potential threats to human health. Two related non-spider arachnids – sun scorpions and pseudoscorpions – look fearsome but are entirely harmless. This publication will help you identify these three groups and understand the threats they pose. All three of these groups almost always are seen as lone individuals that do not require any control. Scorpions IDENTIFICATION AND BIOLOGY FLUORESCENT SCORPIONS Scorpions are easily identified by their claw-like pincers at the The bodies of some scorpions – normally pale tan to darker red-brown – front of the head and their thin, many-segmented abdomen that glow yellow-green when exposed to ultraviolet light. Even fossils millions ends in an enlarged bulb with a curved sting at the tip (figure 1). of years old fluoresce under ultraviolet light. Sun spiders similarly glow yel- Five species ranging in size from 2 to 7 inches long occur in low-green under UV light. Idaho. Scorpions primarily occur in the sagebrush desert of the southern half of Idaho, but one species – the northern scorpion (Paruroctonus boreus)– occurs as far north as Lewiston, along the Snake River canyon of north-central Idaho. -

Phylogenomic Resolution of Sea Spider Diversification Through Integration Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929612; this version posted February 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Phylogenomic resolution of sea spider diversification through integration of multiple data classes 1Jesús A. Ballesteros†, 1Emily V.W. Setton†, 1Carlos E. Santibáñez López†, 2Claudia P. Arango, 3Georg Brenneis, 4Saskia Brix, 5Esperanza Cano-Sánchez, 6Merai Dandouch, 6Geoffrey F. Dilly, 7Marc P. Eleaume, 1Guilherme Gainett, 8Cyril Gallut, 6Sean McAtee, 6Lauren McIntyre, 9Amy L. Moran, 6Randy Moran, 5Pablo J. López-González, 10Gerhard Scholtz, 6Clay Williamson, 11H. Arthur Woods, 12Ward C. Wheeler, 1Prashant P. Sharma* 1 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, USA 2 Queensland Museum, Biodiversity Program, Brisbane, Australia 3 Zoologisches Institut und Museum, Cytologie und Evolutionsbiologie, Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany 4 Senckenberg am Meer, German Centre for Marine Biodiversity Research (DZMB), c/o Biocenter Grindel (CeNak), Martin-Luther-King-Platz 3, Hamburg, Germany 5 Biodiversidad y Ecología Acuática, Departamento de Zoología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain 6 Department of Biology, California State University-Channel Islands, Camarillo, CA, USA 7 Départment Milieux et Peuplements Aquatiques, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France 8 Institut de Systématique, Emvolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Concarneau, France 9 Department of Biology, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, USA Page 1 of 31 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929612; this version posted February 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

Arachnid Or Insect?

Suggested levels for Guided Reading, DRA,™ Lexile,® and Reading Recovery™ are provided Life Science in the Pearson Scott Foresman Leveling Guide. ArachnidArachnid oror Insect?Insect? Comprehension Genre Text Features Skills and Strategy Expository • Compare and • Captions nonfiction Contrast • Labels • Main Idea • Callouts • Summarize Scott Foresman Reading Street 2.3.3 ISBN-13: 978-0-328-50838-9 ISBN-10: 0-328-50838-1 9 0 0 0 0 by Kristin Cashore 9 780328 508389 50838_CVR.indd Page 1-2 3/19/13 2:34 AM gg-041 /110/SF00327_R4/sf00327_1of1/work%250/indd%250/SF_RE_TX:NL_Leveled_G2/On/2.3.3O%2 ... Vocabulary been Arachnid believe caught or finally Insect? today tomorrow whatever Word count: 284 by Kristin Cashore Note: The total word count includes words in the running text and headings only. Numerals and words in chapter titles, captions, labels, diagrams, charts, graphs, sidebars, and extra features are not included. Glenview, Illinois • Boston, Massachusetts • Chandler, Arizona Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 50838_001-012.indd Page 1 3/19/13 2:22 AM gg-041 /110/SF00327_R4/sf00327_1of1/work%250/indd%250/SF_RE_TX:NL_Leveled_G2/On/2.3.3O%2 ... Many people believe that all bugs and creepy crawly things are insects. This is not true! A spider is not an insect. It is an arachnid. What is the difference? Photographs Every effort has been made to secure permission and provide appropriate credit for photographic material. The publisher deeply regrets any omission and pledges to correct errors called to its attention in subsequent editions. Unless otherwise acknowledged, all photographs are the property of Pearson Education, Inc. -

Horseshoe Crab Genomes Reveal the Evolutionary Fates of Genes and Micrornas After 2 Three Rounds (3R) of Whole Genome Duplication

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.16.045815; this version posted April 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Horseshoe crab genomes reveal the evolutionary fates of genes and microRNAs after 2 three rounds (3R) of whole genome duplication 3 Wenyan Nong1,^, Zhe Qu1,^, Yiqian Li1,^, Tom Barton-Owen1,^, Annette Y.P. Wong1,^, Ho 4 Yin Yip1, Hoi Ting Lee1, Satya Narayana1, Tobias Baril2, Thomas Swale3, Jianquan Cao1, 5 Ting Fung Chan4, Hoi Shan Kwan5, Ngai Sai Ming4, Gianni Panagiotou6,16, Pei-Yuan Qian7, 6 Jian-Wen Qiu8, Kevin Y. Yip9, Noraznawati Ismail10, Siddhartha Pati11, 17, 18, Akbar John12, 7 Stephen S. Tobe13, William G. Bendena14, Siu Gin Cheung15, Alexander Hayward2, Jerome 8 H.L. Hui1,* 9 10 1. School of Life Sciences, Simon F.S. Li Marine Science Laboratory, State Key Laboratory of 11 Agrobiotechnology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China 12 2. University of Exeter, United Kingdom 13 3. Dovetail Genomics, United States of America 14 4. State Key Laboratory of Agrobiotechnology, School of Life Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 15 China 16 5. School of Life Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China 17 6. School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, China 18 7. Department of Ocean Science and Hong Kong Branch of Southern Marine Science and Engineering 19 Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou), Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, China 20 8. Department of Biology, Hong Kong Baptist University, China 21 9. -

Are You One of Us? Insects | Grades 5 & 6

ARE YOU ONE OF US? INSECTS | GRADES 5 & 6 Skills Subjects Sorting, classifying, comparing Science National Science Standard Time Content Standard C: Life Science Preparation: 10 minutes Students should develop an understanding of the characteristics of Teaching: 60 minutes living organisms. Evaluation: 10 minutes Content Standard G: History and Nature of Science Vocabulary Students should develop an understanding of science as a human Definitions on Page 4 of Lesson endeavour. systematics mammal Objectives exoskeleton • Students will learn that scientists classify living things according to vertebrae similarities and differences. arthropod • Students will be able to list the characteristics of arthropods. thorax • Students will be able to list the characteristics of insects. abdomen • Students will able to name the five classes of arthropods and give an antennae example of an arthropod in each of the classes. millipede Assessment centipede Given pictures or models of arthropods, students will be able to sort crustacean them into the classes. arachnid Materials • “Invertebrate Photographs” template • Chart paper or whiteboard • Plastic arthropod models (optional) Background One of the most important jobs of being a scientist is to sort and classify. The science of classification is called systematics. Systematics gives scientists the tools to communicate clearly about the natural world. Living organisms are grouped according to how closely related they are (their evolutionary history). These groups start out very large and become increasingly specific until finally scientists name individual species. Each species has a scientific name that is recognized anywhere in the world no matter what language is spoken. Most people think that mammals are the most important and numerous group of animals on the earth. -

Insects, Spiders and Other Arthropods

Insects, Spiders and Other Arthropods Fourth-Grade Teacher Resource Guide Table of Contents Lesson summary .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Vocabulary ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Language Arts Crossword Puzzle .................................................................................................... 2-3 Language Arts Word Search ........................................................................................................... 4-5 Extension Activities .......................................................................................................................... 6 Education Standards ..................................................................................................................... 7-8 Insects, Spiders and Other Arthropods: Lesson Summary and Vocabulary Lesson Summary: The YSI Insects, Spiders & Other Arthropods program allows students to touch and examine samples of the arthropod phylum while learning about their characteristics and development. The presentation focuses on both instructor-led discussion and hands-on activities. Students will work as a group to assemble an insect and spider, observing the functions and variations in each body part. Discussion will continue as the instructor presents live examples, covering the arthropods’ physical adaptations, diets, -

24.3 Arachnids

24.3 Arachnids KEY CONCEPT Arachnids include spiders and their relatives. 24.3 Arachnids Arachnids are the largest group of chelicerates. • There are three major groups of chelicerates. – horseshoe crabs 24.3 Arachnids Arachnids are the largest group of chelicerates. • There are three major groups of chelicerates. – horseshoe crabs – sea spiders – arachnids 24.3 Arachnids • Chelicerates share several features. – no antennae – Six pair of appendages • four pairs of walking legs • one pair each of chelicerae and pedipalps • Arachnids are a group of chelicerates that live on land. – Fossils dating 400 m.y.a. – eight legs – fanglike pincers fangs poison gland that inject venom – silk glands spinnerets 24.3 Arachnids • Arachnids have four different adaptations that reduce water loss. – waterproof cuticle • Water can’t evaporate across skin – book lungs • Large surface area for gas exchange 24.3 Arachnids – Malpighian tubules • Excretory structure • Minimizes water loss – spiracles • Tiny holes that allow O2 to enter cutilce 24.3 Arachnids “How do the features of an arachnid allow it to live on land?” 24.3 Arachnids Arachnids have evolved into a diverse group. • All spiders make silk and produce venom. 24.3 Arachnids • Silk is used for: – Building webs – Egg cases – Wrapping prey –Shelters – Safety line 24.3 Arachnids • Venom… – All are hunters – Inject by chelicerae – Neurotoxin or hematoxin – Black Widow & Brown Recluse 24.3 Arachnids • Identify the parts of a spider. 24.3 Arachnids Bell Ringer • 1-What is silk used for? • 2-What is venom used for? • 3-What are spiracles? • 4-How are spiracles an adaptation to reduce water loss? • 5-Are all arachnids spiders? If not what else is an arachnid? 24.3 Arachnids Arachnids have evolved into a diverse group. -

Geological History and Phylogeny of Chelicerata

Arthropod Structure & Development 39 (2010) 124–142 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Arthropod Structure & Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/asd Review Article Geological history and phylogeny of Chelicerata Jason A. Dunlop* Museum fu¨r Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiversity at the Humboldt University Berlin, Invalidenstraße 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany article info abstract Article history: Chelicerata probably appeared during the Cambrian period. Their precise origins remain unclear, but may Received 1 December 2009 lie among the so-called great appendage arthropods. By the late Cambrian there is evidence for both Accepted 13 January 2010 Pycnogonida and Euchelicerata. Relationships between the principal euchelicerate lineages are unre- solved, but Xiphosura, Eurypterida and Chasmataspidida (the last two extinct), are all known as body Keywords: fossils from the Ordovician. The fourth group, Arachnida, was found monophyletic in most recent studies. Arachnida Arachnids are known unequivocally from the Silurian (a putative Ordovician mite remains controversial), Fossil record and the balance of evidence favours a common, terrestrial ancestor. Recent work recognises four prin- Phylogeny Evolutionary tree cipal arachnid clades: Stethostomata, Haplocnemata, Acaromorpha and Pantetrapulmonata, of which the pantetrapulmonates (spiders and their relatives) are probably the most robust grouping. Stethostomata includes Scorpiones (Silurian–Recent) and Opiliones (Devonian–Recent), while -

116 the Northern Scorpion (Paruroctonus Boreus) Is A

BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY IN THE NORTHERN SCORPION (POSTER) Synda Boumediene, Montana State University, Billings Summit Parcell, Montana State University, Billings Lea Henderson, Montana State University, Billings Sarah Gallup, Montana State University, Billings Colleen Tallon, Montana State University, Billings Amanda Klein, Montana State University, Billings James Barron, Department of Biological and Physical Sciences, Montana State University, Billings The Northern Scorpion (Paruroctonus boreus) is a predatory arachnid. Although occurring at relatively high densities in local areas, conspecifics have seldom been observed sharing cover items. We investigated territoriality of scorpions by analyzing pairs of scorpions introduced into a habitat with a single, small cover item. We used mono- and bisexual pairs, similar and differently sized pairs, and pairs from the same or different populations. Scorpions were collected from two populations in south-central Montana. Results indicate that scorpions do interact over cover items, though not to the extent that we had anticipated. When scorpions were housed singly, they spent 80% of their time under cover. When size-matched pairs were offered a single cover item, up to 60% of the time 116 © Intermountain Journal of Sciences, Vol. 23, No. 1-4, December 2017 © Intermountain Journal of Sciences, Vol. 23, No. 1-4, December 2017 117 at least one scorpion was not under cover. Further, when differently-sized scorpions were paired, a similar result obtained with the larger scorpion excluding the smaller most often. Interestingly, these results all differed by population and sex. Scorpions from the naturally more-dense population excluded others more frequently than scorpions from the less-dense population. Additionally, males excluded other males more frequently than mixed-sex pairings excluded one sex or the other, or than females excluded other females. -

Arthropods Insects, Arachnids, and Crustaceans

Arthropods Insects, Arachnids, and Crustaceans Reading and Discussion Arthropods are animals that are a part of the Phylum Arthropoda, which means “jointed feet”. They are known by their jointed limbs and cuticles. An arthropod's body consists of segments, and each segment has a pair of appendages. Arthropods are invertebrates, which means that they do not have a backbone or spinal column. There are over one million species of arthropods. The arthropod phylum includes: 1. insects 2. arachnids 3. crustaceans Insects are one of the most diverse groups of animals. They have segmented bodies that are supported by an exoskeleton. An exoskeleton is an external skeleton that protects and supports an animal's body. An insect's hard exoskeleton is primarily made up of something called chitin. The body of an insect is made up of three segments: a head a thorax an abdomen The head supports an insect's antennae. The thorax is the segment that includes the insect's six legs. Not all insects have wings, but, if they do have wings, these wings are also located on the thorax. The abdomen section has most of the digestive, respiratory, excretory, and reproductive systems. Insects do not use lungs to breathe. Instead, they have a system of internal sacs and tubes that help to deliver oxygen directly to their body tissues. Arachnids are mainly land animals, but they can also be found in freshwater environments. Most arachnids have eight legs. Their legs come in pairs. The first pair is known as the chelicerae and is used primarily for feeding and defense. -

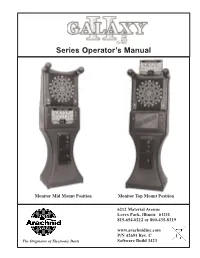

Series Operator's Manual

Series Operator’s Manual Monitor Mid Mount Position Monitor Top Mount Position 6212 Material Avenue Loves Park, Illinois 61111 815-654-0212 or 800-435-8319 www.arachnidinc.com P/N 42691 Rev. C The Originator of Electronic Darts Software Build 3423 GALAXY II PURCHASE AND LICENSE AGREEMENT TERMS AND CONDITIONS 1. General Provisions. These terms and conditions (this “Agreement”) govern all orders from Arachnid Inc.’s customer (“Buyer”) to Arachnid, Inc. (“Arachnid”) for, and sales and the grant of related licenses by Arachnid to Buyer of, the Arachnid product referred to as the “GALAXY II” and its software (the “Product”). With respect to the Products, the terms and conditions of this Agreement shall (i) supersede any conflicting or additional terms contained in any advertisement, quotation, purchase order, confirmation, acknowledgment or other document or communication heretofore or hereafter between Buyer and Arachnid, and (ii) apply whether or not Arachnid or Buyer or both specifically reference this Agreement in any document concerning any order for or sale of the Products, unless Arachnid and Buyer expressly otherwise agree in a writing signed and delivered by each of them to the other which specifically references this Agreement by date and describes which terms and conditions of this Agreement are excepted and super- seded. Arachnid’s acceptance of any order by Buyer for a Product is expressly conditioned upon the applicability of this Agreement. All orders are subject to Arachnid’s approval, including approval of credit terms. EXCEPT TO THE EXTENT LICENSED IN SEC- TION 2 BELOW, BUYER IS NOT ACQUIRING FROM ARACHNID ANY OWNERSHIP OR OTHER RIGHTS IN AND TO ANY OF THE SOFTWARE OR OTHER INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY USED TO OPERATE, OR COMPRISING ANY PART OF, THE PROD- UCTS.