The Juilliard String Quartet Sessions / Wolpe / Babbitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morton Feldman: a Celebration of His 80Th Birthday

Morton Feldman : A Celebration of His 80th Birthday Curated by John Bewley June 1 – September 15, 2006 Case 1 Morton Feldman was born January 12, 1926 in New York City to Irving and Frances Feldman. He grew up in Woodside, Queens where his father established a company that manufactured children’s coats. His early musical education consisted of piano lessons at the Third Street Settlement School in Manhattan and beginning at age twelve, with Vera Maurina Press, an acquaintance of the Russian composer, Alexander Scriabin, and a student of Ferruccio Busoni, Emil von Sauer, and Ignaz Friedman. Feldman began composing at age nine but did not begin formal studies until age fifteen when he began compositional studies with Wallingford Riegger. Morton Feldman, age 13, at the Perisphere, New York World’s Fair, 1939? Unidentified photographer Rather than pursuing a college education, Feldman chose to study music privately while he continued working for his father until about 1967. After completing his studies in January 1944 at the Music and Arts High School in Manhattan, Feldman studied composition with Stefan Wolpe. It was through Wolpe that Feldman met Edgard Varèse whose music and professional life were major influences on Feldman’s career. Excerpt from “I met Heine on the Rue Furstenburg”, Morton Feldman in conversation with John Dwyer, Buffalo Evening News, Saturday April 21, 1973 Let me tell you about the factory and Lukas Foss (composer and former Buffalo Philharmonic conductor). The plant was near La Guardia airport. Lukas missed his plane one day and he knew I was around there, so he called me up and invited me to lunch. -

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

100Th Season Anniversary Celebration Gala Program At

Friday Evening, May 5, 2000, at 7:30 Peoples’ Symphony Concerts 100th Season Celebration Gala This concert is dedicated with gratitude and affection to the many artists whose generosity and music-making has made PSC possible for its first 100 years ANTON WEBERN (1883-1945) Langsaner Satz for String Quartet (1905) Langsam, mit bewegtem Ausdruck HUGO WOLF (1860-1903) “Italian Serenade” in G Major for String Quartet (1892) Tokyo String Quartet Mikhail Kopelman, violin; Kikuei Ikeda, violin; Kazuhide Isomura, viola; Clive Greensmith, cello LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Trio for piano, violin and cello in B-flat Major Op. 11 (1798) Allegro con brio Adagio Allegretto con variazione The Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio Joseph Kalichstein, piano; Jamie Laredo, Violin; Sharon Robinson. cello GYORGY KURTAG (b. 1926) Officium breve in memoriam Andreae Szervánsky 1 Largo 2 Piú andante 3 Sostenuto, quasi giusto 4 Grave, moto sostenuto 5 Presto 6 Molto agitato 7 Sehr fliessend 8 Lento 9 Largo 10 Sehr fliessend 10a A Tempt 11 Sostenuto 12 Sostenuto, quasi guisto 13 Sostenuto, con slancio 14 Disperato, vivo 15 Larghetto Juilliard String Quartet Joel Smirnoff, violin; Ronald Copes, violin; Samuel Rhodes, viola; Joel Krosnick, cello GEORGE GERSHWIN (1898-1937) arr. PETER STOLTZMAN Porgy and Bess Suite (1935) It Ain’t Necessarily So Prayer Summertime Richard Stoltzman, clarinet and Peter Stoltzman, piano intermission MICHAEL DAUGHERTY (b. 1954) Used Car Salesman (2000) Ethos Percussion Group Trey Files, Eric Phinney, Michael Sgouros, Yousif Sheronick New York Premiere Commissined by Hancher Auditorium/The University of Iowa LEOS JANÁCEK (1854-1928) Mládi (Youth) Suite for Wind Instruments (1924) Allegro Andante sostenuto Vivace Allegro animato Musicians from Marlboro Tanya Dusevic Witek, flute; Rudolph Vrbsky, oboe; Anthony McGill, clarinet; Jo-Ann Sternberg, bass clarinet; Daniel Matsukawa, bassoon; David Jolley, horn ZOLTAN KODALY (1882-1967) String Quartet #2 in D minor, Op. -

Welcome Anthea Kreston! the Artemis Quartet Welcomes Its New Member

Welcome Anthea Kreston! The Artemis Quartet welcomes its new member Berlin, 18 January 2016 In the past six months, amidst mourning the death of Friedemann Weigle, the Artemis Quartet also came to the decision of continuing its work as an ensemble. Now, the Artemis Quartet is pleased to announce its new member: the American violinist Anthea Kreston, who will take over the second violin position with immediate effect. In a musical chairs scenario, Gregor Sigl will assume the viola position in the quartet. Andrea Kreston, born in Chicago, studied with Felix Galimir and Ida Kavafian at the renowned Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, as well as chamber music with the Vermeer Quartet and Emerson String Quartet. Anthea Kreston was a member of the Avalon Quartet - with whom she won the ARD Competition in 2000 - for seven years. In 1999, she founded the Amelia Piano Trio. She has given many concerts in the United States and Europe with both ensembles. Eckart Runge and Anthea Kreston have known each other for twenty years. They met, as members of different ensembles, at a masterclass given by the Juilliard String Quartet. Eckart Runge: “Already then, Anthea struck me as an extraordinarily brilliant musician and someone who has a big personality. She applied for the available position, travelled to the audition from the West Coast [of the United States] and impressed us with her warm-heartedness, boundless energy and - above all - her fantastic qualities as a musician and violinist. All three of us immediately felt that, in her own way, Anthea reflects the soul of Friedemann and will bring new energy to our quartet.” Anthea Kreston: “It is with a full heart that I join the Artemis Quartet, my favourite quartet since we were all students together at the Juilliard Quartet Seminar 20 years ago. -

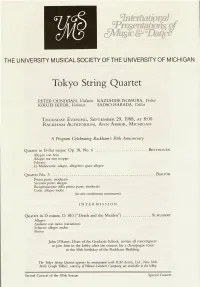

Tokyo String Quartet

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Tokyo String Quartet PETER OUNDJIAN, Violinist KAZUHIDE ISOMURA, Violist KIKUEI IKEDA, Violinist SADAO HARADA, Cellist THURSDAY EVENING, SEPTEMBER 29, 1988, AT 8:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN A Program Celebrating Rackham's 50th Anniversary Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 18, No. 6 .......................... BEETHOVEN Allegro con brio Adagio ma non troppo Scherzo La Malinconia: adagio, allegretto quasi allegro Quartet No. 3 ................................................... BARTOK Prima parte: moderate Seconda parte: allegro Ricapitulazione della prima parte: moderate Coda: allegro molto (in one continuous movement) INTERMISSION Quartet in D minor, D. 810 ("Death and the Maiden") .............. SCHUBERT Allegro Andante con moto (variations) Scherzo: allegro molto Presto John D'Arms, Dean of the Graduate School, invites all concertgoers to join him in the lobby after the concert for a champagne toast to the 50th birthday of the Rackham Building. The Tokyo String Quartet appears by arrangement with /CM Artists, Ltd., New York. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner-Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Second Concert of the 110th Season Special Concert PROGRAM NOTES Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 18, No. 6 .............. LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Beethoven's Opus 18 consists of six string quartets that were written mostly in 1799, though they were not published until 1801. This was a successful and contented period for the young composer, who was not yet troubled by any signs of his impending tragic deafness and was achieving a respected reputation as a pianist and composer in musical and aristocratic circles in Vienna. A composer writing in this medium at that time could not fail to have been constantly aware of the great masterpieces of eighteenth-century quartet literature that had been produced by Mozart and Haydn. -

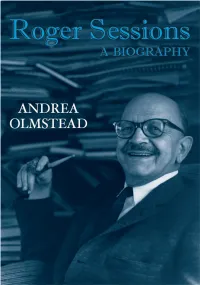

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Quatuor Ébène Pierre Colombet Violin • Gabriel Le Magadure Violin Marie Chilemme Viola • Raphaël Merlin Cello

Wednesday 12 December 2018 7.30pm Quatuor Ébène Pierre Colombet violin • Gabriel Le Magadure violin Marie Chilemme viola • Raphaël Merlin cello Ludwig van Beethoven String Quartet in F Op. 18 No. 1 Johannes Brahms String Quartet in C minor Op. 51 No. 1 I n t e r v a l (20 minutes) Ludwig van Beethoven String Quartet in F Op. 135 This evening’s concert will be streamed live, and will be available to watch afterwards on the Wigmore Hall website. PROGRAMME: £3 CAVATINA Chamber Music Trust has donated free tickets for 8-25 year-olds for the concert on 12 December 2018. For details of future concerts please call the Box Office on 020 7935 2141. 2018 cover-autumn test print.indd 1 29/08/2018 10:28 Ludwig van Beethoven Beethoven arrived in Vienna in 1792, a year after Mozart’s tragic death. The young, (1770–1827) Bonn-born composer was effectively travelling to the Habsburg capital to take up where the late, lamented composer had String Quartet in F Op. 18 No. 1 left off. He even carried a letter to that end, (1798–1800) written by his friend Count von Waldstein: Allegro con brio ‘You are going to Vienna in fulfilment Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato of your long-frustrated wishes. The Scherzo. Allegro molto Genius of Mozart is still mourning and Allegro weeping the death of her pupil. She found a refuge but no occupation with the inexhaustible Haydn; through him Johannes Brahms she wishes once more to form a union (1833–1897) with another. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

Juilliard String Quartet

JUILLIARD STRING QUARTET ARETA ZHULLA - VIOLIN RONALD COPES - VIOLIN ROGER TAPPING - VIOLA ASTRID SCHWEEN - VIOLONCELLO „Decisive and uncompromising...Juilliard’s confidently thoughtful approach, rhythmic acuity and ensemble precision were on full display." – The Washington Post With unparalleled artistry and enduring vigor, the Juilliard String Quartet continues to inspire audiences around the world. Founded in 1946 and hailed by the Boston Globe as “the most important American quartet in history,” the Juilliard draws on a deep and vital engagement to the classics, while embracing the mission of championing new works, a vibrant combination of the familiar and the daring. Each performance of the Juilliard Quartet is a unique experience, bringing together the four members’ profound understanding, total commitment, and unceasing curiosity in sharing the wonders of the string quartet literature. Ms. Areta Zhulla joins the Juilliard Quartet as first violinist beginning this 2018-19 season which includes concerts in Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, London, Oslo, Athens, Vancouver, Toronto and New York, with many return engagements all over the USA. The season will also introduce a newly commissioned String Quartet by the wonderful young composer, Lembit Beecher, and some piano quintet collaborations with the celebrated Marc-André Hamelin. In performance, recordings and incomparable work educating the major artists and quartets of our time, the Juilliard String Quartet has carried the banner of the United States and the Juilliard School throughout the world. Having recently celebrated its 70th anniversary, the Juilliard String Quartet marked the 2017-18 season with return appearances in Seattle, Santa Barbara, Pasadena, Memphis, Raleigh, Houston, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen. It continued its acclaimed annual performances in Detroit and Philadelphia, along with numerous concerts at home in New York City, including appearances at Lincoln Center and Town Hall. -

9'; 13 November 30, Jazz Innovations, Part 1

Lim received his fonnal. training at Indiana University, where he studied with the legendary violinist ~d teacher Josef Gingold. While at Indiana, he won First Prize in the school's Violin Concerto Competition and served on the faculty as a Visiting Lecturer. Lim later studied cham~ ber music at the Juilliard School and taught there as an assistant to the Juilliard String Quartet. No PI CI"(.. C D :::n= Lim has recorded for DreamWorks, Albany Records, CR!, Bayer GI rc... C p-:t:F I ~ 02-9resents a Faculty Recital: Records, and Aguava New Music, and appears on numerous television and film soundtracks. He has been heard on NPR programs such as Performance Today and All Things Considered. Lim currently lives in Seattle with his wife, violist Melia Watras. He performs on a violin MELIA WATRAS, VIOLA made by Tomaso Balestrieri in Cremona, Italy in 1774. with 2005~2006 UPCOMING EVENTS Kimberly Russ, piano Information for events listed below is available at www.music. washington. edu Michael Jinsoo Lim, violin and the School ofMusic Events Hotline (206-685-8384). Ticketsfor events listed in Brechemin Auditorium (Music Building) and Walker Ames Room (Kane Hall) go on sale at the door thirty minutes before the •• performance~ Tickets for events in Meany Theater and Meany Studio Theater are available from the UW Arts Ticket Office, 206:543-4880, and at November 8, 2005 7:30 PM Meany THeater the box office thirty minutes before the performance. To request disability accommodation. contact the Disability Services Office at least ten days in advance at 206-543-6450 (voice); 206-543-6452 (lTY); 685-7264 (FAX); or [email protected] (E-mail). -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours.