Nolde’S Search for Ruleless Color

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 • Fourth Sunday After Pentecost

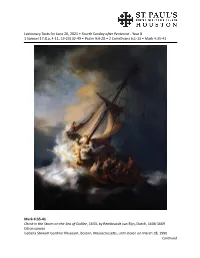

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 •Fourth Sunday after Pentecost- Year B 1 Samuel 17:(1a, 4-11, 19-23) 32-49 • Psalm 9:9-20 • 2 Corinthians 6:1-13 • Mark 4:35-41 Mark 4:35-41 Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633, by Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606-1669 Oil on canvas Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, until stolen on March 18, 1990 Continued Lectionary Texts for the Fourth Sunday after Pentecost• June 20, 2021 • Page 2 In his only painted seascape, Rembrandt dramatically portrays the continuing battle of nature against human frailty, both physical and spiritual. The frightened and overwhelmed disciples struggle to retain control of their fishing boat as huge waves crash over the bow. One disciple is hanging over the side of the boat vomiting. A sail is torn, rope lines are flying loose, disaster is imminent as rocks appear in the left foreground. The dark clouds, the wind, the waves combine to create the terror of the painting and the terror of the disciples. Nature’s upheaval is the cause of, as well as a metaphor for, the fear that grips the disciples. The emotional turbulence is magni- fied by the dramatic impact of the painting, approximately 4’ wide by 5’ high. Jesus, whose face is lightened in the group on the right, remains calm. He woke up and rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, “Peace! Be still!” Then the wind ceased, and there was a dead calm, and he asked the disciples, “Why are you afraid? Have you still no faith?” The face of a 13th disciple looks directly out at the viewer in the horizontal center of the painting. -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

DUTCH and ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850

DUTCH AND ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850 The art and ship models in this station are devoted to the early Dutch and English seascape painters. The historical emphasis here explains the importance of the sea to these nations. Historical Overview: The Dutch: During the 17th century, the Netherlands emerged as one of the great maritime oriented empires. The Dutch Republic was born in 1579 with the signing of the Union of Utrecht by the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands. Two years later the United Provinces of the Netherlands declared their independence from the Spain. They formed a loose confederation as a representative body that met in The Hague where they decided on issues of taxation and defense. During their heyday, the Dutch enjoyed a worldwide empire, dominated international trade and built the strongest economy in Europe on the foundation of a powerful merchant class and a republican form of government. The Dutch economy was based on a mutually supportive industry of agriculture, fishing and international cargo trading. At their command was a huge navy and merchant fleet of fluyts, cargo ships specially designed to sail through the world, which controlled a large percentage of the international trade. In 1595 the first Dutch ships sailed for the East Indies. The Dutch East Indies Company (the VOC as it was known) was established in 1602 and competed directly with Spain and Portugal for the spices of the Far East and the Indian subcontinent. The success of the VOC encouraged the Dutch to expand to the Americas where they established colonies in Brazil, Curacao and the Virgin Islands. -

Emil Nolde’S Fascination with the Fantastical

Hatje Cantz Verlag Mommsenstraße 27 Tel. +49 (0)30 3464678-08 Press Contact: Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH Managing Director: 10629 Berlin Fax +49 (0)30 3289042-62 [email protected] HRB 118521 Thomas Ganske Deutschland www.hatjecantz.de Reg.-Gericht Hamburg Frank-H. Häger UST-ID-Nr.: DE143580256 Dr. Cristina Steingräber Dr. Thomas P.J. Feinen BIZARRE VISUAL WORLDS FROM A CLASSIC ARTIST EMIL NOLDE’S FASCINATION WITH THE FANTASTICAL Luminous flower gardens, wild seascapes, or intense memories of journeys—all the facets of Emil Nolde’s work seem to have been explored. Yet, there’s one theme that has long been basically neglected: the Expressionist painter’s love of the grotesque. Emil Nolde – The Grotesques is the first publication to reveal Nolde’s relationship to the fantastical. Berlin, April 20, 2017 ― It’s surprising that even though the grotesque is a major thematic area of outstanding significance to Emil Nolde (1867 – 1956), there has never been a monograph about this subject. Emil Nolde – The Gotesque’s more than 130 illustrations of intensely colorful paintings, watercolors, and prints invite readers to discover these previously undervalued motifs from Nolde’s oeuvre. References to this obsession are found not only in his autobiography and many of the painter’s letters—even some of his early works are evidence of his particular interest in the fantastical and the grotesque. “In 1894 he began depicting Alpine peaks in the form of grotesque saws,” confirms Christian Ring, director of the Nolde-Stiftung in Seebüll. These were followed by the Bergriesen (mountain giants), which could have sprung from a book of fairy tales, or his Grotesques, a series of etchings. -

Oral History Interview with Richard Ayer, 1964 September 26

Oral history interview with Richard Ayer, 1964 September 26 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview Interview with Richard Ayer Conducted by Mary McChesney In San Francisco, California September 26, 1964 Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Richard Ayer on September 26, 1964. The interview was conducted at 1321 19th Avenue San Francisco, California by Mary McChesney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. MM: - Mary McChesney RA: - Richard Ayer RM: - Robert McChesney MM: Dick, I would like to ask you first where were you born? RA: In San Bernardino. MM: That’s in Southern California? RA: That is in Southern California, yes. MM: In what year was that? RA: That was in 1909. Hardly a man is now alive. It hardly matters now. MM: The date of the recording is September 26, 1964. Dick, where did you receive your art training? RA: Well, I was largely self-taught most of my life and I studied some with Hilaire Hiler and I studied at the California School of Fine Art, as it was. And I don’t know, picked up study with various people who were teaching on the WPA. I don’t know, it was pretty haphazard but it came out pretty consistent. MM: Where did you study with Hiler? RA: Well, I worked with him on the Aquatic Park project and studied color with him on the outside. -

Press Release from Emil Nolde to Neo Rauch Summer Auctions 2021 at Grisebach

Press release From Emil Nolde to Neo Rauch Summer Auctions 2021 at Grisebach At the top of this year’s Summer Auctions (9 to 11 June 2021) is Emil Nolde’s Sonnenblume from 1928. A fine example of Expressionist painting, this spectacular pastose work was once a part of the Salmon Schocken collection and is estimated at EUR 700,000–1,000,000. Yet another 1928 masterpiece will be included in the Selected Works Auction From Emil Nolde to Neo Rauch – Carl Grossberg’s self-portrait, this classic ex- ample of New Objectivity unveils the artist’s fixation with exacting technique, and it’s his sole self-portrait (EUR 300,000–400,000). Nature’s harmony and beauty become tangible in the luminous Reiter in der Allee bei Sakrow, a 1924 landscape painting by Max Liebermann in an exceptionally large format (95.7 x 114.8 cm). This rare motif, the park at Sacrow Palace, is estimated at EUR 500,000–700,000. Alexej von Jawlensky pays homage to the Lago Maggiore with Sommertag in Ascona from 1918, an abstract landscape panorama with a masterfully orchestrated colour scheme (EUR 200,000–300,000). An early work by Franz Marc, Grüne Studie from 1908, is an impressively large format artwork that delivers strikingly powerful colours and bears testimony to the artist’s blossoming creative energy and joie de vivre during his summers in Bavaria (EUR 300,000–500,000). Lovers of Art Nouveau are in for a treat with Heinrich Vogeler’s Träume II (auch ,Früh- ling‘ oder ,Erwartung‘). This iconic work from 1912 captures the ethereal beauty of the artist’s wife and muse, Martha Vogeler (EUR 200,000–300,000). -

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976 Devotion Woodcut, 1912 Schmidt-Rotluff was one of the founding members ofDie Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden in 1905, along with Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Fritz Bleyl, and joined by Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein. The group disbanded in 1913, largely due to their varying styles and independent moves to Berlin, but each remained true to their rejection of European academic painting and conventions in favor of exploring the vitality and directness of non-Western art forms, particularly West African masks and Oceanic art, as well as revitalization of the pre-Renaissance tradition of German woodcuts. Devoción Xilografía, 1912 Schmidt-Rottluff fue uno de los miembros fundadores de Die Brücke (El puente) en Dresde en 1905, junto con Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner y Fritz Bleyl, grupo al que se unieron luego Emil Nolde y Max Pechstein. El grupo se disolvió en 1913, en gran parte debido a la evolución de sus estilos y a los traslados individuales de los artistas a Berlín, pero cada uno de ellos permaneció fiel al rechazo de la pintura y las convenciones academicistas europeas, en favor de la exploración de la vitalidad y la franqueza de formas artísticas no occidentales, especialmente las máscaras de África occidental y el arte de Oceanía, así como de la revitalización de la xilografía alemana de tradición prerrenacentista. Museum purchase through the Earle W. Grant Acquisition Fund, 1975.37 KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF German / Alemán, 1884–1976 Head of a Woman Woodcut, 1909 “I know that I have no program, only the unaccountable longing to grasp what I see and feel, and to find the purest means of expressing it.” Studying Japanese techniques of woodcuts, as well as the techniques of Albrecht Dürer, Paul Gauguin, and Edvard Munch, Schmidt-Rottluff produced powerful images, evoking intense psychological states through the flattening of form and retention of traces of roughly hewn wood blocks. -

Print Format

Allaert van Everdingen (Alkmaar 1621 - Amsterdam 1675) Month of August (Virgo): The Harvest brush and grey and brown wash 11.1 x 12.8 cm (4⅜ x 5 in) The Month of August (Virgo): The Harvest has an extended and fascinating provenance. Sold as part of a complete set of the twelve months in 1694 to the famed Amsterdam writer and translator Sybrand I Feitama (1620-1701), it was passed down through the literary Feitama family who were avid collectors of seventeenth-century Dutch works on paper.¹ The present work was separated from the other months after their 1758 sale and most likely stayed in private collections until 1936 when it appeared in Christie’s London saleroom as part of the Henry Oppenheimer sale. Allaert van Everdingen was an exceptional draughtsman who was particularly skilled at making sets of drawings depicting, with appropriate images and activities, the twelve months of the year.² This tradition was rooted in medieval manuscript illumination, but became increasingly popular in the context of paintings, drawings and prints in the sixteenth century.³ In the seventeenth century, the popularity of such themed sets of images began to wane, and van Everdingen’s devotion to the concept was strikingly unusual. He seems to have made at least eleven sets of drawings of the months, not as one might have imagined, as designs for prints, but as artistic creations in their own right. Six of these sets remain intact, while Davies (see lit.) has reconstructed the others, on the basis of their stylistic and physical characteristics, and clues from the early provenance of the drawings. -

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn – the Storm on the Sea of Galilee

1 Classical Arts Universe - CAU Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn – The Storm on the Sea of Galilee Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, the Dutch painting marvel, always took interest in portraying landscapes, self-portraits and portraits of other artists. His landscape depictions have been never purely about the aesthetics of Nature, but predicted many things about hua life like strife, ager, hope, desire, et. The “tor o the “ea of Galilee or Christ i the Storm on the “ea of Galilee is suh a asterpiee depitig the Bilial see of Jesus and the disciples crossing the sea when there is a raging storm. The painting was completed in the year 1633 and Rembrandt took the maritime theme of the painting to ensure that the theme will be familiar to the people of the age and time. As an effort to establish himself as an artist, he took this subject and it is his only seascape painting. The Storm on the Sea of Galilee depicts the time when the disciples were terrified of the violent storm and are perplexed about their actions. A fierce wave is shown lifting the boat and it is about to engulf the boat into the sea. Christ looks at his disciples and their state of mind from the stern and is about to command the storm to halt. All the distressful renderings in the painting are consoled by a yellow light that is shown to set apart the clouds and create a hope to the members on the boat. The mast shown in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee appears in the form of a Cross, indicating that faith is still there for those who pray the God in times of storming human frailties – be it spiritual or physical. -

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry Wednesday, November 8, 2017 the Exhibition Is Organized by the 4:30 – 7:30 P.M

vermeer and the masters of genre painting national gallery of art october 22, 2017 – january 21, 2018 AMONG THE MOST ENDURING IM AGES of the Dutch Golden Age are genre paintings, or scenes of daily life, from the third quarter of the seventeenth century. Made during a time of unparalleled inno- vation and prosperity, these exquisite portrayals of refined Dutch society — elegant men and women writing letters, playing music, and tending to their daily rituals — present a genteel world that is extraordinarily appealing. Today, Johannes Vermeer is the most cel- ebrated of these painters thanks to the beauty and tranquility of his images. Yet other masters, among them Gerard ter Borch, Gerrit Dou, Frans van Mieris, and Gabriel Metsu, also created works that are remarkably similar in style, subject matter, and technique. The visual connections between these artists’ paintings suggest a robust atmosphere of innovation and exchange — but to what extent did they inspire each other’s work, and to what extent did they follow their own artistic evolution? This exhibition brings together almost seventy paintings made between about 1655 and 1680 to explore these questions and celebrate the inspiration, rivalry, and artistic evolution of Vermeer and other masters of genre painting. Cover Johannes Vermeer Lady Writing (detail), c. 1665 oil on canvas National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Harry Waldron Havemeyer and Horace Havemeyer, Jr., in memory of their father, Horace Havemeyer (cat. 2.3) (opposite) detail fig. 7 Gabriel Metsu Man Writing a Letter Fig. 1 (left) Gerard ter Borch Woman Writing a Letter, c. 1655 – 1656 oil on panel Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague (cat. -

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 13001700 Sheila McTighe Representing from LifeLife inin Seventeenth-century Italy FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Representing from Life in Seventeenth-century Italy FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late me- dieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes monographs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seemingly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the Nation- al Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Wom- en, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Representing from Life in Seventeenth- century Italy Sheila McTighe Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: Claude Lorrain. An artist studying from nature. 1639. Oil on canvas. Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio, USA / Gift of Mary Hanna / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Newgen/Konvertus isbn 978 94 6298 328 1 e-isbn 978 90 4853 326 8 doi 10.5117/ 9789462983281 nur 685 © S.