Nexus Conference 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nexus Conference 2009

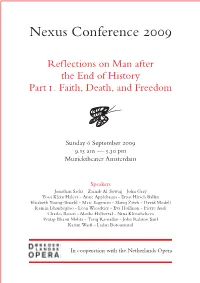

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

Curriculum Vitae Hent De Vries

CURRICULUM VITAE HENT DE VRIES Paulette Goddard Professor of the Humanities Professor of Religious Studies, German, Comparative Literature, and Affiliated Professor of Philosophy New York University Director School of Criticism and Theory Cornell University Russ Family Professor Emeritus in the Humanities Department of Comparative Thought and Literature [formerly The Humanities Center], Department of Philosophy Johns Hopkins University OFFICE ADDRESSES Religious Studies Tel.: 1-212-998-3871 New York University Fax: 1-212-995-4827 726 Broadway, Suite 554 Email: [email protected] New York, NY 10003 https://as.nyu.edu/faculty/hent-de-vries.html School of Criticism and Theory Tel. 607-255-9276 Cornell University Fax. 607-255-1422 A.D. White House Email: [email protected] 27 East Avenue http://sct.cornell.edu/about/directors-welcome/ Ithaca, NY 14863 Department of Comparative Thought Tel.: 1-410-516-7619 and Literature Fax: 1-410-516-4897 Johns Hopkins University Email: [email protected] Gilman Hall 214 http://compthoughtlit.jhu.edu/directory/hent-de- 3400 N. Charles Street vries/ Baltimore, MD 21218 CURRENT ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS July 2017 – present Paulette Goddard Professor of the Humanities. Professor of Religious Studies, German, Comparative Literature, and Affiliated Professor of Philosophy, New York University. June 2014 – July 2022 Director, School of Criticism and Theory (SCT), Cornell University, Ithaca. July 2018 – present Russ Family Professor Emeritus in the Humanities & Philosophy, Department of Comparative Thought and Literature [formerly The Humanities Center] and Department of Philosophy, Johns Hopkins University. PAST ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2017-2018 Titulaire de la Chaire de Métaphysique Etienne Gilson at the Institut Catholique de Paris (ICP). -

BILDERBERG MEETINGS HOTEL DE BILDERBERG OSTERBEEK, NETHERLANDS 29-31 May 1954

BILDERBERG MEETINGS HOTEL DE BILDERBERG OSTERBEEK, NETHERLANDS 29-31 May 1954 PROVISIONAL LIST in alphabetical order PRESIDENT: His Royal Highness, The Prince of The Netherlands. VICE-PRESIDENTS: Coleman, John S. van Zeeland, Paul. SECRETARY GENERAL: Retinger, J. H. RAPPORTEURS: Ball, George W. U.S.A. Lawyer. Bingham, George Barry U.S.A. Newspaper publisher Chief of Mission to France, Economic Cooperation Administration, 1949-1950 Gaitskell, The Rt. Hon. H. T. N. U.K. Member of Parliament, Former Chancellor of the Exchequer de Gasperi, Alcide Italy. Member of Parliament, former Prime Minister Hirschfeld, H. M. Netherlands. Economic Adviser to the Netherlands' Government Former High Commision of the Nethelrands' Government in Indonesia. Director of Companies. Mollet, Guy France. Member of Parliament. Former Deputy Prime Minister. Secretary General of the Socialist Party Nitze, Paul H. U.S.A. President, Foreign Service Educational Foundation. Director, Policy Planning Staff, Dept. of State, 1950-1953. de la Vallee Poussin, Etienne Belgium. Senator Rockefeller, David U.S.A. Banker. Senior Vice-President, The Chase National Bank. Zellerbach, J. D. U.S.A. Industrialist. Member of U.S. Delegation, General Assembly of United Nations, 1953. Chief, ECA Special Mission to Italy, 1948-1950. *** Andre, Robert France. President of the “Syndicat de Petrole”. Assheton, The Rt. Hon. Ralph U.K. Member of Parliament, former Parliamentary Secretary to Ministry of Supply, Former Financial Secretary to the Treasury. De Beaumont, G. France. Member of Parliament Bonvoisin, Pierre Belgium. Banker, President of the “Banque de la Societe Generale de Belgique”. Boothy, Sir Robert U.K. Member of Parliament. Brauer, Max Germany. Former Mayor and President of the Land of Hamburg Cafiero, Raffaele Italy. -

BILDERBERG 2015 63Ème Conférence Bilderberg 11-14 Juin 2015 Telfs-Buchen Autriche

BILDERBERG 2015 63ème conférence Bilderberg 11-14 Juin 2015 Telfs-Buchen Autriche 1 km Littéralement « montagne d’image », le Groupe Bilderberg tient son nom de l’hôtel ayant accueilli la première édition en 1954. Depuis trois ans, je documente les périphéries de ce congrès hermétique. 4 5 Réunion annuelle sur invitation, le Bilderberg héberge officieusement 130 participants provenant principalement du monde occidental. 6 7 Chaque année, un hôtel au décor impénétrable est réservé pour permettre ce rassemblement d’acteurs majeurs du monde politique, monarchique, diplomatique, économique et médiatique. 8 9 Une zone intérdite est définie. Un déploiement massif de forces de sécurité est mis en place à l’intérieur de la propriété privée, débordant également sur les lieux publics. 10 11 Des milliers de policiers, des militaires et d’avions de surveillance oeuvrent à l’opacité de ces rencontres. Aucune conférence de presse à l’agenda ni aucun bilan rendu public. 12 13 Mon intérêt se focalise sur la limite territoriale établie pendant la conférence. Une frontière tantôt floue, tantôt rigoureuse, évoluant jour aprés jour. 14 15 Muni d’une chambre photographique, cantonné sur le sol public, j’ai malgré tout subi onze contrôles de police et trois menaces d’arrestation. 16 17 La prochaine réunion se tiendra quelque part à Dresde, en Allemagne, du 9 au 12 juin 2016. 18 19 Austria: Werner Faymann (2009, 2011, 2012) Chancellor 2008–present; Heinz Fischer (2010, 2015) Federal President 2004–present; Alfred Gusenbauer (2007, 2015) Chancellor national and -

AB-Reframingthediplomat-Cover Copy Voor Digital

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/54855 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Bloemendal, N.A. Title: Reframing the diplomat: Ernst van der Beugel and the Cold War Atlantic Community Issue Date: 2017-09-06 7. The Challenge of the Successor Generation While the preceding chapter already introduced Van der Beugel’s public diplomacy efforts in constructing a sense of Atlantic community by keeping the Atlantic mindset alive in a time of détente and the democratization of foreign policy, this chapter will continue this analysis with a more specific focus on the challenge of the successor generation. After all, diplomacy is not just about short term goals such as negotiating deals and crafting policies. On a more fundamental level, diplomacy is just as much about fostering and maintaining relationships; about ideas, values and identities, about creating an environment and a climate that enables the realization of more concrete and short term goals. Likewise, the challenge of the successor generation was not so much about how to shape European integration or how to legitimize a strong Atlantic defense. Instead it was concerned with the long-term challenge of fostering and maintaining the social fabric and mindset that served as the glue that kept the Atlantic Community together. This shared mindset as well as the social fabric supporting the Atlantic alliance was both maintained and embodied by the Atlantic elite, composed of the constellation of state officials and private individuals and organizations working to foster and maintain close transatlantic ties and who were committed to transmitting this understanding to the public at large.