Cubs Try Hard Enough Vs. Koufax to Make Him Pitch a Game and a Half Twice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Park' to House 1,200 Condos

Ratner gets 45 days to up ante MTA talks exclusively with Bruce despite his low offer By Jess Wisloski ner’s company, with the hopes of upping its the July 27 meeting that neither bid came commitment of her company to the proj- The Brooklyn Papers bid by the board’s Sept. 29 meeting. close enough to the state authority’s $214 ect, and reiterated Extell’s plans to develop Ratner’s bid offers $50 million up front. million appraised value for the rail yards to 1,940 units of new housing, with 573 As it once was, so it shall be again, It also includes $29 million in renovations justify the board’s interest. mixed-income units. the Metropolitan Transportation of the rail yards (to help pay for the reloca- Compared to Ratner’s bid — which was She said the costs of infrastructure and Authority board decided this week, tion of them required by Ratner’s plan), two years in the making and included any required platform would be paid for when it cast aside the high bidder — $20 million in environmental remediation dozens of support letters from elected offi- by Extell, and again raised an offer pre- / Jori Klein who offered $150 million to develop of the land (which needs to be done in or- cials, a myriad of minority contracting or- sented by Extell on Monday to work with the Long Island Rail Road storage der to develop the site for housing), $182 ganizations and numerous labor unions, Forest City Ratner to add an arena that / Jori Klein yards at Atlantic Avenue — and million to build a platform (to build the the Extell bid — hastily prepared to meet would be developed on private property. -

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

JOE MADDON 3Rd Annual • August 13, 2018

JOE MADDON 3rd Annual • August 13, 2018 TM TM BENEFITING RESPECT 90 Foundation Hazleton Integration Project (HIP) Charity MONDAY, AUGUST 13, 2018 TM BRYN MAWR COUNTRY CLUB • LINCOLNWOOD, IL (15 Minutes North of Wrigley Field) TOURNAMENT EVENT JOE MADDON “TRY NOT TO SUCK”TM CELEBRITY GOLF CLASSIC • 2018 AUGUST 13, 2018 | BRYN MAWR COUNTRY CLUB 6600 N. CRAWFORD AVENUE-LINCOLNWOOD IL 12NOON - Shotgun Start! Day-of Schedule 9:00AM – Registration Opens, Step & Repeat, Photos, 11:40AM Continental Breakfast 9:00AM Putting Contest Begins, Live 670-AM The Score Radio Show 11:45AM Call to Carts 12NOON Shotgun Start (Lunch on Course) 4:00PM Awards Reception and Entertainment, Live Auction Jerry Lasky 312 502 8300 Steve DiMarco 818 594-7277 TM [email protected] Golf On Earth Event Services [email protected] TM SPONSORSHIP TOURNAMENT TITLE SPONSOR - $75,000 AWARDS RECEPTION SPONSOR - $5,000 • Two teams of four players plus choice of celebrity players* • Prominent Sponsor recognition on signage at Awards Reception • Prominent Title Sponsor recognition on official event materials • Prominent Sponsor recognition on official event sponsor banner (Including sponsor banner, brochure, etc.) • Reserved seating at awards reception after golf • Brand logo recognition on all tee signs • Awards Reception Sponsor recognition in tournament press • Title Sponsor recognition and signage at awards reception release and media-related opportunities • Title Sponsor recognition in tournament press release and all • Awards reception tickets (4) following play -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Page One Layout 1

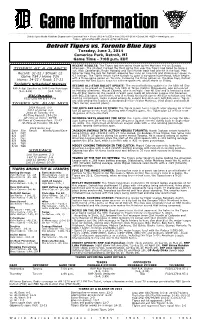

Game Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Detroit Tigers Media Relations Department w Comerica Park w Phone (313) 471-2000 w Fax (313) 471-2138 w Detroit, MI 48201 w www.tigers.com Twitter - @DetroitTigersPR, @tigers, @TigresdeDetroit Detroit Tigers vs. Toronto Blue Jays Tuesday, June 3, 2014 Comerica Park, Detroit, MI Game Time - 7:08 p.m. EDT RECENT RESULTS: The Tigers lost the series finale to the Mariners 4-0 on Sunday TIGERS AT A GLANCE afternoon. The shutout marked the third game this year the Tigers had failed to score a run. Nick Castellanos, Bryan Holaday and Torii Hunter each had one hit in the loss. Max Record: 31-22 / Streak: L2 Scherzer took the loss for Detroit, allowing four runs on nine hits and striking out seven in Game #54 / Home #26 6.2 innings. The Tigers return home tonight to open a six-game homestand, which begins with a three-game series vs. Toronto. Following the three games vs. the Blue Jays, Detroit Home: 14-11 / Road: 17-11 welcomes the Red Sox to town for a three-game set, which starts on Friday. Tonight’s Scheduled Starters SECOND ALL-STAR BALLOT UPDATE: The second balloting update for the 85th All-Star RHP Anibal Sanchez vs. RHP Drew Hutchison Game, to be played on Tuesday, July 15th at Target Field in Minneapolis, was announced (2-2, 2.49) (4-3, 3.88) on Monday afternoon. Miguel Cabrera, who is an eight-time All-Star and is looking to start the All-Star Game for the second straight year, leads all American League first basemen TV/Radio with 962,138 votes. -

Baseball Autographs Signed 1950-55 Callahans 297 Honus Wagner 9

January 31 Auction: Baseball Autographs Signed 1950-55 Callahans 297 Honus Wagner 9 ............................ 500 Such a neat item, offered is a true high grade hand-signed 290 Fred Clarke 9.5 ......................... 100 Honus Wagner baseball card. So hard to find, we hardly ever Sharp card, this looks to be a fine Near Mint. Signed in par- see any kind of card signed by the legendary and beloved ticularly bold blue ink, this is a terrific autograph. Desirable Wagner. The offered card, slabbed by PSA/DNA, is well signed card, deadball era HOFer Fred Clarke died in 1960. centered with four sharp corners. Signed right in the center PSA/DNA slabbed. in blue fountain pen, this is a very nice signature. Key piece, this is another item that might appreciate rapidly in the 291 Clark Griffith 9 ............................ 150 future given current market conditions. Very scarce signed card, Clark Griffith died in 1955, giving him only a fairly short window to sign one of these. Sharp 298 Ed Walsh 9 ............................ 100 card is well centered and Near Mint or better to our eyes, Desirable signed card, this White Sox HOF pitcher from the this has a fine and clean blue ballpoint ink signature on the deadball era died in 1959. Signed neatly in blue ballpoint left side. PSA/DNA slabbed. ink in a good spot, this is a very nice signature. Slabbed Authentic by PSA/DNA, this is a quality signed card. 292 Rogers Hornsby 9.5 ......................... 300 Remarkable signed card, the card itself is Near Mint and 299 Lot of 3 w/Sisler 9 ..............................70 quite sharp, the autograph is almost stunningly nice. -

The Last Innocents: the Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers Online

rck87 (Get free) The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers Online [rck87.ebook] The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers Pdf Free Michael Leahy ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook #120314 in Books Michael Leahy 2016-05-10 2016-05-10Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x 1.49 x 6.00l, .0 #File Name: 0062360566496 pagesThe Last Innocents The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers | File size: 71.Mb Michael Leahy : The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers: 29 of 31 people found the following review helpful. SHAQ GOLDSTEIN SAYS: 1960rsquo;S DODGERShellip; UNDER THE MICROSCOPE.. ONhellip; hellip; OFF THE FIELD. A GROWN UP KID OF THE 60rsquo;S DREAM COME TRUEBy Rick Shaq GoldsteinAs a child born in New York to a family that lived and died with the Brooklyn Dodgershellip; ldquo;Dem Bumsrdquo; were my lifehellip; and lo and behold when the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles after the 1957 seasonhellip; my family moved right along with them. So the time period covered in this amazinghellip; detailedhellip; no holds barredhellip; story of the 1960rsquo;s era Los Angeles Dodgershellip; is now being read and reviewed by a Grandfatherhellip; who as a kidhellip; not only went to at least one-hundred games at the L.A. -

Dflflflb SHOP TONIGHT to 9

•• THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. Friday. September C-4 ——— a. issv MAJOR LEAGUE BOX SCORES Braves' Pitching Gives fowler Denies CARDS, 10; BRAVES, 1 PIRAfES, 4; GIANTS, 2 DODGERS, 3; PHILUES, 1 Cardinals New Hope Quit NewYark A.H.O.A. P’abarib A.iXJA. Brook Ira A.H.O.A. Phils. AJi.O.A. Continued From Fsge C-l Don Hoak’a two-run double Plans to Clmoll.cf 4 (I * u Ashb'rn.cf 3 2 19 Torre.lb 4 1 13 O Derk.te 6 10 4 Mueßertrl fits VtoS&'cf !8 8 Reese.lib 4 II 0 3 Repuakl.rl 4 9 4 0 and Del Ennis accounted for In the second and Prank Robin- Sept 0 SPARTANBURG, S. C.. Valo.ll 3 0 8 B'chce.lb 4 16 1 two runs with his 19th homer son's 24th home run in the sSys lAnsor‘s.U 9 0 10 Lopatt.c 4 18 0 6 (fl.—Pitcher Art Fowler, sold ?}»sssef m Hodtea.lb 4 1 119 481mmons O o o 9 in the sixth. Then the Cards > third gave Brooks Lawrence ssasir" i 11J 8 »i Furlllo.rf 4 3 8 0 And'aon.U 4 o 1 9 bagged five in the eighth- all he needed for his 14th vic- by Cincinnati to Seattle of the ? 8 ? S La’Srith.r ¦: ? Neal.as il 14 Ha'ner.2b 4 12 3 2 f pitiP0 Douilaa.p 0 0 0 Walker.e 4 14 0 Kas’tkl.3b 4 1 4 0 three on A1 Dark’s pop fly tory although the Redlegs were League, denied W'xton.D 110 4 Pacific Coast ljthodaa inn o paca.p 0 0 0 u Zlm er.2b 3 0 3 2 Per'det.ss 3 0 11 out bit, Dick assss-'sss10 i IK t SS3 M’aant.p 0 0 0 0 Braklne.p 3 0 0 1 Roberts.p 2 0 12 double—for a 13-hit total I 7-6. -

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist 1 Hoyt Wilhelm 2 Alvin Dark 3 Joe Coleman 4 Eddie Waitkus 5 Jim Robertson 6 Pete Suder 7 Gene Baker 8 Warren Hacker 9 Gil McDougald 10 Phil Rizzuto 11 Bill Bruton 12 Andy Pafko 13 Clyde Vollmer 14 Gus Keriazakos 15 Frank Sullivan 16 Jimmy Piersall 17 Del Ennis 18 Stan Lopata 19 Bobby Avila 20 Al Smith 21 Don Hoak 22 Roy Campanella 23 Al Kaline 24 Al Aber 25 Minnie Minoso 26 Virgil Trucks 27 Preston Ward 28 Dick Cole 29 Red Schoendienst 30 Bill Sarni 31 Johnny TemRookie Card 32 Wally Post 33 Nellie Fox 34 Clint Courtney 35 Bill Tuttle 36 Wayne Belardi 37 Pee Wee Reese 38 Early Wynn 39 Bob Darnell 40 Vic Wertz 41 Mel Clark 42 Bob Greenwood 43 Bob Buhl Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Danny O'Connell 45 Tom Umphlett 46 Mickey Vernon 47 Sammy White 48 (a) Milt BollingFrank Bolling on Back 48 (b) Milt BollingMilt Bolling on Back 49 Jim Greengrass 50 Hobie Landrith 51 El Tappe Elvin Tappe on Card 52 Hal Rice 53 Alex Kellner 54 Don Bollweg 55 Cal Abrams 56 Billy Cox 57 Bob Friend 58 Frank Thomas 59 Whitey Ford 60 Enos Slaughter 61 Paul LaPalme 62 Royce Lint 63 Irv Noren 64 Curt Simmons 65 Don ZimmeRookie Card 66 George Shuba 67 Don Larsen 68 Elston HowRookie Card 69 Billy Hunter 70 Lew Burdette 71 Dave Jolly 72 Chet Nichols 73 Eddie Yost 74 Jerry Snyder 75 Brooks LawRookie Card 76 Tom Poholsky 77 Jim McDonald 78 Gil Coan 79 Willy MiranWillie Miranda on Card 80 Lou Limmer 81 Bobby Morgan 82 Lee Walls 83 Max Surkont 84 George Freese 85 Cass Michaels 86 Ted Gray 87 Randy Jackson 88 Steve Bilko 89 Lou -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #92 VINTAGE HALL OF FAMERS ROOKIE CARDS SALE – TAKE 10% OFF 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron 1959 Topps #338 Sparky 1956 Topps #292 Luis Aparicio 1954 Topps #94 Ernie Banks EX- 1968 Topps #247 Johnny Bench EX o/c $550.00 Anderson EX $30.00 EX-MT $115.00; VG-EX $59.00; MT $1100.00; EX+ $585.00; PSA PSA 6 EX-MT $120.00; EX-MT GD-VG $35.00 5 EX $550.00; VG-EX $395.00; VG $115.00; EX o/c $49.00 $290.00 1909 E90-1 American Caramel 1909 E95 Philadelphia Caramel 1887 Tobin Lithographs Dan 1949 Bowman #84 Roy 1967 Topps #568 Rod Carew NR- Chief Bender PSA 2 GD $325.00 Chief Bender FR $99.00 Brouthers SGC Authentic $295.00 Campanella VG-EX/EX $375.00 MT $320.00; EX-MT $295.00 1958 Topps #343 Orlando Cepeda 1909 E92 Dockman & Sons Frank 1909 E90-1 American Caramel 1910 E93 Standard Caramel 1909 E90-1 American Caramel PSA 5 EX $55.00 Chance SGC 30 GD $395.00 Frank Chance FR-GD $95.00 Eddie Collins GD-VG Sam Crawford GD $150.00 (paper loss back) $175.00 1932 U.S. Caramel #7 Joe Cronin 1933 Goudey #23 Kiki Cuyler 1933 Goudey #19 Bill Dickey 1939 Play Ball #26 Joe DiMaggio 1957 Topps #18 Don Drysdale SGC 50 VG-EX $375.00 GD-VG $49.00 VG $150.00 EX $695.00; PSA 3.5 VG+ $495.00 NR-MT $220.00; PSA 6 EX-MT $210.00; EX-MT $195.00; EX $120.00; VG-EX $95.00 1910 T3 Turkey Red Cabinet #16 1910 E93 Standard Caramel 1909-11 T206 (Polar Bear) 1948 Bowman #5 Bob Feller EX 1972 Topps #79 Carlton Fisk EX Johnny Evers VG $575.00 Johnny Evers FR-GD $99.00 Johnny Evers SGC 45 VG+ $170.00; VG $75.00 $19.95; VG-EX $14.95 $240.00 KIT YOUNG CARDS • 4876 SANTA MONICA AVE, #137 • DEPT. -

MTA Report June 2009

Metro Report: Home CEO Hotline Viewpoint Classified Ads Archives Metro.net (web) Resources Safety Pressroom (web) Check it out at www.dodgers.com Ask the CEO Leahy's on the mound. Here's the wind-up and the pitch. CEO Forum It's Metro Night at Dodger Stadium Aug. 8 Employee Recognition $25 includes admission and all you can eat! Tickets will be on sale through July 31 at the Employee Activities credit union’s Metro Headquarters office, the Gardena location, and from Metro transportation stenos at the following divisions: 1, 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 21 and at Rail Metro Projects Operation Control (ROC). Facts at a Glance By Laura Kloth (web) Staff Writer Archives Warming up in the improvised bull pen behind the Metro Gateway Center, CEO Art Leahy loosens up in preparation for what will prove to be the most Events Calendar memorable of his many baseball memories – the chance to stand on the Research Center/ mound at Dodger Stadium and throw the first pitch at the upcoming Metro Library Night Game, Aug. 8. Metro Classifieds Bazaar Metro Info The artful Dodger? 30/10 Initiative Metro's CEO plays hardball, Aug. 8, when Policies he takes the mound to throw out the first Training pitch at Dodger Stadium in the home Help Desk game against the Atlanta Braves. Intranet Policy Need e-Help? Stock photo video image. Call the Help Desk at 2-4357 Contact myMetro.net OK, we’re just kidding about the bullpen behind the Metro headquarters, but not about Leahy’s memories of watching some of the greatest players who ever judiciously pine-tarred the grip of a finely-crafted Louisville Slugger. -

Awards Victory Dinner

West Virginia Sports Writers Association Victory Officers Executive committee Member publications Wheeling Intelligencer Beckley Register-Herald Awards Bluefield Daily Telegraph Spirit of Jefferson (Charles Town) Pendleton Times (Franklin) Mineral Daily News (Keyser) Logan Banner Dinner Coal Valley News (Madison) Parsons Advocate 74th 4 p.m., Sunday, May 23, 2021 Embassy Suites, Charleston Independent Herald (Pineville) Hampshire Review (Romney) Buckhannon Record-Delta Charleston Gazette-Mail Exponent Telegram (Clarksburg) Michael Minnich Tyler Jackson Rick Kozlowski Grant Traylor Connect Bridgeport West Virginia Sports Hall of Fame President 1st Vice-President Doddridge Independent (West Union) The Inter-Mountain (Elkins) Fairmont Times West Virginian Grafton Mountain Statesman Class of 2020 Huntington Herald-Dispatch Jackson Herald (Ripley) Martinsburg Journal MetroNews Moorefield Examiner Morgantown Dominion Post Parkersburg News and Sentinel Point Pleasant Register Tyler Star News (Sistersville) Spencer Times Record Wally’s and Wimpy’s Weirton Daily Times Jim Workman Doug Huff Gary Fauber Joe Albright Wetzel Chronicle (New Martinsville) 2nd Vice-President Secretary-Treasurer Williamson Daily News West Virginia Sports Hall of Fame Digital plaques with biographies of inductees can be found at WVSWA.org 2020 — Mike Barber, Monte Cater 1979 — Michael Barrett, Herbert Hugh Bosely, Charles L. 2019 — Randy Moss, Chris Smith Chuck” Howley, Robert Jeter, Howard “Toddy” Loudin, Arthur 2018 — Calvin “Cal” Bailey, Roy Michael Newell Smith, Rod